B O O K & F I L M L I S T S :

recommendations as to what to read & see

CONTENTS:

- 0) Preface: On Books

- I) In General (historical & topical)

- II) Existentialism

- III) Existential Films

- IV) Aesthetics (philosophy of film; ...)

- V) Philosophy of Science (antiquity to Newton)

- VI) Environmental & Philosophy of Nature

- VII) Gender Studies

- VIII) Gender Studies Films

- IX) Philosophical Films

0) Preface (On Books):

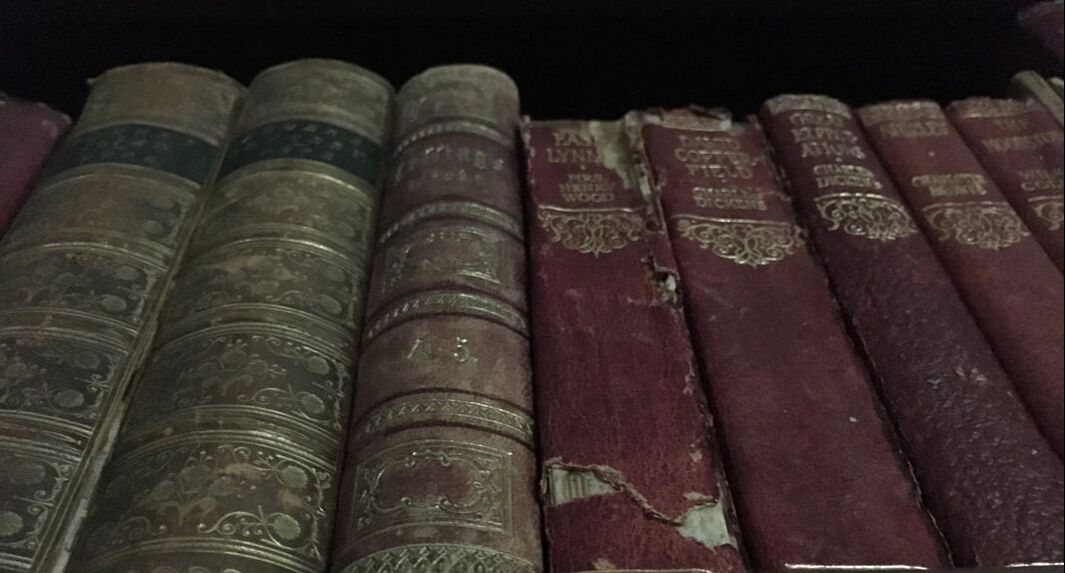

Around the first century of the common era we moved from ancient clay tablets and papyri, cloth, and parchment scrolls (which suffered more weather and survive today in far worse repair) to manuscripts, works printed in pages (often on vellum, thin milky-colored sheepskin, typically bundled into 'signatures'), and when contained between two covers (typically made of wood), that is, to what we call 'codices,' but recognize simply as 'books.'

Around the first century of the common era we moved from ancient clay tablets and papyri, cloth, and parchment scrolls (which suffered more weather and survive today in far worse repair) to manuscripts, works printed in pages (often on vellum, thin milky-colored sheepskin, typically bundled into 'signatures'), and when contained between two covers (typically made of wood), that is, to what we call 'codices,' but recognize simply as 'books.'

On Form (the parts within books): |

When these manuscripts are richly decorated—as most of them were—we call them illuminated manuscripts. The medieval period may be understood as intimated connected to bookmaking; its legacy is inseparable from the laborious copying of ancient writings and dissemination of texts. Such required innovation in language, translation, construction of books, etc. Under Charlemagne, himself illiterate, the Western world saw the greatest intellectual advance (return to its past glory?) of the middle ages (perhaps second only to the 15th c. invention of the Gutenberg Press in terms of import) with the introduction of the Carolingian Minuscule, a script, called a “book-hand,” that introduced clear uppercase letters, first contained the newly invented lower case letters, added spaces between words, and standardized overall the Roman alphabet. With this script, books could be reproduced with greater speed and more universally understood. The technical aspects of books should not be ignored—these elements can actually shed great light on the very content of the works.

|

|

Beyond the covers and titles, the first little element to hit one is often the EPIGRAPH. This is a short quote or quip, sometimes by the author, but much more commonly a quote of someone else. Their choice by authors is exceedingly intentional; much should be read into the work from what and how the epigraph reads. Cf., Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, where Johannes de silentio begins with a quote from Hamann about Tarquinius Superbus, an early King of Rome, (“What Tarquin the Proud said in his garden with the poppy blooms was understood by the son but not by the messenger,” p.39 in Hannay trans.) which exemplifies indirect communication and features a father and son.

A PREFACE (Latin, prae-, before, -factum/-fari, spoken or made, borrowed into English through the Old French in the 14th c. where it mean “that opening part of sung devotions”) is written by the book’s author and typically addresses the ‘meta’ dimension of the book: how did it come to be or what gave him or her reason to write it; methods, pedagogy, or aims of the writing. (One can see these used very frequently in early Greek medical and scientific texts where they state method, but also in philosophical and literary works.) It may well end with acknowledgements of others who contributed in some way to the book, its coming to be, or to the author and thereby to the book. They are occasionally signed and dated by the author. William Smellie begins the preface to his 18th c. work of natural history with what has become a well-cited remark on the nature and import of prefaces (read “f” as “s”): “Every Preface, befide occafional or explanatory remarks, fhould contain not only the general defign of the work, but the motives and circumftances which induced the author to write upon that particular fubject. If this plan had been univerfally obferved, prefaces woulf have exhibited a fhort, but a curious and usfeful, hiftory both of literature and of authors” Within Christianity, “preface” also specifically names the introduction to the central part of the Eucharist (the opening “thanksgiving” in which the priest glorifies and thanks God), hence forming the first part of the canon or prayer of consecration. However, one of the richest prefaces we will read is Descartes’ ‘preface to the reader’ in his Meditations, wherein close scrutiny of the tone tells us more about his work’s content than his introduction. Such tonal revelations should also be noted in Kierkegaard’s pseudonymous works.

(The preface’s opposite is the POSTFACE, which is a piece, typically written by the author, that follows the text; it can be like a conclusion, but typically one that stands at a distance, more a final reflection on the text, or like an appendix, concluding with information or ideas that are supplemental to the work.) A FOREWARD is also a reflection upon the book in full (more so than just its content), but is typically written by another person besides the book’s author. They are almost always signed and dated by the forward-writer. The term in this meaning only really dates from 1842, perhaps borrowed from the German Vorwort, “preface,” yet meant to designate a difference from preface per se. An INTRODUCTION is written by the book’s author, but addresses more closely the actual content within the book (versus reflections upon the nature or genesis or goals of the book). Such is deemed part of the book, as opposed to a part of the ‘frontmatter.’ In the tradition, a preface comes first (and, if there are multiple prefaces, the newest come first), then a foreword, then the introduction. Occasionally newer forewords will replace older forewords, but different prefaces will be kept. Where things become more confusing is in the consideration of prologues, proems/exordiums, etc.: A PROLOGUE also is a “before” “word,” (in English, it originates in the early 12th c. from the Latin and Greek prologus) but is in between an authorial or non-authorial reflection upon the text (they may be written by the author, or added later by other writers or editors) and an introduction to the text’s content: it, more so, establishes the setting in full or theme or tone that is before what will be told in the content (sometimes a back story to characters or ideas, sometimes a prehistory, etc., sometimes epigraph-like, sometimes like a soliloquy, medievals enjoyed homilies serving as prologues). Prologues are perhaps most common in early Greek drama (esp. Euripides but can be traced back to manuscripts from the 5th c. BCE and also in Persian), although early Latin literature generally made them longer and more elaborate, esp. Chaucer’s excessive prologues, instead of one in the beginning, having many before all his stories in Canterbury Tales; Renaissance dramatic works saw fewer prologues and transformed them more to theatrical direct addresses from a character, or actor denuded of character traits, to the audience or reader (at which point they came to serve more like a text’s preface, adding a meta-reflection upon the work itself as a work). PROEMS (Greek, pro-, before, -oimos, way or song, often prelude; in English, it roughly originates in the 14th c.) and EXORDIUMS (Latin, “beginning” or “to urge forward,” roughly originates in 16th c.) are the most confused. Often, a proem is meant synonymous with preface, although just as often serves more like an introduction, even as they are often deemed synonymous to exordiums, which equally blend aspects of the preface and introduction. Plato’s Phaedrus and Aristotle’s Rhetoric address proems as the prologue-like part of an ideal rhetorical address. Exordium are more often linked with late antique/medieval dispositios, serving as their first part and blending operations of prefaces and introductions: they come before arguments (the) and often delineate the flow of the argument, although also both reflect upon the purpose of the argument, its style and requirements, and the qualifications of the arguer (like prefaces) and the content itself (like introductions). |

|

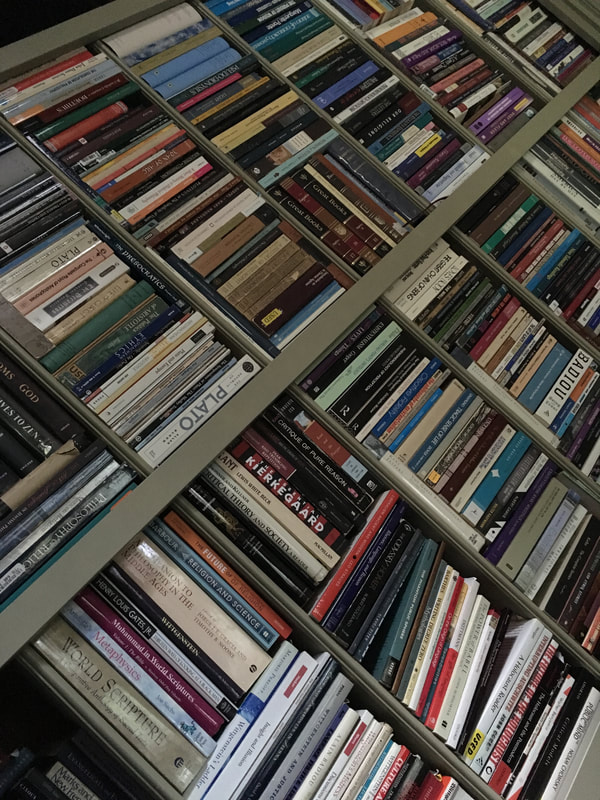

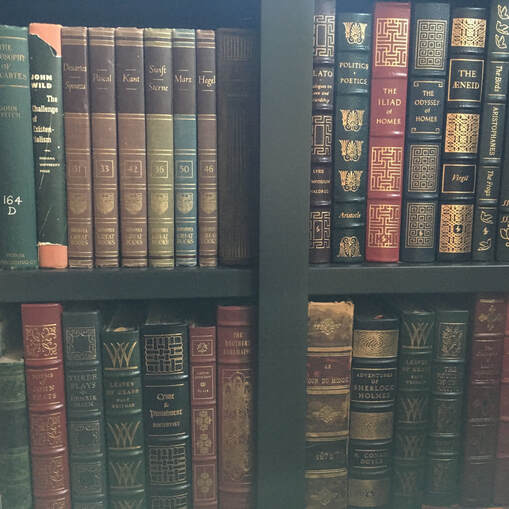

I) In General

(divided historically & topically, ideal for those newer to philosophy &

those filling in gaps in one's studies):

- Great Ancient Texts:

- Plato, The Trial & Death of Socrates, trans. John Cooper & G.M.A. Grube (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2001).

