Oh, an ode, hardly, instead of a hoe-full, this is a woe-full inventory of & reflection on weeds ...

© Dr. Mélanie V. Walton, 2021

I begin with the woe of weeds. Nearly two handfuls of years ago utopia opened her arms to me as I moved house up a zone, from an USDA 6 to 7—but then she revealed herself as wily as any leprechaun or genie: your seedlings can go out a month earlier, your harvests will keep coming so much longer, your once-annuals are now returning friends, but this rich soil, these bright skies, and our long season is wholly equal-opportunity in growth for all. Remember those occasional dandelions and little tufts of weeds you’d spot here or there?, no need to look for them here, you cannot see anything but them everywhere. The compost bin you built could let a small horse have a cozy stall, but it will be the laughingstock of utility when you finish weeding. Don’t fret, though, you will never finish weeding. Think you cleared a bed?, look again, then look tomorrow, and then again: Little Shop of Horrors meets industrial scale manufacturing and is the horror flick you are stuck in now, on repeat. Watch, listen closely, you can even hear the roiling of germination, cotyledons ready to explode forth everywhere. You will never, ever finish weeding.

What’s a philosopher to do?

“Philosophy begins in wonder,” intones Socrates in Plato’s Theaetetus and Heidegger sighs, eons later, opening his Being and Time imploringly on how we just no longer let ourselves be perplexed. So, let me try to be surprised. I simply need to open a new perspective on weeds. Phenomenology, Gestalt theory, postmodernism—all embolden our eyes and minds to expanded vistas, grasp greater complexities, link them and to the beyond more creatively. Is it not, too, just like the mother encouraging her toddler to take a bite, you might just like it? Maybe if I try, if I get to know my weeds, I may gain some better appreciation for them? (And, even if it proves to be simply a matter of ‘if you can’t fight them, then join them,’ still, Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling reveals there is power inherent in resignation—such can never be a wholly passive giving in.)

Let me give it a try ...

... though, with ...

|

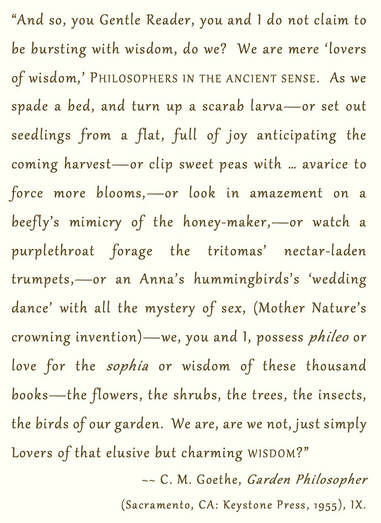

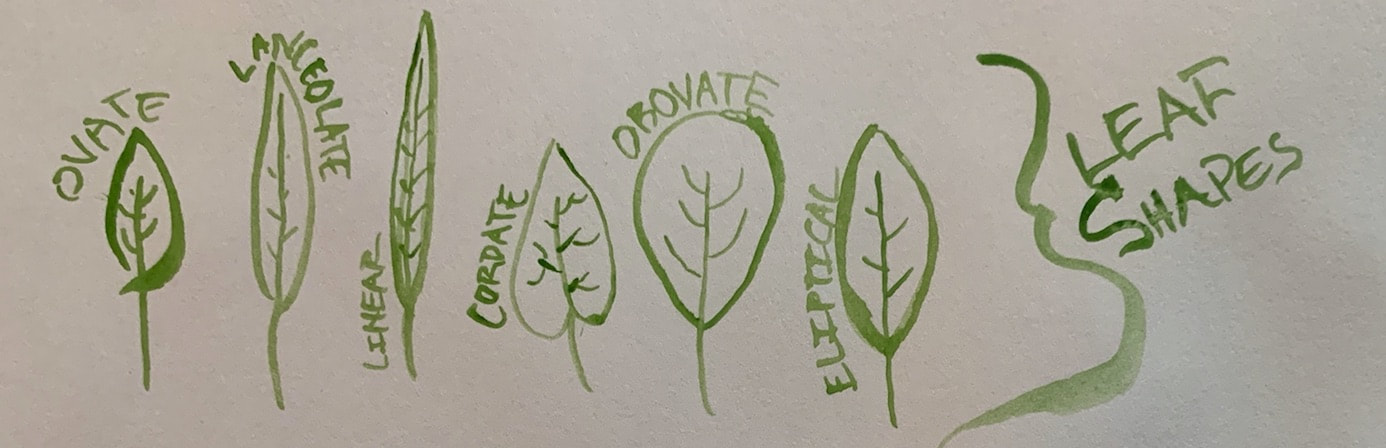

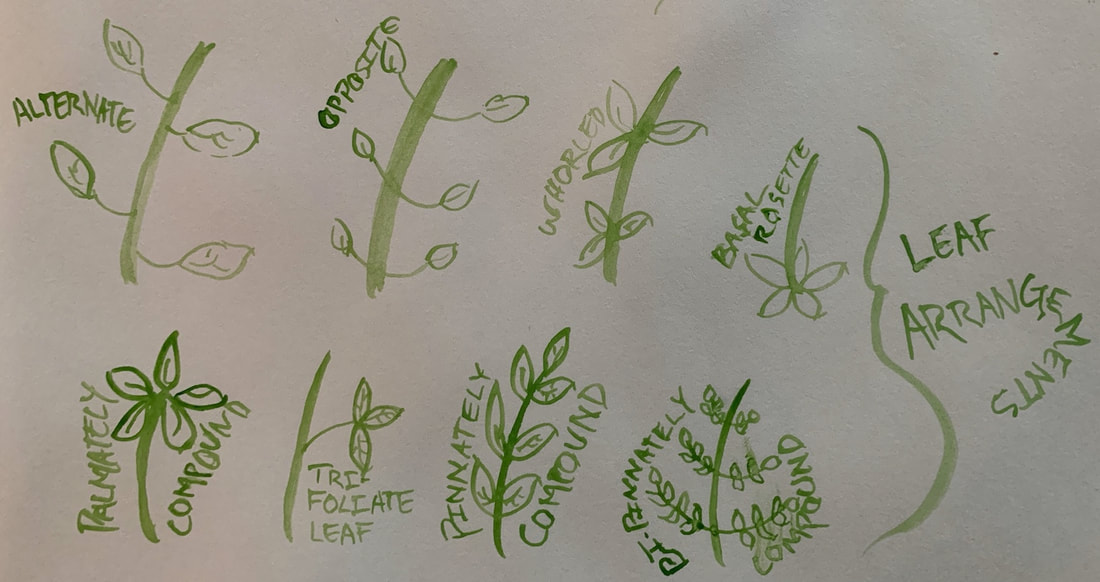

Two Prefacing Notes & Identifying Diagrams:

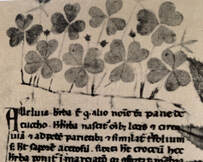

1-- I am side-stepping debate as to the nature of the weed until the end ... keeping the question in mystery akin to the etymology of “weed”: while by way of the Proto-Germanic *weud-, its origins are unknown. So, for now: despite any variability in what you or I may identify by it, I say “weed,” & you -know- what I mean ... we all know well the offenders, know them by their vehement assaults to garden beds, our lovingly toiled over soils that suffer so due those incessant, pernicious flora invaders. 2-- Do mind that many of the curative & palliative insights here come from late antique through medieval philosophical & folk or literary sources, readings undertaken for intellectual interest & philosophical insight, NOT for any medical or gustative advisement ... i.e., do NOT try these without your own further, contemporary, & most rigorous research. |

ƒ › › ¥ ¢ ˛ ¢ ¥ › › ƒ

|

Contents:

