Leo Tolstoy’s “What is Art?,”

Cf. Ross' A&S, pp.178-81

On Leo Tolstoy:

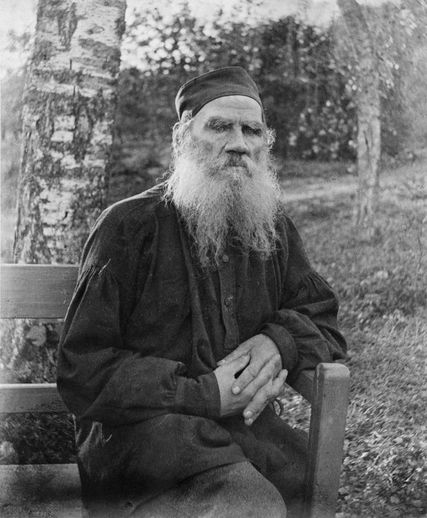

Leo Tolstoy, in 1897

Leo Tolstoy, in 1897

The Russian Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy (1828-1910) is primarily known as a writer of novels, stories, plays, and essays, although forged important theoretical paths in ethics (theoretically anarchist, socially pacifist), aesthetics, educational reform, and religious interpretation. He was born into a notable, noble family, but his parents died when he was young, and he was raised by relatives (along with his four siblings). Initially a bad student (although later learning over a dozen languages and becoming a famous writer), he left University early and spent time living the heavy gambling life before joining the army in 1851 (first in Caucasus and then fighting in the Crimean War), about the time he began writing. In 1855 he left the army and in the late 1850’s, he became committed to an ascetic, non-violent political program. He is considered one the greatest Russian writers, with his most notable works being War and Peace and Anna Karenina, which embody his spiritual, political, and ethical radicalism. Falling in love in the 1860’s, he married Sophia Andreevna Behrs (Sonya) in 1862 and they had 13 children. Thereafter, he committed himself to his writing, although also travelled Europe, witnessing political unrest firsthand and meeting notable influences from Victor Hugo to Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (the French anarchist). Other strong influences on his thought include Arthur Schopenhauer’s aesthetics and ascetic ethics, Mahatmas Gandhi’s Satyagraha (non-violent civil disobedience), and Henry George’s economic theory. He suffered an existential crisis in the late 1870’s, becoming depressed and suicidal; after this, his political radicalism heightened and his writings further embodied intense political and religious critiques. He was excommunicated from the Russian Orthodox Church, although his later years witnessed an intense, albeit radical, embrace of the teachings of Jesus (his The Kingdom of God is Within You, of 1893, reread the Bible as centered upon the idea of loving one’s neighbor and turning the other cheek).

On Tolstoy’s Aesthetic Theory:

Summary and Analysis:

Two points to note, reflect upon, from the anthology's introduction:

Tolstoy’s “What is Art?” is a clear, concise expression of how art must be an expression of an artist’s emotion that is clearly communicated to recipients who then become “infected” by the affect so as to thereby experience for their selves that same emotion.*

“The activity of art is based on the fact that a man

receiving through his sense of hearing or sight

another man’s expression of feeling,

is capable of experiencing the emotion which moved the man who expressed it” (178).

Tolstoy offers numerous examples of the transmission, for example, a person laughing makes those around him/her feel merry themselves. The capacity we have for receiving this transferred emotion, perhaps something like empathy, is the ground upon which the activity of art is based.

Tolstoy continues by explaining how art begins and its aim. The object or aim of art is in “joining another or others to himself in one and the same feeling …” (178). It begins, then, by the artist’s external expression of his/her emotion. This expression, as Tolstoy offers through an example of a boy’s encounter with a wolf, can be done by relating the encounter: he “describes himself, his condition before the encounter, the surroundings, the wood, his own light-headedness, and then the wolf’s appearance, its movements, the distance between himself and the wolf, and so forth” (179). This recounting of the experience, the narrative chronicle, engages the artist in a re-experience of the event—s/he goes through it (affectively) again in its telling (this re-experience is as important as the experience aroused in another for the judgment of X to be art). Of course, while this example may be the written or told art form, the method can be mimicked in two-dimensional art, three-dimensional art, film, music, dance, etc.