- Plato, Five Dialogues: Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Meno, Phaedo, trans. G.M.A Grube (Hackett, 2002) ISBN-13: 978-0872206335.

- Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, trans. Terence Irwin (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 2000), isbn: 0-87220-464-2.

- Chuang Tzu, Chuang Tzu: Basic Writings, trans. Burton Watson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), isbn: 0231105959.

- Great Medieval Texts:

- Augustine, The Confessions of Augustine, trans. Rex Warner (New York: Penguin Putnam, Inc., 2001).

- Augustine, On the Free Choice of the Will, trans. Thomas Williams (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 1993).

- Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy, trans. Richard H. Green (Mineola, NY: Dover Pub., Inc., 2002).

- Pseudo-Dionysius, Complete Works of Pseudo-Dionysius, tran. Colm Luibheid (Mahwah: Paulist Pr., 1987).

- Al-Ghazzali, On Knowing Yourself and God, tr. Muhammad Nur Abdus Salam (Chicago: KAZI pub., 2002).

- Anselm, Proslogion, with the Replies of Gaunilo & Anselm, tr. Thomas Williams (Indianapolis: Hackett P., 2001)

- Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I, The Treatise on the Divine Nature, trans. Brian J. Shanley (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 2006).

- Farid Ud-Din Attar, The Conference of the Birds, trans. Afkham Darbandi and Dick Davis (New York: Penguin Books, 1984). Isbn: 978-0-14-044434-6.

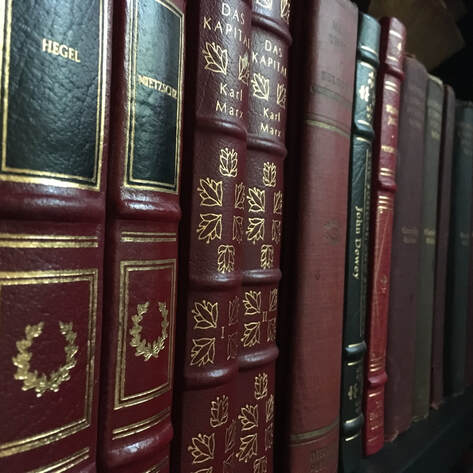

- Great Modern Texts:

- René Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy, trans. Donald Cress (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 1993), isbn: 0872201929.

- Immanuel Kant, Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals, trans. James W. Ellington (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 1993), isbn: 087220166X.

- John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism, ed. George Sher (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2002), isbn: 087220605X.

- Søren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling, trans. Alastair Hannay (New York: Penguin Books, 1985).

- Søren Kierkegaard, Concept of Anxiety, trans. Reidar Thomte (Princeton: Princeton U.P., 1981), isbn: 978-0691020112.

- Søren Kierkegaard, The Sickness Unto Death, trs. Howard & Edna Hong (Princeton: Princeton U.P., 1980), isbn: 978-0691020280.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy and the Genealogy of Morals, trans. Francis Golfing (New York: Anchor Books, 1956), isbn: 0385092105.

- Kafka’s Metamorphosis and Other Stories, trans. Donna Freed (Barnes & Noble Classics Series, 2003), ISBN: 1593080298.

- Great Contemporary Texts:

- Martin Buber, I and Thou, trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Touchstone, 1971), isbn: 9780683717258.

- Jean-Paul Sartre, Nausea, trans. Lloyd Alexander (NY: New Directions Pub., 1969), isbn: 9780811217002.

- Jean-Paul Sartre, Existentialism is a Humanism, trans. Carol Macomber (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), ISBN: 0300115466.

- Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, trans. Joan Stambaugh (NY: State University of New York Press, 2010), isbn: 1438432763.

- Martin Heidegger, Basic Writings: Ten Key Essays, plus the Introduction to Being and Time, ed. David Farrell Krell (NY: Harper Perennial Modern Collins, 2008), isbn: 0061627011.

Levinas, Existence and Existents, trans. Robert Bernasconi, isbn: 978-0820703190. - Jean-François Lyotard, The Differend: Phrases in Dispute, trans. Georges Van Den Abbeele (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988), isbn: 0816616116.

- A very challenging read, though! Lyotard himself reports: “Despite every effort to make his thought communicable, the A. [author] knows that he has failed, that this [book] is too voluminous, too long, and too difficult” (xv), and: “In writing this book, the A. had the feeling that his sole addressee with the Is it happening? … And, of course, he will never know whether or not the phrases happen to arrive at their destination, and by hypothesis, he must not know it” (xvi).

- Jean-Luc Nancy, Noli me Tangere: On the Raising of the Body, trans. Sarah Clift, Pascale-Anne Brault, Michael Naas (NY: Fordham University Press, 2008).

- Jean-Luc Nancy, Listening, trans. Charlotte Mandell (NY: Fordham UP, 2007), isbn: 9780823227730, $25.

- Jean-Luc Nancy, Dis-Enclosure: The Deconstruction of Christianity, trans. Bettina Bergo, Gabriel Malenfant, Michael B. Smith (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), isbn: 9780823228362

- Another very challenging read! Nancy himself wrote: “A simple warning for those who will not already have thrust aside this book in fury, pity, or discouragement. What follows here does not constitute the sustained and organized development one might expect. It is only an assembly, wholly provisional, of diverse texts that turn around the same object without approaching it frontally. It has not yet seemed to me possible to undertake the more systematic treatment of this object, but I thought it desirable to put to the test [these] texts … I do not feel particularly secure in this undertaking: everywhere lurk traps” (12).

- Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (New York: Grove Press, 2011), ISBN: 080214442X.

- Jacques Derrida, On the Name, trans. David Wood, John P. Leavey, jr., Ian McLeod (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995), isbn:9780804725552

- Jacques Derrida, On the Name, trans. David Wood, John P. Leavey, jr., Ian McLeod (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995), isbn: 9780804725552.

- Another challenging read! Derrida wrote: “In reading it, [this book,] … a difficulty suddenly arises, a sort of dysfunctioning, what could be called a crisis. … At a certain place in the system, one of the elements of the system … no longer knows what it should do. More precisely it knows that it must do contradictory and incompatible things. Contradicting or running counter to itself, this double obligation thus risks paralyzing, diverting, or jeopardizing the successful conclusion … one or more than one participant, indeed the master of ceremonies himself, may somehow desire the failure …” (4-7).

- Jacques Derrida, Monolingualism of the Other or The Prothesis of Origin, trans. Patrick Mensha (Stanford: Stanford U.P., 1998), isbn: 0804732982.

- Another challenging read!, Derrida writes: “In a sense, nothing is untranslatable; but in another sense, everything is untranslatable; translation is another name for the impossible” (56-7).

- Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), isbn: 978-0816614028.

- Giorgio Agamben, Idea of Prose, trans. Michael Sullivan and Sam Whitsitt (New York: SUNY University Press, 1995).

- Giorgio Agamben, The End of the Poem: Studies in Poetics, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999).

- Great for Aesthetics / Philosophy of Art:

- Art and its Significance: An Anthology of Aesthetic Theory, third edition, ed. Stephen David Ross (New York: State University of New York Press, 1994). ISBN: 978-0791418529. List Price: $31.95. A wonderful, large collection of diverse writings by philosophers, scholars, and artists.

- Great for Philosophy of Religion:

- Walter Kaufmann, Critique of Religion and Philosophy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990). Isbn: 0-691-02001-9, $14.95.

- Augustine, The Confessions of Augustine, trans. Rex Warner (New York: Signet Classic, Penguin Putnam, Inc., 2009). Isbn: 0-451-53121-3, $6.95.

- Hermann Hesse, Siddhartha, trans. Hilda Rosner (New York: Bantam Classics, 1981). Isbn: 978-0553208849, $5.99.

- Søren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling, trans. Alastair Hannay (New York: Penguin Books, 1985). Isbn: 978-0-14-044449-0, $14.00.

- Farid Ud-Din Attar, The Conference of the Birds, trans. Afkham Darbandi and Dick Davis (New York: Penguin Books, 1984). Isbn: 978-0-14-044434-6, $15.00.

- Rudolf Otto, The Idea of the Holy, trans. John W. Harvey (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1958). Isbn: 978-0195002102, $16.95.

- William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience, trans. Jaroslav Pelikan (New York: Library of America, 2009). Isbn: 978-1598530629, $13.95.

- William James, The Will to Believe (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2012). Isbn: 978-1470179618.

- Sigmund Freud, The Future of an Illusion, trans. James Strachey (W. W. Norton & Company, 1989). Isbn: 978-0393008319.

- Great Ethics Texts:

- Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, trans. Terence Irwin (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 2000), isbn: 0-87220-464-2, $14.95.

- Augustine, On the Free Choice of the Will, trans. Thomas Williams (Indianapolis: Hackett Pubs., 1993), isbn: 0872201880, $9.95.

- Immanuel Kant, Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals, trans. James W. Ellington (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 1993), isbn: 087220166X, $8.95.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy and the Genealogy of Morals, trans. Francis Golfing (New York: Anchor Books, 1956), isbn: 0385092105, $11.00.

- Colin McGinn, Moral Literacy or How to Do the Right Thing (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1993), isbn: 9780872201965, $14.

- John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism, ed. George Sher (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2002), isbn: 087220605X, $4.95.

- Plato, The Trial and Death of Socrates, trans. John Cooper & G.M.A. Grube (Indianapolis: Hackett Pub., 2001), isbn: 0872205541, $4.95.

- Simon Wiesenthal, The Sunflower: On the Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness (New York: Schocken Books), 1998, ISBN: 978-0-8052-1060-6, $15.95.

- Etienne Gilson, Three Quests in Philosophy (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies (PIMS), 2008, isbn: 978-0-88844-731-9, price: $25.95.