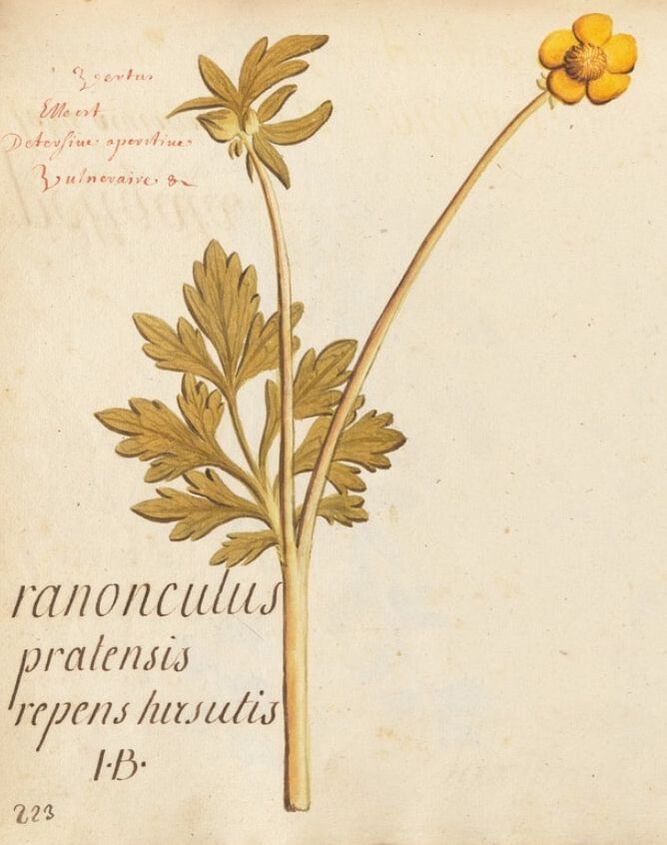

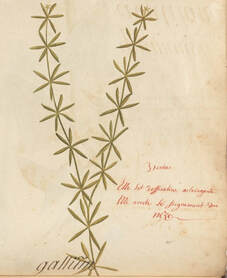

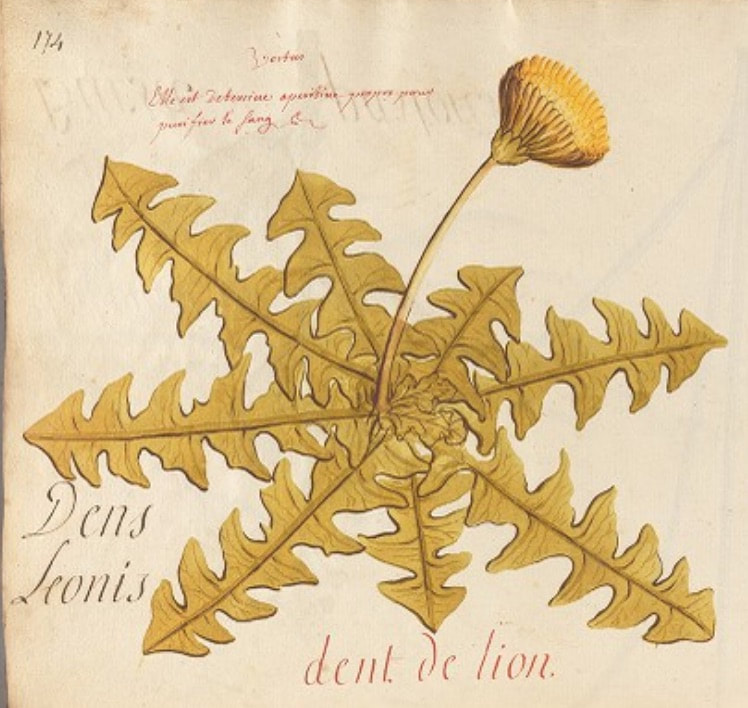

1) Plantain (Plantago major) 2) Creeping Charlie (Glechoma hederacea) 3) Smilax (Smilax rotundifolia or S. bona-nox) 4) Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana) 5) Porcelainberry (Ampelopsis brevipedunculata) 6) Bush / Amur Honeysuckle (Lonicera Maackii) 7) Privet (Ligustrum sinense) 8) Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) 9) Wintercreeper (Euonymous fortunei) 10) Ivy (Hedera helix) 11) Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana and Duchesnea indica) 12) Violets (Viola spp.) 13) Speedwell (Veronica officinalis or V. americana) 14) Dock (Rumex spp.) 15) Buttercups (Ranunculaceae) 16) Crownvetch (Securigera varia) 17) Spurge (Euphorbia humistrata or E. maculata) 18) Bedstraw / Cleavers (Galium aparine) 19) Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) 20) Virginia Threeseed Mercury (Acalypha virginica) 21) Pennsylvania Smartweed (Polygonum pensylvanicum) 22) Pigweed (Amaranthus palmeri) 23) Virginia Buttonweed (Diodia virginiana) 24) Oxalis (Oxalis stricta) 25) Creeping Cucumber (Melothria pendula) 26) Whitestar / Small White Morning Glory (Ipomoea lacunose) 27) Bindweed (Convolvus arvensis) 28) Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans or T. rydbergii) 29) Fleabane (Erigeron annuus or E. strigosus) |

The following are located on page two, link ~~HERE~~ & at bottom:

30) Pilewort (Erechtites hieraciifolius) 31) Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) 32) Swamp Rose-Mallow and Rose of Sharon (Hibiscus moscheutos and H. syriacus) 33) Mystery Umbellifer, maybe Wild Carrot (Daucus carota) or Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca), probably Field Hedge Parsley (Torilis arvensis) 34) Mystery Asteraceae, maybe a wild species of Black- or Brown-Eyed Susan (Rudbeckia) 35) Mystery Giant, maybe a Giant Ragweed (Ambrosia trifida) 36) Sweet Annie (Artemisia annua) 37) Mulberry Weed (Fatoua villosa) 38) Red Mulberry Tree (Morus rubra) 39) Hackberry Tree (Celtis occidentalis) 40) American Elm (Ulmus americana) 41) White and Southern Red Oaks (Quercus Alba and Quercus falcata) 42) Cross Vine (Bignonia capreolata) 43) Star of Bethlehem (Ornithogalum umbellatum) 44) Garlic Chives (Allium tuberosum) 45) Late-Flowering Thoroughwort (Eupatorium serotinum) 46) Figwort (Scrophularia marilandica) 47) Italian Arum (Arum italicum) 48) Cranesbill (Geranium, likely G. carolinianum or G. bicknellii) The following are located on page three, link ~~HERE~~ &at bottom: 49) Henbit & Red Dead-Nettle (Lamium amplexicaule & L. purpureum) 50) Chickweed (Stellaria media) 51) Crow Garlic (Allium vineale) 52) Little-leaf or Fig-leaf Buttercup (Ranunculus abortivus) 53) Smallflower Baby Blue Eyes (Nemophila aphylla) 54) Black Medic (Medicago lupulina) 55) Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) 56) Perilla (Perilla frutescens) 57) Oriental False Hawksbeard (Youngia japonica) |

ƒ › › ¥ ¢ ˛ ¢ ¥ › › ƒ

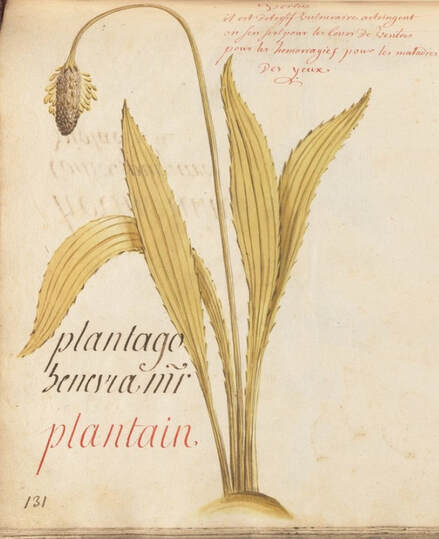

1)

Your common names are nearly as many as the lands you cover, many of these prefixing ‘plantain’ by common, ground, greater, major, dooryard, cart track, roundelay, English, broad-leaved, birdseed, ripple grass, and ripple-seed, cuckoo’s bread, snakeweed, as well as the curious white man’s foot (translating the Native American denotation of you who seemed to spread everywhere the white man went, but also akin to “plantain” and “Plantago” coming from the Latin planta, or ‘sole of the foot,’ for the shape of your flat leaves) and waybread (“The Anglo-Saxon names ‘Waybroad’ or ‘Waybread’ simply mean ‘a broad-leaved herb which grows by the wayside’†).††

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~Footnotes (as immediately following) are listed within &/or at the ends of each entry with full citation information, but a full, growing bibliography can also be found on the ‘Weed Reflections’ page, available ~~HERE~~

* Gareth Richards, Weeds: The Beauty and Uses of 50 Vagabond Plants (London: Royal Horticultural Society and Welbeck Publishing Group, 2021), 136.

** Richard Mabey, Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants (New York: Harper-Collins, 2010), 77.

*** Richard Dickinson and France Royer, Weeds of North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 538-39; North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox page, available ~~HERE~~; Minnesota Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; Plants for a Future page, available ~~HERE~~.

† Richard Mabey, Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants (New York: Harper-Collins, 2010), 77.

††Richard Dickinson and France Royer, Weeds of North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 538-39; North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox page, available ~~HERE~~; “Plantain (n.2),” Online Etymology Dictionary, available ~~HERE~~.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~Footnotes (as immediately following) are listed within &/or at the ends of each entry with full citation information, but a full, growing bibliography can also be found on the ‘Weed Reflections’ page, available ~~HERE~~

* Gareth Richards, Weeds: The Beauty and Uses of 50 Vagabond Plants (London: Royal Horticultural Society and Welbeck Publishing Group, 2021), 136.

** Richard Mabey, Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants (New York: Harper-Collins, 2010), 77.

*** Richard Dickinson and France Royer, Weeds of North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 538-39; North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox page, available ~~HERE~~; Minnesota Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; Plants for a Future page, available ~~HERE~~.

† Richard Mabey, Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants (New York: Harper-Collins, 2010), 77.

††Richard Dickinson and France Royer, Weeds of North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 538-39; North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox page, available ~~HERE~~; “Plantain (n.2),” Online Etymology Dictionary, available ~~HERE~~.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Just as many are the ailments you have reputedly aided. According to the Old English Herbarium, a widely copied herbal translated into Anglo-Saxon around 1000 c.e., common plantain (therein named arniglosa) serves 22 ailments, including: aches of the head, stomach, and abdomen, wounds and anal bleeding, worms or snakebites (the latter requiring the plant is well muddled in wine), “For a hard place on the body,” all sorts of fevers, infections, gout, sores, and nose pustules, mad dog bites, and “For daily internal weakness” (this last one, the editor supposes, may be an older instantiation of the German custom for a mid-morning schnapps that helps one to overcome “the dead time”).† † † Ruth Binney, in Plant Lore and Legend, reports that Nicholas Culpeper, the early modern writer of The English Physitian, prescribed plantain’s juice, mixed with that of houseleek, were effective to treat burns and “good for all inward heats and out.”††††

Another species of the Plantago genus, P. media, or the hoary plantain, was introduced to the north-eastern United States from central and western Europe and appears in the 1920-30’s ethnobotany notes of Huron Smith as a medical plant used by the Native American Winnebagos who would finely chop the leaves to make a poultice to heat old sores, and additionally feed a little to cure unwell horses.∆ Smith’s research on the Menomini Native Americans documents the use of the leaves of Plantago major and its paler relation, P. rugelii (also differentiated, barely, by a slight reddish tinge on its petioles), warmed and bandaged on skin, to treat swellings and infections. In a self-experiment, Smith reported on his own swollen and infected hand clearing drastically in the course of one day after profuse sweating, although went on to note more dismissively that “Plantain has been thought by the white man to possess curative powers in many diseases, although it is really a very feeble remedy.”∆∆ Smith repeats the story of his own experience and elaborates his nevertheless skeptical opinion of Plantago (“feeble,” but “ascribed potency in many diseases by eclectic practioners”) when later reporting that the Ojibwe native Americans of the Wisconsin area also use plantain leaves, soaked in warm water and then bound on bruises, sprains, or sores, widely soothing burns, scalds, bee stings, and snake bites, as well as using its ground root to ward off snakes.∆ ∆ ∆ Plantain’s benefit for bleeding and burns is twice further affirmed in the 1970’s, first in the American Encyclopedia of Medicinal Herbs, and then in the British Encyclopedia of Herbs and Herbalism.◊

The use of plantain against snakes has a long, but less convincing, history. The Old English Herbarium instructs one who is suffering snake bites, quartan fever (malaria), or poor hearing, to seek what it first identifies as hound’s-tongue (cynoglossa), then later amends to the narrow-leaved plantain—perhaps our Plantago lanceolate, the plantains with more strap-like leaves and flowers resembling petite cylinders with white tutus—and then encourages you to indulge its raw and cooked edible-ness. All of these cures require the pounding of this plant into something: wine for snakebites, water for fever, and oil for hearing (drinking or dripping the latter as apt), yet, interestingly, its efficacy against snakebites is left uncommented on, whereas against fever, it assures a cure, and against poor hearing, it promotes how “it will help in a wonderful manner.”◊◊