There is an important question here, however, as to how much the narrative is required. It is clear that Tolstoy’s theory is based in the idea that art is communication, that it is communicative. But, is there a tension between communication as a narrative transmission and Tolstoy’s greater emphasis that the communication is the creation of a contagion of affective experience. After being exposed to the art, are we to know something, or simply feel something. His theory suggests the latter, but his description of the method suggests the former.* Tolstoy does, twice, issue that the decision whether something is art and its quality is made “apart from its subject-matter” (180, 181)--thus, it seems that rational sense is less at stake than the conveyance of affective sense.

An additional important note about the ‘how’ of art is that the artist need not have experienced something in reality, but can invent an encounter, so long as the invention transmits real emotion. “Even if the boy had not seen a wolf but had frequently been afraid of one, and if, wishing to evoke in others the fear that he had felt, he invented an encounter with a wolf and recounted it so as to make his hearers share the feelings he experience when he feared the wolf, that also would be art” (179). This is important to connect to his later requirement about the sincerity of the artist (cf., p.180). It is worthy of consideration as to whether we can expand and/or loosen this theory up a little bit to propose whether the artist may not just have a fear of a specific thing, and then invents the story about that thing, but, rather, if s/he may invent a story inspiration of the emotion in general. For example, the boy need not have “frequently been afraid” of a wolf, but had experienced deep fear, perhaps of the dark, of a violent fight, of spiders, of the unknown, or whatever else completely unconnected to wolves, and yet invents the story of the wolf so as to arouse a similar fear in others. That is, how literal and direct must the object of the work be? Tolstoy’s later comment about judging “the quality of every work of art considered apart from its subject matter” suggests that this may be a legitimate expansion (180), although his requirement about art being “individual” may work against this expansion (180).

Moving now to consider the feelings being communicated, Tolstoy explains that they are many and diverse (patriotism, devotion, religious, love, courage, merriment, etc.), and can be “very strong or very weak, very important or very significant, very bad or very good …” (179). There are many questions that must be explored concerning these feelings, cf. below for more on this point.

Tolstoy sums up his theory in the two italicized paragraphs on p.179:

To evoke in oneself a feeling one has once experience and, having evoked it in oneself then by means of movements, lines, colours, sounds, or forms expressed in words, so to transmit that feeling that others experience the same feeling—this is the activity of art.

Art is a human activity consisting in this, that one man consciously, by means of certain external signs, hands on to others feelings he has lived through, and that others are infected by these feelings and also experiences them …. (p.179).

Note, here, that art, then, is restricted to being a conscious human enterprise—the grand canyon or chirping of a bog full of frogs cannot be art; paintings done by gorillas or cats cannot be art; an assemblage of objects done accidentally by a person cannot be art.

Tolstoy then moves to a consideration of judging excellence in art. This is done by determining the “degree of infectiousness” of art (179). “The stronger the infection the better is the art …” (179). The subject matter itself is not to be considered—so, if it is a painting of a teacup full of kittens or a battlefield, a composition performed with kazoos or violins, such things are irrelevant.

There are three conditions for this degree of infectiousness, although Tolstoy also argues that they can be reduced to the most important, third condition:

Tolstoy (the good Russian) considers “peasant art” to always be the most sincere form of art, and acts most strongly upon us; in contrast, “upper-class art,” which is the prevailing norm, is the least sincere and has the weakest affective power over us.

All three of these conditions must be met for something to be art. The degree of these conditions is that by which we judge the excellence of the work.

... See below the images for a list of questions to consider on Tolstoy's aesthetic theory ...

Two points to note, reflect upon, from the anthology's introduction:

- “… Russian impulse toward unification and communication” (177)

- “… art succeeds when it arouses and transmits emotion, when it brings people together and enriches their common humanity” (177)

Tolstoy’s “What is Art?” is a clear, concise expression of how art must be an expression of an artist’s emotion that is clearly communicated to recipients who then become “infected” by the affect so as to thereby experience for their selves that same emotion.*

- *: For the medical illusion of infection, etc., cf., Jacob Emery, “Art is Inoculation: The Infectious Imagination of Leo Tolstoy,” The Russian Review 70 (2011): 627-45.

“The activity of art is based on the fact that a man

receiving through his sense of hearing or sight

another man’s expression of feeling,

is capable of experiencing the emotion which moved the man who expressed it” (178).

