Kant's Critique [of the Power of] Judgment

I) On Kant:

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804):

Born in Königsberg (capital of the province of East Prussia, it later became part of Germany and is today in Russia; he is considered a German philosopher). He never really left, traveling no more than forty or so miles from his birthplace (he turned down teaching positions so not to have to leave). Born into a poor family, he lost both his parents while he was still relatively young.

His educational upbringing was by the Pietists, a Protestant (Lutheran) sect that changed the focus from church ritual to personal piety emphasizing strict devotion; it ultimately turned Kant away from any practice of religion (his moral and religious writings were banned for a number of years during his life).

Although, like the religion, his life is also characterized as strict, secluded, and predictable; neighbors were said to set their watches by his daily walk. He never married and reputedly never engaged in any other comforts of women. And, despite his treatise on art remaining the pallbearer of theory today, his actual exposure to artworks is severely limited.

At ten, he studied theology at the Collegium Fredericianum, and excelled at classics. At 16, he entered the University of Könisberg to study mathematics and physics; he was introduced to rationalist philosophy and Newtonian physics, influencing his critique of traditional idealism and creation of a “transcendental idealism.” He became an expert in the physical sciences and mathematics and made impressive contributions to nearly every field of philosophy (from metaphysics to ethics to aesthetics to education to law to history… etc.). He was employed as a private tutor for nine years then lectures for 15 years as a Privatdozent (a non-salaried instructor).

At 45 years old (1770), he was appointed Professor of Logic and Metaphysics at the University of Königsberg. He produced a number of early works on diverse topics, a number of them scientific, but none are regarded with much attention today.

II) On Kant’s Philosophy

Kant’s invaluable contribution to Western Philosophy is his Critical Project :

- His initial question, in his Critique of Pure Reason (written in 1781 and revised in 1787), is whether metaphysics is possible, which is to ask, are a priori synthetic judgments valid?

- This work of epistemology 'solves' the (esp.) early modern question of the origin of knowledge as from experience or reason by elaborating a system of their synthesis.

- His second work is his Critique of Practical Reason (1788) and represents his application of his examination of reason to the practical realm: ethics.

- His Deontological Meta-ethics: morality is formed from a rational foundation called the “Categorical Imperative,” which is a rational, universal, duty-based demand deducible by the mind alone; morality is obedience to this imperative while immorality violates it and is, thus, irrational. It is duty-based in that moral content is not chosen by potential consequences (i.e., we are not nice to our siblings in order to get a cookie and avoid being sent to our room; instead, we are nice because it is universally, rationally, morally right, thus, it is our moral duty).

- There are three formulations of the Categorical Imperative:

- 1) Act on the maxim that you will to be a universal law (i.e., act in such a way as if the maxim that guides your action will become a universal law of nature).

- 2) Act so that you treat all humanity always as an end and never merely as a means.

- 3) Act as if you were a law-making member of a universal kingdom of ends (i.e., a hypothetical perfect, moral society, and our goal to create).

- There are three formulations of the Categorical Imperative:

- His Deontological Meta-ethics: morality is formed from a rational foundation called the “Categorical Imperative,” which is a rational, universal, duty-based demand deducible by the mind alone; morality is obedience to this imperative while immorality violates it and is, thus, irrational. It is duty-based in that moral content is not chosen by potential consequences (i.e., we are not nice to our siblings in order to get a cookie and avoid being sent to our room; instead, we are nice because it is universally, rationally, morally right, thus, it is our moral duty).

- His Third Critique is his Critique of the Power of Judgment (1790), about aesthetics and teleology.

- His aesthetics divide the Beautiful from the Sublime; the former is judged by four conditions: Disinterest, Universality, Purposiveness without purpose, and Necessity. The Sublime is that experience wherein our ability to intuit is overwhelmed by magnitude or force; we then conquer over the sublime when we can think it. The second half of his work is concerned with teleology (the study of ends, goals).

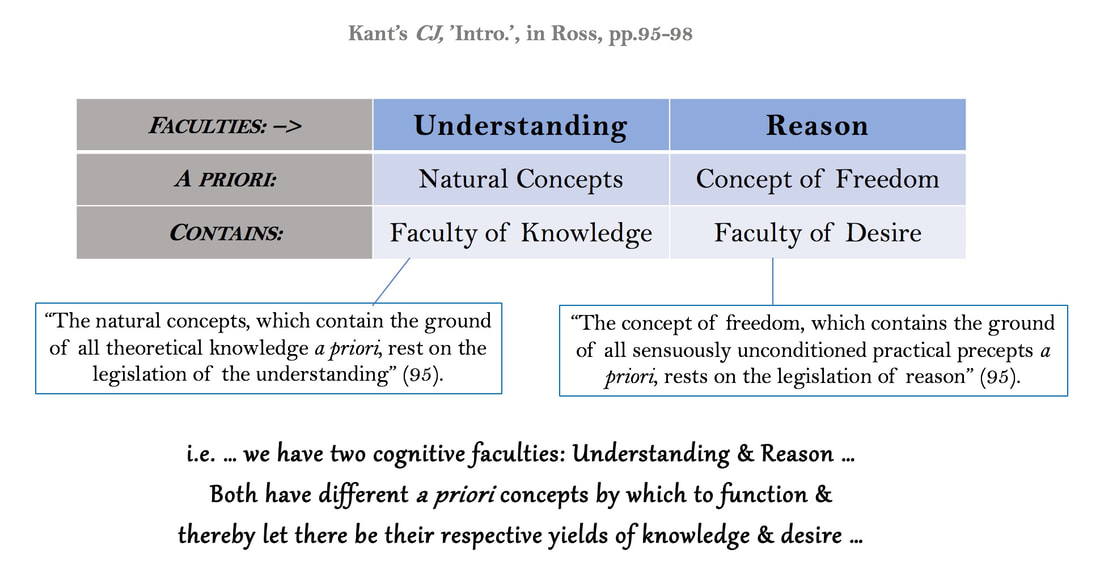

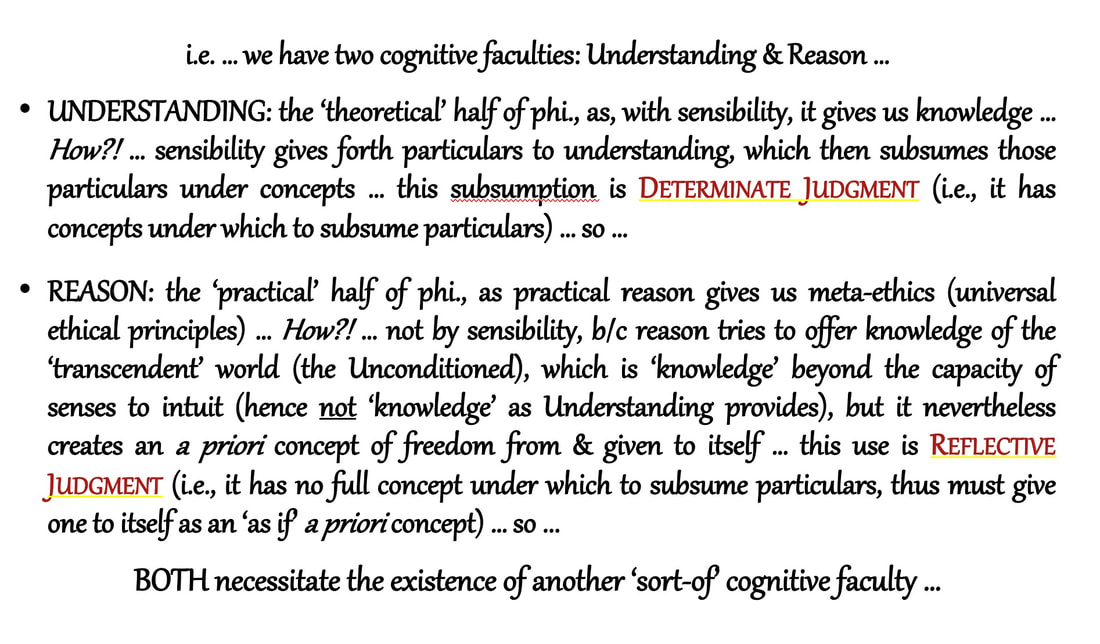

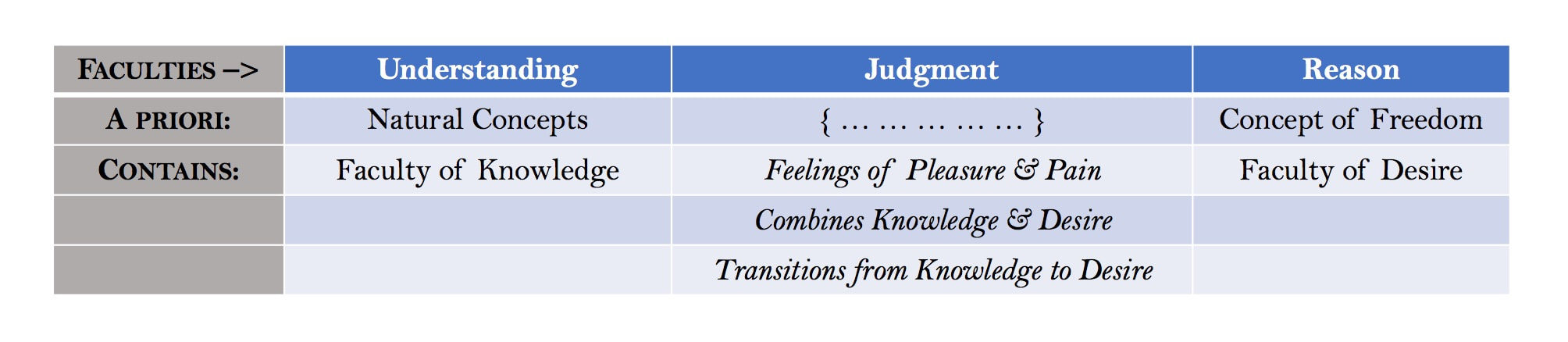

The hinge of these three works is his metaphysical stance on Reason … his epistemology, more properly, the faculty of judgment.

