Thomas Elsaesser & Malte Hagener's "Cinema as Door" in Film Theory

Intro & Overview: So far this semester:

- we began with Kant’s Critique of Judgment to learn the classic model of making Judgments of the Beautiful and Sublime, which were supported with reading Clive Bell on Significant Form and Jean-François Lyotard on the Modern and Postmodern Sublime and Kazimir Malevich’s sublime-like Suprematism;

- we then looked into the roles Emotions play in art judgment through R. G. Collingwood, Leo Tolstoy, and Lev Vygotsky;

- from emotions, we turned to Embodied Art Theories in Stephen Pepper and Edward Bullough’s analyses of nearness and farness in art evaluation;

- next, we read a many-sided interpretative approach in Michel Foucault’s Post-Structuralist Archeological Analysis of Veláquez’s “Las Meninas” …

Now … this reading—Thomas Elsaesser & Malte Hagener’s “Cinema as Door: Screen and Threshold”—takes our focus to a new medium—film, over the majority of prior readings focusing more so on visual arts, esp. painting—but connects well with our earlier themes. Elsaesser & Hagener incorporate a post-structuralist analysis (like Lyotard and Foucault), address matters of form (Kant and Bell), emotions (Collingwood, Tolstoy, Vygotsky), and embodied experience (Pepper and Bullough), but, overall, are approaching the interpretation of film (film-itself and films) most akin to Foucault: using many diverse approaches, and letting their findings speak as much to the social factors from which film comes as they do to the specific films they discuss.

Exploring and working from interconnected topics of The Door and Screen, thus also Liminal Spaces demarcated as Thresholds and Frontiers, Elsaesser & Hagener highlight these themes at work in specific films (especially John Ford’s 1956 “The Searchers”) to open up what these symbols say about film itself and demonstrate a new many-faceted method of film interpretation and aesthetical evaluation.

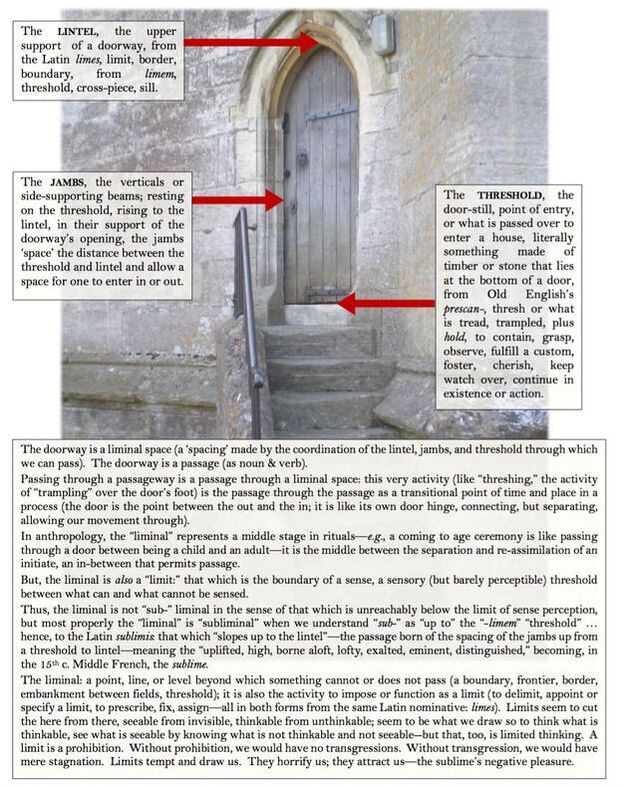

Before notes on our reading "Cinema as Door: Screen and Threshold," I offer a cross-disciplinarily annotated image of a door to provoke paths for thinking more deeply about doors in relation to aesthetics most generally ... :

... now ...

Thomas Elsaesser & Malte Hagener’s “Cinema as Door: Screen and Threshold,” 35-54,

in Film Theory: An Introduction Through the Senses (pdf on Blackboard)

Thomas Elsaesser & Malte Hagener’s “Cinema as Door: Screen and Threshold,” 35-54,

in Film Theory: An Introduction Through the Senses (pdf on Blackboard)

Film Still, John Ford's "The Searchers," 1956

Film Still, John Ford's "The Searchers," 1956

This chapter opens with two (paired) descriptions of scenes within John Ford’s 1956 film “The Searchers”*: from its opening, a woman exiting through a door, which opened to reveal Monument Valley, and a man leaving the wild to enter into a settler’s cabin; then, from its close, this man leaves the cabin to walk out and off into the wild west’s sunset. In between the authors’ description of these scenes, they reveal: “The film is constructed around a series of crossings and transgressions, and it involves a constant change of places, both literally and metaphorically: it oscillates between familial and racial affiliation, between nature and culture, between wilderness and garden, between convictions and actions” (p.35). And here we have our theme—for this chapter, for this week—introduced: the door, moreover, the threshold: “the passage from one world to another which presupposes the co-existence of two worlds, separated as well as connected by the threshold” (pp.35-36).