Tolstoy offers numerous examples of the transmission, for example, a person laughing makes those around him/her feel merry themselves. The capacity we have for receiving this transferred emotion, perhaps something like empathy, is the ground upon which the activity of art is based.

Tolstoy continues by explaining how art begins and its aim. The object or aim of art is in “joining another or others to himself in one and the same feeling …” (178). It begins, then, by the artist’s external expression of his/her emotion. This expression, as Tolstoy offers through an example of a boy’s encounter with a wolf, can be done by relating the encounter: he “describes himself, his condition before the encounter, the surroundings, the wood, his own light-headedness, and then the wolf’s appearance, its movements, the distance between himself and the wolf, and so forth” (179). This recounting of the experience, the narrative chronicle, engages the artist in a re-experience of the event—s/he goes through it (affectively) again in its telling (this re-experience is as important as the experience aroused in another for the judgment of X to be art). Of course, while this example may be the written or told art form, the method can be mimicked in two-dimensional art, three-dimensional art, film, music, dance, etc.

There is an important question here, however, as to how much the narrative is required. It is clear that Tolstoy’s theory is based in the idea that art is communication, that it is communicative. But, is there a tension between communication as a narrative transmission and Tolstoy’s greater emphasis that the communication is the creation of a contagion of affective experience. After being exposed to the art, are we to know something, or simply feel something. His theory suggests the latter, but his description of the method suggests the former.* Tolstoy does, twice, issue that the decision whether something is art and its quality is made “apart from its subject-matter” (180, 181)--thus, it seems that rational sense is less at stake than the conveyance of affective sense.

- *: On this question of transmission, cf., S. K. Wertz, “Human Nature and Art: From Descartes and Hume to Tolstoy,” Journal of Aesthetic Education 32, n.3 (1998): 75-81.

An additional important note about the ‘how’ of art is that the artist need not have experienced something in reality, but can invent an encounter, so long as the invention transmits real emotion. “Even if the boy had not seen a wolf but had frequently been afraid of one, and if, wishing to evoke in others the fear that he had felt, he invented an encounter with a wolf and recounted it so as to make his hearers share the feelings he experience when he feared the wolf, that also would be art” (179). This is important to connect to his later requirement about the sincerity of the artist (cf., p.180). It is worthy of consideration as to whether we can expand and/or loosen this theory up a little bit to propose whether the artist may not just have a fear of a specific thing, and then invents the story about that thing, but, rather, if s/he may invent a story inspiration of the emotion in general. For example, the boy need not have “frequently been afraid” of a wolf, but had experienced deep fear, perhaps of the dark, of a violent fight, of spiders, of the unknown, or whatever else completely unconnected to wolves, and yet invents the story of the wolf so as to arouse a similar fear in others. That is, how literal and direct must the object of the work be? Tolstoy’s later comment about judging “the quality of every work of art considered apart from its subject matter” suggests that this may be a legitimate expansion (180), although his requirement about art being “individual” may work against this expansion (180).

Moving now to consider the feelings being communicated, Tolstoy explains that they are many and diverse (patriotism, devotion, religious, love, courage, merriment, etc.), and can be “very strong or very weak, very important or very significant, very bad or very good …” (179). There are many questions that must be explored concerning these feelings, cf. below for more on this point.

Tolstoy sums up his theory in the two italicized paragraphs on p.179:

To evoke in oneself a feeling one has once experience and, having evoked it in oneself then by means of movements, lines, colours, sounds, or forms expressed in words, so to transmit that feeling that others experience the same feeling—this is the activity of art.

Art is a human activity consisting in this, that one man consciously, by means of certain external signs, hands on to others feelings he has lived through, and that others are infected by these feelings and also experiences them …. (p.179).

Note, here, that art, then, is restricted to being a conscious human enterprise—the grand canyon or chirping of a bog full of frogs cannot be art; paintings done by gorillas or cats cannot be art; an assemblage of objects done accidentally by a person cannot be art.

Tolstoy then moves to a consideration of judging excellence in art. This is done by determining the “degree of infectiousness” of art (179). “The stronger the infection the better is the art …” (179). The subject matter itself is not to be considered—so, if it is a painting of a teacup full of kittens or a battlefield, a composition performed with kazoos or violins, such things are irrelevant.