- In Understanding, judgments are determinate (has concept to subsume particulars under).

- In Reason, judgments are reflective (has no full concept).

So, how does Judgment judge without a concept? Does Reflective Judgment give itself an a priori principle? YES—it gives itself an a priori principle via Reason of the Purposiveness of Nature, which can be represented via Aesthetic or Teleological Judgments.

- Aesthetic Judgments: Accordance of Form (related by imagination) to the Cognitive Faculties; Form is considered a ground of pleasure from the representation.

- Teleological Judgments: Accordance of Form with the possibility of the thing-itself; the Thing is represented by form to be fulfilling an End or Purpose of nature.

The a priori regulative concept of the Purposiveness of Nature connects nature (1st Critique) with freedom (2nd Critique).

... i.e.:

III) On The Critique [of the Power] of Judgment:

[Read in Conjunction with Kant’s “Introduction,” in Ross, pp.95-8]

The German title of Kant’s work is Kritik Der Urteilskraft. This is typically translated into English as The Critique of Judgment, although a more accurate translation is Critique of the Power of Judgment. The word “Urteil” is judgment, and “skraft” designates the faculty of judgment conceived of as a power (a power we have to make judgments). “Skraft” is an unique word choice; it is different from the German word Macht, which also translates as power, and is the term the (infamous) slightly later German philosopher Nietzsche uses when discussing human faculties as powers. Kant’s Critique of the Power of Judgment is often referred to as “the Third Critique,” because it was the third in his “critical project,” a series of texts described above.

The full contents of the “Third Critique” are as follows:

As you can see from this, the Critique of Judgment divides into two main parts, one on aesthetics and one on teleology (the study of telos, of ends, final causes, or aims), and it is, as its title says, a critique as an exploration of the limits and sources of judgment. More specifically, it is exploring what a priori principles (principles known through pure reason, that is, before experience) might lie in our ability to judge things? These a priori principles would thus be the transcendental conditions for that ability (that is, they would be the utterly foundational and necessary conditions for the ability to be).

Judgment is a coordinating faculty—it literally serves to coordinate things—it receives concepts from some cognitive faculty and applies those concepts to other cognitive faculties--e.g., scientific judgments receive concepts from understanding and applies them to sensibility; moral judgments receive concept from practical reason (“virtue” or “guilt”) and apply them to some particular instance in experience. Judgment is nearly synonymous with what we call ‘thinking’ in everyday parlance.* In the introduction (see p. 95 in the Ross anthology), Kant expresses this by saying: “But in the family of supreme cognitive faculties there is a middle term between the understanding and the reason. This is the judgment …” (95).

In the 3rd Critique, Kant focuses on two types of judgment: aesthetic and teleological. These two types are distinctive from all others by being “REFLECTIVE.” This means that a determining concept (which accords with the principles of the understanding) NEVER enters the equation in these two types of judgments.

Note the utter importance of this and the seeming absurdity—Kant is undertaking a critique (an exploration of the limits and sources of something) of two types of judgment that are reflective. Reflective judgments have no concepts, but judgment, as explained above precisely serves to coordinate concepts between faculties. So, how do you coordinate concepts if you have no concepts? Said in a more Kantian way: if judgment is the subsumption of particulars under concepts (e.g., sensibility gives data through space and time to understanding, which then applies to it the categories (i.e., quality, quantity, relation, modality), and thus “thinks” the object), how exactly is judgment going to work if there are NO appropriate concepts by which to ‘organize’ the data?

[Read in Conjunction with Kant’s “Introduction,” in Ross, pp.95-8]

The German title of Kant’s work is Kritik Der Urteilskraft. This is typically translated into English as The Critique of Judgment, although a more accurate translation is Critique of the Power of Judgment. The word “Urteil” is judgment, and “skraft” designates the faculty of judgment conceived of as a power (a power we have to make judgments). “Skraft” is an unique word choice; it is different from the German word Macht, which also translates as power, and is the term the (infamous) slightly later German philosopher Nietzsche uses when discussing human faculties as powers. Kant’s Critique of the Power of Judgment is often referred to as “the Third Critique,” because it was the third in his “critical project,” a series of texts described above.

The full contents of the “Third Critique” are as follows:

- Preface

- Introduction

- Critique of the Aesthetic power of Judgment

- Analytic of the Beautiful (§1-22)

- Analytic of the Sublime (§23-29)

- Deduction of Pure Aesthetic Judgments (§30-54)

- The Dialectic of the Aesthetic power of Judgment (§55-60)

- (appendix) On the Methodology of Taste (§60)

- Critique of the Teleological Power of Judgment (§61)

- Analytic of the teleological Power of Judgment (§62-8)

- Dialectic of the Teleological Power of Judgment (§69-78)

- (appendix) Methodology of the Teleological Power of Judgment (§79-91)

As you can see from this, the Critique of Judgment divides into two main parts, one on aesthetics and one on teleology (the study of telos, of ends, final causes, or aims), and it is, as its title says, a critique as an exploration of the limits and sources of judgment. More specifically, it is exploring what a priori principles (principles known through pure reason, that is, before experience) might lie in our ability to judge things? These a priori principles would thus be the transcendental conditions for that ability (that is, they would be the utterly foundational and necessary conditions for the ability to be).

Judgment is a coordinating faculty—it literally serves to coordinate things—it receives concepts from some cognitive faculty and applies those concepts to other cognitive faculties--e.g., scientific judgments receive concepts from understanding and applies them to sensibility; moral judgments receive concept from practical reason (“virtue” or “guilt”) and apply them to some particular instance in experience. Judgment is nearly synonymous with what we call ‘thinking’ in everyday parlance.* In the introduction (see p. 95 in the Ross anthology), Kant expresses this by saying: “But in the family of supreme cognitive faculties there is a middle term between the understanding and the reason. This is the judgment …” (95).

- * : In everyday speech, we typically use “thinking” to mean what Kant means by “judgment”--a coordination of the given under the category of their 'what-ness'--however, these terms are not universally equated, near synonymous, or roughly defined as such in and across philosophy. In particular, the later German phenomenological philosopher Martin Heidegger wished to keep thinking separate from judgment—he felt they were importantly distinct and that it was the freer, more creative thinking to which we ought to pay attention.

In the 3rd Critique, Kant focuses on two types of judgment: aesthetic and teleological. These two types are distinctive from all others by being “REFLECTIVE.” This means that a determining concept (which accords with the principles of the understanding) NEVER enters the equation in these two types of judgments.

Note the utter importance of this and the seeming absurdity—Kant is undertaking a critique (an exploration of the limits and sources of something) of two types of judgment that are reflective. Reflective judgments have no concepts, but judgment, as explained above precisely serves to coordinate concepts between faculties. So, how do you coordinate concepts if you have no concepts? Said in a more Kantian way: if judgment is the subsumption of particulars under concepts (e.g., sensibility gives data through space and time to understanding, which then applies to it the categories (i.e., quality, quantity, relation, modality), and thus “thinks” the object), how exactly is judgment going to work if there are NO appropriate concepts by which to ‘organize’ the data?

Balthasar van der Ast, Still Life with Basket of Fruit

Balthasar van der Ast, Still Life with Basket of Fruit

Said in a less Kantian way: imagine that you have a basket full of apples, oranges, grapes, and bananas … your judgment needs to take all the data these things give you (color, shape, etc.) and figure out what they are … understanding can use categories to figure these out (how many, what relation to one another, etc.), but, a reflective judgment has no concepts … so, it is like judging this basket of things without having the idea of “fruit,” or “food,” or “round things,” etc.

Our anthology does not include the following, but I think it may help to understand the differences between judgments, to see how aesthetic ones are unique, and to show how he helps to address this seeming absurdity … Thus, Kant, in his full introduction, roughly distinguishes five types of judgments:

- (1) Determinate Judgment: consists of the application of a concept (well-known and general) to a given situation or object. This is a question of seeing if the given particular matches up with our concept of it. The concept determines the thing as this or that. Through the concept, the determination has validity beyond the precise situation in which it is formed. Other people can come along and use the same concept to judge whether or not my judgment was correct.

- (2) Indeterminate Judgment: here, the situation or object is new to me and I have no concept of it in advance. Therefore, I must come up with a new concept about it in order to perform the judgment. As we saw in the 1st Critique, in the Transcendental Analytic, that we cannot attain knowledge without the principled application of the transcendental concepts like unity, cause, effect, necessity, etc. Thus, when we try to understand anything in the world, we use these concepts, but they are very general, and we can come across very particular things that do not fall exactly in complete detail beneath these concepts. Therefore, we have to form empirical concepts about these things in the course of ordinary experience. This is indeterminate judgments, it discovers new concepts. Like the determinate judgment, the indeterminate will have a wide range of validity.