* For more information on "The Searchers," see: IMDB description; or Wikipedia description; or Door-Way clip video; or Rotten Tomatoes Review; or Roger Ebert Review.

* For more information on "The Searchers," see: IMDB description; or Wikipedia description; or Door-Way clip video; or Rotten Tomatoes Review; or Roger Ebert Review.

The threshold’s literal and symbolic meanings operate on three levels:

- The Spectator: “the threshold between her/his world and that of the film” (36);

- The Film: “the threshold between myth and reality” (36);

- The Actor: “the threshold between role and image” (36).

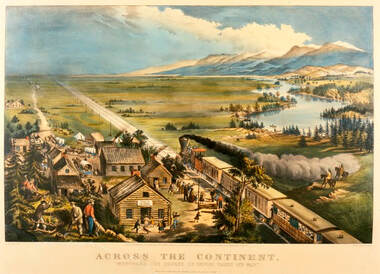

The Frontier: “that borderline between ‘civilized land’ and ‘the wilderness’. … This story of conquering and subjecting the vast expanses of land … the United States fashioned … its own myth of self-creation” (36).

“In film, this myth is based upon an underlying binary opposition of nature/culture: the garden versus the wilderness, cowboys versus Indians, but also cattle barons versus homesteaders …, the law of the gun versus the law of the book, the saloon singer versus the teacher, etc.. The Western constantly stages and affirms the frontier as a demarcation and its (necessary) transgression as the basis of US popular culture as the nation’s mythology” (36).*

“In film, this myth is based upon an underlying binary opposition of nature/culture: the garden versus the wilderness, cowboys versus Indians, but also cattle barons versus homesteaders …, the law of the gun versus the law of the book, the saloon singer versus the teacher, etc.. The Western constantly stages and affirms the frontier as a demarcation and its (necessary) transgression as the basis of US popular culture as the nation’s mythology” (36).*

-

- * ... Just to play devil’s advocate—countering this interpretation as much as those we saw in Collingwood and Tolstoy as they argued for art as a communication of emotion—we can also propose a more Kantian inspired idea of the beautiful as radically opposed to anything cognitive, or, as the contemporary philosopher Etienne Gilson reminds us in his The Arts of the Beautiful, it is a mistake to speak of art as if it were an act of communication, rather than an act of production**, or, of Georges Bataille, who declares “It is vain to consider, in the appearance of things, only the intelligible signs that allow the various elements to be distinguished from each other. What strikes human eyes determines not only the knowledge of the relations between various objects, but also a given decisive and inexplicable state of mind”***, that film is not just telling us the myth as a series of logical contraries, but that it shows us something that gets us to feel, from, with, and through it, something disjointing and conflicting, that film’s landscapes communicate, not through subtexts of concepts intended by their designers, but through an imbued mood generated by a dialogical communion with their viewers.

- ** Etienne Gilson, The Arts of the Beautiful (Champaign, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 2000), pp. 9-16.

- *** Georges Bataille, “Le langagae des Fleurs,” Documents 1 (1929), reprinted as “The Language of Flowers,” trans. Allan Stoekl, in Karl Blossfeldt, Art Forms in Nature (Munich: Schirmer Art Books, 1999), pp. 7-11, p. 7.

- * ... Just to play devil’s advocate—countering this interpretation as much as those we saw in Collingwood and Tolstoy as they argued for art as a communication of emotion—we can also propose a more Kantian inspired idea of the beautiful as radically opposed to anything cognitive, or, as the contemporary philosopher Etienne Gilson reminds us in his The Arts of the Beautiful, it is a mistake to speak of art as if it were an act of communication, rather than an act of production**, or, of Georges Bataille, who declares “It is vain to consider, in the appearance of things, only the intelligible signs that allow the various elements to be distinguished from each other. What strikes human eyes determines not only the knowledge of the relations between various objects, but also a given decisive and inexplicable state of mind”***, that film is not just telling us the myth as a series of logical contraries, but that it shows us something that gets us to feel, from, with, and through it, something disjointing and conflicting, that film’s landscapes communicate, not through subtexts of concepts intended by their designers, but through an imbued mood generated by a dialogical communion with their viewers.

