Medieval Philosophy

Buttons, below, will take you to course & reading notes on noted thinkers:

for more ... grey button at left ... my old site ... until this collection of resources is updated. |

Even further below, an introductory summary ...

MEDIEVAL PHILOSOPHY ~ PHI-3020 ~ Belmont University

“How then can we speak of the divine names?

How can we do this if the Transcendent surpasses all discourse and all knowledge,

if it abides beyond the reach of mind and of being, if it encompasses and circumscribes,

embraces and anticipates all things while itself eluding their grasp and escaping

from any perception, imagination, opinion, name, discourse, apprehension, or understanding?

How can we enter upon this undertaking if the Godhead is superior to being and is unspeakable and unnameable?”

—Pseudo-Dionysius, The Divine Names, 593A-B.

“How then can we speak of the divine names?

How can we do this if the Transcendent surpasses all discourse and all knowledge,

if it abides beyond the reach of mind and of being, if it encompasses and circumscribes,

embraces and anticipates all things while itself eluding their grasp and escaping

from any perception, imagination, opinion, name, discourse, apprehension, or understanding?

How can we enter upon this undertaking if the Godhead is superior to being and is unspeakable and unnameable?”

—Pseudo-Dionysius, The Divine Names, 593A-B.

“Oh, in the name of all your mercies, O Lord my God, tell me what you are to me!

Say into my soul: I am thy salvation. Speak so that I can hear.

See, Lord, the ears of my heart are in front of you. Do not hide your face from me.

Let me die, lest I should die indeed; only let me see your face.”

—Saint Augustine, Confessions, Bk.I, Ch.5.

From the 3rd to the 16th centuries, across continents and shifting empires,

through pagan, Christian, Jewish, and Islamic traditions, through golden ages, dark ages, new dawns,

and bleakest hours, chronicles of lives, last days, iterations of visions, treatises and dialogues, a response to a fool, pseudonymous offering, epigrammatic guides in spiritual exercise, systematic philosophies, and mystical ecstaticisms—this course will traverse these grounds to unfold an historical and thematic introduction to the philosophy of the Middle Ages developed around the preeminent medieval concern: The Quest to Know God.

This greatest challenge in philosophy demands reflection on the relation between epistemological questions & the activity of asking them; it reveals the medieval problem of knowledge to have practical ends, affective dimensions, ethical prerequisites, & linguistic-literary demands. Our theme inspires investigations of interplays between faith & reason, style & content, demands harmony between systematic theology’s proofs for God’s existence & esotericism of mystical experience, prompts explorations into & between apophatic (negative) & cataphatic (affirmative) theologies, raises paradoxes of how to speak of the inexpressible, rethink the logic of evil as privation, & explore similarities & differences of late Platonic & Aristotelian philosophy & their synthesis together with diverse occult doctrines & fueling the creation & infusing the product of the Abrahamic traditions. Each thinker is radically distinct—yet, love, loss, evil, salvation, praise, sin, proof & doubt, reason & mystery, anxiety & peace permeate every work. This period in philosophy is unlike any other.

through pagan, Christian, Jewish, and Islamic traditions, through golden ages, dark ages, new dawns,

and bleakest hours, chronicles of lives, last days, iterations of visions, treatises and dialogues, a response to a fool, pseudonymous offering, epigrammatic guides in spiritual exercise, systematic philosophies, and mystical ecstaticisms—this course will traverse these grounds to unfold an historical and thematic introduction to the philosophy of the Middle Ages developed around the preeminent medieval concern: The Quest to Know God.

This greatest challenge in philosophy demands reflection on the relation between epistemological questions & the activity of asking them; it reveals the medieval problem of knowledge to have practical ends, affective dimensions, ethical prerequisites, & linguistic-literary demands. Our theme inspires investigations of interplays between faith & reason, style & content, demands harmony between systematic theology’s proofs for God’s existence & esotericism of mystical experience, prompts explorations into & between apophatic (negative) & cataphatic (affirmative) theologies, raises paradoxes of how to speak of the inexpressible, rethink the logic of evil as privation, & explore similarities & differences of late Platonic & Aristotelian philosophy & their synthesis together with diverse occult doctrines & fueling the creation & infusing the product of the Abrahamic traditions. Each thinker is radically distinct—yet, love, loss, evil, salvation, praise, sin, proof & doubt, reason & mystery, anxiety & peace permeate every work. This period in philosophy is unlike any other.

Introductory Summary:

Medieval Philosophy profoundly challenges one’s ability to craft a simple synopsis or brief introduction. What is medieval philosophy? When is the medieval period? Some time between antiquity and modernity? Where did it take place? Intellectual centers were declining and being invented anew, some were in “pagan” lands, some in the Islamic world, and some in Jewish and Christian lands. Were these different centers all to be considered producing one medieval period?