There are three conditions for this degree of infectiousness, although Tolstoy also argues that they can be reduced to the most important, third condition:

- (1) The greater or lesser individuality of the feeling

- “Individual” is an interesting and ambiguous designation—does this mean “personal” or “unique?” For example, would a greatly individual feeling be femininity expressed by a woman artist, disassociation expressed by a schizophrenic, piety expressed by a priest? Or, would it be more like the feeling of fear of being lost in the alps when one is twelve on a cloudy day? Or, more like a peculiar melancholy that is also anxious and happy?

- explaining the third condition, Tolstoy links it to the first: “if the artist is sincere he will express the feeling as he experienced it. And as each man is different from everyone else, his feeling will be individual for everyone else; and the more individual it is--the more the artist has drawn it from the depths of his nature ...” (180)--hence, it seems that that individual may be read as individualized, or personalized, for each, yet most capable for universal, individual experience.

- “Individual” is an interesting and ambiguous designation—does this mean “personal” or “unique?” For example, would a greatly individual feeling be femininity expressed by a woman artist, disassociation expressed by a schizophrenic, piety expressed by a priest? Or, would it be more like the feeling of fear of being lost in the alps when one is twelve on a cloudy day? Or, more like a peculiar melancholy that is also anxious and happy?

- (2) The greater or lesser the clarity of the feeling

- Presumably, the clarity is that the feeling being transmitted itself is very clear (anger is anger—something unambiguous). It is worth while to pay close attention to exactly how Tolstoy describes this condition: “The clearness of expression assists infection because the recipient who mingles in consciousness with the author is the better satisfied the more clearly the feeling is transmitted which as it seems to him he has long known and felt and for which he has only now found expression” (180).

- Note in this quote all the supplemental issues that are raised:

- --The audience “mingles in consciousness with the author”—we can imagine some shared space of affective consciousness into which art brings us; “mingling” suggesting something more dynamic and cooperative than a mimetic theory wherein the audience’s experience mimics the artist’s experience.

- (Yet, does this conflict with the first characteristic of something highly individualized? If it is to be radically subjectively felt, is it first personal and then, while also felt universally, it renders a mingling?)

- --The audience’s reception of the emotion causes the feeling of satisfaction—so, the audience feels both emotion X and satisfaction.

- --The audience experiences (as well?) a feeling of revelation—as if s/he had long known the emotion X, but now it is finally concretized in expression. Here, it is not pure novelty (which ties to the first condition), but a ‘new old’ realization.

- --The audience “mingles in consciousness with the author”—we can imagine some shared space of affective consciousness into which art brings us; “mingling” suggesting something more dynamic and cooperative than a mimetic theory wherein the audience’s experience mimics the artist’s experience.

- (3) The greater or lesser the force of the feeling in the artist (his/her “sincerity”)

- This condition Tolstoy sites as the most important, and can encompass the other two. The sincerity rests in the intentions of the artist.* When the audience feels it is for her/himself, the sincere force is great, and thus the work is a better form of art; when the audience feels it is created for others, the sincere force of the art is lessened dramatically. In this latter case, the art can cease to even be art, and can be repulsive, rather than attractive.

- * Sincerity in the artist invokes the question of intention: does s/he create for her/himself, or for others? Tolstoy notes the boy with wolf tale tells the tale “in order to evoke” the feeling and is “wishing to evoke in others” (179), hence, the objective must be to “infect” others ... but he also says the artist's art must be made “for himself and not merely to act on others” (180) ... ?

- How do we judge the sincerity of the artist? Perhaps the artist knows his or her own sincerity, but this theory is for us to judge whether something is art and whether it is good or not art, so how are we to know whether the artist was genuine or just especially talented at seeming genuine?

- This condition Tolstoy sites as the most important, and can encompass the other two. The sincerity rests in the intentions of the artist.* When the audience feels it is for her/himself, the sincere force is great, and thus the work is a better form of art; when the audience feels it is created for others, the sincere force of the art is lessened dramatically. In this latter case, the art can cease to even be art, and can be repulsive, rather than attractive.

Tolstoy (the good Russian) considers “peasant art” to always be the most sincere form of art, and acts most strongly upon us; in contrast, “upper-class art,” which is the prevailing norm, is the least sincere and has the weakest affective power over us.