The Chapter’s Outline:

this chapter, "Cinema as Door" ... “deals with the different ways the spectator enters into this world, physically as well as metaphorically” … themes of separation and thresholds between the film world and the real world on spatial, architectural, institutional, economic, and textual levels:

- (a) introductory remarks: cinema’s real and imaginary thresholds;

- (b) etymology;

- (c) narratology (re: spectator’s entry to films):

- –i.e., Narratology is a form of criticism and practice that analyzes narrative structure and function (how is it, what does it do); its quest is for the best schema to characterize how the said and its saying effectuate meaning. In postmodernism, “grand narratives” (e.g., “power to the people,” “land of milk and honey,” “bootstrappers,” “love thy neighbor,” “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” etc.) are the result of our very natural attempts to make complexity make sense, but these then become the structural biases guiding all interpretation, knowledge, and life—when we use these narratives, we use and inherit an entire logic, and become an element within a world of meaning given us, unquestionably accepted—thus they need our close examination. Thus, the schemata are incessantly marked up and annotated, effectively revealing conceptual margins full of question marks because a question never ends a quest—it perpetuates it: every mark revivifies the marginalia of human history like incessant insertions of ellipses so that postmodernism’s study of narrative is, at heart, a questing as questioning of the presence of the past’s future and reveals our experience of a problem of meaning, a problem from the simultaneity of incommensurate ‘truths’ (e.g., consider the narrative tropes about “woman” emblematized in her simultaneous archetypal depictions as virgin, mother, and whore)—to see a call for narratological critique, recall Foucault’s preface’s revelation of the in-between opened up when we realize the distinction between codes of conduct and meta-analyses of these codes (see ~here~ for Foucault pages)).

- –via neoformalist interpretation;

- –i.e., an approach to film theory that posits art’s purpose to be our ‘defamiliarization’ and therefore regard the analysis of film as necessarily centering on the distinction between the content of a story and the story’s form, and insights that come from such distinction.

- –via post-structuralist interpretation;

- –i.e., Under the broadest umbrella of “Postmodernism,” Post-Structuralism can variously designate a singular school of thought or a diversity of schools that simply come after, born and as critiques of the cross-disciplinary Structuralism, as well as being a set of principles and/or methodologies from diverse fields merged into a solidified system; key principles include: (a) Meaning is structured, created by and creates selves and our involvement in language/society; (b) Meaning structure is also a structure of power; (c) Structures create and therefore impact all levels of knowledge, society, existence; and (d) Understanding requires analyzing relationships between beings, world, and practices of making and reproducing meanings. See ~here~ for more on Post-Structuralism.

(a) Introductory Remarks: Cinema’s Real and Imaginary Thresholds (pp.37-42):

Threshold –connects & separates– –is a borderline, hence comes to be from observation, by identification of a limit (that between a this & a that, a here & a there)– –because a threshold is this limit, the line of connection & separation, every threshold hence points in two directions– –for film, we ask: where is this limit?, where does the threshold of film lie?, where does it begin, end?–

If we conceive of cinema as entry into another world … we, spectators, find ourselves between two poles:

- Projection: pointing outward; permitted the plunge into the film, the personal disintegration (bodily and identity) into the communal experience, which is also a self-alienating objectification;

- Identification: pointing inward; permitted to absorb the film into the self, make it one’s own, incorporate it, create oneself within it as an imaginary subject.

E.g.: Edgar Morin’s The Cinema & The Imaginary Man:

- Theorizing on our “… polymorphous oscillation between these two positions [projection & identification]” (37-38) … proposing the screen characters function as our Doppelgängers …:

|

Morin proposes this Doppelgänger function is double:

- – Confers on the characters status of projection interface through which we can enter into the film; and

- – Gives characters an uncanny quality, at once embodying the “all-too-familiar” & the “all-too-feared” in ourselves (38).

- The “uncanny”: unheimlich, literally the feeling of being-not-at-home, the “eerie,” “strange,” the “uncanny” (opposite is the German word heimlich, literally the feeling of being-at-home, the “familiar, tame, dear and intimate, homely”—yet, heimlich also has a second meaning that is identical to unheimlich, so the home-ly is as once also the “all-too-familiar” of that which is uncanny).

- Freud’s book, The Uncanny, indicates how this word for homeliness also means its opposite through his dictionary’s quotation “Wir nennen das Unheimlich; Sie nennen’s heimlich”—which says that the feeling of being-at-home is what we call the unhomely and uncanny and what you call the homely and familiar (129).

- Therefore, the uncanny is the eerie feeling of the familiar made strange; its opposite is the feeling of comfortable familiarity; however, just like how night and day are opposites, yet the day’s 24 hours includes the night, the comfy-feeling-at-home also bears within itself its opposite, the uncanny.

- The “uncanny”: unheimlich, literally the feeling of being-not-at-home, the “eerie,” “strange,” the “uncanny” (opposite is the German word heimlich, literally the feeling of being-at-home, the “familiar, tame, dear and intimate, homely”—yet, heimlich also has a second meaning that is identical to unheimlich, so the home-ly is as once also the “all-too-familiar” of that which is uncanny).