- Placing Nature on the Borders of Religion, Philosophy and Ethics, eds. Forrest Clingerman and Mark H. Dixon (Surrey, United Kingdom: Ashgate Publishers, August 2011). ISBN: 978-1-4094-2044-6.

- Thinking about Love: Essays in Contemporary Continental Philosophy, eds. Diane Enns and Antonio Calcagno (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2015). ISBN: 978-0271070964.

|

“Do we in our time have an answer to the question of what we really mean

by the word ‘being’? Not at all. So it is fitting that we should raise anew the question of the meaning of being. But are we nowadays even perplexed at our inability to understand the expression ‘being’? Not at all. So first of all we must reawaken an understanding for the meaning of this question” —Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, xix. |

“You are in part what we make you up to be, and we are in part what you make us up to be.”

--María Lugones, Pilgrimages/Peregrinajes: Theorizing Coalition against Multiple Oppressions (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2003), 74.

--María Lugones, Pilgrimages/Peregrinajes: Theorizing Coalition against Multiple Oppressions (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2003), 74.

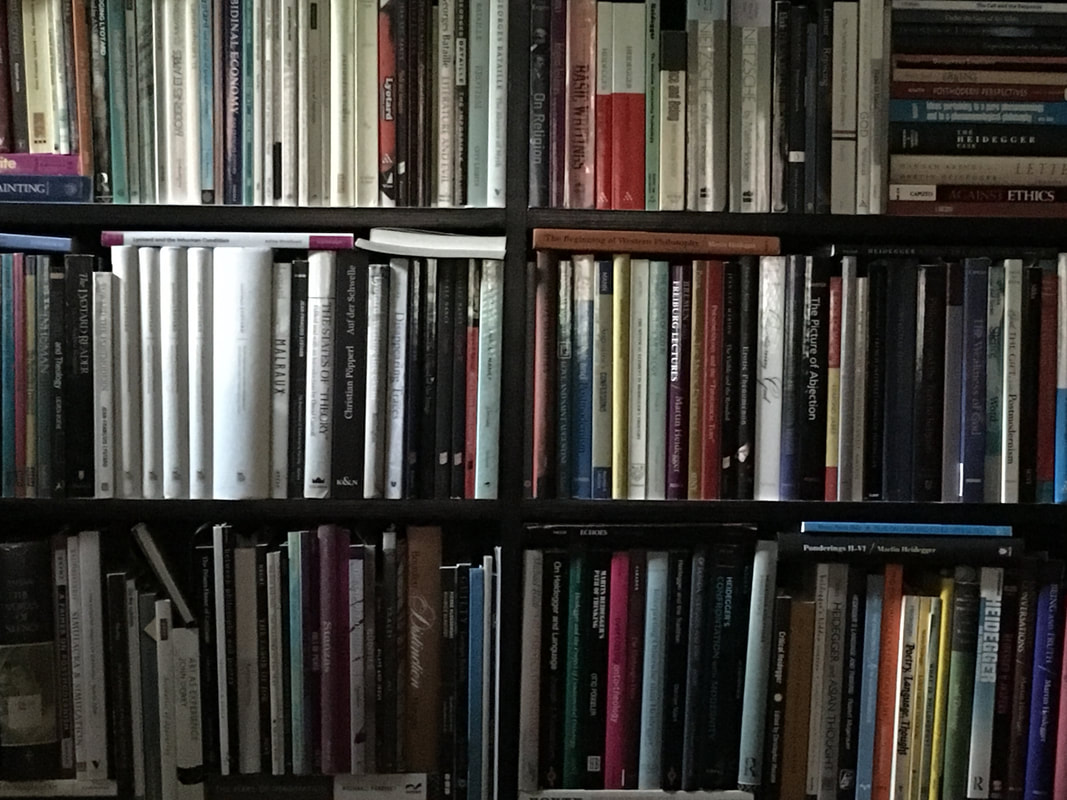

II) Existentialism:

- Theodor Adorno & Max Horkheimer, Ch. 1, The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception (www.marxists.org/reference/archive/adorno/1944/culture-industry.htm).

- Simone de Beauvoir, The Ethics of Ambiguity (www.marxists.org/reference/subject/ethics/de-beauvoir/ambiguity/index.htm).

- Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot (NY: Grove Press, 2011), 978-0802144423.

- ----. End Game.

- Albert Camus, The Stranger

- ----. The Myth of Sisyphus

- Charles Darwin, Ch. III: “Struggle for Existence,” Origin of Species (www.marxists.org/reference/archive/darwin/works/origins/ch03.htm).

- Franz Fanon, “Reciprocal Bases of National Culture and the Fight for Freedom,” Wretched of the Earth(www.marxists.org/subject/africa/fanon/national-culture.htm).

- José Ortega y Gasset, “Man has no Nature”

- G.W.F. Hegel, “Lordship & Bondage,” Phenomenology of Spirit (www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/index.htm).

- Martin Heidegger, Basic Writings, ed. David Farrell Krell (NY: Harper Perennial, 2008), 978-0061627019.

- Martin Heidegger, “The Question Concerning Technology,” “The Letter on Humanism,” in Basic Writings.

- Franz Kafka, The Trial

- Søren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling, tr. Alastair Hannay (NY: Penguin, 1986), 978-0140444490.

- ----. The Sickness Unto Death, trs. Howard & Edna Hong (Princeton UP, 1980), 978-0691020280.

- ----. The Present Age [The Present Moment]

- Emmanuel Levinas, Existence and Existents, tr. Robert Bernasconi (Pgh: Duquesne UP, 2001), 978-0820703190.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Ch. II “The Free Spirit,” Beyond Good and Evil (www.marxists.org/reference/archive/nietzsche/1886/beyond-good-evil/ch02.htm).

- Willis Regier, “Cioran’s Insomnia,” MLN 119, 5 (2004): 994-1012 (on Blackboard).

- Jean Paul Sartre, Nausea, tr. Lloyd Alexander (NY: New Directions, 1969), 978-0811217002.

- Jean-Paul Sartre, “The Wall,” (http://chabrieres.pagesperso-orange.fr/texts/sartre_thewall.html).

- Miguel de Unamuno, “The Practical Problem,” Tragic Sense of Life, 260-296.

“More than any other time in history, mankind faces a crossroads.

One path leads to despair & utter hopelessness. The other, to total extinction.

Let us pray we have the wisdom to choose correctly.”

–Woody Allen, Side Effects, 81.

One path leads to despair & utter hopelessness. The other, to total extinction.

Let us pray we have the wisdom to choose correctly.”

–Woody Allen, Side Effects, 81.

III) Existential Films:

- Igmar Bergman’s “Through a Glass Darkly” (Swedish, 1961), “Winter Light” (1963), “The Silence” (1963), “The Seventh Seal” (1957), “Wild Strawberries” (1957), or “Persona” (1966).

- Krzysztof Kieslowski’s “The Decalogue,” any in series of 10 (Polish, 1988), “The Double Life of Veronique” (1991).

- David Lynch’s “Lost Highway” (American, 1997), “Mulholland Dr.” (2001), “Inland Empire” (2006).

- Akira Kurosawa’s “Ikiru” (Japanese, 1952), “Rashomon” (1950).

- Robert Bresson’s “Diary of a Country Priest” (French, 1951).

- Hiroshi Teshigahara’s “Face of Another” (Japanese, 1966).

- Andrei Tarkovsky’s “Stalker” (Russian, 1979), “Ivan’s Childhood” (1962).

- Gabriel Axel’s “Babette’s Feast” (Danish, 1987).

- Wim Wender’s “Wings of Desire” (German, 1987), “Paris, Texas” (1984).

- Marco Bellocchio’s “My Mother’s Smile” (Italian, 2002).

- Michael Haneke’s “Time of the Wolf” (German director, film subtitled from French, 2003).

- Coen Brothers, “No Country for Old Men” (American, 2007).

- David Cronenberg’s “Spider” (Canadian, 2002) or “A History of Violence” (2005).

- Olivier Assayas, “Cold Water” (French, 1994).

- Khyentse Norbu’s “Travellers and Magicians” (Bhutanese, 2003).

- Bruno Dumont’s “Hadewijch” (French, 2009), “Jeannette: The Childhood of Joan of Arc” (2018).

- Alain Resnais’ “Last Year at Marienbad” (French, 1962).

- Werner Herzog, “The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser” (German, 1974).

- Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s “Mother Küsters goes to Heaven” (German, 1985).

- Chris Marker’s “La Jetée” (French, 1962).

- François Truffaut’s “Jules et Jim” (French, 1962).

- Robert Altman’s “3 Women” (French, but film in English, 2010).

- Harmony Korine’s “Mister Lonely” (American, 2007).

- Jim Jarmusch’s “Broken Flowers” (American, 2005).

- Woody Allen’s “Crimes and Misdemeanors” (American, 1989), “Sleeper” (1973), “Interiors” (1978), “Zelig” (1983), “Alice” (1990), “Melinda and Melinda” (2004), “Midnight in Paris” (2011), “Blue Jasmine” (2013).

- Roberto Rossellini’s “The Flowers of St. Francis” (Italian, 1950).

- Alejandro Jodorowsky’s “The Holy Mountain” (Mexican, 1973).

- Álex de la Iglesia’s “Oxford Murders” (Spanish director, film in English, 2008).

- Claire Denis, “Let the Sun Shine In” (French, 2017).

- Hitchcock’s “Rope” (American, 1948), “Rear Window” (1954), “Vertigo” (1958).

- Spike Jonze’s “Being John Malkovich” (American, 1999).

- Peter Howitt’s “Sliding Doors” (British, ‘98).

- Marc Erlbaum’s “Café” (American, 2010).

“Unless a man aspires to the impossible, the possible that he achieves

will be scarcely worth the trouble of achieving”

—Miguel de Unamuno, Tragic Sense of Life.

will be scarcely worth the trouble of achieving”

—Miguel de Unamuno, Tragic Sense of Life.

IV) Aesthetics: Philosophy ofFilm

Edited Collections:

Single Author:

- America on Film: Representing Race, Class, Gender, and Sexuality at the Movies. Second Edition. Edited by Harry M. Benshoff and Sean Griffin. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

- Faith, Film and Philosophy: Big Ideas on the Big Screen. Edited by R. Douglas Geivett and James S. Spiegel. Intervarsity Press, 2007.

- Film as Philosophy: Essays on Cinema after Wittgenstein and Cavell. Edited by Rupert Read and Jerry Goodenough. NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

- Film Theory and Philosophy. Edited by Richard Allen and Murray Smith. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Introducing Philosophy Through Films: Key Texts, Discussion, and Film Selections. Edited by Richard Fumerton and Diane Jeske. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

- Movies and the Meaning of Life: Philosophers Take on Hollywood. Edited by Kimberly A. Blessing and Paul J. Tudico. Chicago: Open Court Press, 2005.