- If we take “peasant” to translate to “the many” or “the populous,” hence “popular art”--today we may wonder if the most popular art of today is the strongest affectively over us, but in a wholly new way, a less genuine way ... is not much popular art very much crafted to appeal, and therefore deemed less authentic or sincere? Further, some may argue that we are so indoctrinated into a certain aesthetic view that it forms the basis of what we deem art, it does not arouse a true, authentic community empathy, but only invites us to be further entangled in the constructed and sold to us world view.

All three of these conditions must be met for something to be art. The degree of these conditions is that by which we judge the excellence of the work.

... See below the images for a list of questions to consider on Tolstoy's aesthetic theory ...

Reflection Questions:

- Tolstoy argues that for something to be art, it must have all three characteristics--individual, clearness, sincerity--"The absence of any one of these conditions excludes a work from the category of art and relegates it to that of art's counterfeits" (180). These characteristics can be had more or less--"in all possible degrees and combinations" (181)--but must be present. What do you think of this requirement of all three? Would you add or subtract other characteristics?

- The first required characteristic of art is that its feeling is felt as “individual”--yet the most individual feeling, since, Tolstoy admits "each man is different from everyone else," may be what most singularizes a person from other people, i.e., what makes one most minoritarian, e.g., alienation in an agoraphobic, forgotteness in the abandoned, ecstasy in the religious mystic, disassociation expressed by a schizophrenic, piety expressed by a priest, etc. ... so, does this violate the demand that for it to be art and good art, it must 'infect' the most?

- How do we judge the sincerity of the artist? Perhaps the artist knows his or her own sincerity, but this theory is for us to judge whether something is art and whether it is good or not art, so how are we to know whether the artist was genuine or just especially talented at seeming genuine?*

- * as Tolstoy does admit the boy in his example need not have actually encountered a wolf, he could invent the story so as to convey a feeling of fear ...

- Tolstoy's aesthetic theory would not consider something art if the artist created it to be expressive of his/her feeling of fear, yet it aroused in viewers the feeling of hilarity. However, do we place the blame for this work not being art solely on the artist? Are there cases where it may be the fault of the viewers for ‘not getting it?’ (e.g., consider the initial reaction audiences had to Stravinsky's "Rite of Spring" ... see here and here for some background.)

- Tolstoy's aesthetic theory evidences the idea that art is essentially expression, it communicates--while what is communicated is affective (feeling), not rational (subject matter), since the evaluation of communication as successful generally is held to be "communication is only communication if it communicates X from you to me, so if I receive Y, we did not communicate," how do we know that my feeling of X feels the same to you? How do we validate the successful receipt of a feeling?

- Because of the difficulties of validation of feeling, perhaps this is why Tolstoy argues, for the "clearness" of feeling by saying "the recipient ... mingles in consciousness with the author" ... which suggests art as communication may be better read as art as a communion, a sharing, exchanging of emotions.

- However ... "mingling" here does seem to contradict the first characteristic art must have, that of "individuality."

- Because of the difficulties of validation of feeling, perhaps this is why Tolstoy argues, for the "clearness" of feeling by saying "the recipient ... mingles in consciousness with the author" ... which suggests art as communication may be better read as art as a communion, a sharing, exchanging of emotions.

- Expressing & Arousing Emotion: Tolstoy’s communication of emotions requires an arousing of emotions; Collingwood, however, argues that communication of emotions is expression, not an arousing of emotions ... :

- While Collingwood’s ideas smooth out a lot of issues with Tolstoy’s theory, it also suggests art experience and judgment is either more intellectual (hence very opposed to Kant’s idea of it as subjective feeling) or requires a form of emotional disinterest (using Kant’s idea, but in a non-Kantian way). How do you understand the ideas of expressing emotion and arousing emotion, if they are co-implicatory or distinct, in Tolstoy and Collingwood? How do you evaluate their different accounts of the emotional dimension of art?

- For Collingwood, since art is the expression of feeling as the artist coming to understand what the feeling is, it is likely that the art work may reflect some of the initial ambiguity of what the feeling is; for Tolstoy, "if it [the feeling] is unintelligibly expressed ... it is not a work of art" (180-80) ... what do you think of the latter's possible restriction of art that the former may allow?

Some External Resources:

Sample Artworks for Consideration:

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by MacHighway