Morin’s insights—as well as all the positions described in this reading—“try to conceptualize a liminal situation, a not-quite-here but also a not-quite-there configuration, an in-betweenness of sorts in which film functions as a threshold and space of passage, … a ‘liminal space’” (38).

- The liminal, from the Latin limes, limit, border, boundary, from limem, threshold, cross-piece, sill (cf. annotated picture of the door at the top of these notes!) gives us our word “lintel” (the top of the door’s frame), but that word also designates the threshold (the bottom of the door’s passage way) and the whole conjunction of door jambs (the sides of a door’s frame) spacing out a place for passage between the upper and lower door-structures.

- Hence, the doorway is a liminal space (a ‘spacing’ made by the coordination of the lintel, jambs, and threshold through which we can pass)—it is a passage (as noun & verb: it is a point of in-between that demarcates (before/after, out/in), and that which permits passage, this passing through as activity of passage through the passage); it is also a limit (a boundary of sense, a sensory threshold between what can and cannot be sensed), and therefore the liminal is the sub- (“up to”) -liminal (“threshold”): the sublimis (“that which slopes up to the lintel,” the “borne aloft,” the “exalted, eminent”), the sublime: that affective experience of that which is un-cognizable that attracts and repels us, vehemently draws us into the recognition of that which is beyond comprehension.

(b) etymology (pp.38-39):

Next … from the theoretical broaching of the liminal … we move into the “real interface in the auditorium, the material border between spectator and film, … the screen” (38).

|

|

|

Crossing Borders:

Authors will return to “the screen” as semi-permeable membrane later (pp.53-54) … but want to add that crossing borders can be beyond the material/physical boundaries … the semantic and symbolic border-crossings can concern (39):

- Economic Exchange

- Social Institutions

- Cultural Phenomena

The significance of each of these can vary depending upon our interpretative frame.

They will begin with the most material and physical: Cinema as Material-Immaterial Architectural Ensemble (39ff):

- Façade

- Lobby

- Before the velvet curtained screen

- After the sound of the gong (announcing a film’s start)

- Through advertisements and trailers for coming attractions

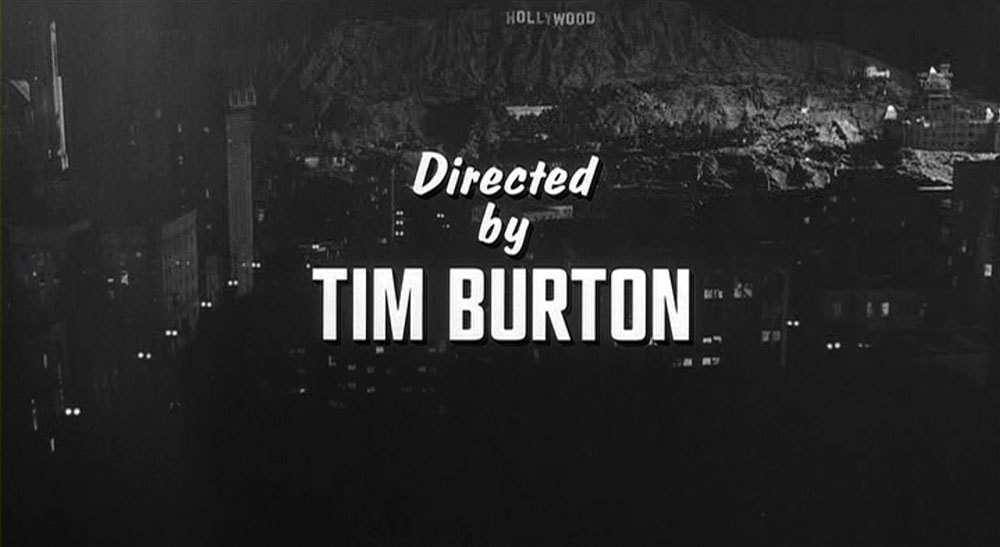

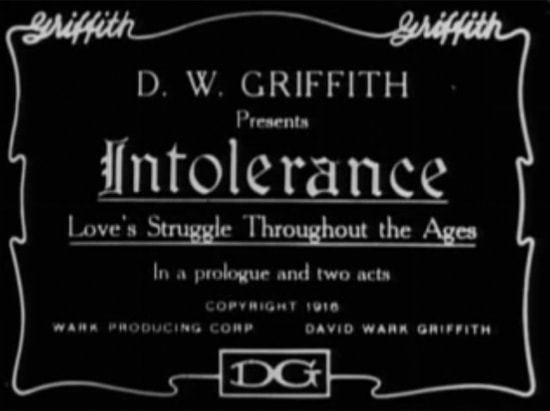

Moreover, there is the entry into, the ‘beginning’, the ‘opening’ of a film as:

- Title

- Announces Origin (book, comic, game, history, etc.)

- Or previews Genre (action, suspense, sex, etc.)