Thus, this introduction will make gross summations and sacrifice detail to the aim of an initial characterization:

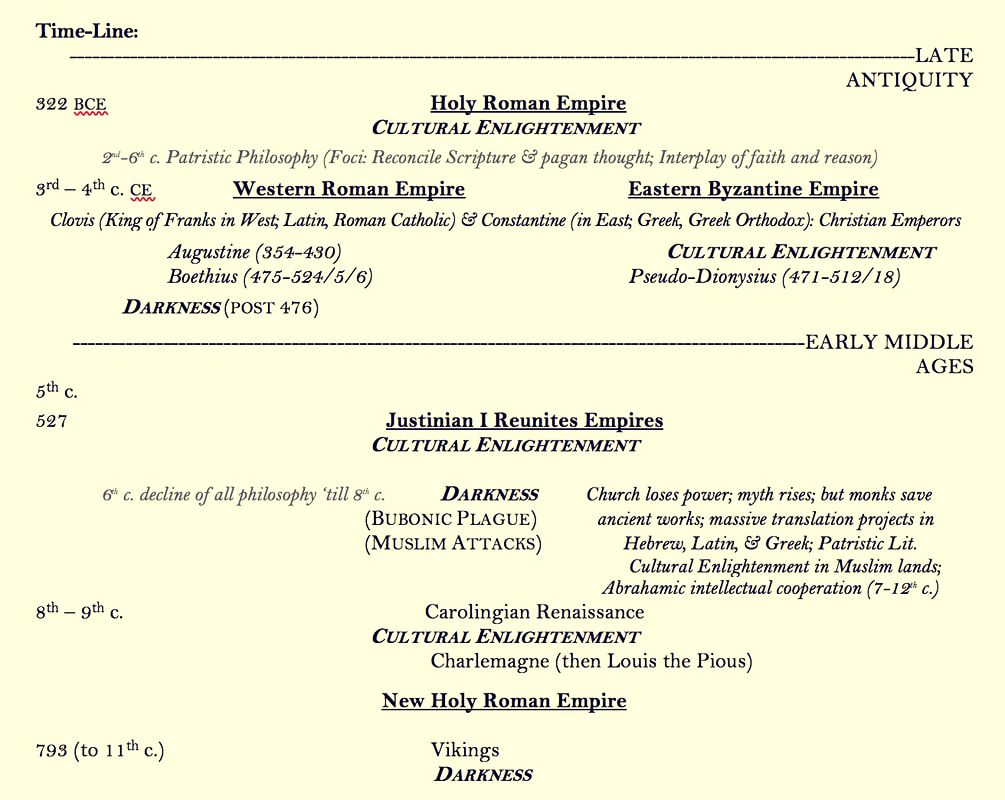

When? “Medieval” comes from the Latin medium aevum, “middle age,” thus, Medieval Philosophy will refer to the philosophic work done in the “Middle Ages,” from the end of the Roman Empire to the rise of the Renaissance, that is, roughly from the 5th to the 15th centuries (although late antique philosophy, post the death of Aristotle in 322 b.c.e., is important to its study and philosophy conducted in the medieval style persisted into the late 17th c. with some scholars including oft-considered modern philosophers, e.g. Descartes, in its reign).

What? A rough declaration about medieval philosophy can say that it was one half influenced by Plato and Platonists and the other half by Aristotle and Aristotelians. These parts were then intellectually synthesized, necessarily distorting “pure” Platonic and Aristotelian arguments, especially as they were mixed with esoteric thought (namely Hermeticism, Gnosticism, and the philosophical commentary born from the Chaldaean Oracles*) and then conforming the yield to a monotheistic conceptual framework. This foundation yielded a remarkably complex world of thought.

Medieval philosophy is primarily religious thought, but in talking about religion through this history, few topics are left unaltered. For instance, one cannot think about religion without considering cosmological and teleological questions, metaphysical and ontological questions about being and reality, human nature, and those about the self and its relation to the other, thus, ethical, social, and political questions. And, when one thinks about any of these, one cannot escape logical and epistemological questions, too.

Where? The intellectual loci of course centered on Athens, Rome, Paris, and Alexandria, but also included London, Canterbury, Oxford, Hippo, Carthage, Jerusalem, Constantinople, Chalcaedon, Naples, Ravenna, Florence, Louvain, Cologne, and many more cities. Discussing where, it is perhaps easiest to consider location as ideological regions, those lands that became Christian, Jewish, and Islamic, spreading across Europe and North Africa.

We can see already the breadth of the study we are to undertake: philosophy spanning over and beyond a whole continent, roughly ten centuries, and three monotheistic traditions and their influence by numerous veins of pagan culture, religion, and spirituality.

Perhaps the greater question as we embark on our study of Medieval Philosophy is why this vast and rich historical period in philosophy is and has been so neglected?

Thus, this introduction will make gross summations and sacrifice detail to the aim of an initial characterization:

When? “Medieval” comes from the Latin medium aevum, “middle age,” thus, Medieval Philosophy will refer to the philosophic work done in the “Middle Ages,” from the end of the Roman Empire to the rise of the Renaissance, that is, roughly from the 5th to the 15th centuries (although late antique philosophy, post the death of Aristotle in 322 b.c.e., is important to its study and philosophy conducted in the medieval style persisted into the late 17th c. with some scholars including oft-considered modern philosophers, e.g. Descartes, in its reign).

What? A rough declaration about medieval philosophy can say that it was one half influenced by Plato and Platonists and the other half by Aristotle and Aristotelians. These parts were then intellectually synthesized, necessarily distorting “pure” Platonic and Aristotelian arguments, especially as they were mixed with esoteric thought (namely Hermeticism, Gnosticism, and the philosophical commentary born from the Chaldaean Oracles*) and then conforming the yield to a monotheistic conceptual framework. This foundation yielded a remarkably complex world of thought.