- Philosophy and Film: A Collection of Readings. Edited by Mike Awalt. Acton, MA: Copley Custom Publishing Group, 2001.

- Philosophy and Film. Edited by Cynthia A. Freeland and Thomas E. Wartenberg. NY: Routledge, 1995.

- The Philosophy of Film: Introductory Text and Readings. Edited by Thomas E. Wartenberg and Angela Curran. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2005.

- Purity and Provocation: Dogma 95. Edited by Mette Hjort and Scott MacKenzie. London: BFI Publishing, 2003.

- Race, Philosophy, and Film, eds. Mary K. Bloodsworth-Lugo and Dan Flory (New York: Routledge Studies in Contemporary Philosophy, 2013). ISBN: 978-0415624459.

- The Routledge Companion to Philosophy and Film. Edited by Paisley Livingston and Carl Plantinga. NY: Routledge, 2008.

- Screening the Sacred: Religion, Myth, and Ideology in Popular American Film. Edited by Joel Martin and Conrad E. Ostwalt, Jr. Westview Press, 1995.

- Wittgenstein at the Movies: Cinematic Investigations. Edited by Béla Szabados and Christina Stojanova. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2011.

Single Author:

- Cocteau, Jean. The Art of Cinema. Translated by Robin Buss. London: Marion Boyars, 1994.

- Corrigan, Timothy. New German Film: The Displaced Image. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1983.

- Crisp, C. G.. Eric Rohmer: Realist and Moralist. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988.

- ----. Genre, Myth, and Convention in the French Cinema, 1929-39. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002.

- Harrington, John. The Rhetoric of Film. NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc., 1973.

- Litch, Mary M. Philosophy Through Film. NY: Routledge, 2010.

- McGinn, Colin. The Power of Movies: How Screen and Mind Interact. NY: Vintage Books, 2005.

- Simons, Jan. Playing the Waves: Lars Von Trier’s Game Cinema. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2003.

- Singer, Irving. Cinematic Mythmaking: Philosophy in Film. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008.

- Sinnerbrink, Robert. New Philosophies of Film: Thinking Images. Bloomsbury Academic, 2011.

- Smith, William G. Plato and Popcorn: A Philosopher’s Guide to 75 Thought-Provoking Movies. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2004.

Additional Works in Aesthetics, beyond film:

- Jean-François Lyotard, “Preliminary Notes on the Pragmatic of Works: Daniel Buren,” October 10 (1979): 59-67.

- Babette Babich, “The Aesthetics of the Between: On Space and Beauty,” in Jeff Koons: The Sculptor, eds. Brinkmann, Ulrich, and Pissarro, 58-69.

- C.G. Kodat, “Conversing with Ourselves: Canon, Freedom, Jazz,” American Quarterly 55:1 (2003): pp.1-28.

- K. Cartwright, “Voodoo Hermeneutics/The Crossroads Sublime: Soul Musics, Mindful Body, and Creole Consciousness,” The Mississippi Quarterly 51:1 (2003-04): pp. 157-70.

- Michel Henry, “Monumental Art” and “Music and Painting” in Seeing the Invisible: On Kandinsky, pp.102-118.

“What secret is at stake when one truly listens, that is when one tries to capture or surprise the sonority rather than the message?” Because “to listen is to be straining toward a possible meaning, and consequently one that is not immediately accessible”

—Jean-Luc Nancy, Listening.

—Jean-Luc Nancy, Listening.

V) Philosophy of Science: Antiquity to Newton:

Thales (ca. 624-546 b.c.e.)

General & Misc. Secondary Texts, Histories, Anthologies, etc.:

- W.S. Anglin and J. Lambeck, The Heritage of Thales (Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics) (Springer, 1995)

- Partricia F. O’Grady, Thales of Miletus: The Beginnings of Western Science and Philosophy (Western Philosophy Series) (Routledge, 2002)

- Charles H. Kahn, Anaximander and the Origins of Greek Cosmology (Hackett, 1994)

- Radim Kocandrle and Dirk L. Couprie, Apeiron: Anaximander on Generation and Destruction (Springer, 2017)

- Martin Heidegger, The Beginning of Western Philosophy: Interpretation of Anaximander and Parmenides (Indiana UP, 2015)

- Early Greek Philosophy, trans./ed. Jonathan Barnes (New York: Penguin, 2002)

- The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library: An Anthology of Ancient Writings Which Relate to Pythagoras and Pythagorean Philosophy, trans. Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie (Phanes Press, 1987)

- Heraclitus: The Cosmic Fragments, trans. G. S. Kirk (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1954)

- Heraclitus: Greek Text with a Short Commentary, trans. M. Marcovich (Merida, Venezuela: Los Andes University Press, 1967)

- A. H. Coxon, The Fragments of Parmenides: A Critical Text with Introduction and Translation, the Ancient Testimonia, and a Commentary, edited and with new translations by Richard McKirahan (Las Vegas: Parmenides Publishing, 2009)

- The Texts of Early Greek Philosophy: The Complete Fragments and Selected Testimonies of the Major Presocratics, two volumes, ed. D. W. Graham, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010)

- B. Inwood, The Poem of Empedocles: A Text and Translation with an Introduction (Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Second ed., 2001)

- C.C.W. Taylor, The Atomists: Leucippus and Democritus: Fragments (Phoenix Presocractic Series) (University of Toronto Press, 2010)

- C.C.W. Taylor, The Atomists: Leucippus and Democritus: Fragments (Phoenix Presocractic Series) (University of Toronto Press, 2010)

- Timaeus and Critias, trans. Desmond Lee (New York: Penguin)--Timaeus being the relevant text, cosmological issues. OR Timaeus, trans. Peter Kalkavage (Hackett)

- The Complete Works of Aristotle, Vol. 1, ed. Jonathan Barnes (Princeton UP, 1984), including:

- Physics (bk.II: causes, change); Posterior Analytics (bk.I: essential nature, scientific inference); On the Heavens (bk.II: cosmology); On Generation & Corruption (change from Physics examined biologically); Meteorology; On the Universe*; Sense and Sensiblia (perception); On Dreams; History of Animals (zoology pioneering work); Parts of Animals (bk.I: classification of nature & knowledge); On Colours*; etc.

- The Complete Works of Aristotle, Vol. 2, ed. Jonathan Barnes (Princeton UP, 1984), including:

- Metaphysics (bk.XXII: substances’ relations to cosmology); On Plants*; Mechanics* (wheel paradox); On Indivisible Lines*; etc. (*: authorship debated)

- The Essential Epicurus: Letters, Principal Doctrines, Vatican Sayings, and the Fragments, trans. Eugene M. O’Connor (Prometheus Books, 1993)

- Euclid, Euclid's Elements, trans. T.L. Heath (Green Lion 2002)

- (Albertus Magnus, The Commentary of Albertus Magnus on Book 1 of Euclid's Elements of Geometry (Ancient Mediterranean and Medieval Texts and Contexts, Vol. 3), ed. Anthony Lo Bello (Brill, 2003))

- The Works of Archimedes, trans. Sir Thomas Heath (Dover Books on Mathematics, 2002).

- Lucretius, De rerum natura (3 vols. Latin text Books I-VI), trans./comment. Cyril Bailey (Oxford University Press, 1947)

- On the Nature of Things, trans. R. E. Latham (1951), ed. notes by John Godwin (New York: Penguin 1994/2007) OR trans. Walter Englert (Hackett)

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History: A Selection (New York: Penguin, 1991)

- The Almagest: Introduction to the Mathematics of the Heavens, trans. Bruce M. Perry (Green Lion Press, 2014).

- Ptolemy: Tetrabiblos, Loeb Classical Library No. 435, trans. F.E. Robbins (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1940)

- Carmen Astrologicum, trans. David Pingree (Astrology Classics, 2005).

- The Philosophical Works of Al-Kindi, trans. Peter Adamson and Peter E. Pormann (Oxford, OUP, 2012)—all al-kindi works avail. In English trans., including: 3 Texts against the Infinity of the World, On the Quiddity of Sleep and Dreams, 2 Texts on Color, …Generation & Corruption, On the Nature of the Celestial Sphere, On why the ancients related the 5 geometric shapes to the elements, etc.

- The 40 Chapters of Al-Kindi: Traditional Horary & Electional Astrology, trans. Benjamin N. Dykes (Cazimi Press, 2011).

- al-Shifa’ [Cure or The Healing] (encyclopedic collection re: phi. & sci.; books within including: On the Heavens and the Earth (re: rectilinear and circular motion), On Generation and Corruption (re: change in Aristotelian substances), On Actions and Passions (re: bodies affected & affection others, primary qualities hot-cold, wet-dry, etc.), Meteorology (re: inanimate bodies), etc.)

- Incoherence of the Philosophers;

- The Alchemy of Happiness;

- Criterion of Knowledge in the Art of Logic;

- Touchstone of Reasoning in Logic; etc.

- John Duns Scotus, A Treatise on Potency and Act. Questions on the Metaphysics of Aristotle Book IX, Introduction with Latin text and English translation and notes by Allan B. Wolter, OFM, (Franciscan Institute Publications, 2000)

- Scotus, Early Oxford Lecture on Individuation, trans. Allan B. Wolter, OFM (Franciscan Institute Publications, 2005)

- Scotus, Questions on Aristotle's Categories, trans. Lloyd A. Newton (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2014)

- Duns Scotus on Time and Existence: The Questions on Aristotle's 'De interpretatione,' trans. Edward Buckner and Jack Zupko (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2014)

- Ockham’s Theory of Terms: Part I of the Summa Logicae, trans, Michael J. Loux (St. Augustine Press, 2011)

- Ockham’s Theory of Propositions: Part II of the Summa Logicae, trans, Alfred J. Freddoso and Henry Schuurman (St. Augustine Press, 2011)

- Philosophical Writings: A Selection, trans. Philotheus Boehner (Hackett, 1990)

- The Metaphysics and Natural Philosophy of John Buridan (Medieval and Early Modern Science), eds., Thijssen and Zupko (Brill, 2000)

- Zita V. Toth, Buridan’s Physics and/or Experimental Method: The Concept and Role of Experimentum in John Buridan’s Physics Commentary (VDM Verlag Dr Müller, 2010)

- The Logic of John Buridan (Opuscula Graecolatina S.), trans. Jan Pinborg (Museum Tusculanum Press, 1976)

- Later Medieval Metaphysics: Ontology, Language, and Logic (Medieval Philosophy: Texts and Studies, eds. Bolyard and Keele (Fordham UP, 2013)

- On the Revolutions of Heavenly Spheres, trans. Charles Glenn Wallis (Prometheus Books, 1995)

- N. Copernicus, On the Revolutions, trans. E. Rosen (1978)

- Galileo Galilei, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems: Ptolemaic and Copernican, trans. Stillman Drake (Modern Library, 2001)

- (The Sidereal Messenger of Galileo Galilei, and a part of the preface to Kepler’s Dioptrics …, trans. Edward Stafford Carlos; html copy at: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/46036/46036-h/46036-h.htm)

- Mysterium cosmographicum [Sacred Mysteries of the Cosmos] (1596)

- Astronomia nova [New Astronomy] (1609), trans. William H. Donahue (Green Lion Press, 2015).