- Poster

- With its ‘tag-line’

- Trailer

- Mini-film of the film

- Opening Materials:

- Logo of distribution/production companies

- Credit sequences

- Title sequence

(c) Narratology (pp.41 ff.):

The authors begin the narratological analysis of film as door with reference to Gerard Genette’s theorizing on “paratexts:”

- Paratext: the fact of and ways that “texts … surround another text, attach themselves to it, occupy it in a parasitical way but also help and support it …” (41) … these paratexts “position themselves between inside (text) and outside (non-text) and create a space of transition and transaction” (41).

- Consider any literary work, a text … a “text rarely appears in its naked state, without the reinforcement and accompaniment of a certain number of productions, themselves verbal or not, like an author’s name, a title, a preface, illustrations. … [these] surround it and they prolong it, precisely in order to present it. … to make it present, to assure its presence in the world, its ‘reception’ and its consumption …”—all this is “the paratext of the work. Thus the paratext is for us the means by which a texts makes a book of itself and proposes itself as such to its readers, and more generally to the public. Rather than with a limit or a sealed frontier, we are dealing in this case with a threshold, or—the term Borges used about a preface—with a ‘vestibule’ which offers to anyone and everyone the possibility either of entering or of turning back. ‘An undecided zone’ between the inside and the outside, itself without rigorous limits. … a zone not just of transition, but of transaction …” (Gérard Genette, “Introduction to the Paratext,” trans. Marie Maclean, New Literary History 22.2 (sp. 1991): 261-72, 261).

- “Paratexts thus indicate the semantic instability and tectonic shifts and turbulence of texts, as inside and outside are never quite stable and fixed and their boundaries become fuzzy or jagged” (42).

- e.g.: “The Rocky Horror Picture Show” (dir. Jim Sherman, 1975)—limited success parody film becoming cult classic due to audience enthusiasm and ‘participation’ (becoming a very genre: the midnight movie).

- “Paratexts, therefore, mediate between the actual text and what lies outside it (its audience, other texts, institutions); they also mark the threshold--i.e., the point of entrance and exit—and forge a ‘communicative contract’ between spectator and text as described by semio-pragmatics” (42).

- Similar to this activity and ‘threshold situation’ realm of analysis opened by and possible through paratexts, we can analyze the opening of filmic narration … specifically, our analysis of such is via narratology.

Thus, narratology … Narratology is a form of criticism and practice that analyzes narrative structure and function (how is it?, what does it do?); it “investigates, theorizes and systematizes the mechanisms and dynamics of film narration” (42) …

- “Film beginnings play a key role … because it is at this point in any film that several functions overlap” a film’s beginning must lure the audience, i.e., it must prompt the necessary attention and suspense, it must plant information, but also set the tone and atmosphere that prepares for the film to come” (42).

- They must: stake out the film’s goal; map its playing field.

Narratology’s two main divides: the Neo-Formalist (cognitive) school and the Post-Structuralist school:

- Neo-Formalist (cognitive): “tend to emphasize rational-choice scenarios and logical information processing” (43); “believes in a fair and free relationship between spectator and text” (43);

- Post-Structuralist: “focus on the instability of meaning” (43); “more interested in power structures and unconscious processes” (43).

Neo-Formalist Narratology (pp.43-45):

- “For neoformalists, a film consists mainly of audio-visual ‘cues’, which the spectator perceives and processes accordingly: ‘… viewers are not passive ‘subjects’. … [but] active, contributing substantially to the final effect of the work’” (43).

- Spectator’s active construction of experienced film: Cues (raw material from plot) lead to hypotheses and schemata, using previous experience/knowledge; mental presuppositions help comprehension of the film’s narrative (film’s story, fabula).

- “Plot”: “the structured set of all causal events as we see and hear them presented in the film itself, i.e. the succession of actions … characterized be spatial and temporal ellipses (cut from a character to another …) … by temporal rearrangements (flashbacks and flashforwards) … and by material or information not belonging to the diegetic world (credits, … music)” (43).

- “… the creation of a causal, temporal and spatial coherence, produces the story” (43).

- e.g.: “Pulp Fiction” (dir. Quentin Tarantino, 1994) plot a-chronologically tells story; “Memento” (dir. Christopher Nolen, 1999) plot is narrated backward to create story.

- Spectator’s active construction of experienced film: Cues (raw material from plot) lead to hypotheses and schemata, using previous experience/knowledge; mental presuppositions help comprehension of the film’s narrative (film’s story, fabula).

- Neo-Formalists on film Openings: “… they create a set of expectations that the film will be measured against by the spectator” (44).