- (3) Teleological Judgment: we come across some things that are multiplicities of functions that work together as a whole—think of any organism with a heart, lungs, muscles, etc.—and it seems that the whole organism was “designed” as an elaborate active structure for creating and sustaining the whole. Seeing organisms in this way, is a teleological judgment—seeing them as “caused” by their telos (purpose), the completed and whole form. So, the teleological judgment happens when we judge something to have been produced according to an idea of it, but where this judgment is at odds with the way that object is “natural” and determinately judged. This has an important, but limited range of validity. (This is similar to being an extreme version of the indeterminate judgment).

- (4) Aesthetic Judgment: here, we do not have a concept in advance, and yet, the situation is such that I also MUST JUDGE WITHOUT forming a new concept. In order to form a judgment, I am thrown back entirely to my own resources as a thinking subject. This is similar to an extreme version of the indeterminate judgment. These judgments are about things we call Beautiful or Sublime. Now, IF I did have a concept of beautiful or great or horrible, etc., I would be able to give a rigorous account of criteria with which everyone could agree. This is not the case, obviously, with art. My judgments about beauty do not follow or produce a concept, but take place by way of FEELING—specifically, the feeling of pleasure in the beautiful. Although subjective, these judgments have a wide range of validity.

- (5) Judgments of Sensual Interest: here, we have an extreme version of the aesthetic in a sense. This is like an absolute subjectivism, where my taste in a non-aesthetic category (food, wine, etc.) can be entirely my own, can change over time, etc.. This sort of judgment, although entirely subjective, does not cause philosophical problems because we are okay with saying that agreeable and disagreeable tastes can be fluid and personal. The validity of the judgment belongs uniquely to the person who makes it.

Thus … we see that aesthetic judgments (as do teleological judgments), as reflective judgments, give themselves an a priori principle via Reason of the Purposiveness of Nature. (On page 97 ff. of the anthology, we see purposiveness broached.)

Thus, one of the key questions in the text will concern understanding what is the purposiveness without purpose? (Equally important, and related, will be how aesthetic judgments can be subjective and universal at the same time, which allows Kant to move into the important more general question, albeit rather implicit, of how judgment may serve as the mediator between the subject matter of the 1st and 2nd Critiques, thus unifying philosophy).

Why does he attempt to do the seemingly absurd investigation into judgment that happens minus concepts? He is asking: does judgment have a legislative principle within itself? In undertaking the task, he asserts a belief in the suitability or purposiveness of nature for our faculty of judgment. If judgment had no principle within itself, then, first, science would be impossible—an unified, systematic concept of nature would be impossible; and second, judgments of the beautiful would neither be universal nor would they be communicable. The study of aesthetic judgment, then, may provide the best case (as it is more common than teleological judgments) to prove the a priori to be truly a priori and grounded within the human subject, and thus capable of unifying all branches of philosophy.

Thus, with this background, let us turn to aesthetics and to the text:

IV) Textual Analysis:

On The Analytic of the Beautiful

(cf., Ross, pp.98-113)

[Read in Conjunction with Kant’s “First Book: Analytic of the Beautiful,” in Ross, pp.98-113]

Aesthetics …

comes from the Greek verb aisthesthai, “to perceive;” it is the study of art and beauty. It asks questions like: what is the beautiful? Is there universal beauty, or is all beauty relative? How do we judge beauty? Are judgments of taste universal? What is art? Who makes art, the genius or anyone/thing? What is the difference between beauty and the sublime? Etc.

How Taste Differs …

Kant divides Faculties of Cognition from the Faculties of Desire. The former judge knowledge through understanding; the latter judge beauty through the feeling of pleasure or pain.

Typically, to know X we refer its representation to the Object through Understanding (does ‘representation X’ match ‘object X’?). However, to judge beauty, we refer the representation to the subject through Imagination (does ‘representation X’ provoke pleasure?)

“The judgment of taste is therefore not a judgment of cognition, and is consequently not logical but aesthetical, by which we understand that whose determining ground can be no other than subjective” (Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, Analytic of the Beautiful, §1. Note: I will quote several different translations, but all will be quite similar; here, for Ross, see page 98).

A subjective ground, however, does not mean that taste is relative!

A Quick Overview of the Next Five Upcoming Sections:

Note that these five sections fall under the subheading “First Moment: Of the Judgment of Taste, According to Quality;” note, further, that the Analytic of the Beautiful (pp.98-113) is made up of four moments. Each of these moments relate to the categories Quality, Quantity, Relation, and Modality. If you have read Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, (or Aristotle’s Physics) you recognize these as “The Categories.” If you are not familiar with the others, just note that these are four distinct but interrelated moments (i.e., four important considerations or points) about the judgment of taste.

- §1 explains how the judgment of taste is aesthetical (Ross, p.98).

- §2 explains how the satisfaction that this judgment of taste yields (when this judgment is of the beautiful) must be disinterested (Ross, pp.98-9).

- §3 explains how the satisfaction yielded from the judgment of the pleasant is bound up with interest (Ross, pp.99-100).

- §4 explains how the satisfaction yielded from the judgment of the good is bound up with interest (Ross, pp.100-01).

- §5 compares these three judgments of taste: the beautiful, the pleasant, and the good (Ross, 102-3).

Now … Detail about these Five Sections:

The Beautiful, Pleasant, and Good:

In aesthetic judgments, we can judge that a thing is: Beautiful, Pleasant, or Good.

“The Pleasant, the Beautiful, and the Good, designate then, three different relations of representations to the feeling of pleasure and pain … . That which gratifies a man is called pleasant; that which merely pleases him is beautiful; that which is esteemed [or approved] by him, i.e. that to which he accords an objective worth, is good” (CJ, §5).

Beautiful………………mere pleasure…………… we judge it disinterestedly

Pleasant…………………pleasure as gratification……………we judge it to satisfy our wants

Good…………………pleasure as esteem………………we judge it to be useful

Only Judgments of the Beautiful are disinterested, that is, they are judged without bias. Thus, the art object, in the sense of a true masterpiece, must be judged as Beautiful, not Pleasant or Good.

In aesthetic judgments, we can judge that a thing is: Beautiful, Pleasant, or Good.

“The Pleasant, the Beautiful, and the Good, designate then, three different relations of representations to the feeling of pleasure and pain … . That which gratifies a man is called pleasant; that which merely pleases him is beautiful; that which is esteemed [or approved] by him, i.e. that to which he accords an objective worth, is good” (CJ, §5).

Beautiful………………mere pleasure…………… we judge it disinterestedly

Pleasant…………………pleasure as gratification……………we judge it to satisfy our wants

Good…………………pleasure as esteem………………we judge it to be useful

Only Judgments of the Beautiful are disinterested, that is, they are judged without bias. Thus, the art object, in the sense of a true masterpiece, must be judged as Beautiful, not Pleasant or Good.

The Good:

Shovels in the garage or a coat peg by the back door are “good,” that is, they are good for something: they are useful.

Shovels in the garage or a coat peg by the back door are “good,” that is, they are good for something: they are useful.

“In order to find something good, I must always know what sort of thing the object is supposed to be, i.e., I must have a concept of it”

--Kant, CJ, §4.

Things judged to be Good please, predominately as a means for us to accomplish some end. I know what the snow shovel is and what it can do: it clears snow from my path. (And, it pleases me that there is such a thing I can use to clear away the snow.) I know what a coat peg is, and what it can be used for, for hanging up my coat. (Likewise, it pleases me that there is such a thing that can neatly hold my coat.) The good pleases by fact of its practicality.

The other variation of “good,” for Kant, is that which is good in itself. This type of good also has an end, but is not necessarily a means, for example, humanity, God, or justice. Each of these more abstract things please for themselves: our satisfaction from them is in and by the fact of their existence (CJ, §4).

- Now, a great challenge to Kant’s conception of the Good is the “Readymade.” As the name suggests, this is a class of art made up of found objects. The greatest examples of readymades come from Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), the French artist connected to the schools of Dada and Surrealism (and with a background in symbolism (eschewing realism for the privilege of metaphoric meaning, e.g., Odilion Redon and Böcklin, cubism (the ‘geometrization’ of figure, e.g., Picasso and Braque), and fauvism (in which color is elevated over representation, e.g., Matisse, Derain, and Braque). Duchamp famously provoked the public and art world to (re)consider what is art. Many of his “readymades” (first produced ca. early 1900s) were found art in its most basic sense: “Fountain” (1917) was literally an urinal, “Hat Rack,” was a coat peg, and “Bottle Rack” (1914), was precisely that, a rack for drying bottles. Other readymades developed the idea of found art to add artifice to the everyday object, for example, his “Bicycle Wheel” (1913) was a wooden stool with bicycle wheel sprouting from the seat.

- (If interested, the Kant scholar Thierry de Duve has written a superb book entitled Kant After Duchamp (MIT/October Books, 1998), all about how the Readymades challenged Kantian aesthetics.)

Jasper Johns, Flag,

1954-55

Jasper Johns, Flag,

1954-55

Beyond the readymade, also consider Jasper Johns’ “Flag” (1954-55). Jasper Johns (b. 1930), the American painter and printmaker, does not work in the vein of Dada readymades like Duchamp (despite being often, oddly, described as a Neo-Dadaist), but, his flag paintings do share this same spirit of making a non-art-object into art. His “Flag” (1954-55) was done with encaustic, oil, and collage on fabric then mounted on plywood; he did many variations of the flag.

Are these examples beautiful? We equate the beautiful being the judgment of what is art; thus, to ask if they can be beautiful, we are essentially asking if they can be art? In the readymades or the flags, we have a concept of these things; we know what they are and what they are used for; this suggests that they are merely “good,” and not “beautiful.”