Whether plantains are a panacea, I’ll leave to the judgment of others. However, there are numerous medical articles about testing it for a whole number of therapeutic and pharmaceutical ends (the first two journal pieces I found flatly assert that “Modern pharmacological studies have proven some of [its] traditional applications”), and it is clear that along with its gustative bite (quite bitter, with a more umami or mushroomy aftertaste) it is quite generous in its nutritional profile.‡ Eating the young leaves in salads or boiling the older ones is mentioned most often, although can also be steeped for a tisane; the fresh flower heads can be tossed in stir-fries and, if one has the patience to collect its tiny, oily seeds, they can be ground into a rich flour.‡‡

Another species of the Plantago genus, P. media, or the hoary plantain, was introduced to the north-eastern United States from central and western Europe and appears in the 1920-30’s ethnobotany notes of Huron Smith as a medical plant used by the Native American Winnebagos who would finely chop the leaves to make a poultice to heat old sores, and additionally feed a little to cure unwell horses.∆ Smith’s research on the Menomini Native Americans documents the use of the leaves of Plantago major and its paler relation, P. rugelii (also differentiated, barely, by a slight reddish tinge on its petioles), warmed and bandaged on skin, to treat swellings and infections. In a self-experiment, Smith reported on his own swollen and infected hand clearing drastically in the course of one day after profuse sweating, although went on to note more dismissively that “Plantain has been thought by the white man to possess curative powers in many diseases, although it is really a very feeble remedy.”∆∆ Smith repeats the story of his own experience and elaborates his nevertheless skeptical opinion of Plantago (“feeble,” but “ascribed potency in many diseases by eclectic practioners”) when later reporting that the Ojibwe native Americans of the Wisconsin area also use plantain leaves, soaked in warm water and then bound on bruises, sprains, or sores, widely soothing burns, scalds, bee stings, and snake bites, as well as using its ground root to ward off snakes.∆ ∆ ∆ Plantain’s benefit for bleeding and burns is twice further affirmed in the 1970’s, first in the American Encyclopedia of Medicinal Herbs, and then in the British Encyclopedia of Herbs and Herbalism.◊

The use of plantain against snakes has a long, but less convincing, history. The Old English Herbarium instructs one who is suffering snake bites, quartan fever (malaria), or poor hearing, to seek what it first identifies as hound’s-tongue (cynoglossa), then later amends to the narrow-leaved plantain—perhaps our Plantago lanceolate, the plantains with more strap-like leaves and flowers resembling petite cylinders with white tutus—and then encourages you to indulge its raw and cooked edible-ness. All of these cures require the pounding of this plant into something: wine for snakebites, water for fever, and oil for hearing (drinking or dripping the latter as apt), yet, interestingly, its efficacy against snakebites is left uncommented on, whereas against fever, it assures a cure, and against poor hearing, it promotes how “it will help in a wonderful manner.”◊◊

Whether plantains are a panacea, I’ll leave to the judgment of others. However, there are numerous medical articles about testing it for a whole number of therapeutic and pharmaceutical ends (the first two journal pieces I found flatly assert that “Modern pharmacological studies have proven some of [its] traditional applications”), and it is clear that along with its gustative bite (quite bitter, with a more umami or mushroomy aftertaste) it is quite generous in its nutritional profile.‡ Eating the young leaves in salads or boiling the older ones is mentioned most often, although can also be steeped for a tisane; the fresh flower heads can be tossed in stir-fries and, if one has the patience to collect its tiny, oily seeds, they can be ground into a rich flour.‡‡

Untitled, by Johann Hieronymus Kniphof (1704-1763), Acad. Caes. Nat. Cur. Coll. Botanica in originali pharmaceutica, das ist (1733), Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, D.C..

Untitled, by Johann Hieronymus Kniphof (1704-1763), Acad. Caes. Nat. Cur. Coll. Botanica in originali pharmaceutica, das ist (1733), Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, D.C..

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

† † † Anne Van Arsdall, Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine, chapter five: “A New Translation of the Old English Herbarium” (New York: Routledge, 2002), 120, 143, 145. On “arniglosa,” cf., the Old English Plant Names page, available ~~HERE~~.

†††† Ruth Binney, Plant Lore and Legend: The Wisdom and Wonder of Plants and Flowers Revealed (Garden City, NY: Dover Publications, 2016), 96.

∆ Kelly Kindscher and Dana P. Hurlburt, “Huron Smith’s Ethnobotany of the Hocak (Winnebago),” Economic Botany 52, 4 (1998): 352-72, 363, 368 (an introduction to, commentary on, and editing of Huron Smith’s field notes for the “Ethnobotany of the Winnebago”).

∆ ∆ Huron H. Smith, Ethnobotany of the Menomini Indians (Westport, CN: Greenwood Press, 1923, reprint 1970), 46-47.

∆ ∆ ∆ Huron H. Smith, Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians (Milwaukee, WI: Order of the Board of Trustees, Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee, 1932), 380-81, 431.

◊ Joseph Kadans, Encyclopedia of Medicinal Herbs (New York: Arco Publishing Co., Inc., 1973), 165-66; Malcolm Stuart, ed., The Encyclopedia of Herbs and Herbalism (London: Orbis Publishing, 1979), 66.

◊◊ Anne Van Arsdall, Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine, chapter five: “A New Translation of the Old English Herbarium” (New York: Routledge, 2002), 130, 193.

‡ Y. Najafian, S. S. Jamedi, M. K. Farshchi, and Z. Feyzabadi, “Plantago major in Traditional Persian Medicine and modern phytotherapy: a narrative review,” Electronic Physician 10, 2 (Feb. 2018): 6390-99, available ~~HERE~~; S. Gonçalves and A. Romano, “The Medicinal Potential of Plants from the Genus Plantago (Plantaginaceae),” Industrial Crops and Products 83 (May 2016): 213-26, available ~~HERE~~.

‡‡ Many sources make mention, but the Canadian Wildlife Federation page includes interesting recipes, available ~~HERE~~.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

† † † Anne Van Arsdall, Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine, chapter five: “A New Translation of the Old English Herbarium” (New York: Routledge, 2002), 120, 143, 145. On “arniglosa,” cf., the Old English Plant Names page, available ~~HERE~~.

†††† Ruth Binney, Plant Lore and Legend: The Wisdom and Wonder of Plants and Flowers Revealed (Garden City, NY: Dover Publications, 2016), 96.

∆ Kelly Kindscher and Dana P. Hurlburt, “Huron Smith’s Ethnobotany of the Hocak (Winnebago),” Economic Botany 52, 4 (1998): 352-72, 363, 368 (an introduction to, commentary on, and editing of Huron Smith’s field notes for the “Ethnobotany of the Winnebago”).

∆ ∆ Huron H. Smith, Ethnobotany of the Menomini Indians (Westport, CN: Greenwood Press, 1923, reprint 1970), 46-47.

∆ ∆ ∆ Huron H. Smith, Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians (Milwaukee, WI: Order of the Board of Trustees, Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee, 1932), 380-81, 431.

◊ Joseph Kadans, Encyclopedia of Medicinal Herbs (New York: Arco Publishing Co., Inc., 1973), 165-66; Malcolm Stuart, ed., The Encyclopedia of Herbs and Herbalism (London: Orbis Publishing, 1979), 66.

◊◊ Anne Van Arsdall, Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine, chapter five: “A New Translation of the Old English Herbarium” (New York: Routledge, 2002), 130, 193.

‡ Y. Najafian, S. S. Jamedi, M. K. Farshchi, and Z. Feyzabadi, “Plantago major in Traditional Persian Medicine and modern phytotherapy: a narrative review,” Electronic Physician 10, 2 (Feb. 2018): 6390-99, available ~~HERE~~; S. Gonçalves and A. Romano, “The Medicinal Potential of Plants from the Genus Plantago (Plantaginaceae),” Industrial Crops and Products 83 (May 2016): 213-26, available ~~HERE~~.

‡‡ Many sources make mention, but the Canadian Wildlife Federation page includes interesting recipes, available ~~HERE~~.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Gareth Richards’ Weeds best identifies two reasons to praise the sometimes mundane plantain; first, he calls plantain a “compacted soil specialist,” being “one of those plants you can drive over and it will barely notice,” in fact, you will find it most often in the most trampled areas, and since “Compaction does terrible things to soil, literally squeezing the air and life out of it – plantain is nature’s rescue remedy, as its tough fibrous roots simultaneously break up compressed layers while protecting the soil from future erosion,” in return—and thus offering the second reason to well regard this little weed—plantain thus gains “quantities of minerals such as calcium and sulphur, adding to its health-giving qualities when consumed” by humans and grazing animals alike, for it is also “rich in vitamins A, C, and K.” He delineates a further reason to appreciate plantain, beyond, too, its long known medical properties, noting that some of its varieties are, in fact, rather interesting ornamentally: P. major ‘Rubrifolia’ and ‘Rosularis,’ often called ‘rose plantains,’ have striking red wine colored leaves, and ‘Bowles’ Variety’ bears unusual green bracts rather than its normal flowers—all of which can serve as slug-deterring hosta substitutes.‡‡‡

I have identified various mentions of wildlife and grazing animals happily nibbling your leaves and flowers (groundhogs, rabbits, deer, cattle, sheep), birds benefitting from your oil-rich seeds (cardinals and some sparrows), some insects (including the two-striped grasshopper), but the most extensive biodiversity list seems to be butterflies and moths of the Lepidoptera order that use Plantago for host plants.» Unfortunately, though, you can also play host to various plant viruses, including tobacco mosaic, aster yellows, beet curly top, beet yellows, tobacco streak, and tomato spotted wilt.»» Nevertheless, your benefits and interest outweigh, for me, any revulsions from the weed-eradication factions.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

‡‡‡ Gareth Richards, Weeds: The Beauty and Uses of 50 Vagabond Plants (London: Royal Horticultural Society and Welbeck Publishing Group, 2021), 136-37.

» Cf., Illinois Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; The Natural History Museum, London, HOSTS database, available ~~HERE~~.

»» Richard Dickinson and France Royer, Weeds of North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 538-39.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thus, let me return, at the end, to the aesthetic quality of the little plantain with which I began.