- In media res: in to the middle; without preamble

- E.g.: “The Searchers” (dir. John Ford, 1956) … what does its beginning impart; what expectations does it call forth?:

- A conflict between two brothers (homesteading Aaron & wandering Ethan, who hates Native Americans); such conflict plays out in relations to first brother’s wife (Martha—secretly loved by second brother) and stepson (Martin—wishes to settle down like father): from the film’s beginning, giving this info, double plot lines are established that guide the rest: (a) kidnapping of Aaron’s younger daughter (Debbie) by Native Americans; (b) love story between Martin and Laurie. Both converge in Ethan, via his hate of Native Americans: (b2) rejects Martin as ‘half-breed’; (a2) rejects Debbie as ‘turned Indian’.

- Double Plot Lines: feature of ‘classic films’—typically, one is a task to be accomplished, the other is a love story; they begin as separate, become intertwined; closure comes when both are resolved, one by means of the other (44).

- Neo-Formalist Narratology: a film is “classic” when analysis allows one to understand spectator’s activity of comprehending film is as following the cues, clues, laid out for him/her: “a film functions like an algorithm” (44).

- A conflict between two brothers (homesteading Aaron & wandering Ethan, who hates Native Americans); such conflict plays out in relations to first brother’s wife (Martha—secretly loved by second brother) and stepson (Martin—wishes to settle down like father): from the film’s beginning, giving this info, double plot lines are established that guide the rest: (a) kidnapping of Aaron’s younger daughter (Debbie) by Native Americans; (b) love story between Martin and Laurie. Both converge in Ethan, via his hate of Native Americans: (b2) rejects Martin as ‘half-breed’; (a2) rejects Debbie as ‘turned Indian’.

- Neo-Formalist Narratology has developed in varying types, e.g. Edward Branigan’s development (from Gerard Genette’s ‘focalization’) of a model of seven levels of narration—key here is that from the neoformalist focus on comprehension, it expands focus to emotional entanglement (45).

Post-Structuralist Narratology (pp.45-49):

- Post-Structuralist narratology begins from the structuralist premise that “language and its logic play a constitutive role for cultural processes of any kind, including narrative, whose logics are based on the generation and permutation of difference,” but, in contrast to structuralism, post-structuralism “acknowledges that meaning may be inherently unstable, that the process of signification is unlimited and that differences reproduce themselves indefinitely” (45).

- “… post-structural narratology puts the emphasis on the inherent incompleteness of narratives” (45).

- i.e., the structures are not just fixed and pre-given, but are continually being created and re-formed by our engagement with them.

- This is especially important to be aware of in our duty/attempt to identify and avoid falling prey to “grand narratives” (“totalizing or centralizing theories of meaning” (45)).

- Being aware of the pitfalls of grand narratives, thus, aware to their constant evolution by our engagement with them, means our emphasis on our “more active, intervenionist or inter-active role” in the creation and employment of meaning.

- Post-Structuralist proponents (named by the authors): Roland Barthes, Julia Kristeva, Jacques Derrida, and Michel Foucault (45).

Mikhail Bakhtin: “maintained that any utterance—be it of a purely linguistic nature or, like verbal or filmic narrative made up of different, interwoven symbolic orders—presupposes and refers to other utterances, i.e., it simultaneously represents an offer (inviting a response) and an answer (to an implied question)” (45-46).

- i.e.: utterances are always a call and response—they ask and tell.

- i.e., texts have complex semiotic structures …

- e.g., their meaning-structures operate on various levels of relations between their addressors, addressees, senses, and referents;

- … & are dialogical …

- e.g., creative of communicative bonds between the discussants that oblige them to collectively ask-and-tell in the co-creation and playing out of meaning.

Bakhtin’s “unfinalizability”: (the continually opening and building nature of texts that is always ongoing) also has a temporal dimension:

- Utterance X presupposes previous utterances and anticipates future utterances: (quoting Bakhtin) “every utterance is emitted in anticipation of the discourse of an interlocutor” (46).

- This means that every text is heteroglossia, is polyglottic: composed of many voices. One of these many voices of any text is yours … the reader/spectator becomes part of the “perception-reception-participation” of the work (46).

- e.g., recall Foucault’s analysis of Veláquez’s “Las Meninas”: the painted painter’s line of sight transgresses the frame of the actual painting to connect to us, “and links us to the representation of the picture” (A&S, 444).

- This means that every text is heteroglossia, is polyglottic: composed of many voices. One of these many voices of any text is yours … the reader/spectator becomes part of the “perception-reception-participation” of the work (46).

“The transitional or in-between spaces that earlier we described as ‘thresholds’ can in Bakhtin’s sense also be understood as moments of hesitation that invite new openings that need to be activated and performed by the spectators” (46).

Thus … “text, context and paratext function as so many passages or portals through which energies circulate that implicate the spectator and respond to his/her particular input” (46).

Thus … let us engage a Post-Structuralist narratological analysis of John Ford’s “The Searchers”:

Authors cite a branch of post-structuralist narratology: Garrett Stewart’s conversion of film narratology into “narratography” (47).