- In contrast to Kant, Duchamp writes:

- “The creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act”

- (Marcel Duchamp, “Session on the Creative Act,” Convention of the American Federation of Arts, Houston, Texas, April 1957).

- “The creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act”

- Against Kant, Duchamp is advocating that to bring interest to the art is not to render it Good or Pleasant, but to help make it Beautiful. He does not want us to use the shovel, but that we must bring forth its idea of use in order to “get” that it is not to be used, that it is a work of art.

The Pleasant:

Food on the table, when I have hunger, stimulation of the nose or taste buds by exotic spices, or the calming pureness of a pale shade of blue are all agreeable, that is, they are Pleasant. The pleasant seeks/yields enjoyment. The starving person does not approach food without interest, nor does the person out for fun approach a game lackadaisically. Thus, concerning representations of agreeableness or pleasantness, we do not approach disinterestedly, but with great interest in the thing’s existence. Pleasantness is related wholly to gratification and inclination. We, the subjects, are drawn inextricably to the object. Our interest here, as with all interest, presupposes or creates a need. This is its relation with the faculty of desire. Desire is universal amongst all animals (not just humans), yet the decision concerning pleasantness is private. In regard to the pleasant, we can say that each has his/her own taste (CJ, §§3-5, 7).

Food on the table, when I have hunger, stimulation of the nose or taste buds by exotic spices, or the calming pureness of a pale shade of blue are all agreeable, that is, they are Pleasant. The pleasant seeks/yields enjoyment. The starving person does not approach food without interest, nor does the person out for fun approach a game lackadaisically. Thus, concerning representations of agreeableness or pleasantness, we do not approach disinterestedly, but with great interest in the thing’s existence. Pleasantness is related wholly to gratification and inclination. We, the subjects, are drawn inextricably to the object. Our interest here, as with all interest, presupposes or creates a need. This is its relation with the faculty of desire. Desire is universal amongst all animals (not just humans), yet the decision concerning pleasantness is private. In regard to the pleasant, we can say that each has his/her own taste (CJ, §§3-5, 7).

Still-lifes of food? If the still-lifes of food are evocative of hunger and you seek them seeking to quench hunger, than they are Pleasant. Anything to gratify needs qualifies for Pleasant.

- e.g.: Luis Egidio Meléndez (1716-1780) Spanish painter; known for his still-lifes, especially their composition and use of light. Jan Davidsz. De Heem (aka Jan Davidszoon de Heem) (1606-1684), Dutch, still life painter:

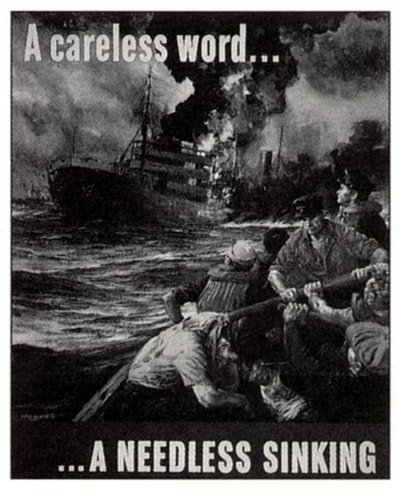

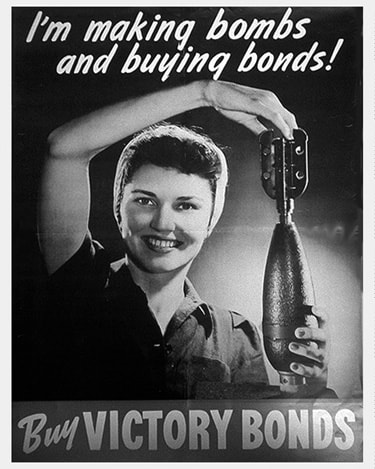

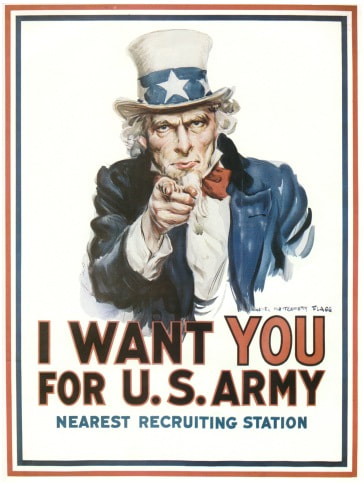

Propaganda Posters? This one is more challenging… propaganda is useful, so that would make it Good; but, if the representations lead to a sense of gratification, makes us feel useful or strong or proud, then it would be Pleasant; and, in the case of the German poster, if we cannot read it [With our Flags is our Victory] or if we did not know what it meant or did, etc., could it be Beautiful?

The Beautiful:

The Beautiful must be approached disinterestedly, that is, without bias (without concern for utility or gratification). This is the opposite aim from the propaganda posters! The Beautiful promises us only pleasure.

There are three further traits that must be satisfied for judgments of beauty. Thus, the Four Moments of the Judgment of Taste of the Beautiful are:

-disinterest,

-subjective,

-universally communicable,

-and have purposiveness without a purpose.

“It is as though in aesthetic judgment we are grasping with our hands

some object we cannot see, not because we need to use it

but simply to revel in its general graspability…”

(Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic (Oxford: Blackwell, 1990), 86).

For Kant, the beautiful includes:

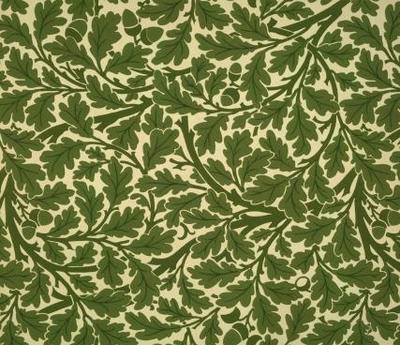

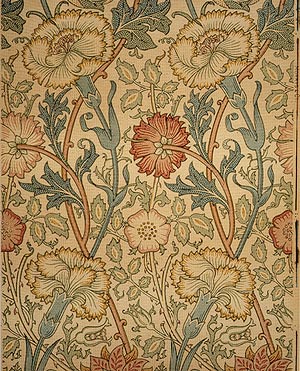

“Flowers, free designs,

lines aimlessly intertwined in each other

under the name of foliage,”

these things “signify nothing,

do not depend on any determinate concept,

and yet please.” (CJ, §4).

To find things to be beautiful, I need neither to have a concept of them nor to know what they are in advance. The beautiful pleases for itself (CJ, §23).

The Beautiful must be approached disinterestedly, that is, without bias (without concern for utility or gratification). This is the opposite aim from the propaganda posters! The Beautiful promises us only pleasure.

There are three further traits that must be satisfied for judgments of beauty. Thus, the Four Moments of the Judgment of Taste of the Beautiful are:

-disinterest,

-subjective,

-universally communicable,

-and have purposiveness without a purpose.

“It is as though in aesthetic judgment we are grasping with our hands

some object we cannot see, not because we need to use it

but simply to revel in its general graspability…”

(Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic (Oxford: Blackwell, 1990), 86).

For Kant, the beautiful includes:

“Flowers, free designs,

lines aimlessly intertwined in each other

under the name of foliage,”

these things “signify nothing,

do not depend on any determinate concept,

and yet please.” (CJ, §4).

To find things to be beautiful, I need neither to have a concept of them nor to know what they are in advance. The beautiful pleases for itself (CJ, §23).

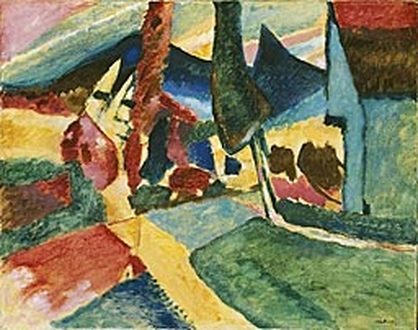

Examples of 'The Beautiful'

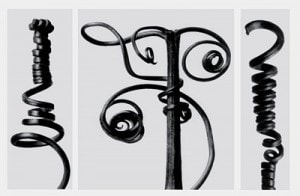

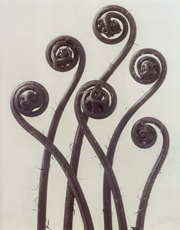

(1) William Morris, “Oak,” Victoria and Albert Museum, “Pink and Rose,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, ca. 1890

(2) Karl Blossfeldt (1865-1932), German photographer and sculptor (iron casting). He is most known for his artful, b&w extreme close-ups of plants collected in his Unformen der Kunst [Artforms in Nature] in 1928. Later editions (unknown of original) has a brief and impressive preface by Georges Bataille in an uncharacteristic piece on the language of flowers. His photographs most remarkably capture form in its purity, originality. His other famous work is Wundergarten der Natur [Magic Garden of Nature]. Originally, the photographs were instructional guides for his students of sculpture to see examples of organic form (cf.: http://www.soulcatcherstudio.com/exhibitions/blossfeldt/).