- * Hermeticism is a religious-philosophical dialogic system attributed to the Egyptian Hermes Trismegistus (1600’s scholarship dates it ca. 200 b.c.e – 200 c.e) and advocates the One as ultimate source in a tripartite system and entails a mystical doctrine concerning alchemy, astrology, and theurgy. Gnosticism (gnosis, knowledge), attributed to Alexandria, Athens, Rome, and the greater Indian empires with wide affinities from Judaism to Buddhism, promises salvation through mystical knowledge via a pantheistic, idealist, and dualistic truth of divine union versus entrapment in the degradation of matter. Equally obscure are the origins of the surviving fragments of the Chaldean Oracles, the second century Hellenistic commentary on an unknown mystical poem attributed to the unknown Zoroaster.

Medieval philosophy is primarily religious thought, but in talking about religion through this history, few topics are left unaltered. For instance, one cannot think about religion without considering cosmological and teleological questions, metaphysical and ontological questions about being and reality, human nature, and those about the self and its relation to the other, thus, ethical, social, and political questions. And, when one thinks about any of these, one cannot escape logical and epistemological questions, too.

Where? The intellectual loci of course centered on Athens, Rome, Paris, and Alexandria, but also included London, Canterbury, Oxford, Hippo, Carthage, Jerusalem, Constantinople, Chalcaedon, Naples, Ravenna, Florence, Louvain, Cologne, and many more cities. Discussing where, it is perhaps easiest to consider location as ideological regions, those lands that became Christian, Jewish, and Islamic, spreading across Europe and North Africa.

We can see already the breadth of the study we are to undertake: philosophy spanning over and beyond a whole continent, roughly ten centuries, and three monotheistic traditions and their influence by numerous veins of pagan culture, religion, and spirituality.

Perhaps the greater question as we embark on our study of Medieval Philosophy is why this vast and rich historical period in philosophy is and has been so neglected?

Most philosophy programs and textbooks skip from Aristotle to Descartes, that is from 322 b.c.e. to 1596 c.e.. The presumption is often that, in between, was nothing but the “Dark Ages,” those times in which nothing of philosophic merit happened. The term “medieval” itself is a derogatory term, indicating something primitive or out of date; it was a name for the period invented in the 15th c. (1469) by the Italian humanist and pope’s librarian, Giovanni Andrea, to differentiate his modernity, with the humanists’ rebirth (renascentia) of the better, illustrious and glowing ancient Greek and Roman culture, from the “middle” or intervening “dark ages,” the gloomy years of barbarism.

From then to now, we see the continued rejection of the period and it philosophy. While the late 1800’s brought a wealth of rigorous study into medieval intellectual history and philosophy, demonstrating the richness and originality of medieval thought, many scholars and the profession of philosophy continue to routinely neglect its serious study. Some dismiss its philosophic work by saying it is nothing but theology; some say it is nothing but linguistic obsession (i.e. the Scholastics); or others say that it is wholly monotonous reinterpretations or mere misunderstandings of ancient Greek philosophy.

Our own interest will be very complex, but the opposite of ambivalent. Thematically, we are uniting our study of Medieval Philosophy around the theme The Quest to Know God. This theme will reveal the seemingly epistemological question (“knowledge of …”) to necessitate phenomenological reflection (by which I mean an embodied reflection on the cooperative creation of meaning)—in other words, any answer as to the knowledge of God demands we pay attention to the asking of the questions … to know is to quest … asking the questions will change you and you must be in a certain way so as to ask and so too to know.

Medieval Philosophy is radically exciting because, first, it takes on the hardest question, the greatest challenge, in epistemology: the knowledge of God—how can we crummy, finite mortals know the Perfection that is the Absolute?, and, second, because it reveals this epistemological question to have the farthest reaching impacts: it affects practical ends, has ethical prerequisites, lays bare the affective dimension of the exercise of reason, rattles our reliance on logic, and forces our philosophical content to pay heed to literary forms. We will see these attributes in our explanation of the quest to know God through the following thinkers:

From then to now, we see the continued rejection of the period and it philosophy. While the late 1800’s brought a wealth of rigorous study into medieval intellectual history and philosophy, demonstrating the richness and originality of medieval thought, many scholars and the profession of philosophy continue to routinely neglect its serious study. Some dismiss its philosophic work by saying it is nothing but theology; some say it is nothing but linguistic obsession (i.e. the Scholastics); or others say that it is wholly monotonous reinterpretations or mere misunderstandings of ancient Greek philosophy.

- “Today, in our highly developed societies, we take a complex and ambivalent interest in the Middle Ages, but centuries of scorn lie just below the surface. We view the Middle Ages as primitive, attractive, perhaps, like African art but definitely barbarous, a source of perverse pleasure and a way of revisiting our origins” (Jacques le Goff, The Medieval Imagination, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1988), 19).

Our own interest will be very complex, but the opposite of ambivalent. Thematically, we are uniting our study of Medieval Philosophy around the theme The Quest to Know God. This theme will reveal the seemingly epistemological question (“knowledge of …”) to necessitate phenomenological reflection (by which I mean an embodied reflection on the cooperative creation of meaning)—in other words, any answer as to the knowledge of God demands we pay attention to the asking of the questions … to know is to quest … asking the questions will change you and you must be in a certain way so as to ask and so too to know.