I have identified various mentions of wildlife and grazing animals happily nibbling your leaves and flowers (groundhogs, rabbits, deer, cattle, sheep), birds benefitting from your oil-rich seeds (cardinals and some sparrows), some insects (including the two-striped grasshopper), but the most extensive biodiversity list seems to be butterflies and moths of the Lepidoptera order that use Plantago for host plants.» Unfortunately, though, you can also play host to various plant viruses, including tobacco mosaic, aster yellows, beet curly top, beet yellows, tobacco streak, and tomato spotted wilt.»» Nevertheless, your benefits and interest outweigh, for me, any revulsions from the weed-eradication factions.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

‡‡‡ Gareth Richards, Weeds: The Beauty and Uses of 50 Vagabond Plants (London: Royal Horticultural Society and Welbeck Publishing Group, 2021), 136-37.

» Cf., Illinois Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; The Natural History Museum, London, HOSTS database, available ~~HERE~~.

»» Richard Dickinson and France Royer, Weeds of North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 538-39.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thus, let me return, at the end, to the aesthetic quality of the little plantain with which I began.

|

In his remarkable nature study, “Das große Rasenstück” (left), Albrecht Dürer clearly shows greater plantain [Plantago major], dandelion [Taraxacum], and tall, seeding grasses, from their roots to their flowery tips. The identifications of these grasses have been proposed as cock’s-foot or orchard grass [Dactylis], creeping bent grass [Agrostis], Kentucky bluegrass or smooth meadow-grass [Poa pratensis]; the work’s two other pictured plants: in the front right, perhaps a wisp of leaf of a yarrow [Achillea millefolium], and, in the rear left, a few sprigs rising up of what Richard Mabey in his fantastic book Weeds proposes to be burnet-saxifrage [Pimpinella saxifrage].*) ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ * Richard Mabey, Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants (New York: Harper-Collins, 2010), 57. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ |

|

While less naturalistically rendered, cut out of its own environs, an equally horticulturally-attentive work is this fine color etching of plantain from 1774, credited to a M. Bouchard (pictured to the right)* -- I hesitate as to whether this is monsieur Jean Bouchard, the French expatriate publisher in Italy in the mid-to-late 1700’s, or perhaps an engraving by his daughter Maddalena Bouchard, especially known for her etchings of exotic birds.** ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ * M. Bouchard, color etching, 1774, catalogued at the Wellcome Collection, available ~~HERE~~. ** Perrin Stein, Charlotte Guichard, Rena M. Hoisington, and Elizabeth M. Ruby, Artists and Amateurs: Etching in 18th-century France (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013), 42-43. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Finally, two notably different but still clearly plantain illustrations from the 18th century: |

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Above, left: Plantain, [Botanical manuscript of 450 watercolors of flowers and plants]. approximately 1740. RARE-FOLIO QK98.2 .B683 1740. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, D.C. Available ~~HERE~~.

Above, right: Plantin, Collection of seventy-eight water color plates of plants. [18th century?]. RARE RBR N-2-1. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, D.C. Available ~~HERE~~.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Above, left: Plantain, [Botanical manuscript of 450 watercolors of flowers and plants]. approximately 1740. RARE-FOLIO QK98.2 .B683 1740. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, D.C. Available ~~HERE~~.

Above, right: Plantin, Collection of seventy-eight water color plates of plants. [18th century?]. RARE RBR N-2-1. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, D.C. Available ~~HERE~~.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

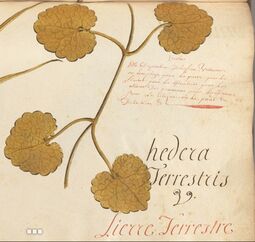

2)

Creeping Charlie (Glechoma hederacea):

Creeping Charlie, oh my, you are known by so many wonderful common names: creeping jenny, cat’s foot, alehoof and tunhoof (from hofe, Old English for ‘herb;’ ‘tunning’ was a mashing and fermenting of a brew), run-away-robin, ground-ivy, gill-over-the-ground or gill-go-by-the-ground, and the best: Devil’s candle-stick. You wildly, widely stretching weed, rhizomes racing and stems clonally rooting, mat-making but also somewhat lovely weed, with your ruffly fan-shaped leaves that betray your mint-family relations when crushed and your sweetly petite lavender and violet flowers the early bees quite enjoy. Native to Europe and northern Asia, with your presence in North American first reported in 1829, you were once used in making ale (a superb clarifier and flavoring) and replacing rennet in cheesemaking, treating so many bodily woes—Galen, around the second century, knew your aid for treating inflamed eyes; others said how good you were for pains, especially in the head, ridding one of coughs and inflammations; and an early 1930’s American herbal touted you as a superb “stimulant, tonic and pectoral, and is useful in many conditions,” notably “very beneficial in lead-colic, [so] painters sometimes make use of it,” plus certainly how your “fresh juice snuffed up the nose often relieve[s] nasal congestion and headache”—and, supposedly, according to the Tennessee Native Plant Society’s guide, “helping those who drank it to extend their lives,” besides otherwise spicing up salads and making the honey from bees who sip your nectar so, so sweet, no matter some suspicions as to your toxicity (namely, the massive Weeds of North America tome reports that, ingested in large quantities, Glechoma hederacea may be toxic to horses, but reports no evidence concerning other livestock, instead noting that it is more often deemed “a nuisance weed in turf”).* Say what they like, those who call you a nuisance, even when you invade my garden beds, I’ll just gently curb you back, as you delight my bees and make my backyard an utterly lovely greenscape—so, so much preferable to dull grass—as your scalloped fans are the brightest, crispest shade of lime green, providing perfect counterbalance, and thus harmony, with the yard’s other dominate leaves: the cadmium hearts of violets and British racing green strawberries.

Creeping Charlie, oh my, you are known by so many wonderful common names: creeping jenny, cat’s foot, alehoof and tunhoof (from hofe, Old English for ‘herb;’ ‘tunning’ was a mashing and fermenting of a brew), run-away-robin, ground-ivy, gill-over-the-ground or gill-go-by-the-ground, and the best: Devil’s candle-stick. You wildly, widely stretching weed, rhizomes racing and stems clonally rooting, mat-making but also somewhat lovely weed, with your ruffly fan-shaped leaves that betray your mint-family relations when crushed and your sweetly petite lavender and violet flowers the early bees quite enjoy. Native to Europe and northern Asia, with your presence in North American first reported in 1829, you were once used in making ale (a superb clarifier and flavoring) and replacing rennet in cheesemaking, treating so many bodily woes—Galen, around the second century, knew your aid for treating inflamed eyes; others said how good you were for pains, especially in the head, ridding one of coughs and inflammations; and an early 1930’s American herbal touted you as a superb “stimulant, tonic and pectoral, and is useful in many conditions,” notably “very beneficial in lead-colic, [so] painters sometimes make use of it,” plus certainly how your “fresh juice snuffed up the nose often relieve[s] nasal congestion and headache”—and, supposedly, according to the Tennessee Native Plant Society’s guide, “helping those who drank it to extend their lives,” besides otherwise spicing up salads and making the honey from bees who sip your nectar so, so sweet, no matter some suspicions as to your toxicity (namely, the massive Weeds of North America tome reports that, ingested in large quantities, Glechoma hederacea may be toxic to horses, but reports no evidence concerning other livestock, instead noting that it is more often deemed “a nuisance weed in turf”).* Say what they like, those who call you a nuisance, even when you invade my garden beds, I’ll just gently curb you back, as you delight my bees and make my backyard an utterly lovely greenscape—so, so much preferable to dull grass—as your scalloped fans are the brightest, crispest shade of lime green, providing perfect counterbalance, and thus harmony, with the yard’s other dominate leaves: the cadmium hearts of violets and British racing green strawberries.

|

* Cf., Richard Mabey, Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants (New York: Harper-Collins, 2010), 71; Richard Dickinson and France Royer, Weeds of North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 438-39; Joseph E. Meyer, The Herbalist (Hammond, IN: Hammond Book Company, 1934), 114-15; Dennis Horn, Tavia Cathcart, Thomas E. Hemmerly, and David Duhl, Wildflowers of Tennessee the Ohio Valley and the Southern Appalachians (Auburn, WA: Lone Pine Publishing, 2018), 260; Malcolm Stuart, ed., The Encyclopedia of Herbs and Herbalism (London: Orbis Publishing, 1979), 197-98.

|

|

To the right: Creeping Charlie, identified as hedera terrestris, ground ivy, illustrated in: [Botanical manuscript of 450 watercolors of flowers and plants], dated approximately 1740, RARE-FOLIO QK98.2 .B683 1740, at Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, D.C.. Available ~~HERE~~. |

“When stems recline on the soil surface or grow below ground, they have no need to spend energy or nutrients on the construction of metabolically expensive strengthening tissues. Thus, they are able to direct all of their resources into a burst of rapid, primary growth that carries the leaves into more favorable illumination.”

--Brian Capon, Botany for Gardeners (Timber Press), 111.

3)

|

Smilax Spp. (e.g., S. rotundifolia, common or roundleaf greenbrier or S. bona-nox, a.k.a., saw greenbrier or the more humorous tramp’s trouble)--oh, you rhizomatically growing woody and up to 20’ vine, you who crawls or climbs by tendrils (aided by hooked thorns), with cruel, cruel thorns up to 9mm, your first pale olive-ish then glossy green leaves round to heart shaped or speckled in lighter green, with 3-20 umbels of greenish-white flowers from April-August, and bluish-black berry ripe in September. You are so hard to get rid of, you survive droughts and your rhizomes survive fires, and you just pop up all over--not to mention your native range spanning the eastern half of the U.S. up to northern Ontario, with the S. bona-nox more likely found in southeastern U.S. down through Bermuda and Mexico--and you have thorns to scare the devil.

Yet, your young shoots can be cooked like asparagus, your young leaves and tendrils can be eaten raw or cooked; and your roots have a natural gelling or thickening agent, and those from some of your species (e.g., S. ornata, S. domingensis) have been used to make sarsaparilla or root beers. Not to mention that your fruits and leaves provide food for many animals (e.g., birds, deer, butterflies) and your dense thickets provide shelter (e.g., small animals).* Most beguilingly, your name “Smilax” comes from the Greek myth of the nymph Smilax, who was transformed into a bramble vine, after her failed, unfulfilled love of Crocus (his fate, kinder?)--though, admittedly, Ovid’s Metamorphoses only mentions that “Crocus, and Smilax may be turn’d to flow’rs.”**) |

4)

“As long as favorably lit places are open for encroachment, the relentless advance of perennial stoloniferous and rhizomatous species may continue indefinitely.”