Thierry Kuntzel, likewise, emphasizes the post-structuralist lens on film openings—a “formal analysis of classical narratives as a dynamic process, which he labels ‘the work of film’” (47).

He is addressed here for his especial note of Doors:

Thus … let us engage a Post-Structuralist narratological analysis of John Ford’s “The Searchers”:

- The Opening: not so much a thrust in media res (in the middle, without preamble), but “a beginning of an encounter,” a “metatext disguising itself as an action in media res” (46):

- It introduces the fundamental binary: culture/nature, soldier/settler;

- It comments on the genre of The Western.

- Thereby … the opening draws our attention to the genre’s central myths.

- “As spectators, our view is initially framed by the darkness of the doorway (doubling the darkness of the auditorium), thus underlining the distance that separates us in both time and space from this West, a wholly mythologized past which now comes to us through such highly self-reflexive reconstructions as John Ford, his cinematographer and screenwriter give us” (46).

- The film is enacting its own deconstruction of the West; it is “post-classical” (46)—citing the mythology while telling its story. It draws us into its dialogue (47).

- “As spectators, our view is initially framed by the darkness of the doorway (doubling the darkness of the auditorium), thus underlining the distance that separates us in both time and space from this West, a wholly mythologized past which now comes to us through such highly self-reflexive reconstructions as John Ford, his cinematographer and screenwriter give us” (46).

Authors cite a branch of post-structuralist narratology: Garrett Stewart’s conversion of film narratology into “narratography” (47).

- i.e., essentially giving the ‘image’ even greater agency in meaning creation, as if the ‘image’ is like the cartographer who creates a map by walking grounds—these surfaces walked are as contributory to meaning as the plot’s characters, etc.

Thierry Kuntzel, likewise, emphasizes the post-structuralist lens on film openings—a “formal analysis of classical narratives as a dynamic process, which he labels ‘the work of film’” (47).

- A “multi-faceted and stereometric approach to narrative [that] gave the films he analyzed both ‘body’ and ‘volume’” (47).

He is addressed here for his especial note of Doors:

“… to open or close a door, to enter or cross a space, produces specific meaning, but also acts as a punctuation mark or a shift of register …” and forms the “first, linear level of the film”; the second dimension is how the door is a passage through the mystery and leads to the original void (48).

- i.e.: passage through passageways:

- level one: produces specific meaning & marks a shift of register;

- level two: & passes through mystery back to original void.

“Emptiness or absence … in keeping, perhaps, with the psychoanalytic belief that (primordial) lack always functions as catalyst and stimulus” (48).

- i.e., consider how desire is classically defined as a lack (you desire what you do not have); such a lack inspires and motivates you to seek or chase it.

|

“The paradoxical motif of absence as a perpetuum mobile [perpetual motion] explicitly harks back to Sigmund Freud and his idea of dream-work …” (48).

Kuntzel’s supposition was that “the entire film is folded or condensed into the opening scenes, at once prefiguring what follows in a kind of mini-narrative, and anticipating it in condensed and encrypted form, by exploiting to the maximum the ‘polysemic’, ambiguous nature of words, such as ‘game’, of gestures of welcome or entry, and even of acts and actions, such as rescue and shelter” (48).

For Neo-Formalists: “mental and emotional engagements are a matter of carefully feeding information to the spectator or withholding it at certain points, to create suspense, fright or mystery” (49).

For Post-Structuralists: “‘film-work’ … also requires the spectator to be fully engaged, but the information s/he receives is present in often coded form that requires special interpretative keys …” (49).

A critique of Post-Structuralism often thus comes in the form of an accusation of its being outside of and superior to the work under analysis. That it is distanced from art. That it ‘tells’ art what it means, presuming art itself is ignorant.

More importantly is the awareness of the varying recognition of the gaps of overt and covert and unconscious meaning, and its being generative of what Paul Ricoeur called the “hermeneutics of suspicion” (49). Narratives, e.g. films, can seem innocuous, but covertly enforce normative dictates.

- i.e., this is an example of the one and identical issue postmodernism has against ‘grand narratives’: they perpetuate and enforce certain dictates; even as we can identify them as biases or clichés, think them innocuous, think ourselves knowingly skeptical, we are still always and constantly falling prey to them …

- e.g., we are ‘hard-wired’ and trained to think in hierarchical ways (finding roots, trancing out branches, delineating lines of causality, ranking things in lists, ordering things in groups, etc.), so think of how we have many specific societal groups divided into more specific groups, be it basketball and women’s basketball, poets and poets of color, writers and southern writers … while these divisions hone our knowledge generally by addressing attributes by which to clump or divide things, and there is nothing inherently problematic about divisions, the criteria by which we divide says something about our base mindsets, about our fundamental conditioning of what is ‘normal’ (we frequently divide by gender, color, age, nationality, etc., not alphabetically or by favorite color, etc.), and can therefore blur the seemingly empirical divisions into judgments of value (be it traditional versus new, better to worse, mainstream to fringe, etc.), and the more we use these divisions, the more we continually train ourselves to adhere to their demarcations.