- Harmonices Mundi [Harmony of the Worlds] (1619)

- Epitome astronomiae Copernicanae [Epitome of Copernican Astronomy] (3 pts., 1618-21)

- Tabulae Rudolphinae [Rudolphine Tables] (1627)

- Somnium [The Dream] (1634)

- Johannes Kepler, Epitome of Copernican Astronomy & Harmonies of the World, trans. trans. Charles Glenn Wallis (Prometheus Books, 1995)

- Johannes Kepler, Optics, trans. William H. Donahue (Green Lion Press, 2000).

- (The Sidereal Messenger of Galileo Galilei, and a part of the preface to Kepler’s Dioptrics …, trans. Edward Stafford Carlos; html copy at: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/46036/46036-h/46036-h.htm)

- (Walter William Bryant, Kepler, at: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Kepler)

- Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica [Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy] (1687, 1713, 1726) (classical mechanic’s laws of motion; gravitation)

- Newton, Newton’s Principia, The Central Argument: Translation, Notes, Expanded Proofs, trans. Dana Densmore, William H. Donahue (Green Lion Press, 2003)

General & Misc. Secondary Texts, Histories, Anthologies, etc.:

|

|

Math:

Hermetica, Alchemy:

- Greek Mathematical Works: Volume I, Thales to Euclid, trans. Ivor Thomas (Loeb Classical Library) (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1939)

- Greek Mathematical Works: Volume II, From Aristarchus to Pappus (Loeb Classical Library No. 362), trans. Ivor Thomas (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1941)

- Sir Thomas Heath, A History of Greek Mathematics, Vol. 1: From Thales to Euclid (Dover, 1981)

- Sr. Mary Leonitius Schulte, Writing the History of Mathematical Notations: 1483-1700 (Docent Press, 2015).

- Serafina Cuomo, Ancient Mathematics (Sciences of Antiquity Series) (Routledge, 2001)

- O. Neugebauer, The Exact Sciences in Antiquity (Dover, 1969) (Babylonian & Egyptian math & astronomy)

- Balaguer, M., 1998. Platonism and Anti-Platonism in Mathematics, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sourcebook in the Mathematics of Medieval Europe and North Africa, eds. Katz, Folkerts, Hughes, etc. (Princeton UP, 2016)

- J. L. Berggren, Episodes in the Mathematics of Medieval Islam (Springer, 2016)

- Robert Goulding, Defending Hypatia: Ramus, Savile, and the Renaissance Rediscovery of Mathematical History (Springer, 2010)

- Robert Sworder, Mathematical Plato (Sophia Perennis, 2013)

Hermetica, Alchemy:

- Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a new English Translation, trans. Brian P. Copenhaver (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1995).

- Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, Occult Philosophy (1997)

- Stanton J. Linden, The Alchemy Reader: From Hermes Trismegistus to Isaac Newton (Cambridge: CUP, 2003)

- Syed Nomanul Haq, Names, Natures and Things: The Alchemists Jabir ibn Hayyan and his Kitab al-Ahjar (Book of Stones), Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1994)–Jabir ibn Hayyan aka Gerber aka Jabir (initial & key Islamic alchemist, methodical rigorous scientification of alchemy)

- Donald Routledge Hill, ‘The Literature of Arabic Alchemy’ in Religion: Learning and Science in the Abbasid Period, ed. by M.J.L. Young, J.D. Latham and R.B. Serjeant (Cambridge University Press, 1990)

- The Arabic Works of Jabir ibn Hayyan, trans. Richard Russel (1678), ed. E.J. Holmyard (New York, E. P. Dutton, 1928)

- The Summa Perfectionis of Pseudo-Geber: A Critical Edition, trans. William R. Newman

- William R. Newman, New Light on the Identity of Geber, Sudhoffs Archiv (1985, Vol.69, pp. 76–90.

|

Medicine:

Optics:

|

Pre-Socratics on Various Sciences:

|

“… It is important for our purposes here to recognize that in the Middle Ages the distinction among the three [sexes] was not just blurred, it did not exist. If someone deviated from the expected models of sexual behavior, people did not assume that the variation was a matter of biology or gender identity or sexual desire; the three worked together . . . For them, sexuality was not separate from sex and gender”

--Ruth Mazo Karras, Sexulaity in Medieval Europe: Doing Unto Others (New York: Routledge, 2005).

“Might it perhaps be wiser in the end not to distinguish between men and women at all?”

--Otto Weininger, Sex and Character, 11.

--Ruth Mazo Karras, Sexulaity in Medieval Europe: Doing Unto Others (New York: Routledge, 2005).

“Might it perhaps be wiser in the end not to distinguish between men and women at all?”

--Otto Weininger, Sex and Character, 11.

VI) Environmental & Philosophy of Nature

Animals:

Environmental Ethics:

Environmental Aesthetics (& Phenomenology):

- Adams, Carol J. and Josephine Donovan (eds.), Animals and Women: Feminist Theoretical Explorations, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995.

- Adams, Carol J. and Lori Gruen (eds.), Ecofeminism: Feminist Intersections with Other Animals and the Earth, New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2014.

- Attenborough, David, The Life of Birds, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998.

- Beauchamp, Tom L. and R.G. Frey (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Animal Ethics, New York: Oxford, 2011.

- Bekoff, Marc and Jessica Pierce, Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- Darwin, Charles, Origin and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009 (anniversary edition).

- Derrida, Jacques, The Animal That Therefore I Am (Animal que donc je suis), Mary-Louise Mallet (ed.) and David Wills (trans.), New York: Fordham University Press, 2008.

- Donaldson, Sue and Will Kymlicka, Zoopolis: A Political Theory of Animal Rights, New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Gruen, Lori, Ethics and Animals: An Introduction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- –––, Entangled Empathy: An Alternative Ethic for Our Relationship with Animals, Brooklyn: Lantern Books, 2015.

- Kheel, Marti, Nature Ethics: An Ecofeminist Perspective, Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2008.

- Lurz, Robert W. (ed.), The Philosophy of Animal Minds, Cambridge UP, 2009, ISBN 9780521711814.

- Midgley, Mary, Animals and Why They Matter, Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1983.

- Osborne, C., Dumb Beasts and Dead Philosophers: Humanity and Humane in Ancient Philosophy and Literature, Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Pollan, Michael, The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals, New York: Penguin Books, 2007.

- Singer, Peter, Animal Liberation, second edition, New York: New York Review of Books, 1990.

- –––, Practical Ethics, second edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; first edition, 1979 [1993].

- –––, “All Animals are Equal”, Philosophic Exchange, 5:1 (1974): Article 6.

- SOPHIA 57 (Special Issue on Animals and Philosophy), 1–4 (2018).

Environmental Ethics:

- Abram, D., The Spell of the Sensuous, New York: Vintage Books, 1996.

- Armstrong, Susan, Richard Botzler, Environmental Ethics: Divergence and Convergence, McGraw-Hill, Inc., New York, New York.

- Belshaw, Christopher, Environmental Philosophy: Reason, Nature and Human Concern, Montreal & Kingston: Mcgill-Queen’s University Press, 2001.

- Benton, Ted, Natural Relations: Ecology, Animal Rights and Social Justice, London: Verso, 1993.

- Callicott, J.B., “Animal Liberation, A Triangular Affair”, reprinted in Callicott, In Defense of the Land Ethic: Essays in Environmental Philosophy, Albany: SUNY Press, 1989, pp. 15–38.

- –––, “Intrinsic Value, Quantum Theory, and Environmental Ethics,” 1985, reprinted in Callicott 1989, pp. 157–74.

- –––, “Animal liberation and Environmental Ethics: Back Together Again,” 1988, reprinted in Callicott 1989, pp. 49–59.

- –––, “The Wilderness Idea Revisited: The Sustainable Development Alternative,” 1991, in J. B. Callicott and M.P. Nelson (eds), The Great New Wilderness Debate, Athens: University of Georgia Press, pp. 337–66.

- –––, Beyond the Land Ethic: More Essays in Environmental Philosophy, Albany: SUNY Press, 1999.

- –––, Thinking Like a Planet: The Land Ethic and Earth Ethic, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Callicott, J. Baird, and Ames, Roger T., Nature in Asian Traditions of Thought, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989.

- Carson, Rachel, Silent Spring, London: Hamish Hamilton, 1963.

- Cheney, J., “Postmodern Environmental Ethics: Ethics as Bioregional Narrative”, Environmental Ethics, 11 (1989): 117–34.

- Cohen, M.P., The Pathless Way: John Muir and American Wilderness, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

- Cronon, William, “The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature,” in Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature, ed. William Cronon (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1995), pp. 69-90.

- Darwin, Charles, Origin and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009 (anniversary edition).

- Devall, B., and Sessions, G., Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered, Salt Lake City: Peregrine Smith, 1985.

- Foltz, Bruce V., Robert Frodeman, Rethinking Nature, Indiana University Press, 2004.

- Fraser, C., Rewilding the World: Dispatches from the Conservation Revolution, New York: Metropolitan Books, 2009.

- Gaard, G. (ed), Ecofeminism: Women, Animals, Nature, Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1993.

- James Garvey, The Ethics of Climate Change: right and wrong in a warming world (London: Continuum, 2009).

- Gruen, L. and Jamieson, D. (eds), Reflecting on Nature, New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Jamieson, Dale, Ethics and the Environment: An Introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

- Keulartz, Jozef, The Struggle for Nature: A Critique of Environmental Philosophy, Routledge, 1999.

- Leopold, Aldo, “The Land Ethic,” in A Sand County Almanac, Ballantine Books, 1986 (7th ed), 237-264.

- Monbiot, G., Feral: Searching for Enchantment on the Frontiers of Rewiilding, London: Allen Lane, 2013.

- Stone, A., “Adorno and the Disenchantment of Nature”, Philosophy and Social Criticism, 32 (2006): 231–253.