--Brian Capon, Botany for Gardeners (Timber Press), 111.

5)

|

Porcelainberry (Ampelopsis brevipedunculata): -- while sometimes called porcelain vine or amur peppervine, you more closely imitate grapevine with your deeply lobed, three to five times, leaves bearing toothed margins on vines that can climb 15-20 feet by tendrils, and your small greenish-white flowers in mid-summer that develop porcelain-looking fruits in fall in whites to yellows to pastel blues, greens, and purple, as if miniature and more uniquely colored grapes—though, while you are also in the Vitaceae (grape) family, your genus (recognizing your imitative powers in its combination of the Greek ampelos and opsis, vine and likeness) is different from that of our traditional table grapes. It may be your visual trickery and, while certainly not tasty (in fact, mildly poisonous) your certainly beautiful berries, that explain why you can still be found rather widely for sale (or your ability to adapt to most soils and thrive in sun or shade, albeit the latter restricts your flowering); however, it is your drastically invasive properties that should restrain our purchase and encourage our plucking you out should you mysteriously appear. Your appearance here was certainly as a volunteer, yet

|

so craftily placed at the foot of a tall ornamental garden pole—likely ‘donated’ by one of my feathered or furred visitors. Your fruits may provide birds and small animals a small snack, but as a non-native (your origin is in northeast Asia), you do not serve as a host or food source to any other garden residents.*

* Cf. , “Invasive Weeds of the Appalachian Region,” University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture, Extension Service, publication PB1785, accessed May 16, 2021, and available ~~here~~; the Tennessee Invasive Plant Council, for its emerging invasive threat demarcation ~~HERE~~; The Missouri Botanical Garden, available ~~HERE~~.

* Cf. , “Invasive Weeds of the Appalachian Region,” University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture, Extension Service, publication PB1785, accessed May 16, 2021, and available ~~here~~; the Tennessee Invasive Plant Council, for its emerging invasive threat demarcation ~~HERE~~; The Missouri Botanical Garden, available ~~HERE~~.

6)

The root of another, kinder species, the Diervilla lonicera -- also called bush honeysuckle, but an eastern North American native -- was documented by the ethnobotanist Huron Smith as being cooked and used for a tea to aid urination and clean a woman after child birth by the Winnebago Native Americans.† In his studies of the Menomini Native Americans, bush honeysuckle was also made into a tea used to cure senility and as a mild diurient, and also notes that “Eclectics among the white men have used the fruit for its emetic and cathartic properties. This plant is valued by them as a diuretic and as a means to relieve itching.”†† And in another work on the Wisconsin Ojibwe Native Americans, bush honeysuckle, again, was identified as “their most valued urinary remedy,” although its root would be mixed with ground pine (Lycopodium obscurum).†††

* Cf., “Invasive Weeds of the Appalachian Region,” University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture, Extension Service, publication PB1785, ~~HERE~~, accessed May 16, 2021; Minnesota Wildflowers page on L. maackii, available ~~HERE~~; North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, on L. japonica, available ~~HERE~~; Minnesota Wildflowers page on available ~~HERE~~; North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, on L. flava, available ~~HERE~~ or the Missouri Botanical Garden page, available ~~HERE~~; the Minnesota Wildflowers page on L. dioica, available ~~HERE~~; the Missouri Botanical Garden page on diervilla lonicera, available ~~HERE~~; and the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center page on L. sempervirens, available ~~HERE~~.

** “Invasive Weeds of the Appalachian Region,” University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture, Extension Service, pub.: PB1785, accessed May 16, 2021, available ~~here~~

*** On L. maackii, cf., Richard Dickinson and France Royer, Weeds of North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 228; the Missouri Botanical Garden page, available ~~HERE~~; the North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, available ~~HERE~~; the Minnesota Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; the Illinois Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; the Invasives page, available ~~HERE~~; the Invasive Plant Atlas of the U.S., available ~~HERE~~; the CABI Invasive Species Compendium page, available ~~HERE~~; the Ohio Environmental Council blog page, available ~~HERE~~;

† Kelly Kindscher and Dana P. Hurlburt, “Huron Smith’s Ethnobotany of the Hocak (Winnebago),” Economic Botany 52, 4 (1998): 352-72, 361 (an introduction to, commentary on, and editing of Huron Smith’s field notes for the “Ethnobotany of the Winnebago”). Also cf. the Missouri Botanical Garden page for information on this bush honeysuckle native, available ~~HERE~~.

†† Huron H. Smith, Ethnobotany of the Menomini Indians (Westport, CN: Greenwood Press, 1923, reprint 1970), 27.

††† Huron H. Smith, Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians (Milwaukee, WI: Order of the Board of Trustees, Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee, 1932), 360, 375.

* Cf., “Invasive Weeds of the Appalachian Region,” University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture, Extension Service, publication PB1785, ~~HERE~~, accessed May 16, 2021; Minnesota Wildflowers page on L. maackii, available ~~HERE~~; North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, on L. japonica, available ~~HERE~~; Minnesota Wildflowers page on available ~~HERE~~; North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, on L. flava, available ~~HERE~~ or the Missouri Botanical Garden page, available ~~HERE~~; the Minnesota Wildflowers page on L. dioica, available ~~HERE~~; the Missouri Botanical Garden page on diervilla lonicera, available ~~HERE~~; and the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center page on L. sempervirens, available ~~HERE~~.

** “Invasive Weeds of the Appalachian Region,” University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture, Extension Service, pub.: PB1785, accessed May 16, 2021, available ~~here~~

*** On L. maackii, cf., Richard Dickinson and France Royer, Weeds of North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 228; the Missouri Botanical Garden page, available ~~HERE~~; the North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, available ~~HERE~~; the Minnesota Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; the Illinois Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; the Invasives page, available ~~HERE~~; the Invasive Plant Atlas of the U.S., available ~~HERE~~; the CABI Invasive Species Compendium page, available ~~HERE~~; the Ohio Environmental Council blog page, available ~~HERE~~;

† Kelly Kindscher and Dana P. Hurlburt, “Huron Smith’s Ethnobotany of the Hocak (Winnebago),” Economic Botany 52, 4 (1998): 352-72, 361 (an introduction to, commentary on, and editing of Huron Smith’s field notes for the “Ethnobotany of the Winnebago”). Also cf. the Missouri Botanical Garden page for information on this bush honeysuckle native, available ~~HERE~~.

†† Huron H. Smith, Ethnobotany of the Menomini Indians (Westport, CN: Greenwood Press, 1923, reprint 1970), 27.

††† Huron H. Smith, Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians (Milwaukee, WI: Order of the Board of Trustees, Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee, 1932), 360, 375.

7)

|

Privet (Ligustrum sinense):

In the Oleaceae family, Ligustrum are nearly all shrubs and can be found worldwide; L. sinense is one of nearly 50 species, and certainly the one spoken of with the most ire. The genus name is simply Latin for privet, and was officially recognized by Linnaeus in 1753; while it would have been most apt, most dictionaries dispute any connection of its common name to “private.”* Well-clipped privet is iconic—as topiary or the classic boxy edge, hedges are the “unofficial emblem of Great Britain” according to a fairly recent Smithsonian article, “They are a charmed circle drawn around family and self,” and do certainly populate every memory and dreaming I have of fine gardens across the Continent.** But I am in the States’ mid-south and too plagued by days of 105º F heat indexes and yards full of invisible, thoroughly demonic chiggers to keep my privet all pretty. Instead, it is headstrong: utterly unhappy being a clipped monochrome between properties (just in the front, running two thirds of the way from house to street—any more and it’s too un-neighborly), it stays twiggy when shorn and so invites every elm baby and bindweed to join it, and then runs off and pops up like little leafy pikes across the yard, in the beds, in every nook and cranny one doesn’t patrol endlessly. It is an extremist interpretation of Isaac Ware’s 1756 advice in A Complete Body of Architecture that the most cheerful and pleasing landscape design is that with wild hedges, those “mimicking savage nature, only in a state of more variety.”*** And it is actually most pleasing as such, for no neatly clipped privet hedge is permitted to bloom and when one of those unpatrolled upstarts suddenly erupts in a froth of white flowers, the humid nights are as magically perfumed as the jasmined Persian gardens of storybooks. Thus privet is another ambiguous case: a prized shrub or invasive weed? In Tennessee and 13 other states, as well as by the U.S. Forest Service, its threat level is established: invasive species. Despite its reported low seed germination rate (only 5-27%), birds enjoy and spread the seeds widely, while old stumps and roots can readily sprout new plants leading it to be what the Tennessee Invasive Plant Council describes as “Aggressive and troublesome invasives, often forming dense thickets … thus gaining access to forests, fields, and right-of-ways,” and as capable of growing up to five to seven thickly leaved meters, privet can easily shade out and kill native species and destroy biodiverse areas.† While called a shrub, the privet strays about my yard far more resemble small trees, with pale, smooth bark and dark pine to nearly phthalo green, petite oval, and oppositely arranged leaves. Its flowers are white, very small but clustered on panicles dangling daintily at the ends of its stems. While, for me, their fine fragrance is reminiscent of some synthesis of jasmine, paper-whites, and lily of the valley, the North Carolina Extension Service describes the flowers as “fetid,” and productive of “an odor that can be offensive to many people.” After, its hundreds of small fruits then turn a dark bluish black, staying on the bush all winter, if not devoured by the birds first. Privet was introduced to the U.S. from China around 1852 as an ornamental shrub, and proved superb to tolerating air pollution and diverse, including poor, environmental conditions while remaining a hardy, mostly evergreen, attractive shrub and useful, wind-blocking hedge plant.†† Oh, privet, you invasive yet attractive rascal. The Smithsonian article also cited John Wright’s hedge history to estimate that Great Britain has about 435,000 miles of hedgerows, and while not just privet, of course, it sometimes feels that it is privet alone taking such mileage about my property—but when the summer’s dog days are here, the nights’ din of tree frogs and cicadas overwhelming, I want the stray privets’ perfume.††† |

* Michael L. Charters’ compilation of plant names’ histories, available ~~HERE~~; the OED reputedly denies it directly, while those such as Merriam-Webster simply date it prior to the 12th c. and origins unknown, whereas the Online Etymology Dictionary suggests a potential connection to “prime” (for the last, cf. ~~HERE~~).