Medieval Philosophy is radically exciting because, first, it takes on the hardest question, the greatest challenge, in epistemology: the knowledge of God—how can we crummy, finite mortals know the Perfection that is the Absolute?, and, second, because it reveals this epistemological question to have the farthest reaching impacts: it affects practical ends, has ethical prerequisites, lays bare the affective dimension of the exercise of reason, rattles our reliance on logic, and forces our philosophical content to pay heed to literary forms. We will see these attributes in our explanation of the quest to know God through the following thinkers:

Philo “The Mystic Way,” Selections (25 BCE-50 CE, Alexandria) Descriptions; Mystical experience

Augustine’s Confessions (354-430, Hippo) Autobiography; relig.&phi. conversions; evil; memory/time

Pseudo-Dionysius’ The Divine Names (ca. 471-512/18, Syria) Pseudonymous encyclopedia names/spir.exercise

Boethius’ Consolations (475-524/5/6, Rome) Prosimetrum of dialogue/poetry when imprisoned; evil

Solomon Ibn Gabirol’s The Fountain of Life (ca. 1021-1058) Universality of substance

Anselm’s Proslogion (1033-1109, Canterbury) Ontological Proof

Al-Ghazali’s On Knowing Yourself and God [Alchemy of Happiness] (1055/8-1111, Iraq) Spiritual exercise

Yehuda (Judah) Halevi “Names God,” Kuzari (ca.1075-1141 Spain) Rabbi/Student dialogue; divine names

Rabbi Azriel of Gerona’s “Explanation of the Ten Sefirot” (ca. 1160-1238) Emanation theory

Aquinas’ Summa Theologica (1225-1274, Sicily) Systematize relig.&phi.; scholasticism; Five Ways

Teresa Avila’s The Interior Castle (1515-1582) Spiritual exercise/contemplative prayer

Augustine’s Confessions (354-430, Hippo) Autobiography; relig.&phi. conversions; evil; memory/time

Pseudo-Dionysius’ The Divine Names (ca. 471-512/18, Syria) Pseudonymous encyclopedia names/spir.exercise

Boethius’ Consolations (475-524/5/6, Rome) Prosimetrum of dialogue/poetry when imprisoned; evil

Solomon Ibn Gabirol’s The Fountain of Life (ca. 1021-1058) Universality of substance

Anselm’s Proslogion (1033-1109, Canterbury) Ontological Proof

Al-Ghazali’s On Knowing Yourself and God [Alchemy of Happiness] (1055/8-1111, Iraq) Spiritual exercise

Yehuda (Judah) Halevi “Names God,” Kuzari (ca.1075-1141 Spain) Rabbi/Student dialogue; divine names

Rabbi Azriel of Gerona’s “Explanation of the Ten Sefirot” (ca. 1160-1238) Emanation theory

Aquinas’ Summa Theologica (1225-1274, Sicily) Systematize relig.&phi.; scholasticism; Five Ways

Teresa Avila’s The Interior Castle (1515-1582) Spiritual exercise/contemplative prayer

A Brief Historical Sketch:

The Medieval period is typically divided in three parts: Early Middle Ages (476-1000, which includes Late Antiquity), High Middle Ages (1000-1300), and Late Middle Ages (ca. 1300-1453).

I) Late Antiquity (322 b.c.e.-480 c.e.) and the Early Middle Ages (476-1000):

The Roman Empire: The Hellenistic Period:

Roughly between Aristotle (post-322 b.c.e) and Boethius (pre-480 c.e.).

Around the 1st c. b.c.e., the Roman Empire technically came to be an empire in the sense of being ruled by emperors, although the growth of the Roman Republic had been happening since the 6th c. b.c.e., most notably when and due to the 4th c. b.c.e.’s Alexander the Great (ca. 356-323 b.c.e.) leading the Greek armies against the Persian Empire and established Greek Kingdoms throughout Egypt, Palestine, Syria, and Asia Minor. The Greeks called themselves “Hellenes,” thus the name we call the period by: the Hellenistic. This period was Greek, but distinct from Classical Greek culture; Greek was a second language for most new-Hellenes, and Alexandria became a new locus of Greek education and culture, especially for science, mathematics, medicine, and philosophy, while Athens remained an educational and cultural center for philosophy and rhetoric. During this time, educated Romans knew Greek and exerted much energy (especially Cicero, Lucretius, and Seneca) translating and commenting on Greek philosophy in Latin, while many other thinkers simply wrote still in Greek (e.g., Epictetus, Plutarch, Marcus Aurelius, and Plotinus). The turbulent transition from the prior to common era saw Julius Caesar fall, the rise of Mark Antony and Octavian, the latter defeating the former and Cleopatra, and hence becoming Augustus and ensuring more political stability and flourishing through many successions (for the most part, some bumps, e.g., Nero, some heights, e.g., Hadrian, Marcus Aurelius) to Commodus around 180 c.e.,, which many mark as its height and beginning of the decline.