More (questionable?) Examples (??) of 'The Beautiful'

(3) Mark Rothko (Marcus Rothkowitz, 1903-1970) Latvian-born, American Abstract Expressionist painter. Likened his and other modern art’s primitive style to the art of children, noting that its root is in color and is led by feeling, non-intellectual experience [i.e., a step in development of color field painting]. His interests were in form, space, and color. His art was also led by his social-political life being a Jewish immigrant, studying under Max Weber and Arshile Gorky, and reading Freud, Jung, and Nietzsche (Birth of Tragedy; the last three of which emphasized myth and art). His art trajectory moved from a highly mythically-led surrealism to highly abstract paintings based on color—the critics call the latter “multiform.” For Rothko, color had meaning and was a powerful human expression (breath, life force), even as it lacked mythic symbol or landscape or figure. The size of his latest works (rectangles of color) was massive, meant to overwhelm the viewer and draw him/her within them (encouraged the viewer to stand within 18 inches of them to be therein ‘enveloped’ into the unknown—this culmination can be seen in the Rothko Chapel in Houston)

Below: (left) Orange and Tan, 1949 and (right) Untitled, 1949

Below: (left) Orange and Tan, 1949 and (right) Untitled, 1949

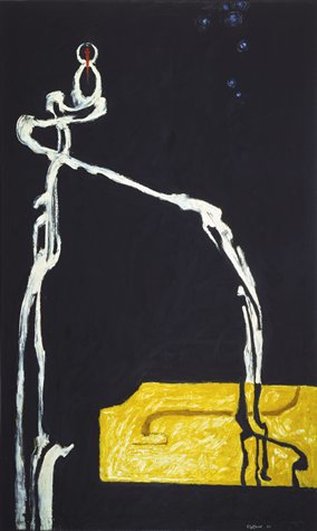

(4) Barnett Newman, Stations of the Cross, 1 (Barnett Newman (1905-1970), NYC, Jewish son of immigrant parents from Russian Poland; Abstract Expressionist and Color Field painter who studied philosophy at CUNY and wrote as much art criticism and organized many exhibitions as he did paint. We painters, he declared, make the world in our own image. His painting style began in surrealism and developed and ended in color field painting. His color field works were unique being mostly solid canvasses with lines of color that he calls “Zips,” running down or across them. Like Rothko’s color fields, these works are mostly massive, typically over eight feet tall and some as large as 28 feet x nine feet (cf., “Anna’s Light,” 1968, painted for his mother’s death). Some are very vibrant in color, for example his series entitled “Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue,” while some very muted, such as “The Stations of the Cross” works. Unlike Rothko and Still, his works do not show brushwork and other humanly touches, but are sleek and minimalist.

These paintings are of particular interest to philosophers like Jean-François Lyotard in that they capture time in the painting … physically, often the actual construction of the lines was a dramatic zipping down tapes, while after, their viewing suggests a quick rupture across a space. Lyotard’s The Inhuman has two very accessible essays that consider his “zips” as instants of time.

(Cf., The Stations of the Cross: Lema sabachthani [why have you forsaken me?] (1958-66) a series of 14 monochromatic paintings he executed after recovering from a heart attack).

(5) Clyfford Still (1904-1980) American Abstract Expressionist and Color Field painter; friends with Rothko. He moved back and forth across the country, born in ND, spent childhood in WA and Canada’s west coast, worked and lived in CA (met Rothko at Berkeley), also lived in NY, taught in Richmond, VA. The Met, in 1979, hosted the largest exhibit to a living artist for his work. Denver was awarded his estate, and the city plans to open a museum for him in 2010. His work bears a similarity to Rothko and Newman, but, unlike the former, his color is more harsh and energetic and, unlike the latter, his lines are more jagged and do not “zip” with a clean modernism, but tear, rip, and pull their color from the canvas (cf.: The Clyfford Still Museum for more).

Right: Clyfford Still, “Untitled [formerly, Self-Portrait],” 1945

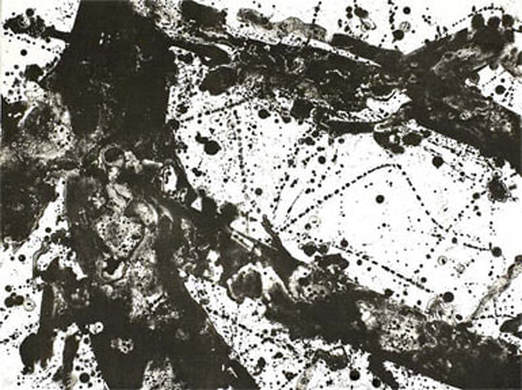

(6) Sam Francis (1923-1994) American painter and printmaker; California school of Abstract Expressionists (sometimes also lumped into Color Field painting). Got into painting and printmaking when he returned injured from WWII, where he served in the Air Force. Traveled to Paris in the 1950’s, where he had his first exhibition in1952, then Japan, where he became heavily influenced by Zen. Until shortly before his death when he completed over 150 small works (his last year his hands were mostly paralyzed because of cancer advancement), his canvasses were massive.

- Lyotard was enthralled with Francis’ works, as well, writing the most poetic work of “art criticism” on him in his book entitled Sam Francis: Like Paintings by a Blind Man…. (with original, art-book printing by Lapis Press, here). He was particularly interested in Francis’ use of white space and how it expressed something unpresented. Francis, himself, also remarked that “I paint time,” which Lyotard would have been caught up by (Jeffrey Perkin, film: The Painter Sam Francis).

- For more, see his website and the Sam Francis Foundation

Below: Sam Francis, “Long Blue,” 1964

Now that we have puzzled through the distinctions between the Good, Pleasant/Agreeable, and the Beautiful, we have to further pursue:

- What are the requirements of this judgment of taste (the judgment of the beautiful)?

- How do we make this judgment?

The Four Moments of the Judgment of Taste of the Beautiful

Each moment is a “rule” we must abide in order to make the judgment as to whether something is beautiful.

The Four Moments are:

- Disinterest

- Universality

- Purposiveness without Purpose

- Necessity (“Common Sense”)

To judge whether is work is beautiful, we refer to the representation of it for the subject through imagination (not to the object for cognition via understanding) (§1). This means that aesthetic judgment is subjective--but this does not mean it is relative (i.e. beauty is not in the eye of the radically isolated beholder; subjects judge, we each do it personally, but there is a universality to which each appeals). What guides our judgment is the sensation of pleasure or pain:

“Here the representation is altogether referred to the subject and to its feeling of life, under the name of the feeling of pleasure or pain”

--Kant, CJ, §1.

But ... this pleasure or pain is not interested (if it was, we would be making a judgment of the pleasant, and maybe the good, not the beautiful). So ... the judgment of the beautiful must be disinterested (the 1st moment). Interest connects to the existence of a thing; in judging the beautiful, I am not concerned with existence (e.g., when looking at a beautiful painting of a landscape, I am not concerned as to whether it actually exists in reality, that does not affect my aesthetic judgment of it).

Because I take no interest in the representation (I am not concerned if it exists, whether it would fit, if I can use it for anything, whether I could eat it, etc.), there is no personal contingency of my judgment--in no way does the judgment hinge on me being me; it could be you, him, anyone making it. So ... the judgment of the beautiful is universal (the 2nd moment) (§6).

Again, if my judgment concerned the actual existence of thing, I would know the thing had a purpose--i.e., it was an effect from a cause. And, “... the causality of a concept in respect of its object is its purposiveness” (§10). There can be (and must be) purposiveness, but it need not have an actual purpose. “The faculty of desire, so far as it is determinable to act only through concepts, i.e., in conformity with the representation of a purpose, would be the will” (§10). How would you get desire to manifest in action if it didn’t suppose some concept? You wouldn’t get up to make coffee when you wanted it if you could not call to mind the idea of drinking coffee! “But an object, or a state of mind, or even an action is called purposive, although its possibility does not necessarily presuppose the representation of a purpose ...” (§10). Remember that aesthetic judgments are not concerned with actual existence, so there is no presumption of the thing represented having an actual purpose. So, in aesthetic judgments, we must presume purposiveness without purpose (the 3rd moment).

Finally, re-raising the second moment’s revelation of universality, Kant elucidates how there is a “common sense,” literally, a sense that all humans have in common, which is especially seen in aesthetics. This leads him to argue how aesthetic judgment is necessary (the 4th moment). This last moment thereby sums up all the prior moments.

Another important aspect to note about these “Four Moments” is that they correspond to the “Four Categories:”

Disinterest ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... Quality

Universality ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... Quantity

Purposiveness without Purpose ... ... ... ... Relation

Necessity and Common Sense ... ... ... ... Modality

Quality, Quantity, Relation, and Modality are the four main divisions of the Table of Categories in Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (each also has three subcategories); they are the “concepts” through which we “think,” that is, these are the concepts from reason to which the representations of sensible data from experience are applied in order for us to have knowledge. Labeling the four moments of the judgment of the beautiful in this way allows Kant to offer an analogy for how these moments are going to “become” our “concept” that aesthetic judgments lack, but need, in order to judge at all.

Now ... let’s delineate these “Four Moments:”

Disinterest

We judge the beautiful by a disinterested satisfaction or dissatisfaction:

Disinterest

We judge the beautiful by a disinterested satisfaction or dissatisfaction:

|

“Interest” is a satisfaction taken in an object and representation of its existence (i.e., in contrast to how aesthetical judgments concern the feeling in a subject, “interest” concerns something in the object itself, specifically, that the thing exists. To attribute existence to something implies that we seek use from it or gratification by it). Interest is partial; in contrast, a pure judgment of taste has no interest, but only mere satisfaction.