- Morton, T., Ecology without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics,Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Muir, J., A Thousand Mile Walk to the Gulf, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1916.

- Oelschlaeger, Max, The Idea of Wilderness: From Prehistory to the Age of Ecology, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

- Regan, T. (ed), Earthbound: New Introductory Essays in Environmental Ethics, New York: Random House

- Rolston III, Holmes, “Duties to Endangered Species,” in Environmental Ethics, ed. Robert Elliot (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 60-75.

- Simmons, J. Aaron, “Evangelical Environmentalism: Oxymoron or Opportunity?” Worldviews 13 (2009): 40-71.

- Zimmerman, M., Contesting Earth’s Future: Radical Ecology and Postmodernity, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1994.

Environmental Aesthetics (& Phenomenology):

- Andrews, M., The Search for the Picturesque, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1989.

- –––, “The View from the Road and the Picturesque,” in The Aesthetics of Human Environments, A. Berleant and A. Carlson (ed.), Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2007.

- Appleton, J., The Experience of Landscape, London: John Wiley and Sons, 1975.

- Arntzen, S. and Brady E., (eds.), Humans in the Land: The Ethics and Aesthetics of the Cultural Landscape, Oslo: Oslo Academic Press, 2008.

- Bannon, B. E., “Re-Envisioning Nature: The Role of Aesthetics in Environmental Ethics,” Environmental Ethics, 33 (2011): 415–436.

- Bryan Bannon (ed.), Experience and Nature: Phenomenology and the Environment, Rowman and Littlefield.

- Bartalesi, L. and Portera M., “Beyond the Nature-Culture Dichotomy: A Proposal for Evolutionary Aesthetics,” Aisthesis, 8 (2015): 101–111.

- Bell, S., Landscape: Pattern, Perception and Process, London: Routledge, 1999.

- Berleant, A., “Aesthetic Paradigms for an Urban Ecology,” Diogenes, 103 (1978): l–28.

- –––, “Aesthetic Participation and the Urban Environment,” Urban Resources, 1 (1984): 37–42.

- –––, “Toward a Phenomenological Aesthetics of Environment,” in Descriptions, H. Silverman and D. Idhe (ed.), Albany: SUNY Press, 1985.

- –––, “Cultivating an Urban Aesthetic,” Diogenes, 136 (1986): 1–18.

- –––, “Environment as an Aesthetic Paradigm,” Dialectics and Humanism, 15 (1988): 95–106.

- –––, The Aesthetics of Environment, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992.

- –––, Living in the Landscape: Toward an Aesthetics of Environment, Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1997.

- –––, Aesthetics and Environment: Variations on a Theme, Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005.

- –––, “Reconsidering Scenic Beauty,” Environmental Values, 19 (2010): 335–350.

- –––, “Ideas for an Ecological Aesthetics,” in Ecological Aesthetics and Ecological Assessment and Planning, X. Cheng, A., Berleant, P. Gobster, and X. Wang (eds.), Zhengzhou: Henan People’s Press, 2013.

- –––, “What is Aesthetic Engagement?” Contemporary Aesthetics, 11 (2013) [available online].

- –––, “Some Questions for Ecological Aesthetics,” Environmental Philosophy, 13 (2016): 123–135

- ––– and Carlson, A., (eds.), The Aesthetics of Human Environments, Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2007.

- Biese, A., The Development of the Feeling for Nature in the Middle Ages and Modern Times, New York: Burt Franklin, 1905.

- Bourassa, S. C., The Aesthetics of Landscape, London: Belhaven, 1991.

- Brady, E., “Imagination and the Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 56 (1998): 139–147.

- –––, Aesthetics of the Natural Environment, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003.

- Budd, M., The Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Carlson, A., “Environmental Aesthetics and the Dilemma of Aesthetic Education,” Journal of Aesthetic Education, 10 (1976): 69–82.

- –––, “On the Possibility of Quantifying Scenic Beauty,” Landscape Planning, 4 (1977): 131–172.

- –––, “Appreciation and the Natural Environment,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 37 (1979): 267–276.

- –––, “Nature, Aesthetic Judgment, and Objectivity,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 40 (1981): 15–27.

- –––, “Nature and Positive Aesthetics,” Environmental Ethics, 6 (1984): 5–34.

- –––, “On Appreciating Agricultural Landscapes,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 43 (1985): 301–312.

- –––, “Is Environmental Art an Aesthetic Affront to Nature?” Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 16 (1986): 635–650.

- –––, “On the Aesthetic Appreciation of Japanese Gardens,” British Journal of Aesthetics, 37 (1997): 47–56.

- –––, Aesthetics and the Environment: The Appreciation of Nature, Art and Architecture, London: Routledge, 2000.

- –––, Nature and Landscape: An Introduction to Environmental Aesthetics, New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

- Cooper, David, A Philosophy of Gardens, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Drenthen, M. and Keulartz, J., (eds.), Environmental Aesthetics: Crossing Divides and Breaking Ground, New York: Fordham University Press, 2014.

- Heidegger, Martin, “A Question Concerning Technology,” in Basic Writings, ed. David Farrell Krell (New York: HaperCollins, 1993), 308-341 and “Building Dwelling Thinking,” Ibid., 344-363.

- Hepburn, Ronald, “Contemporary Aesthetics and the Neglect of Natural Beauty,” in The Aesthetics of Natural Environments, ed. Allen Carlson and Arnold Berleant, Toronto: Broadview Press Ltd., 2004, 43-62.

- ----, “Landscape and the Metaphysical Imagination,” in Ibid., 127-140.

- Herrington, S., On Landscapes, London: Routledge, 2009.

- Jóhannesdóttir, G. R., “Phenomenological Aesthetics of Landscape and Beauty,” in Nature and Experience: Phenomenology and the Environment, B. E. Bannon (ed.), Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2016.

- Kemal, S. and Gaskell, I., (eds.), Landscape, Natural Beauty and the Arts, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Klaus Carl, ed., Herbarium (New York: Parkstone Press, 2011)—plates from Hortus Eystettensis of Basilius Besler, 1613.

- Miller, M., The Garden As Art, Albany: SUNY Press, 1993.

- Moore, R., Natural Beauty: A Theory of Aesthetics Beyond the Arts, Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2008.

- Nasar, J. L., (ed.), Environmental Aesthetics: Theory, Research, and Applications, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Nguyen, A. M., (ed.), New Essays in Japanese Aesthetics, Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2018.

- Nicolson, M. H., Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1959.

- Oudolf, Piet and Darke, Rick, Gardens of the High Line: Elevating the Nature of Modern Landscapes, Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2017.

- Parsons, G., Aesthetics and Nature, London: Continuum Press, 2008.

- Porteous, D. J., Environmental Aesthetics: Ideas, Politics and Planning, London: Routledge, 1996.

- Ross, S., “Gardens, Earthworks, and Environmental Art,” in Landscape, Natural Beauty and the Arts, S. Kemal and I. Gaskell (ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- –––, What Gardens Mean, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

- Sepänmaa, Y., The Beauty of Environment: A General Model for Environmental Aesthetics, Second Edition, Denton: Environmental Ethics Books, 1993.

- Francis Bacon, “XXXVIII: Of Nature in Men,” in Essays, Civil and Moral (The Harvard Classics: 1909–14; New York: P. F. Collier & Son, 1937).

- Margret Berger, ed., Hildegard of Bingen: On Natural Philosophy and Medicine: Selections from Cause et Cure (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1999).

- Joseph A. Cocannouer, Weeds: Guardians of the Soil (Old Greenwich, CN: The Devin-Adair Co., 1950, 1980).

- William Coles, The Art of Simpling: An introduction to the Knowledge and Gathering of Plants, (Pomeroy, WA: Health Research Books, 1986)—a reprint of that printed in London by J. G. for Nath: Brook, 1656.

- Rachel Carson, Silent Spring, New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2002 (anniversary reprint).

- ----, The Sense of Wonder: A Celebration of Nature for Parents and Children, New York: Harper Perennial, 2017 (reprint).

- Edward S. Casey, “Taking a Glance at the Environment: Prolegomena to an Ethics of the Environment,” Research in Phenomenology, 31 (2001): 1-21.

- Forrest Clingerman, “The Intimate Distance of Herons: Theological Travels through Nature, Place, and Migration,” in Ethics, Place & Environment 11, 3 (Oct. 2008): 313-325.

- ----, and Mark H. Dixon (eds.), Placing Nature on the Borders of Religion, Philosophy and Ethics (Surrey, United Kingdom: Ashgate Publishers, August 2011). ISBN: 978-1-4094-2044-6. Available Here.

- Anne Ophelia Dowden, Wild Green Things in the City: A Book of Weeds (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1972).

- Nina Edwards, Weeds (London: Reaktion Books LTD, 2015).

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The Fortune of the Republic,” §XXX., 1-76 marginal pagination, in Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882): The Complete Works, Vol. XI, Miscellanies (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006).

- Nicholas Everett, ed., The Alphabet of Galen: Pharmacy from Antiquity to the Middle Ages (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012).

- Gail Harland, The Weeder’s Digest: Identifying and Enjoying Edible Weeds (Totnes, Devon, England: Green Books, 2012).

- Robert Pogue Harrison, “On the Lost Art of Seeing,” in Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition, 114-124.

- Alice Henkel, Weeds Used in Medicine, U. S. Department of Agriculture, Farmers’ Bulletin No.188 (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1917), digitized by the Missouri Botanical Garden, available ~~here~~.

- Carl G. Jung, “We Have Conquered Nature is a Mere Slogan,” in The Earth has a Soul: C.G. Jung on Nature, Technology & Modern Life, ed. Meredith Sabini (Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2008), 121-135.

- Richard Mabey, Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants (New York: Harper-Collins, 2010). Available ~~HERE~~.

- Richard Mabey, The Cabaret of Plants: Forty Thousand Years of Plant Life and the Human Imagination (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2015). Available ~~HERE~~.

- Michael Pollan, Second Nature: A Gardener’s Education (New York: Grove Press, 1991).

- Gareth Richards, Weeds: The Beauty and Uses of 50 Vagabond Plants (London: Royal Horticultural Society and Welbeck Publishing Group, 2021).

- John Charles Ryan, Plants in Contemporary Poetry: Ecocritism and the Botanical Imagination (New York: Routledge, 2018).

- Huron H. Smith, Ethnobotany of the Menomini Indians (Westport, CN: Greenwood Press, 1923, reprint 1970).

- ----, Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians (Milwaukee, WI: Order of the Board of Trustees, Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee, 1932).

- Gary Snyder, “Earth Day and the War Against the Imagination,” in A Place in Space, 56-64.

- Malcolm Stuart, ed., The Encyclopedia of Herbs and Herbalism (London: Orbis Publishing, 1979).