The Two “Roman Empires:”

The empire was too large to be singularly controlled, extending as it did from England to North Africa to Syria, its eastern half speaking Greek, its western half speaking Latin. Many regions were invaded or infiltrated by outsiders, the “barbarians” of the Goths, Vandals, Huns, Franks, etc. The Emperor Diocletian divided the empire in 286 c.e. into two halves: the Eastern and Western [some histories attribute the split to Constantine and others to the death of Emperor Theodosius I in 395], thus, the middle ages had two “Roman Empires” beginning from the 3rd c., the Eastern one in Constantinople (Greek Orthodox) and another in the West declared by Rome and eventually housed in Germany (Latin Catholic).

The Eastern Roman Empire: The Byzantine Empire:

The Byzantine Empire was founded in Late Antiquity by Constantine, who became emperor in 324 c.e., and was the first Christian emperor. In 330, he moved the capital of the Roman Empire from Nicomedia to Byzantium, and it became called New Rome or Constantinople (this new empire is distinguished from the Ancient Roman Empire in several ways, from language to religion to culture). Emperor Heraclius formalized the division of the empires by reforming its administration, army, and declaring Greek the official language. The Eastern, Byzantium empire lasted until about 1453, and was powerful economically, culturally, and militarily, despite several periods of suffering, notably by Turkish invasions (ca. 1071) and the Fourth Crusade (1204), which left it dissolved into different Greek and Latin regions or states, and numerous civil wars (14th c.), which eventually led to the Fall of Constantinople and the conquest of remaining territories by the Ottoman Empire (15th c.).

The Western Roman Empire:

The Western Roman empire existed intermittently between the 3rd and 5th c.. In 410 c.e. came the first major and successful attack on Rome by the Visigoths; they starved Rome for two years before being invited in, the starving citizens preferring servitude to continued starvation. They raided and plundered the city, but found no food, thus after making the streets run in blood and architectural wonders go up in flame, most of the Goths moved on to other cities, eventually settling in Gaul. Following, were numerous invasion by outsiders, including the Vandals and Huns. The Western Roman Empire ended officially in 476 c.e., when the Goths deposed Romulus Augustulus, the last de facto Western Roman emperor [this date is sometimes offered as the end of the Roman empire and the birth of the Middle Ages proper]. After this time, the former empire’s grandeur disintegrated into lawlessness, in “darkness.” Over the next centuries, populations decreased all over, illiteracy spread, as did disease and poverty. The architectural wonders fell into ruins, people scavenged them for building materials. The world was in a disintegration. The very slow ignition of unity came not from a new emperor, but from missionaries and monks with the spread of Christianity. [The Western Roman Empire was reputedly re-founded as the Holy Roman Empire, although the latter was German and contained little of the same territory.]

Rise of Christianity and the Re-Conquest by the Eastern Empire of the Western:

This period is remarkable for its rise and spread of Christianity. In the Western part of the empire, amidst harsh living conditions and no sense of security, Christianity proved the only thread of unity amongst people otherwise divided and quickly combative. It also promised people who lived in constant wariness a hope of everlasting peace.

Constantine, in the East, converted to Christianity, which led many to follow suit. Including Clovis (d.511), in the West, the Barbarian King of the Franks, who converted and used Christianity as a way of converting the people whose territories he took over (then called the Merovingian Dynasty). Christianity also provided him an excuse for his constant invasion: holy war.

In 533 c.e., from Constantinople [Eastern/Byzantine Empire], Roman armies led by Emperor Justinian I (483-565, ruled 527-565) pushed west to reclaim their former lands. The Byzantium warriors from Constantinople surge west to Rome, reconquering lands, leaving immense bloodshed in its wake. His reign saw the rewriting of Roman law, a revival of Byzantine culture, and much building, including the greatest cathedral in Constantinople. He was largely, albeit temporarily successful in his reunion of the Empire. By 542 c.e., his armies had reclaimed most of the Mediterranean, however, at the same time came the bubonic plague. The disease was fierce and deadly. The plague infected one half of the population of Constantinople (it is approximated that 100 million were killed), including the emperor (but, he survived, no matter how scarred both physically and mentally, the disease making him even more ruthless). Following the plague came starvation and a general halting of all work and everyday activity. In 542 the plague mostly died (future centuries had further bouts), but it took centuries to rebuild and repopulate. With the death of Justinian I, the empire could not continue to sustain the lands they had recaptured. The troops began to withdraw, bringing back a deeper darkness to start the 7th c.

Trade ceased, architectural innovation ceased, education was nil, the populations were sparse, culture was sparser. Myth and superstition took over. The Catholic Church condemned these stories, but the villagers paid little heed. Most of life was misery; half of all children died; most children who lived lost at least one parent before they became adults. The only unity at this time was found in the Church; the Churches were the only centers of commerce, light, and diversion.

Without the monks, we would have had almost no ancient works preserved. There was no real education or literacy outside of the clergy and books were being burned constantly when labeled as heretical. Jews in Alexandria were translating the Jewish Scriptures into Greek, and the New Testament was written in Greek, as well. Thus, Christianity spread first through the Greek-speaking residents, then later through the Latin speakers. Its literature (what Christians call the Old and New Testaments, and other religious writing from the 1st to 6th c., called “Patristic” literature, that is, “of the Fathers [patres] of the Church”) accounts for most of the volume of work of this period. Some of the most notable patristic thinkers included (Greek writers) Athanasius, Chrysostom, Gregory Nazianzen, Gregory of Nyssa, Origen, (Latin writers) Ambrose, Augustine, Jerome, and Gregory the Great.