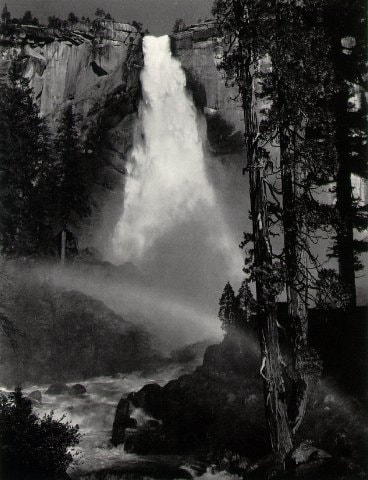

Thus, when we judge something to be beautiful, we cannot be concerned with determining or presuming its existence. If I am looking at a picture of a waterfall, to judge it aesthetically as beautiful, I cannot consider whether or not the waterfall exists in reality, where it exists, whether I could raft over it in a wooden barrel. Further, I cannot say that Goya’s oil on plaster, “Saturn Devouring his Son” (1820-23) is not art (i.e., not beautiful) because Saturn does not exist, nor did he ever devour his son; to do so, I would be judging his painting with interest. |

Universality

We expect all humans who judge correctly to agree with our correct judgment that something is beautiful; this is a demand of agreement, but also a presumption we make in order to judge thus:

Remember that how we determine whether or not we have judged the beautiful correctly is whether we resultantly feel a sense of “mere pleasure.” Pleasure seems private; it seems to us in the everyday to be a wholly subjective, personal, private response, and therefore, this mistaken presumption of privacy makes us jump to the assumption that taste differs. But, we need to understand the nuance; consider the following two claims:

“I like coffee” -- here, we assume privacy: not all agree

“Coffee is bitter” -- here, we assume all to agree (you know this because you, personally, have tasted it and discerned its bitterness, but you assume that you are just detecting something to which all would agree; you can like the bitter or not like it, that makes no difference, but someone else would not correctly say, “no, coffee is salty”)

Judgments of the Beautiful are like the claim “coffee is bitter” -- the judgment of taste behaves as if judgment were a real, objective property of the thing judged, thus universal.

Purposive without a Purpose

The represented object must be understood as purposive (having a finality), but without having an objective or determinate purpose (end):

First, let’s better understand “Purpose” and “Purposiveness” in their most general sense: My purpose is to have a cup of coffee. In order to have this purpose, I must know the object of my intent (desire): “cup of coffee” (I cannot want what I cannot know, I cannot go get X if I do not know what X is). So, first, I conjure up a concept of “cup of coffee,” then, I go about all the steps needed to get that cup of coffee. Now, “purposiveness” is a property the object (the cup of coffee) has or appears to have a purpose (the purpose of the coffee is to quench my desire, to wake me up, to stimulate me, etc.). Anything in the chain of events to satisfy the purpose can be seen as purposive (grinding the beans, washing the cup, warming the water, etc.). For another example: I know the concept “write a letter,” thus, considering this concept, I would judge the pen and paper to be purposive.

Now … let’s remember how the 1st Moment (disinterest) forbids us to make an aesthetic judgment of the beautiful based on a concept of the thing. But, now, Kant commands that despite there being no concept (hence, no actual purpose), the aesthetical judgment presumes a purposiveness. Pay close attention to how what is absent is an “objective” or “determinate” purpose--these would be purposes that are and that determine, hence, what we lack is a purpose that would account for the beauty in the thing judged.

Beauty in nature appears to the cognitive faculties to have purposivity, but its beauty has no purpose.

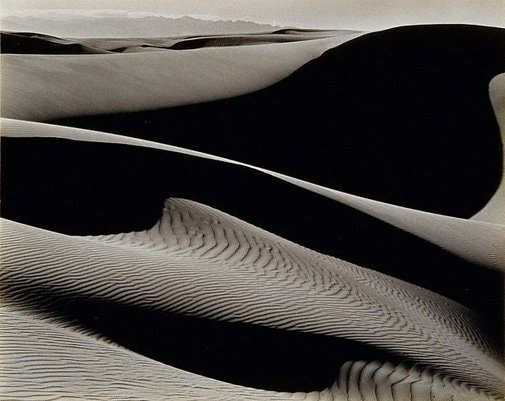

|

Kant’s claim seems to be a gross generalization … surely, it is true that some examples may prove otherwise, e.g., some flowers have evolved a certain color to attract pollinators, etc., but it is not wholly wrong: think about the lines wind forms in sand dunes (as seen here in a photograph entitled “Oceano,” by Edward Weston (1936)) ... so far as our science can tell, there is no purpose for this (even if there is a scientific explanation, it is not important—the key is that it seems like there is one, but we do not know it).

|

While simplifying the topic, it is perhaps easier to understand this claim to say that beauty in nature has no human-determined or human-related purpose (a tree in the jungle was not made for a reason; a laptop in an office was made for typing—both can give us a sense of purposiveness, but only the laptop immediately gives us its purpose). What is critical is that the representation seems to have a purpose, and therefore we can judge it, but the thing represented really does not have one (for then we could be wrong about it if our judgment did not match the existence of the thing out there). The aesthetical judgment of beauty relies upon the seeming to have of purposiveness, but the judgment is not based upon the concept of actual purpose. So, the flower is not beautiful because it attracts pollinators (this feature, no matter how true does not account for the beauty of the flower); the sand dune is not beautiful because its lines have any purpose or not. We need purposiveness to judge, but do not base the judgment upon purpose!

To discern purposiveness without purpose in the beauty in art is far more challenging because it may seem that a human artist always has reasons, and these cannot be detected (we presume) as easily as a scientific test may tell us if X has a purpose). And, it is true that there may be reasons why something was created behind the actual object represented (the artist may have plenty of concepts of form, of harmony; s/he may have external intentions of fame, fortune, memorialization, protest, etc.), but these reasons are not sufficient for an object to be judged to be beautiful (and, all these purposes behind the creation must be abstracted from consideration, re: disinterest). The work of art must seem to have purpose (its purposivity), but the judgment must not be based upon the purpose; any features of purpose do not account for the judgment of beauty, and I must look past them in making an aesthetical judgment.

Free beauty, for Kant, is beauty that is wholly free of any and all concepts. Dependent beauty, for Kant, is a judgment of beauty that is slightly entangled with concepts, and is capable only in two cases: that of perfection (an exact realization of the artist’s internal conception—but, still, this concept is not why the thing is judged as beautiful), and that of the ideal of beauty (an absolute maximum of beauty in a type (class) of things).

To discern purposiveness without purpose in the beauty in art is far more challenging because it may seem that a human artist always has reasons, and these cannot be detected (we presume) as easily as a scientific test may tell us if X has a purpose). And, it is true that there may be reasons why something was created behind the actual object represented (the artist may have plenty of concepts of form, of harmony; s/he may have external intentions of fame, fortune, memorialization, protest, etc.), but these reasons are not sufficient for an object to be judged to be beautiful (and, all these purposes behind the creation must be abstracted from consideration, re: disinterest). The work of art must seem to have purpose (its purposivity), but the judgment must not be based upon the purpose; any features of purpose do not account for the judgment of beauty, and I must look past them in making an aesthetical judgment.

Free beauty, for Kant, is beauty that is wholly free of any and all concepts. Dependent beauty, for Kant, is a judgment of beauty that is slightly entangled with concepts, and is capable only in two cases: that of perfection (an exact realization of the artist’s internal conception—but, still, this concept is not why the thing is judged as beautiful), and that of the ideal of beauty (an absolute maximum of beauty in a type (class) of things).

Necessity and Common Sense

Aesthetic judgment requires there to be, and shows us that there is, a necessary presupposition of a “common sense” amongst all who correctly judge the beautiful (this moment one sums up all 4 moments):

Common sense: a sense shared by all in common (sense: a mode of becoming aware; common: shared by all). The sense we share is the feeling for certain states of our own mind (aesthetic pleasure). This is to become, for Kant, an a priori condition of aesthetic judgment; but, he calls this a priori condition a “principle of taste” (sec. 20). A principle implies that it is a rule by which aesthetic judgment legislates for feeling.

Thus, it seems that “common sense” is three distinct things:

How do these relate together (§22)? By necessity. Necessity of judgment: if all the circumstances are present, then judgment necessarily follows. This implies universality. But, (given universality implied) the necessity is not the judgment itself, but the conditions of judgment, which is to say, according to the universal conditions of experience, i.e., the cognitive faculties involved. This is why this moment is related to the “Category of Modality”—it is “modal” in the sense of being the mode in or manner by which I judge, and not the conditions or content of the judgment itself.

How can we have necessity in judgments of taste if they have no concept? Because the necessity is singular and exemplary. Singular necessity: judgment does not rest on concepts, nor does it produce concepts; instead, it acts as if there were an universal rule incapable of expression that it follows. Exemplary necessity: a conditioned necessity (§§18-9), something else must be the case prior to and in order for the judgment to be properly formed. [An unconditioned necessity would be judgment in accord with logic or universal conditions of experience, thus, these are not really conditions at all.]

Thus, beauty is necessary BUT rests on conditions of a subjective a priori principle of feeling of taste (i.e., common sense). Thus, we see the different meanings of common sense united in the harmony or free play of the imagination (wherein cognitive faculties are applicable).

Aesthetic judgment requires there to be, and shows us that there is, a necessary presupposition of a “common sense” amongst all who correctly judge the beautiful (this moment one sums up all 4 moments):

Common sense: a sense shared by all in common (sense: a mode of becoming aware; common: shared by all). The sense we share is the feeling for certain states of our own mind (aesthetic pleasure). This is to become, for Kant, an a priori condition of aesthetic judgment; but, he calls this a priori condition a “principle of taste” (sec. 20). A principle implies that it is a rule by which aesthetic judgment legislates for feeling.