** Peter Ross and Kieran Dodds, “How Hedges Became the Unofficial Emblem of Great Britain,” Smithsonian (Nov. 20, 2020), available ~~HERE~~. *** Isaac Ware, A Complete Body of Architecture (London: T. Osborne and J. Shipton, 1756), 645; also extracted in Elizabeth Kryder-Reid, “History of Early American Landscape Design,” A Project of the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, National Gallery of Art, available ~~HERE~~. † Tennessee Invasive Plant Council page, available ~~HERE~~; also, for statewide and worldwide invasive listings, cf. Invasive Plant Atlas page, available ~~HERE~~, the USDA National Invasive Species Information Center page, available ~~HERE~~, and CABI, Invasive Species Compendium, available ~~HERE~~; There is an additional report of privet dominated forests not destroying the bug population and its diversity, although likely decreasing local bee populations, cf. ~~HERE~~. ††Cf., North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox page, available ~~HERE~~; Tennessee Invasive Plant Council page, available ~~HERE~~; University of Florida Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants page, available ~~HERE~~; Carolina Nature page, available ~~HERE~~. ††† Peter Ross and Kieran Dodds, “How Hedges Became the Unofficial Emblem of Great Britain,” Smithsonian (Nov. 20, 2020), available ~~HERE~~. |

8)

|

Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), member of the Vitaceae (grape) family, sometimes also called Victoria creeper, five-leaved ivy, five-finger, or woodbine (the last, technically, more apt to western U.S.’ non-ariel-rooted P. vitacea). You eastern and central U.S. native rhizomatic woody vine with your peculiar way of climbing by adhesive disks on short branches, but capable of clambering up or out 40 feet, your dramatic five elliptical toothy-edged and palmately arranged leaflets that eagerly greet fall in red, mauve, and purple, and your petite yellow-green flower clusters that develop light honeydew cum deep merlot mini-grape-looking but poisonous berries—you are lovely and utterly horrendous at once. Such vigor you have, not caring if the soil is luscious or terrible, the sun bright and bold or barely there, and spanning zones five to 11. Little kids are counseled by the refrains of “leaves of three (i.e., poison ivy), let it be; leaves of five (i.e., Virginia creeper), let it thrive,” but thrive—you do it too well about my yard, attesting to the caution The Spruce offers, that while you are native, and “cannot, technically, be listed as an invasive plant,” you are one “that spreads out of control,” “said to be ‘aggressive’.” Gardening sites love to recommend you: for your sizable, speedy spread, spring lime and darkening forest summer greens to autumnal garnet blazes, for your tolerant nature, your gentler disposition to mortar (although you do leave bare polka dots on my stained

|

Virginia Creeper, before much creeping

Virginia Creeper, before much creeping

wood fence), and especially the zealous favor spread on you by chickadees and mockingbirds, nuthatches, finches, catbirds and flycatchers, thrushes and tanagers, swallows and vireos, warblers and woodpeckers, not to mention hosting the caterpillars of several sphinx moths (the Sphingidae, notably the aptly named Virginia Creeper sphinx, Abbott’s, Pandora, and the White-lined*)—even if your berries are dreadfully poisonous to pets and humans, and your tissues carry skin-irritating oxalate crystals’ raphides. After choking out a neighbor’s no one’s zone’s scruffy brush and volunteered elms, you hopped—coated, actually—my tall wooden fence and plant-smiled at your fortune of finding caged-in raised beds to swag and swaddle, then stretch out from, competing heartily against the violets, Euonymous, and ivy to prove you are as effective a groundcover as a climber. You are lucky your fall show is so nice and so many of the most charming birds here enjoy you.**

* Douglas W. Tallamy, Bringing Nature Home: How you can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2021), 324-26.

** Brian Capon, Botany for Gardeners (Portland: Timber Press, 2005), 137, 107; Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center page, available ~~HERE~~; Gardening Know How page, available ~~HERE~~; The Spruce page, available ~~HERE~~; Colorado State University Guide to Poisonous Plants, available ~~HERE~~; Minnesota Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; Missouri Botanical Garden page, available ~~HERE~~. |

9)

|

Wintercreeper (Euonymous fortunei), sometimes called climbing euonymus, or spreading euonymous—which I am tempted to elaborate to spreading-like-wild-fire-euonymous—was introduced from its native China as an ornamental in 1907 and is still freely promoted and planted as a mostly evergreen, fast-growing, dense perennial spreader superb for tough areas, but I consider it one of the most unruly weeds about my yard (and this, I have found, is not an uncommon view, as this euonymous has made it on the invasive species list for a dozen states plus Tennessee*). Commonly found in the eastern and central U.S. states, most especially Kentucky and Tennessee, (but also reported in Canada, Argentina, France, Germany, Poland, and of course throughout much of Asia,) especially around homes, through disturbed grounds, forested areas, and into grasslands. Sometimes maintaining a meter tall shrub-like form, more often its ‘creeper’ nature is to spread its viney arms out 20 plus feet and use its abundant aerial rootlets to climb up to 70 feet, quickly rooting when media is found. Its flowering-fruiting seed production is immense, too, with many birds and animals enjoying and thereby spreading its seed. Its seedlings erupt rampantly in all my garden beds and “yard” in the spring, from the sunniest and driest to the shadiest and wettest corners, and persist springing up here and there all summer long. Coupling its persistence and flexibility with its tendency to cover and smother anything in its path, it is quite a bane of my existence—yet, I must also admit to its possession of several very attractive features: its newest twiggy vines and leaves blare a bright lime green in pleasing contrast to its deep and dark, mostly opposite, small but broad and oval, and slightly under-turning adult leaves; its flowers are most petite, but striking clusters of unusual greenish-yellow cross-forming flowers whose darker green inner eye is marked with another

|

Euonymous' 'hairy' trunk

Euonymous' 'hairy' trunk

small cross from when its small pistils come; but most of all, it is the eye-catching seeds, their dangling papery pods which split to reveal gleaming fleshy seeds some color between a polished pumpkin and brightly red blushing tangerine. The bright and light green of its new growth turns, here, into a dark hunter, more so, nearly the ripest of artichoke-green, one touched with almost a blue and olive hue, although some cultivars have been bred to have purple-tinted or white to green-gold variegated leaves. While there is suspected human toxicity if eaten in large quantities—possibly due a glycoside—I have observed a wide range of birds, especially mockingbirds, red winged blackbirds, and orioles, feasting jovially on the berries. In addition to providing a dense scruff of cover for birds and bugs, from the hairy, tree-like stumps long ago planted along a rusty wire fence, its strong vines have aggressively woven themselves up, through, and over a scrubby brush-line of honeysuckles to securely form an endlessly active squirrel highway along my property line.**

honeysuckle & euonymous, new borns

honeysuckle & euonymous, new borns

* Tennessee Invasive Plant Council, available ~~HERE~~

** Cf., U.S.D.A. and U.F.S. Fire Effects Information System page, available ~~HERE~~; Tennessee Invasive Plant Council page, available ~~HERE~~ ; CABI Invasive Species Compendium, available ~~HERE~~ ; Native Plant Trust’s Go Botany page, available ~~HERE~~ ; Ohio Environmental Council page, available ~~HERE~~ ; North Carolina Extension Gardener page, available ~~HERE~~ .

** Cf., U.S.D.A. and U.F.S. Fire Effects Information System page, available ~~HERE~~; Tennessee Invasive Plant Council page, available ~~HERE~~ ; CABI Invasive Species Compendium, available ~~HERE~~ ; Native Plant Trust’s Go Botany page, available ~~HERE~~ ; Ohio Environmental Council page, available ~~HERE~~ ; North Carolina Extension Gardener page, available ~~HERE~~ .

10)

|

Ivy (Hedera helix): You are the cape cladding every stately old building in my imagination, and appropriately prove well-documented in medieval herbals. According to the good Old English Herbarium, you prove remarkable for stones in the bladder (eleven berries should be stewed in water that “will collect the stones in the bladder in a wondrous way and will destroy them and send them out through the urine”), pains in the spleen (the first attack requires three berries, the second needs five, then seven, nine, and so on, up to the tenth attack, each time drinking them daily in wine, unless there is a fever, as then warm water is a better medium), headaches (ivy and rose juice should be mixed in wine and rubbed on the face and temples), especially those from the sun (soft leaves pounded in vinegar are here prescribed for wiping on one’s face and head), healing wounds (simmered in wine) and poor hearing (with wine, and dripped in the ear), and “For evil-smelling nostrils” (poured into the nose).† (It also remarks on two other species ... so, if you happen to come unkindly across a spalangiones—some sort of venomous spider, although later described as a snake or scorpion††—and he doesn’t take it well, the resulting bite should be treated with hedera nigra, specifically, by drinking the juice of its roots.* While hedera crysocantes, is good for dropsy (the swelling of soft tissues).** In an American natural pharmacological text, The Herbalist, from 1934, English ivy’s leaves are both broadly and briefly described as a “stimulant, vulnerary, exanthematous and insecticide,” and its berries as an “emetic and cathartic.”**

“When you look at what ivy is, what it can do and how much life it supports, calling it a weed seems hugely ungrateful.”

-- Gareth Richards, Weeds: The Beauty and Uses of 50 Vagabond Plants (London: Royal Horticultural Society and Welbeck Publishing Group, 2021), 92. |

† Anne Van Arsdall, Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine, chapter five: “A New Translation of the Old English Herbarium” (New York: Routledge, 2002), 130, 193-94.