The years of post-structuralist critics, and how mainstream their method and many of their ideas have become, has generally birthed a tendency we see today in critical analysis trying to “let films speak for themselves” (49)—a soundbite that is to be carefully understood as a listening that is keenly aware to the influence at once of the listener on the listening.

- Authors cite Gilles Deleuze on this point, an opening up of the multi-sensory giving and receiving of meaning wherein the critic should not discourse about but discourse with and through film (49).

So … Back to DOORS with these insights in mind:

- “In this sense, the door as the central motif of cinema is useful in that it evokes a number of visual and conceptual terms that bring to the fore a film’s spatial and narrative logics. Yet it also adds a rich field of metaphoric associations: a door can hide and conceal but it can also reveal and open, or do both at the same time, echoing features of the screen that we discussed in our etymological sketch above” (49).

- The DOOR can be like a character in film:

- e.g.: ‘keyhole films’; hiding behind ‘secret doors’; foreground acoustic versus visual perception; block access or provide impetus through transgression of blocked access … (50)

- Doors … can signal crossing from here to there physically or through time or ontologically (changing from being this being to being that being) or cosmologically (from this universe to that universe) … (50-51)

- Doors … can signal metaphors … opening to bright futures, getting a foot in the door, having doors clammed in your face, bolting doors after your horses have already fled, gates of heaven, etc. … (51)

- Doors … especially signal liminal zones in the internet age and, earlier but also still, in mental or internal worlds (e.g., ‘doors of perception’ from William Blake to Aldous Huxley to Jim Morrison) … hence, too, cinema as a “trip” … (51)

- Doors … also especially speak to women’s role in the domestic sphere … be it in Gothic romance, horror-thrillers, or family melodramas … (e.g. Matthias Müller’s “Home Stories” (1990)—compiling clips from 40’s-50’s, telling of “restless sleep, awakening, eavesdropping at the door, switching on the lights, surprise, anxiety, [all] mostly conveyed through opening and closing doors” (52) … such doors allowing focus on women, and showing their captivity (53)

So … all the films mentioned in this reading reveal shared and overlapping components of plural-meanings opened up by the many facets of doors (doors, thresholds, passages, screens) discussed herein.

- This moreover reveals that cinema “as apparatus and dispositif is made up of discrete parts that are in tension to each other even as they work together, and which—at a conceptual level—may well stand in opposition to each other” (53).

- “dispositif”: literally the French word for ‘device’ or ‘plan’, dispositif is a term popularized by Foucault that means the mechanisms and power structures that enhance and maintain power within a social body.

- E.g.:

- The Projector & The Screen:

- –Work together, but also in conflicting ways: the project lights up thus disperses, scatters, light on the screen, while the screen masks, gathers, the light together by bounding it by the dark frame or curtains to focus it and reveal the picture …

- Screen as Window & Filter:

- –The transparency of the window and opacity of the filter work together and counter one another in terms of unmediated and mediated access, by direct access or constructed representation …

- Screen as Semi-Permeable Membrane:

- –The film gives the spectator entry into it, but also occludes and dictates our entry by editing; editing ‘weaves’ us into its narration, into what is screened, like a suture …

- e.g.: Woody Allen’s “The Purple Rose of Cairo” (1985) most explicitly revolves around the Screen as Semi-Permeable Membrane because its storyline is of a film’s actor who leaps from the silver screen to be with a young woman who has repeated visited its screenings … the story involves the changes in ‘reality’ the filmed-actor-cum-film’s-real-character encounters as much as the changes in the ‘film’-world-within-the-film’s-world.

- –The film gives the spectator entry into it, but also occludes and dictates our entry by editing; editing ‘weaves’ us into its narration, into what is screened, like a suture …

- The Projector & The Screen:

“Summing up the idea of cinema as door and screen, we can say that it is a bodily concept indicating crossing or transgression: the spectator enters metaphorically ‘another world’ or experiences his/her own world as foreign and strange, while retaining an awareness of entry and transition, rather than remaining in the state of witnessing a display an exhibition and an unveiling” (54).

“This movement passage, transport and transposition, though, is relativized by the (literal as well as etymological and metaphorical) fixity and immobility of the components of the cinema” (54).

“… the door and the screen, acting as sieve and filter, draw our attention to the partial permeability of the image” (54)—awakening ideas of exchange, dialogue … film induces physical presence and spatiality while paradoxically remaining abstract, artificial, and self-enclosed.

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by MacHighway