Thus, it seems that “common sense” is three distinct things:

- An a priori faculty of a feeling of beauty,

- A common aspect of feeling, and

- Subjective principle for judgment.

How do these relate together (§22)? By necessity. Necessity of judgment: if all the circumstances are present, then judgment necessarily follows. This implies universality. But, (given universality implied) the necessity is not the judgment itself, but the conditions of judgment, which is to say, according to the universal conditions of experience, i.e., the cognitive faculties involved. This is why this moment is related to the “Category of Modality”—it is “modal” in the sense of being the mode in or manner by which I judge, and not the conditions or content of the judgment itself.

How can we have necessity in judgments of taste if they have no concept? Because the necessity is singular and exemplary. Singular necessity: judgment does not rest on concepts, nor does it produce concepts; instead, it acts as if there were an universal rule incapable of expression that it follows. Exemplary necessity: a conditioned necessity (§§18-9), something else must be the case prior to and in order for the judgment to be properly formed. [An unconditioned necessity would be judgment in accord with logic or universal conditions of experience, thus, these are not really conditions at all.]

Thus, beauty is necessary BUT rests on conditions of a subjective a priori principle of feeling of taste (i.e., common sense). Thus, we see the different meanings of common sense united in the harmony or free play of the imagination (wherein cognitive faculties are applicable).

Critiques of Kant’s Aesthetics

It is beneficial to pause here to consider (outside of our reading) some of the predominate or standard critiques against Kant’s aesthetic theory because they typically focus on these four moments of the judgment of taste of the Beautiful (and may, thereby, aid our understanding of each moment)

The standard critiques include:

It is beneficial to pause here to consider (outside of our reading) some of the predominate or standard critiques against Kant’s aesthetic theory because they typically focus on these four moments of the judgment of taste of the Beautiful (and may, thereby, aid our understanding of each moment)

The standard critiques include:

- Disinterest: Duchamp’s critique (cf., under the explanation of “The Good,” above) concerned an attack on disinterest: he believed that the spectator must bring something to the art; or, another critique can be seen in Valéry’s claim that art is that which initiates an affectation within the viewer, and thus this affectation is interest and absolutely required, which is similar to Tolstoy’s theory, that art is the successful communication of the sincere feeling felt by the artist to the audience.

- Subjective: Critics will say that the beautiful can be objectively determined, that is, there is some mathematical law (maybe “proportion”) or a specific brain activity that can be measured that absolutely, quantifiably determines beauty; or, other critics may say that that Kant’s conception of subjectivity is not free enough, that beauty is far, far more relative (“beauty in the eye of the beholder, each and every last one!).

- Necessary: Critics will say that meeting these conditions (the four moments) does not then necessarily necessitate the judgment of the beautiful, either because there is more required in the judgment of the beautiful or because there is nothing herein that has a force of a cause so as to effect the cause of the judgment.

- Universally Communicable: Critics will say that matters of taste are so personal as to be private, thus, not at all universally communicable, especially across time and culture; or, others may argue that the universality can only be presumed, but cannot be communicated because that which founds the judgment is not the actual content of the work but the feeling within oneself, and there is no way to verify that the other is feeling the same as what the “I” is feeling.

- Purposiveness without a Purpose: Critics can argue that art can have a purpose, e.g., propaganda can be art and have a goal; or, other may say that the assumption of purposivity is an imposition of a concept or of interest in the judgment, and therefore violates Kant’s own theory.

What to take away from the “Analytic of the Beautiful:”

(1) the aesthetic judgment of “beauty” is different from the other two aesthetic judgments, the “good” and the “pleasant.” The beautiful is judged disinterestedly and yields mere pleasure; the good is judged as useful and yields pleasure as esteem; the pleasant is judged to satisfy our wants and yields pleasure as gratification.

(2) and that the judgment of beauty must be disinterested, universal, have purposiveness without having purpose, and be necessary. Disinterest means we approach with a suspension of our interest, our biases or wants or thoughts; universality means that, while subjective, the judgment is presumed to be universal to all who correctly judge; purposivity without purpose means that we judge as if there was purpose, but that the work itself actually has no purpose (i.e., it is not an existence thing caused for some reason); and, finally, necessity shows that when confronted by a work of art, judgment is necessary (it just does and must naturally happen), this moment sums up all the others and importantly shows that there is a “common sense” amongst all concerning aesthetic judgments.

(1) the aesthetic judgment of “beauty” is different from the other two aesthetic judgments, the “good” and the “pleasant.” The beautiful is judged disinterestedly and yields mere pleasure; the good is judged as useful and yields pleasure as esteem; the pleasant is judged to satisfy our wants and yields pleasure as gratification.

(2) and that the judgment of beauty must be disinterested, universal, have purposiveness without having purpose, and be necessary. Disinterest means we approach with a suspension of our interest, our biases or wants or thoughts; universality means that, while subjective, the judgment is presumed to be universal to all who correctly judge; purposivity without purpose means that we judge as if there was purpose, but that the work itself actually has no purpose (i.e., it is not an existence thing caused for some reason); and, finally, necessity shows that when confronted by a work of art, judgment is necessary (it just does and must naturally happen), this moment sums up all the others and importantly shows that there is a “common sense” amongst all concerning aesthetic judgments.

Reading & Discussion Prompts to Consider:

(1) Find different examples of art (any medium) that represent the beautiful, the good, and the pleasant (upload files or provide internet links) and offer your own interpretation as to why these examples fit Kant’s distinctions. Do you agree with his distinctions? Would you change them in any way?

(2) There are two main critiques leveled against Kant’s “Third Moment,” that the beautiful must have purposiveness without having an actual purpose: the first is that critics can argue that art can have a purpose, e.g., propaganda can be art and have a goal; the second is that other critics may say that the assumption of purposivity is an imposition of a concept or of interest in the judgment, and therefore violates Kant’s own theory. Thoughtfully address these two critiques: do you think they are right or wrong?, do you agree with them?, do they destroy Kant’s theory?, is there a clarification that could ease the problem?, etc.

(3) Kant’s “Fourth Moment,” that aesthetic judgment is necessary, includes a significant address of how there is a “common sense” (broached in the “Second Moment,” on universality) amongst all people concerning aesthetic judgments. Contribute some examples of art (any medium, upload or include links to them) that you believe demonstrate or disprove this common sense, and explain why.

(1) Find different examples of art (any medium) that represent the beautiful, the good, and the pleasant (upload files or provide internet links) and offer your own interpretation as to why these examples fit Kant’s distinctions. Do you agree with his distinctions? Would you change them in any way?

(2) There are two main critiques leveled against Kant’s “Third Moment,” that the beautiful must have purposiveness without having an actual purpose: the first is that critics can argue that art can have a purpose, e.g., propaganda can be art and have a goal; the second is that other critics may say that the assumption of purposivity is an imposition of a concept or of interest in the judgment, and therefore violates Kant’s own theory. Thoughtfully address these two critiques: do you think they are right or wrong?, do you agree with them?, do they destroy Kant’s theory?, is there a clarification that could ease the problem?, etc.

(3) Kant’s “Fourth Moment,” that aesthetic judgment is necessary, includes a significant address of how there is a “common sense” (broached in the “Second Moment,” on universality) amongst all people concerning aesthetic judgments. Contribute some examples of art (any medium, upload or include links to them) that you believe demonstrate or disprove this common sense, and explain why.

Before moving to notes on Kant's Analytic of the Sublime ...

A Review on How the Critical Project led to the 3rd Critique:

Kant’s critical project hinges upon a synthesis of experience and reason as the origin of knowledge and as that which grants knowledge its limits. That is, all knowledge comes from sensibility (in which objects are given and which yields intuitions) and understanding (in which objects are thought and which yields concepts). So, knowledge comes from experience that is experienced through rational, innate, a priori structures (space and time and the table of categories). This is how understanding works. The problem that we run into is when we want to know something that we cannot experience, this Kant calls Reason, rather than Understanding, and it happens in metaphysics (on cosmological, theological, and psychological questions).

So, in Understanding, judgments are determinate (has concept to subsume particulars under).

In Reason, judgments are reflective (has no full concept).

So, how does Judgment judge without a concept? Does Reflective Judgment give itself an a priori principle?

In a way, yes—it gives itself an a priori principle via Reason of the Purposiveness of Nature (although, we may also properly say that all four moments of the beautiful, the disinterest, universality, purposivity, and necessity form this principle), which can be represented via Aesthetic or Teleological Judgments. (But, we answer the question as saying yes, in a way, because we can also answer no, not entirely, because Kant’s Introduction implies that indeterminate judgments, wherein the judger must come up with a new concept by which to judge, are somewhat different than teleological and aesthetic judgments, wherein we judge according to other, related but not entirely applicable concepts in the former and that we judge without forming a new concept, but act as if we have a concept in the latter).

And, according to Lyotard, in his Lessons on the Analytic of the Sublime, trans. Elizabeth Rottenberg (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994), “The task assigned to the Critique of Judgment, as its Introduction makes explicit, is to restore unity to philosophy in the wake of the severe ‘division’ inflicted upon it by the first two Critiques” (1).