†† Ibid., 208. * Ibid., 130, 194. ** Ibid., 132. *** Joseph E. Meyer, The Herbalist (Hammond, IN: Hammond Book Company, 1934), 82. |

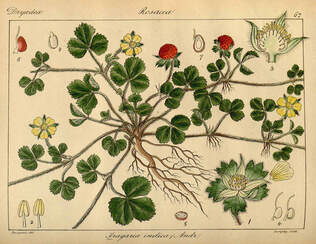

11)

|

Wild strawberry (Fraga, or Fragaria spp.) aids pain in the spleen or abdomen as well as asthma when served (more palatably than most of the Old English Herbarium’s other recipes) with honey and a little pepper in a drink.* The ethnobotanist Huron H. Smith reports the Ojibwe native Americans steeping its root—which they called ‘heart berry root’—to cure stomach aches, especially in babies; he further reports white people using it as an astringent and convalescent tonic for children with bowel or bladder concerns.** And, to cure another sort of ache, ethnobotanical sources report that Ireland had a tea of strawberry leaves said to cool “excessive ardour.”***

|

|

However, I learned that my lovely lawn-cover is not truly wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana), but the common but non-native mock or Indian Strawberry (Duchesnea indica, some sources include this in the Potentilla genus, specifically thus as P. indica)—an equally beautiful trailing perennial herb that closely resembles the other except for its having brilliantly sunny yellow flowers. Its genus was named in honor of the French strawberry expert Antoine Duchesne (1747-1827), and its species name identifying its hailing from India or the East Indies, or even occasionally China. It is common through much of the eastern U.S., including Tennessee, where it tends to bloom far longer than otherwise reported, stretching its April to June period more to March to August. Its berries are edible, but far more petite and seedy than one’s green grocer may carry, and hardly have any flavor, although the birds, squirrels, and chipmunks about the yard seem to enjoy them.†

Image: Fragaria indica, R. Wight, Spicilegium Neilgherrense (1846-1851), vol 1 (1846), t.62, available ~~HERE~~.

|

wild strawberry flower and fruit, encroached upon by creeping charlie

wild strawberry flower and fruit, encroached upon by creeping charlie

* Anne Van Arsdall, Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine, chapter five: “A New Translation of the Old English Herbarium” (New York: Routledge, 2002), 124, 168.

** Huron H. Smith, Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians (Milwaukee, WI: Order of the Board of Trustees, Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee, 1932), 384.

*** David E. Allen and Gabrielle Hatfield, Medicinal Plants in Folk Tradition: An Ethnobotany of Britain and Ireland (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2004), 146.

† Dennis Horn, Tavia Cathcart, Thomas E. Hemmerly, and David Duhl, Wildflowers of Tennessee the Ohio Valley and the Southern Appalachians (Auburn, WA: Lone Pine Publishing, 2018), 147-48.

** Huron H. Smith, Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians (Milwaukee, WI: Order of the Board of Trustees, Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee, 1932), 384.

*** David E. Allen and Gabrielle Hatfield, Medicinal Plants in Folk Tradition: An Ethnobotany of Britain and Ireland (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2004), 146.

† Dennis Horn, Tavia Cathcart, Thomas E. Hemmerly, and David Duhl, Wildflowers of Tennessee the Ohio Valley and the Southern Appalachians (Auburn, WA: Lone Pine Publishing, 2018), 147-48.

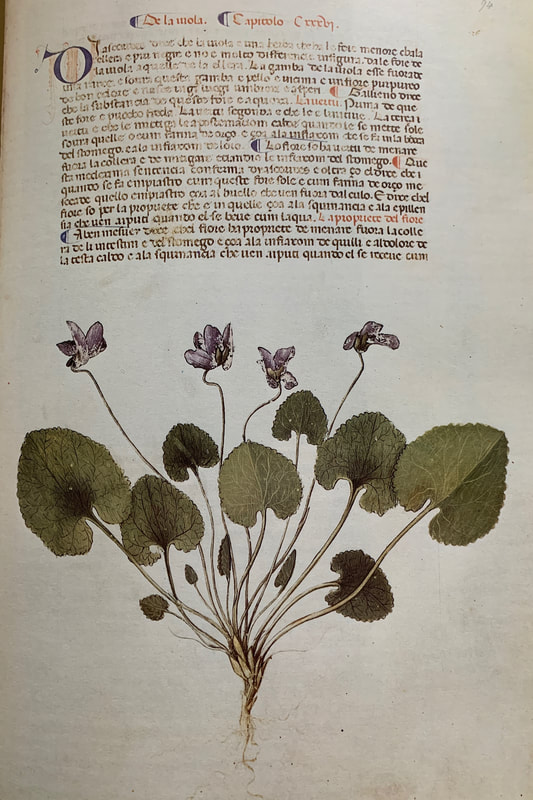

12)

|

Violets (Viola spp.)

Oh, miss violets, I love to see you in spring, and I do coddle you, you who are clustered and strewn so widely -- like rose petals in a romance novel -- across the lawns; your wonderfully regal purple velvets and varying chambrays all charmingly, coyly beguile me to leaving you all be ... but, I must ask you, why must you invade so ferociously my garden beds? |

Even if over prolific, violets may prove to have benefits beyond their beauty ... Hildegard of Bingen’s Cause et Cure (ca. 1151) reports that those with “firey eyes”—those that are “similar to a black cloud close to the sun,” and therefore typically healthy and clear, for they have “received them by nature from the warm south wind”—do occasionally suffer from eye impairments due “Dust and any bad stench,” thus, for those who “do not see well with them,” she prescribes a tripartite tincture of the juices of rose, fennel, and pansy blended into a little wine for washing the skin around the eyes in the evening.* Since “pansy” is frequently interchanged with “viola” and “violet,” the precise plant she intends is unclear, but a not-unfounded presumption is that this is not today’s frequently spring-planted hybrid Viola section Melanium, but, rather, the more field-common purple proliferates, Viola spp..

|

The Doctrine of Signatures is the medieval update of a late ancient theory that each plant served a purpose and bore a divinely given ‘signature’ identifying this purpose, for example the palely spotted leaves of Pulminaria resemble a sickly lung, hence the plant, commonly called lungwort, was to be used in treating lung ailments. Botanicals were prescribed for infirmities well beyond strictly bodily woes, too, including the relief of hexes and for many emotional disturbances. According to this philosophy, Dr. Thomas Johnson (the London botanist, apothecary, and 1630’s editor—and extender and occasional critic—of John Gerald’s Herball) speculated that the pansy (Viola) was so named for its being a general ‘panacea,’ although it was also called love-in-idleness and heartsease, and therefore was especially recommended for soothing heartache.† One will well recognize the name “love-in-idleness” from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream: “… yet marked I where the bolt of Cupid fell: it fell upon a little western flower before milk-white, now purple with love’s wound, and maidens call it love-in-idleness. …”†† Beyond bringing beauty to lawns and beds and aiding our sore hearts, violets play an important ecological role as host to various caterpillars, namely those of the Great spangled fritillary (Speyeria cybele), Meadow fritillary (Boloria bellona), and Variegated fritillary (Euptoieta claudia) butterflies.†††

|

* Margret Berger, ed., Hildegard of Bingen: On Natural Philosophy and Medicine: Selections from Cause et Cure (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1999), 108, 72. Further, grey or turbid eyes need fennel (mix with dew & wheat for the former, or egg white for the latter); ailing eyes “of various colors” need zinc carbonate mixed with pure white wine; black eyes need nightly patches of bread steeped in rue, honey, & wine; & white spots on corneas ought be treated sparingly over three nights with fresh ox bile (Ibid., 108-09).

† Ruth Binney, Plant Lore and Legend: The Wisdom and Wonder of Plants and Flowers Revealed (Garden City, NY: Dover Publications, 2016), 25-26.

†† William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 2.1, pp.459-63, collected in The Book of Magic: From Antiquity to the Enlightenment, trans./ed. Brian Copenhaver (New York: Penguin Books, 2015), 463.

††† Douglas W. Tallamy, Bringing Nature Home: How you can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2021), 118, 318-19.

† Ruth Binney, Plant Lore and Legend: The Wisdom and Wonder of Plants and Flowers Revealed (Garden City, NY: Dover Publications, 2016), 25-26.

†† William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 2.1, pp.459-63, collected in The Book of Magic: From Antiquity to the Enlightenment, trans./ed. Brian Copenhaver (New York: Penguin Books, 2015), 463.

††† Douglas W. Tallamy, Bringing Nature Home: How you can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2021), 118, 318-19.

|

The Violet

The Violet in her greenwood bower, Where birchen boughs with hazel mingle, May boast itself the fairest flower In glen, or copse, or forest dingle. Though fair her gems of azure hue, Beneath the dew-drop’s weight reclining; I’ve seen an eye of lovelier blue, More sweet through wat’ry lustre shining. The summer sun that dew shall dry, Ere yet the day be past its morrow; No longer in my false love’s eye Remain’d the tear of parting sorrow. --Sir Walter Scott (Published originally in the Edinburgh Annual Register, 1808; collected in volume IV of Ward’s The English Poets, ~~HERE~~) |

Image: Violet (Viola odorata) color plate, Serapion the Younger, Herbolario volgare, Padua, 1390-1400; held by British Library, MS Egerton 2020, reprinted in Wilfrid Blunt and Sandra Raphael, The Illustrated Herbal (London: Frances Lincoln Publishers, Inc).

13)

|

Speedwell (Veronica, e.g., V. officinalis, V. americana, but also looking similar to V. umbrosa or V. pedundularis (creeping speedwell)): you are also sometimes called just veronica, or birdseye and gypsyweed or brooklime, but your most common common name is said to come from ‘speed’s’ archaic meaning, ‘to thrive’*—and that you do! You are one of the few weeds I tend to always welcome, even if needing to sometimes violently reclaim an early spring bed from your profligate lushness. In fact, I wish your relative was just as rampant, the demure, ever-reliable garden perennial we also simply call Veronica (e.g., a ‘spike’ speedwell, like V. spicata and other hybrids), the usually fairly petite plant with brilliant purple to almost bluish spikes the bees and butterflies so love. With over 200 species in the Veronica genus (and the photographs of many different “mat-forming” or “ground-covering” or just “weedy” ones looking so very similar and all called speedwell),

|

it is a challenge to correctly identify which Veronica I have across my yard. It is the basic one, I want to say, the same I see all around here—and perhaps that impulse is why Weeds of North America identifies V. officinalis as a North American native, whereas most other resources identify it as a wide-spread and long U.S. established introduction from Europe and/or Asia, sometimes more specifically identifying origins, either like Plants for a Future’s broadening elaboration of “Europe, including Britain, from Iceland south and east to Spain, W. Asia, and the Caucasus,” or like NatureGate’s minute pinpointing of “rocky outcrops and light-filled hillside broad-leaved forests in southern Finland.”** (Attempting to learn more about this mystery, my google search instead declared it historical fiction, that is, it recommended Deanna Raybourn’s A Veronica Speedwell Mystery Series, the seventh installation available for preorder from Penguin Random House.) Pressing on, I discovered an agreed upon native, V. americana, ranges from Alaska, through most of Canada, and all of the continental U.S. except for the most southeasterly states from Louisiana to Florida. Its pictures look just as close to that in my beds as pictures for V. officinalis and a dozen others. It is petite, oval and minutely toothed opposite leaves along stems barely crawling to 10-30 cm away, its even more delicate spike-like raceme reaching barely three to six cm tall with tiny specks of deeply purple veined whiteish to pale blue to violet four-petaled flowers. Your flowers!, as the U.S. Forest Service’s ‘Plant of the Week’ highlight of you explains, you are one of the few flowers that “are bilaterally symmetrical, meaning that only a single plane of symmetry exists that will bisect the flower into equal, mirror-image halves,” that is, bearing the same sort of symmetry human faces more or less possess, or, again, that is “Veronica flowers resemble a human face when viewed front-on.”† In other words, I am not sure exactly who you are, but you appear in the spring, petite in stature and delicate in leaf, and flocked in the loveliest variations of blue, purple, and white petite flowers, not to mention being reputedly edible (the V. americana and V. beccabunga species reportedly two of the few tart but pleasant tasting species), an old medicinal cure-all, and as a tea, beneficial to allergies—so I declare you a native, grace you with the name wildflower, and, except when you overly blanket my attempting to awaken perennials, will let you be across my property.††

* For the etymology, cf., “Origin of Some Common Names of Plants compiled by Nina Curtis on behalf of The Tortoise Table,” available ~~HERE~~.