Central patristic debates: Trinitarian and Christological controversies. Whether Jesus was both God and man, whether he had two natures and their relation, if so, and whether he had a human soul? How the divinity of Christ and the Holy Spirit can be reconciled with the doctrine that God is One?

These debates led to several ecumenical councils at Nicaea, Constantinople, Ephesus, and Chalcedon. Those accepting their decisions were named orthodox (“right-teaching”) or Catholic (“found everywhere”), while those who did not were named heretics (variously, Arians (the Goths), Nestorians, etc.).

Islam and Muslim Attacks in the 7th c. and the rise of the Carolingian Dynasty:

Followers of the prophet Mohammed (d. 632 c.e.) began attacking the Roman empire from the 7th c. onwards. Islam became the dominant religion (and Arabic the dominant language) in the Middle East, North Africa, and some of Spain, although these lands still were home to Jews and Christians, both heretics and orthodox, and their knowledge of Greek, especially Greek medicine, permitted their favor and survival. This was the period of the Islamic Golden Age and saw the massive advance of science and philosophy. Massive translation projects were undertaken around the 9th c. of Greek medical, scientific, and philosophical texts into Arabic (sometimes also Syriac), as well as Persian and Indian writings. In the 12th c., Spain became a center of translation of these texts, as well as Arabic originals, into Latin, often by Jews who knew both Arabic and Latin.

In 732 there was the massive battle between the Christian Franks and the Muslim Moors. The Moors, rightly, saw that Europe was too busy fighting amongst itself. They entered and tore through France, causing widespread casualties. They turned northward and met the Frankish general Charles “the Hammer” Martel, who had seen the threat coming and enlisted a professional army, funded by the Church (rather unwillingly on their part). Charles Martel was an early member of the Carolings, a Frankish noble family, whose power was consolidated in the late 7th c. (known as the Carolingian Dynasty, which usurped power from the Merovingian Dynasty, the former rulers of the Franks, in 751 with papal consent). Charles Martel defeated the Moors. The general was noted as the defender of Christendom, making this victory into an eventual Christian empire, his grandson being Charlemagne, King of the Franks, the first official Emperor in nearly three centuries.

Carolingian Renaissance and the rise of Charlemagne: (late 8th – 9th c.):

The Carolingian Renaissance is one of three commonly designated medieval renaissances. It was a period of intellectual and cultural revival centering in the reigns of the Carolingian rulers, Charlemagne and Louis the Pious. The period hearkened the original Roman Empire of the 4th c. and saw an increase in educational and cultural practices, from writing to the arts, architecture to religious study and reform.

Charlemagne rose to power strongly, viciously and with ruthless religious fervor, beheading all those who failed to convert or were caught worshiping other gods. He never lost a military conquest, rebirthed education, stabilized and rebirthed the financial importance of Europe in the world, and reawakened culture, his empire spreading (at its largest around 800 c.e.) from France to Switzerland to Poland and to most of Italy. This new Holy Roman Empire is as large as the first Roman Empire, albeit not the same exact territory as the original, but it is beginning from near ruin: its infrastructure is mostly rotted and destroyed, its people mostly ignorant. He tires his best to pull Europe from the darkness.

Establishment of the Schools and Intellectual Growth: While Charlemagne himself was illiterate, although took great effort to learn to read and write, he founded numerous schools for children of all ages and classes throughout the empire to increase literacy and address the increasing problem of the court not having anyone who could be scribes and parishes that had no one who could read the Bible and more and more regions developing dialectics unintelligible to the rest of the empire. With the establishment of schools, Charlemagne called leading scholars to his court. This period also saw the invention, by Alcuin of York, of the Trivium and Quadrivium, the form and ordering of subjects of study. Another invention was the Carolingian Minuscule, a script, called a “book-hand,” that introduced clear uppercase letters, invented lower case letters, added spaces between words, and standardized overall the Roman alphabet. This initiated the mass translation of philosophic works into Latin.

Charlemagne ruled for over three decades before being coroneted as Emperor, as which he ruled for over 14 years. In this time, 793 c.e., he faced a vicious onslaught of heathens from the north: The Vikings. They came in and sacked every Church and monastery they found, finding enormous wealth and no fighting back. They quickly moved further and further south, eventually setting its sight at the heart of the empire. The empire paid bribes to the Vikings to keep them back; this impoverished the empire and fostered the Vikings. They vicious raids pushed back much of the advancement that Charlemagne’s reign had produced. The Carolingian Dynasty saw its decline.

The Vikings plundered and ruled for a quarter of a century, until King Alfred the Great (d.899), in the south of England, eventually defeated them in the British Isles. The Vikings persisted throughout the world for another half century or so.

By the middle of the 11th century:

… 600 years of misfortune had faced the Europeans of the middle ages. The Viking threat faded, but a new threat rose from within: the medieval knights themselves. With the end of the Viking invasions, there were a surplus of Knights who had nothing to do. They allied with local lords and became their thugs; they then attacked the local peasants regularly, terrorizing them, taking from them what they needed. The Catholic Church, which spent this century undergoing immense monastic reform, namely in the advancement of general virtuosity, which also inspired secular reform and the advancement of morality, thus, the Church tried hard to control the knights and ease the violence. Often doing this by bringing the knights together at night in open fields lit by fires before large piles of all the relics of the Saints; they commanded the knights to obey them and cease their violence or else the Saints would haunt them. The Church issued two dictates on their stance on war; the Peace of God and the Truce of God (do not fight against those who cannot defend themselves and there should be truce times at night and holidays).