- Douglas W. Tallamy, Bringing Nature Home: How you can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants (Portland: Timber Press, 2009). Available ~~HERE~~.

- Douglas W. Tallamy, The Nature of Oaks: The Rich Ecology of Our Most Essential Native Trees (Portland: Timber Press, 2021). Available ~~HERE~~.

- Henry David Thoreau, “Walking,” in Natural History Essays (Salt Lake City, UT: Peregrine Smith Books, 1980), 93-136.

- Lynn White, Jr., The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis (with discussion of St. Francis; reprint, 1967), in Ecology and Religion in History (New York: Harper and Row, 1974), 211-218.

- Ken Thompson, The Book of Weeds: How to Deal with Plants that Behave Badly (London: DK Books, 2009).

- Anne Van Arsdall, ed., A New Translation of the Old English Herbarium (New York: Routledge, 2002).

VII) Gender Studies:

Gender &/Or/Vs. Sex (Biological, Psychological, Marxist, Phenomenological, Existential, etc. Attempts to define what it is):

Socio-Political Constructions/Consequences Gender/Sex, Sexuality Politics, Body Politics:

Contemporary Socio-Political/Identity Issues/Queer Studies: (many of these less philosophical proper, more in sociological, lit. theory, cultural studies, etc. veins)

Feminist Theory Types of & Evaluation: (cf. “Classic,” below, for “1st wave” & “Psycho/French,” below, for 3rd wave)

Classic Phi. Works on Gender/Sex/Sexuality/Political and Works Thereupon:

Psychoanalytic Analyses of Gender/French Feminism:

Men’s Studies/Masculinity/Masculine Domination/Misogyny:

Gender and Popular Culture, Film, Sports, Education, Society, etc.:

Philo-Literary Accounts, Gender Relations:

- Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, pp.3-37 (critique of biological account); pp.38-60, pp.139-98, pp.253-71, 328-36, 371-403 (embodiment theory).

- Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity

- ---. Bodies that Matter

- ---. Undoing Gender

- Aristotle, On the Generation of Animals, Book I, chs. 2-22, Book II, chs. 1-5.

- Otto Weininger, Sex and Character, pp.5-44 (VERY weird Biological account; spectrum of gender predating trans movement).

- Elizabeth Grosz, “Refiguring Bodies,” Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism,” pp.3-24 (embodiment theory).

- Linda Alcoff, The Identity Crisis in Feminist Theory

- Alphonso Lingus, Libido: The French Existential Theories, “Libido and Alterity,” pp.103-20.

- Anne Fausto-Sterling, Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality (Basic Books, 2000)

- Emily Martin, “The Egg and the Sperm,” pp.10-15.

- Kathryn Ringrose, “Byzantine Medical Lore and the Gendering of Eunuchs,” pp.15-20.

- Nelly Oudshoorn, “Sex and the Body,” pp.6-9.

- Noretta Koertge, “How Might we put Gender Politics into Science?”

- Helen E. Longino, “Taking Gender Seriously in Philosophy of Science.”

- Judith Lorber, “Believing is Seeing: Biology as Ideology,” pp.13-26.

- Plato, “Aristophanes’ Speech in Praise of Love,” Symposium, pp.1-3 (embodiment theory).

Socio-Political Constructions/Consequences Gender/Sex, Sexuality Politics, Body Politics:

- Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1, 2, or 3 (intellectually rigorous, theoretical account of said)

- Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, trans. H. M. Parshley (New York: Vintage, 1989), isbn: 9780679724513, list price: $17.95

- Hélène Cixous and Catherine Clément, The Newly Born Woman, trans. Betsy Wing (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986), isbn: 978-0816614660.

- Sander Gilman, The Jew’s Body (on using physical traits to judge character and as a weapon of discrimination)

- Londa Schiebinger, Nature’s Body: Gender in the Making of Modern Science (how sexual roles influenced development of modern science from botany to Linneaus’ taxonomy, study of apes, to 18th c.)

- John Boswell, Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality (historical account of Church’s acceptance of homosexuality from founding to the 14th c. through its literature and records)

- John D’Emilio, Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America (cultural account of sexuality as constantly remade over history between puritanical and hedonistic poles)

- Rosemary Salomone, Same, Different, Equal: Rethinking Single-Sex Schooling

- Aldo Carotenuto, “The Sacredness of the Body,” Eros and Pathos: Shades of Love and Suffering, trans. Charles Nopar, pp.51-8.

- Alphonso Lingus, Libido: The French Existential Theories, “Libido and Alterity,” pp.103-20.

- Robert Baker, “‘Pricks’ and ‘Chicks’: A Plea for ‘Persons’,” pp.143-50.

- Kathryn Woodward, “Concepts of Identity and Difference,” pp.195-7.

- Judith Butler, Gender Trouble, “Subjects of Sex/Gender/Desire,” pp.1-46.

- Catharine A. MacKinnon, Toward a Feminist Theory of the State (MA: Harvard UP, 1991) (Jurisprudence)

- ---. Feminism Unmodified (MA: Harvard UP, 1988) (collection essays, rape, sexual harassment, pornography)

- Angela Davis, Women, Race, and Class (NY:Vintage, 1983).

- Friedrich Engels, The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State

- Nancy C. M. Hartstock, Developing the Ground for a Specifically Feminist Historical Materialism

- Heidi Hartman, Towards a More Progressive Union (critique of Marxist base feminism)

- Elsa Barkley Brown, The Politics of Difference in Women’s History and Feminist Politics

- The UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights (www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/index.shtml).

Contemporary Socio-Political/Identity Issues/Queer Studies: (many of these less philosophical proper, more in sociological, lit. theory, cultural studies, etc. veins)

- Monique Wittig, The Straight Mind: And Other Essays (Beacon Press, 1992) (women’s struggles for lib from sexism classism)

- Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks

- Michael Warner, The Trouble with Normal: Sex, Politics, and the Ethics of Queer Life (MA: Harvard UP, 1999)

- Judith Halberstam, Female Masculinity (Duke UP, 1998)

- Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Crossing Press, 2007)

- Edward W. Said, Orientalism (NY: Vintage, 1979) (Outsider Studies, Muslim Orient stereotypes)

- José Esteban Munoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (U of Minnesota P, 1999)

- Bell Hooks, Feminist Theory from Margin to Center (NY: Routledge, 2014)

- Riki Wilchins, Queer Theory, Gender Theory: An Instant Primer (Riverdale Avenue Books, 2014)

- Chandra Talpade Mohanty, Feminism without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity

- Lauren Berlant & Lee Edelman, Sex, or the Unberable (Theory Q) (dialogue, contradictions raised by Queer Theory, works via culture, lit, art)

- Annamarie Jagose, Queer Theory (attempt to define it, move from homosexuality to fluid ideas of sexual identity)

- William B. Turner, A Genealogy of Queer Theory (queer theory roots in outsiderness of identity, works from Foucualt)

- Lee Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (attempt at an ethic of Q theory, works from Freud)

- Sara Ahmed, Queer phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, and Others (incorporate phen as method for Q theory)

- Elizabeth Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (temporal and sexual dissonance, how history can be embodied and erotic, via art culture studies)

- Adrienne Rich, Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence

Feminist Theory Types of & Evaluation: (cf. “Classic,” below, for “1st wave” & “Psycho/French,” below, for 3rd wave)

- Elizabeth Grosz, Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism (gender, race, and sex as lived experience)

- Judith Butler, Bodies that Matter, “Introduction,” pp.1-23.

- Linda Martín Alcoff, “The Identity Crisis in Feminist Theory,” Visible Identities: Race, Gender, and the Self, pp.133-50.

- Nancy Fraser, On Discourse Theory and Feminist Politics

- Bell Hooks, “Black Women: Shaping Feminist Theory”, reader

- ---. Feminist Theory from Margin to Center (NY: Routledge, 2014)

- Harvey C. Mansfield, “A New Feminism,” pp.1-7.

- Jean-François Lyotard, “One of the Things at Stake in Women’s Struggles,” pp.9-17.

- Anna Quindlen, “Women Are Just Better,” Living out Loud, pp.27-9.

- Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique (2nd wave)

- Gloria Steinem, Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions (2nd wave)

- Kate Millett, Sexual Politics (U of IL Press, 2000) (2nd wave fem.—uses cultural discourse, lit, etc.)

- Shulamith Firestone, The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution (NY: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2003) (2nd wave fem)

- Germaine Greer, The Female Eunuch (2nd wave fem, women’s lib)

- Linda Nicholson, The Second Wave: A Reader in Feminist Theory (Routledge, 1997)

- Nancy C. M. Hartstock, Developing the Ground for a Specifically Feminist Historical Materialism

- Heidi Hartman, Towards a More Progressive Union (critique of Marxist base feminism)

Classic Phi. Works on Gender/Sex/Sexuality/Political and Works Thereupon:

- Aristotle’s Politics, Bk. I, Chs. I-XIII (available at: http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/politics.1.one.html).

- Plato’s Phaedrus (dialogue on love & speeches/writing; available at: http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/phaedrus.html).

- Luce Irigaray, “The Wedding between the Body and Language” in To Be Two, “Sorcerer Love: A Reading of Plato, Symposium, ‘Diotima’s Speech,’” in An Ethics of Sexual Difference –related: Eleanor H. Kuykendall, “Introduction to ‘Sorcerer Love: A Reading of Plato’ by Luce Irigaray,” in Revaluing French Feminism

- Tales of the Titans, Prometheus, and Persephone, Favorite Greek Myths, pp.1-12.

- Elizabeth Cody Stanton, “The Book of Genesis,” The Woman’s Bible, pp. 14-9.

- Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex,

- Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

- Estelle Freedman, ed., The Essential Feminist Reader (good collection of historical works on feminism)

- Miriam Schneir, Feminism: The Essential Historical Writings (collection of historical works on feminism)

- Alice S. Rossi, ed., The Feminist Papers: From Adams to Beauvoir (NorthEastern UP, 1988) (collection of historical works on feminism)

Psychoanalytic Analyses of Gender/French Feminism:

- Sigmund Freud, The Ego and the Id.

- ---. “V. The Material and Sources of Dreams, D. Typical Dreams,” The Interpretation of Dreams, pp.1-22.

- ---. “The Development of the Libido and the Sexual Organizations,” Lecture XXI, A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis, pp.1-10.

- ---. “Contribution III: The Transformations of Puberty,” in Three Contributions to the Theory of Sex, pp.1-15.

- ---. “Some Psychological Consequences of the Anatomical Distinction between the Sexes,” Homburg International Psycho-Analytical Congress (1925), pp.1-9.