** Cf., for native status, Richard Dickinson and France Royer, Weeds of North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 543; versus the following identifying foreign origins: Native Plant Trust, available ~~HERE~~; Minnesota Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; Naturegate page, available ~~HERE~~.

†U.S. Forest Service Plant of the Week page, available ~~HERE~~.

†† Cf., Richard Dickinson and France Royer, Weeds of North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 543; Native Plant Trust, available ~~HERE~~; Minnesota Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; Naturegate page, available ~~HERE~~; The Spruce page, available ~~HERE~~; Gail Harland, The Weeder’s Digest: Identifying and Enjoying Edible Weeds (Devon, England: Green Books, 2012), 66-67.

* For the etymology, cf., “Origin of Some Common Names of Plants compiled by Nina Curtis on behalf of The Tortoise Table,” available ~~HERE~~.

** Cf., for native status, Richard Dickinson and France Royer, Weeds of North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 543; versus the following identifying foreign origins: Native Plant Trust, available ~~HERE~~; Minnesota Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; Naturegate page, available ~~HERE~~.

†U.S. Forest Service Plant of the Week page, available ~~HERE~~.

†† Cf., Richard Dickinson and France Royer, Weeds of North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 543; Native Plant Trust, available ~~HERE~~; Minnesota Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; Naturegate page, available ~~HERE~~; The Spruce page, available ~~HERE~~; Gail Harland, The Weeder’s Digest: Identifying and Enjoying Edible Weeds (Devon, England: Green Books, 2012), 66-67.

14)

* Cf., Gerald’s Herbal, part 2, Chap. 84: Of Sorrel; Richard Dickinson and France Royer, Weeds of North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 604, 618-19; Dennis Horn, Tavia Cathcart, Thomas E. Hemmerly, and David Duhl, Wildflowers of Tennessee the Ohio Valley and the Southern Appalachians (Auburn, WA: Lone Pine Publishing, 2018), 85; “Sorrel (n.)” and “Dock (n.3),” Online Etymology Dictionary, available ~~HERE~~, and ~~HERE~~; Michael L. Charters’ extensive compilation of plant names’ histories, available ~~HERE~~; on commonly eaten sorrels, cf. Grower’s Exchange, available ~~HERE~~.

** Cf., Richard Dickinson and France Royer, Weeds of North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 618-19; Dennis Horn, Tavia Cathcart, Thomas E. Hemmerly, and David Duhl, Wildflowers of Tennessee the Ohio Valley and the Southern Appalachians (Auburn, WA: Lone Pine Publishing, 2018), 85.

*** Anne Van Arsdall, Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine, chapter five: “A New Translation of the Old English Herbarium” (New York: Routledge, 2002), 122, 154, 165, respectively.

† David E. Allen and Gabrielle Hatfield, Medicinal Plants in Folk Tradition: An Ethnobotany of Britain and Ireland (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2004), 98-99.

†† Alice Henkel, Weeds Used in Medicine, U. S. Department of Agriculture, Farmers’ Bulletin No.188 (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1917), 13-17; digitized by the Missouri Botanical Garden, available ~~HERE~~.

†††Huron H. Smith, Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians (Milwaukee, WI: Order of the Board of Trustees, Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee, 1932), 381.

# Teresa McLean, Medieval English Gardens (New York: The Viking Press, 1980), 207-08; 208, 173; 185, respectively.

## Joseph A. Cocannouer, Weeds: Guardians of the Soil (Old Greenwich, CN: The Devin-Adair Co., 1950, 1980), 76.

### Cf., Gareth Richards, Weeds: The Beauty and Uses of 50 Vagabond Plants (London: Royal Horticultural Society and Welbeck Publishing Group, 2021), 167-69; The Spruce Eats page, available ~~HERE~~; Four Season Foraging page, available ~~HERE~~.

∆ Douglas W. Tallamy, Bringing Nature Home: How you can Sustain Wildlive with Native Plants ( Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2021), 319

∆ ∆ Illinois Wildflowers pages, available ~~HERE~~, and ~~HERE~~.

∆∆ ∆ Richards, Weeds, Op. Cit., 167..

∆∆∆∆ Marsilio Ficino, “To Capture the Power of a Star,” from On Life, 3.8, pp.351-52, in The Book of Magic: From Antiquity to the Enlightenment, trans./ed. Brian Copenhaver (New York: Penguin Books, 2015), 351.

** Cf., Richard Dickinson and France Royer, Weeds of North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 618-19; Dennis Horn, Tavia Cathcart, Thomas E. Hemmerly, and David Duhl, Wildflowers of Tennessee the Ohio Valley and the Southern Appalachians (Auburn, WA: Lone Pine Publishing, 2018), 85.

*** Anne Van Arsdall, Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine, chapter five: “A New Translation of the Old English Herbarium” (New York: Routledge, 2002), 122, 154, 165, respectively.

† David E. Allen and Gabrielle Hatfield, Medicinal Plants in Folk Tradition: An Ethnobotany of Britain and Ireland (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2004), 98-99.

†† Alice Henkel, Weeds Used in Medicine, U. S. Department of Agriculture, Farmers’ Bulletin No.188 (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1917), 13-17; digitized by the Missouri Botanical Garden, available ~~HERE~~.

†††Huron H. Smith, Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians (Milwaukee, WI: Order of the Board of Trustees, Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee, 1932), 381.

# Teresa McLean, Medieval English Gardens (New York: The Viking Press, 1980), 207-08; 208, 173; 185, respectively.

## Joseph A. Cocannouer, Weeds: Guardians of the Soil (Old Greenwich, CN: The Devin-Adair Co., 1950, 1980), 76.

### Cf., Gareth Richards, Weeds: The Beauty and Uses of 50 Vagabond Plants (London: Royal Horticultural Society and Welbeck Publishing Group, 2021), 167-69; The Spruce Eats page, available ~~HERE~~; Four Season Foraging page, available ~~HERE~~.

∆ Douglas W. Tallamy, Bringing Nature Home: How you can Sustain Wildlive with Native Plants ( Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2021), 319

∆ ∆ Illinois Wildflowers pages, available ~~HERE~~, and ~~HERE~~.

∆∆ ∆ Richards, Weeds, Op. Cit., 167..

∆∆∆∆ Marsilio Ficino, “To Capture the Power of a Star,” from On Life, 3.8, pp.351-52, in The Book of Magic: From Antiquity to the Enlightenment, trans./ed. Brian Copenhaver (New York: Penguin Books, 2015), 351.

15)

speed my judgment, and did not properly, long-ly enough investigate … that massive patch of gold spread across the lawn is not creeping buttercup, but the ‘clustered,’ ‘bundled,’ ‘little frog,’ that is, precisely the species I proposed to introduce: the Early Buttercup (Ranunculus fascicularis). The suspicion should have arisen at the leaves’ lack of any pale splotches, then clinching with the plants’ lack of stolons (no matter their density therein, they are not multiplying by above or below ground runners!). There are features, however, that make sure identifications a bit challenging. So!, Early Buttercup, share a few words about yourself:

Perhaps your early appearance accounts for your variability, as you sometimes bear a single flower per stem, sometimes multiple; sometimes these flowers’ petals are longer than wide, sometimes not, and sometimes they are wider at their base, and sometimes not; your leaves are mostly basal, mostly compound, mostly lobed, but not always, and your leaf tips may be round or blunt or pointed, leaf surfaces and stems and stalks may all be silk-like hairy or smooth, or first one then the other. Those flowering stems are sometimes tinted purple, or stay pale green. For being a ‘little frog,’ you have a tendency to prefer drier conditions—hence surprising where you have clustered in my front yard (but, you are indeed barely six inches by six inches, hence your stature suggests you are not your taller cousins). The most apt test to your identification, though not foolproof, is your earliest of blooming times (and your native range is roughly the eastern half of the United States, with a little spread in south eastern Canada). For biodiversity, you are a keen attractor of bees, the honey, little carpenter, cuckoo, mason, and halictid, as well as syrphid flies; occasionally, too, attracting some butterflies and skippers; your seeds and a little foliage are munched by game birds, some snow buntings, chipmunks, squirrels, and voles.†

Perhaps your early appearance accounts for your variability, as you sometimes bear a single flower per stem, sometimes multiple; sometimes these flowers’ petals are longer than wide, sometimes not, and sometimes they are wider at their base, and sometimes not; your leaves are mostly basal, mostly compound, mostly lobed, but not always, and your leaf tips may be round or blunt or pointed, leaf surfaces and stems and stalks may all be silk-like hairy or smooth, or first one then the other. Those flowering stems are sometimes tinted purple, or stay pale green. For being a ‘little frog,’ you have a tendency to prefer drier conditions—hence surprising where you have clustered in my front yard (but, you are indeed barely six inches by six inches, hence your stature suggests you are not your taller cousins). The most apt test to your identification, though not foolproof, is your earliest of blooming times (and your native range is roughly the eastern half of the United States, with a little spread in south eastern Canada). For biodiversity, you are a keen attractor of bees, the honey, little carpenter, cuckoo, mason, and halictid, as well as syrphid flies; occasionally, too, attracting some butterflies and skippers; your seeds and a little foliage are munched by game birds, some snow buntings, chipmunks, squirrels, and voles.†