Most scholars, as Lyotard points out, and perhaps Kant himself, seeing the success of the 3rd Critique’s synthesis of the former two as residing in the latter half of the text: the teleology. This reading, as Lyotard explains it, runs thus:

A Review on How the Critical Project led to the 3rd Critique:

Kant’s critical project hinges upon a synthesis of experience and reason as the origin of knowledge and as that which grants knowledge its limits. That is, all knowledge comes from sensibility (in which objects are given and which yields intuitions) and understanding (in which objects are thought and which yields concepts). So, knowledge comes from experience that is experienced through rational, innate, a priori structures (space and time and the table of categories). This is how understanding works. The problem that we run into is when we want to know something that we cannot experience, this Kant calls Reason, rather than Understanding, and it happens in metaphysics (on cosmological, theological, and psychological questions).

So, in Understanding, judgments are determinate (has concept to subsume particulars under).

In Reason, judgments are reflective (has no full concept).

So, how does Judgment judge without a concept? Does Reflective Judgment give itself an a priori principle?

In a way, yes—it gives itself an a priori principle via Reason of the Purposiveness of Nature (although, we may also properly say that all four moments of the beautiful, the disinterest, universality, purposivity, and necessity form this principle), which can be represented via Aesthetic or Teleological Judgments. (But, we answer the question as saying yes, in a way, because we can also answer no, not entirely, because Kant’s Introduction implies that indeterminate judgments, wherein the judger must come up with a new concept by which to judge, are somewhat different than teleological and aesthetic judgments, wherein we judge according to other, related but not entirely applicable concepts in the former and that we judge without forming a new concept, but act as if we have a concept in the latter).

- Aesthetic Judgments: concern the accordance of Form (related by imagination) to the Faculties of Desire wherein Form is considered a ground of pleasure from the representation.

- Teleological Judgments: Accordance of Form with the possibility of the thing-itself; the Thing is represented by form to be fulfilling an End/Purpose of nature. The a priori regulative concept of Purposiveness connects nature (1st Critique) with freedom (2nd Critique).

And, according to Lyotard, in his Lessons on the Analytic of the Sublime, trans. Elizabeth Rottenberg (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994), “The task assigned to the Critique of Judgment, as its Introduction makes explicit, is to restore unity to philosophy in the wake of the severe ‘division’ inflicted upon it by the first two Critiques” (1).

Most scholars, as Lyotard points out, and perhaps Kant himself, seeing the success of the 3rd Critique’s synthesis of the former two as residing in the latter half of the text: the teleology. This reading, as Lyotard explains it, runs thus:

... taste at least, if not the feeling of the sublime, offers the paradox of a judgment that appears, problematically, to be doomed to particularity and contingency. However, the analytic of taste restores to judgment a universality, a finality, and a necessity—all of which are, indeed, subjective—merely by evincing its status as reflective judgment. This status is then applied to teleological judgment in order, precisely, to legitimate its use. In this way, the validation of subjective pleasure serves to introduce a validation of natural teleology

--Lyotard, Lessons on the Analytic of the Sublime, 1.

This argument seems wholly valid because of Kant’s determination that the judgment is simply reflective—that is, “The ‘weakness’ of reflection this also constitutes its ‘strength’” (ibid., 2) because reflection is a process of reunification wherein it finds the universal from the given particulars; it has no principle per se (which could legislate) by which to judge, but it is allowed a principle peculiar to itself by which laws are sought. Its weakness is manifest in its principle being “merely subjective a priori” (Kant, 15; 12); it does not determine objects, that is a task for understanding for matters of the world and for reason for matters of freedom. Instead, it judges objects as given, in their particularity; it judges them as if the rules that determined their possibility a priori were insufficient to account for their particularity thereby permitting its activity to be a seeking further for their universality from their existence, not possibility (Lyotard, 2). This principle by which it judges is transcendental; it is subjective; it is from itself and given to itself. This principle can only be applied with art. The results we take from this investigation can then be analogically applied to teleology, but Kant could not have skipped the opening half on the aesthetic, for from teleology alone, he cannot get anywhere.

As Kant ends his Introduction, “A critique [of the judging subject] … is the propaedeutic of all philosophy.”

Were this implication not strong enough, that the critique of judgment is preparatory for all philosophy, and teleology can only follow aesthetics, Lyotard underlines his reading:

“I would argue that an importance of an entirely different order may be accorded the ‘Analytic of Aesthetic Judgment,’ that of being a propaedeutic that is itself, perhaps, all of philosophy (for ‘we can at most only learn how to philosophize …,’ but we cannot learn philosophy (krv, 657, t.m.’ 752) . ... Aesthetic judgment conceals, I would suggest, a secret more important than that of doctrine, the secret of the ‘manner’ (rather than the method) in which critical thought proceeds in general”

--Lyotard, Lessons on the Analytic of the Sublime, 6.

What is this “manner?”—The manner, the “modus aestheticus,” is the feeling of unity in the presentation. What is this “method?”—the method, “modus logicus,” follows definite principles. Fine art has only manner; it has no method. Stripped of function, reflection (in these aesthetic judgments) has no claim to knowledge, it seeks only its own pleasure, it has nothing other than itself to pursue, thus, it perpetuates itself: the contemplation of the beautiful reproduces itself, strengthens itself, reproduces itself. It is a lingering that makes the mind passive, but it has its own activity herein in the self-perpetuation. It must linger; it is feeling that orients it. It is subjective, and yet it is autonomous.

V) Textual Analysis:

On The Analytic of the Sublime, §§23-29

(cf., Ross 113-27)

Analytic of the Sublime Summary: The free play of the imagination, in the estimation of the Beautiful, offers us a taste of ambrosia, it pleases. In the Sublime, the imagination, that which receives the presentation, offers us awe. Awe can be magnificent and pleasing, or it can be capable of producing in us something like fear. While the Beautiful deals with the form, with limits, the Sublime deals with the formless, the limitless. The Beautiful prompts us to admire quality, the Sublime, quantity. The Sublime plunges us into a state where our metal capacities are compromised. We are struck by formless, limitless magnitude. There is tremendous pleasure here, but it only indirectly arises from this blinded amazement into which we are rendered. We cannot remain scared of this feeling that arises in us, we must regain our reason, and then we see the Sublime as wondrous. There is repulsion and attraction; its satisfaction is not negated, but transformed into negative pleasure. This dual movement of repulsion and attraction demonstrates the sublime does have a subjective purposiveness.

Purposiveness will become the a priori principle (akin to space and time and the categories in the 1st Critique) from Reason that permits reflective judgment judge without a concept (that is, since the aesthetic is not a cognitive judgment, lacks concepts, how could it function, by what fixed lines would it judge anything?); this purposiveness of Nature can be represented through aesthetic (and teleological) judgments. To be able to think the totality of infinity demands a faculty in the mind that is supersensible; we can think the totality by indirection shown through our failure to think it. It is aesthetic estimation of magnitude that tries to comprehend that which exceeds the capacity of the imagination to comprehend.

* * *

Note: There are more notes below on sections beyond what we will read from Ross' anthology selections of Kant ... nevertheless, they may well help you best understand the Analytic of the Sublime

* * *

§23 Transition from the faculty which judges of the Beautiful to that which judges of the Sublime

Commonalities between the beautiful and sublime:

- (1) both please in themselves (yield mere, indeterminate satisfaction)

- (2) neither are a judgment of sense

- (3) neither are a logically determined judgment

- (4) both are a judgment of reflection

- (5) their satisfaction depends neither upon sensation (as in pleasant) nor concept (as in good)

- (6) neither yield knowledge, but only feeling of pleasure

- (7) both singular, yet universal judgments

- (8) both employ imagination in accord with and furthers the faculty of concepts in Understanding and Reason

Differences between the beautiful and sublime:

(1)

- Beautiful: concerned with form of the object, has boundaries

- Sublime: concerned with the formless, shows no boundaries yet invokes totality

(2)

- Beautiful: presentation of an indefinite concept of the Understanding

- Sublime: presentation of an indefinite concept of Reason

(3)

- Beautiful: satisfaction bound up with quality

- Sublime: satisfaction bound up with quantity

(4)

- Beautiful: positive pleasure—pleasure directly tied to furtherance of life; compatible with charms and play of imagination (freies Spiel)

- Sublime: negative pleasure—pleasure had indirectly through its challenge to our vital powers and our conquering this challenge; compatible with the exercise of imagination, which is antithesis to the free play of imagination

(5)

- Beautiful: natural beauty has purposiveness in its form, which makes the object seem to be pre-adapted to our judgment

- Sublime: seems to violate purpose in judgment, that is, it seems to be vehemently unsuitable for our capacity to judge and to do violence to imagination—and, from this, it is yet judged to be even more perfectly sublime (he seems to say no purposiveness, but in §26, he affirms it does have such)

(6)

- Beautiful: has purposiveness (in nature and art) that extends our concept of nature (not our cognition of natural objects)

- Sublime: lacks this extending aspect that leads one to objective principles and their corresponding forms in nature… instead, more so, nature excites ideas of sublime the most in its greatest chaos (p.63) (Again, he seems to say sublime has no purposiveness, but in §26, he affirms it does have such)

(7)

- Beautiful: its study is more important because its purposiveness leads us to seek an external ground (after the internal presentation of the representation to Reason through imagination) (it is form that is the ground of pleasure in presentations)

- Sublime: its study is a “mere appendix to the aesthetical judging” because it does not lead to any presentation of form in nature beyond itself, it leads us only back to an inner ground within ourselves to find its cause (p.63)

* * * * * * * * * * *

. . . Before Proceeding . . . a few further notes on points of difference numbers 4 & 5 . . .

(more on difference #4 ~~ concerning the differing types of pleasure and that to which each is tied ~~)