- ---. “Female Sexuality,” trans. Joan Riviere, Int. J. Psyco-Alal. 13 (1932): 281; pp.1-12.

- Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of …: On Feminine Sexuality, the Limits of Love and Knowledge, trans. Bruce Fink (NY: W. W. Norton & Co., 1999).

- Elizabeth Grosz, “Masculine and Feminine,” Volatile Bodies: Towards a Corporeal Feminism, pp.57-61 (Freud vs. Lacan on sexual development of the genders).

- Irigaray, “This Sex which is not One”, in This Sex Which is not One

- ––. Je, tu, nous: Toward a Culture of Difference (Routledge, 1992), isbn: 978-0415905824.

- ––. Speculum of the Other Woman (Cornell UP, 1985).

- ––. An Ethics of Sexual Difference (Cornell UP, 1993).

- ––. The Way of Love (Bloomsbury Academic, 2002).

- Judith Butler, “Melancholy Gender/Refused Identification,” in The Psychic Life of Power, ch 5 (text itself includes work on Hegel, Niet., Freud, Foucault, Althusser).

- ––. Undoing Gender (Routledge, 2004).

- Julia Kristeva, Strangers to Ourselves, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (Columbia UP, 1994).

- ––. Revolution in Poetic Language, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (Columbia UP, 1984).

- ––. Power of Horror: An Essay of Abjection (Columbia UP, 1982).

- ––. Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art, trans. Thomas Gora and Alice A. Jardine (Columbia UP, 1980).

- Kelly Oliver, Witnessing: Beyond Recognition (Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 2001), isbn: 978-0816636280.

- ––. Subjectivity without Subjects: From Abject Fathers to Desiring Mothers (Rowman & Littlefield, 1998).

- Georges Bataille, Eroticism: Death and Sensuality, trans. Mary Dalwood (San Francisco: City Lights, 1986).

- Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism & Schizophrenia (NY: Penguin, 2009).

- ––. Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism & Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 1987).

- Jacques Derrida, Spurs: Nietzsche’s Styles (Chicago UP, 1981).

- Carl Gustav Jung, Aspects of the Masculine / Aspects of the Feminine (Stereotype/Gender as Archetype).

- Joseph Campbell, “Woman as the Temptress,” pp.120-6, “The Virgin Birth,” pp.297-314—both in Hero with a Thousand Faces (Stereotype/Gender as Archetype).

- Bly, “I Came Out of the Mother Naked,” in Sleepers Joining Hands, pp.29-50 (Stereotype/Gender as Archetype).

- Lévi-Strauss, “Structural Analysis in Linguistics and in Anthropology,” pp.1-7; “The Structural Study of Myth,” pp.1-5—both in Structural Anthropology (Stereotype/Gender as Archetype).

- Chodorow, “Gender, Relation and Difference in Psychoanalytic Perspective”, Meyers text

- Alsop, Fitzsimons and Lennon, eds. Theorizing Gender: An Introduction, “Bodily Imaginaries” (ch. 7) (Quasi text book).

- Weedon, Feminist Practice and Poststructuralist Theory, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996 (text book)

- Nancy J. Chodorow, Feminism and Psychoanalytic Theory, Yale Univ. Press, 1991.

- Linda M. G. Zerilli, Feminism and the Abyss of Freedom (problem of subjectivity)

- Kelly Ives, Julia Kristeva: Art, Love, Melancholy, Philosophy, Semiotics and Psychoanalysis, Cresent Moon Publishing, 2015 (French Feminism & Kristeva, Feminism in art).

- ––. Cixous, Irigaray, Kristeva: The Jouissance of French Feminism (Crescent Moon Pub., 2015), isbn: 978-1861714206.

- The Kristeva Reader, eds. Julia Kristeva and Toril Moi, (Columbia Univ. Press, 1986)–esp. ch.II on women, psychoanalysis, politics.

- The Irigaray Reader, ed. Margaret Whitford (Wiley-Blackwell, 1992) isbn: 978-0631170433.

- French Feminism Reader, ed. Kelly Oliver (Roman & Littlefield, 2000), isbn: 978-0847697670.

- New French Feminisms: An Anthology, ed. Elaine Marks (U. of Mass. Press, 1979), isbn: 978-0870232800.

- Language and Liberation: Feminism, Philosophy, and Language, eds. Christina Hendricks and Kelly Oliver (NY: SUNY Press, 1999).

- Deleuze and Feminist Theory, eds. Ian Buchanan and Claire Colebrook

Men’s Studies/Masculinity/Masculine Domination/Misogyny:

- Robert Bly, Iron John (founding work of Men’s Studies and the “Expressive Men’s Movement”)

- Robert Bly, Sleepers Joining Hands (New York: HarperCollins, 1991), isbn: 0060907851.

- R. W. Connell, Masculinities (more sociological, ties masculine to social inequity)

- Michael Kimmel, The Gendered Society (more sociological, social construction of gender, men & women)

- Pierre Bourdieu, Masculine Domination (study of masculine domination as pervasive and often unrecognized throughout culture, esp. symbolic violence in everyday life and its institutions)

- Friedrich Nietzsche, The Genealogy of Morals, esp. Essay III.

- Jacques Derrida, Spurs (postmod., on Nietzsche’s complex stance (praising, misogynistic, chauvinistic) on women)

- Luce Irigaray, Marine Lover (re: Nietzsche)

- Nietzsche, Feminism, and Political Theory, ed. Paul Patton (Routledge)

- Feminist Interpretations of Friedrich Nietzsche, eds. Kelly Oliver and Marilyn Pearsall

- Klaus Theweleit, Male Fantasies, Vol. 1-2 (study of self and sexual identity and fascist male desire of post-WWI German Freikorps who became central to Hitler’s army)

- Catharine A. MacKinnon, Women’s Lives, Men’s Laws

- Rosi Braidotti,

Gender and Popular Culture, Film, Sports, Education, Society, etc.:

- Harry Benshoff, America on Film: Representing Race, Class, Gender, and Sexuality at the Movies

- E. Ann Kaplan, Feminism and Film

- Robert Baker, “‘Pricks’ and ‘Chicks’: A Plea for ‘Persons’,” pp.143-50.

- Michele Morris, “Olympic Gender Discrimination,” pp.1-2.

- Elizabeth Meyer, “Olympics and Gender Empowerment Through Sport,” pp.1-3.

- Katherine Franke, “Running Like a Girl: Sex-Stereotyping in the Olympics,” pp.1-3.

- Cynthia Nantais and Martha F. Lee, “Women in the United States Military: Protectors or Protected? The Case of Prisoner of War Melissa Rathbun-Nealy,” pp.181-91.

- Stephen Kershnar, “For Discrimination against Women,” pp.589-625.

- David B. Cruz, “Disestablishing Sex and Gender,” pp.997-1086.

Philo-Literary Accounts, Gender Relations:

- Jean Paul Sartre, “The Room” (available at: http://faculty.risd.edu/dkeefer/pod/wall.pdf).

- Kierkegaard’s “Seducer’s Diary” in Either/Or (available at: http://www.mediafire.com/?9pdpnp4f7uppdz4).

- Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals, Essay Three.

- Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

|

“For a woman to (re)discover herself could only signify, then, the possibility of not sacrificing any of her pleasures to an other, of not identifying herself with anyone in particular, of never being simply one … which for all that would not be incoherence” --Irigaray, This Sex Which is Not One, 166. |

VIII) Gender Studies Films:

- -- Alain Berliner’s “Ma vie en rose” (French, 1997).

- -- David Cronenberg’s “M. Butterfly” (Canadian, 1993), “Spider” (2002).

- -- Peter Howitt’s “Sliding Doors” (British, 1998).

- -- Woody Allen’s “Love and Death” (American, 1975), “Annie Hall” (1977), “A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy” (1982), “Alice” (1990), “Husbands and Wives” (1992), “Vicky Cristina Barcelona” (2008).

- -- Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s “The Marriage of Maria Braun” (German, 1979).

- -- David Lynch’s “Lost Highway” (American, 1997), “Inland Empire” (2006).

- -- Khyentse Norbu’s “Travellers and Magicians” (Bhutanese, 2003).

- -- Alain Resnais’ “Last Year at Marienbad” (French, 1962).

- -- Harmony Korine’s “Mister Lonely” (American, 2007).

- -- Hiroshi Teshigahara’s “Face of Another” (Japanese, 1952).

celebrations as pausings, permitting a

“passing over into the more wakeful intimation of wonder”

--Martin Heidegger, Hölderlin’s Hymn “Remembrance,”

trans. William McNeill & Julia Ireland (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2018), p.58.

trans. William McNeill & Julia Ireland (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2018), p.58.

IX) P h i l o s o p h i c a l F i l m s

~ Experimental ~

~ Art-House ~ Delightful ~ Intellectually Provocative ~

~ Touch of Magic & Surreal ~ Whimsical to Macabre ~

~ Strange ~ Surreal ~ Eerily Dark ~

~ Existential ~ Soulfully Striking ~ Unhurried ~

- Stan Bralhage’s “By Brakhage: An Anthology,” (American, experimental shorts from 1954-2001), either volume.

- Godfrey Reggio’s ‘Qatsi Trilogy’ (American, artistic-environmental documentaries): “Koyaanisqatsi” (1983), “Powaqqatsi” (‘88), “Naqoyqatsi” (2002).

- Hiroshi Teshigahara’s “Antonio Gaudí” (Japanese, doc. on the architect, 1984).

- Jean Painlevé’s “Science is Fiction: 23 Films” (French, artful science films, 1925-82), any two shorts.

- Chantal Akerman’s “Hotel Monterey” (Belgium-Amer., ‘architectural mediation,’ 1972).

- Andrei Tarkovsky’s “Stalker” (Russian, metaphy. journey, ‘79).

~ Art-House ~ Delightful ~ Intellectually Provocative ~

- Woody Allen’s “Annie Hall” (America, 1977), “Interiors” (‘78), “Midnight in Paris” (‘11).

- Harmony Korine’s “Mister Lonely” (American, 2007).

- Whit Stillman’s “Metropolitan” (American, 1990), “Barcelona” (‘94), “Last Days of Disco” (‘98).

- Abbas Kiarostami’s “Certified Copy” (Iranian, but film in French, 2010).

- Éric Rohmer’s “My Night at Maud’s (French, 1969), “Claire’s Knee” (‘70), “La collectionneuse” (‘67).

- Jean-Luc Godard’s “A Woman is a Woman” (French, 1961), “Tout Va Bien” (‘72), “Breathless” (‘60).

- Federico Fellini’s “8 ½” (Italian, 1963).

- François Truffaut’s “Jules and Jim” (French, 1961).