Medieval Armored Knight and Horse, The Met, NYC.

Medieval Armored Knight and Horse, The Met, NYC.

II) The High Middle Ages (1000-1300):

The Crusades:

A better way, though, to busy the knights was to give them a new cause: a Crusade. The first Crusade was ordered by Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont in 1095. The Crusades began with a vengeance—they were holy wars declared to reclaim Jesus’ home that had been “defiled by heathens” (i.e., called for the liberation of Jerusalem from Muslim control). Tens of thousands of soldiers were mobilized; Jerusalem was recaptured in 1099, as were other regions. 200 years saw nine crusades and the deaths of millions. By the end of the Middle Ages, all Islamic territories in what is today Spain, Portugal, and Southern Italy were captured and Christianized. While the bloodshed was immense, the push to Jerusalem and beyond resulted in the crusaders bringing back the plunder of knowledge. Over the next couple centuries, it spawned a rebirth of trade and architecture (roads and walls and houses, as well as cathedrals and educational centers). Military supply lines led to building of roads and supply of other commodities and encouragement of travel. Populations started to increase. Nevertheless, as the Crusades proceeded, so did the decline of the Byzantine Empire.

Thus, the High Middle Ages see Europe’s overall revival in urbanization, military expansion, and intellectual pursuits. Infrastructure projects saw roads and rivers connecting growing urban centers and trade began to flourish once more. Political power was consolidated under kings (mainly in France, England, and Spain), instead of papal authority (although, most of the empire was considered to be under Christian authority), while new kingdoms in Central Europe, newly converted to Christianity, began to flourish (until the 16th c. brought invasions of the Ottoman Empire).

There were numerous religious movements in the High Middle Ages. The general increase in wealth and security in the lands led to the endowment of land and building of parishes for the Church, which, in turn, increased its influence on the peasants. But, this time also saw a strong increase in what it deemed heretical notions of religion.

III) The Late Middle Ages (ca. 1300-1453):

From the comparatively flush good times of the High Middle Ages, the Late Middle Ages began with crisis. The first factor was the Great Famine (1315-17), the next was the Black Death, which killed a third of the population by the mid-14th c. The increased populations and urbanization from the High Middle Ages permitted the effects of famine and disease to spread rapidly and be felt intensely. The new and sharp decrease of populations led to shortages of workers and popular uprisings. The Church also suffered strongly from internal rifts. Nevertheless, amongst the calamities of these times, innovation and intellectual life continued to be strong.

There was a strong rise of nation-states in this period, especially the Kingdoms of England and France (and others along the Iberian Peninsula), precipitated by the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453) between those two kingdoms, mainly over claims by the English kings to the French throne. The war led to the decline of the fortunes of both kingdoms, although increased nationalism in each.

The Church suffered from great disarray in the 14th c.:

- The Avignon Papacy was one initiating disaster: a deadlocked conclave elected Clement V as pope; he was a Frenchman and decided to keep his papal enclave in France, in Avignon, instead of moving to Rome. This was a deep offense to Rome, and persisted 67 years, which the Romans called the “Babylonian Captivity of the Papacy.” Seven popes stayed in Avignon, all of them French, each increasingly under control by the French crown. It was not until 1377 the Gregory XI moved his court to Rome that this period ended.

- Western Schism: The Avignon Papacy led to the build up of the Western Schism (1378-1417). This schism led to the birth of a second line of popes (now considered illegitimate)—that is, two different men deemed themselves to be pope. Gregory XI died, which ignited the Romans to riot to insist on the election of a Roman pope; the cardinals elected Pope Urban VI in 1378, but he turned out to be a fierce and suspicious man with a violent temper; the cardinals fled to Anagni and elected Robert of Geneva (cum Pope Clement VII) as a rival pope (antipope), who then reestablished court in Avignon. The schism was ended by the Council of Constance in 1414-18. This religious turmoil quickly became a political, diplomatic crisis, splitting the Continent. The Schism continued until after the deaths of both the popes. Force and diplomacy failed to solve the problem; eventually, a Church Council was called in Pisa in 1409. This council only succeeded in making matters worse: they elected a third pope, Alexander V, who ruled for a year before dying, upon which, John XXIII took his position. The Church now had three popes. Finally, the Council of Constance met in 1414 and secured the resignations of John XXIII and the Roman successor, now Pope Gregory XII, and excommunicated the Avignon Pope Benedict XIII, who refused to resign. The council then elected Pope Martin V. Rival factions persisted and a few more antipopes were elected, but the schism was mostly over. (Although it took until well into the 19th c. for the history to be cleared up as to who was real, who was anti-, etc., with some records remaining blurry until the 20th c.)

- Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation: The turmoil gave the widespread impression of its clear corruption. While disdain had been building for a while, the turmoil prevented the complete silencing of dissidents; taking advantage of this, Martin Luther (1483-1546) published his objections against the Church, Ninety-Five Theses (mainly against the Catholic practice of Indulgences, payments for holy favor), in 1517. They were translated from Latin into German in 1518, printed, and widely copied and read (first protest aided by the printing press). Students flocked to Wittenberg to hear him lecture. He refused to retract his statements, demanded by Pope Leo X in 1520 and by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V at the Diet of Worms in 1521, and was excommunicated by the former and condemned as an outlaw by the latter. The Lutherans split from the Church in 1517 (organized by Luther et al in 1526-9), launching the further division of Catholicism from Lutheranism, Calvinism, and Anabaptism.

15th Century:

By its end, the Ottoman Empire advanced throughout Eastern Europe and conquered the Byzantine Empire and Slavic states. The key battle ground was Hungary, the edge of the Christian world. John Hunyadi, a great military figure, was named its regent-governor, and he succeeded in several massive victories against the Ottomans (these battles were cast as holy wars, Christians versus the Muslims). His son, Matthias, succeeded him as the King of Hungary and continued the campaigns against the Ottomans with papal support, eventually building the largest army of its time (called the Black Army of Hungary, mainly composed of mercenary soldiers), and repelling and stopping all attacks. Literati, artists, and scientists flocked to Hungary (the second site after Italy of the Renaissance), and the largest library of the age, the Bibliotheca Corviniana, was built. After Matthias died, the army disbanded and the Kingdom was left defenseless. They resisted the Ottoman resurgence of attacks until 1526, but then caved before the Ottoman power and the West’s general turmoil and weakening of its support by the Church due to the Protestant split. The fall to the Ottoman Empire generally signals the end of the Medieval period.

Illumination: Two Philosophers Discuss Idols

Illumination: Two Philosophers Discuss Idols

“Most disputes between people” arise because “they see some part and suppose that they have seen it all.”

--Al-Ghazzali, On Knowing Yourself and God, a translation of his Alchemy of Happiness, from the Persian, by Muhammad Nur Abdus Salam (Chicago: Great Books of the Islamic World, KAZI Publications, Inc., 2002), 53.

A Brief Philosophic Sketch:

I) Late Antique to Early Middle Ages:

The Patristic Philosophers (2nd c. ff.):

Early monotheistic philosophers were the religious minority surrounded by vast dispersions of pagan philosophers; early Christian philosophers were an even more minoritarian minority. Their New Testament doctrines were unexplained, their theological concepts were undeveloped, and their responses were unformed against pagan arguments. There was much work to be done.

Most early patristic philosophy consisted in defenses of its religious principles. Aristotelian, Stoic, Materialist, and diverse esoteric doctrines can be found within this work, but it is for the most part Platonic (of course, as defined by Neoplatonism, not by Plato’s writings themselves).

The first real schism in late antique/early patristic philosophers was about the relation of Scripture and Greek (i.e. pagan) philosophy. The divide, specifically, was between those (eventually, mainly Protestant) who argued that the New Testament utilized Greek philosophy and those (eventually, mainly Catholic) who eschewed any Greek philosophical influence on religious Scripture.

The second real schism between these philosophers concerned their answers to the interplay between faith and reason. Both groups held the religious teachings to be supreme, but one argued that reason (i.e., philosophy) positively supplemented or helped elucidate faith, whereas the other argued that reason (i.e., philosophy) had no part to play in matters of faith whatsoever, and when it intervened, this was often the source of heresies.

The 4th c. brought positive news to Christian philosophy with the conversion of Constantine and his command of the Empire being the official religion, which initiated the concretization of the political ordering of the Church. The Council of Nicea was called in 325, at which the Church concretized its views on the conception of the Trinity. This legitimacy and clarification of Church position aided the philosophical undertaking.

The Greek Philosophers of the 4th c. include: Eusebius, Gregory of Nazianz, Basil the Great, Nemesius, and, most importantly, Gregory of Nyssa—who undertook the first rational argumentation for all the teachings of the Church (including its mysteries), a pursuit continued by Anselm; Gregory’s Platonism made him emphasize the purification of the human soul and humanity’s return to God, which deeply influenced the mystical philosophies in John Scotus Eriugena and Bernard of Clairvaux. The Latin philosophers of the 4th c. include: Marius Victorinus, Ambrose, and Augustine—see below for detail on the last.

Into the 5th c., the most notable Greek-inspired Christian philosopher is Pseudo-Dionysius (see below for detail on him). P-D’s work influenced many following medieval thinkers, notably Eriugena, Hugh of St. Victor, Robert Grosseteste, Albertus Magnus, Bonaventure, and Aquinas, who all commented on P-D’s writings and ideas. The 6th c. saw a great decline in learning and philosophy until Charlemagne and the Carolingian Renaissance in the 8th c.

The Patristic Philosophers (2nd c. ff.):

Early monotheistic philosophers were the religious minority surrounded by vast dispersions of pagan philosophers; early Christian philosophers were an even more minoritarian minority. Their New Testament doctrines were unexplained, their theological concepts were undeveloped, and their responses were unformed against pagan arguments. There was much work to be done.

Most early patristic philosophy consisted in defenses of its religious principles. Aristotelian, Stoic, Materialist, and diverse esoteric doctrines can be found within this work, but it is for the most part Platonic (of course, as defined by Neoplatonism, not by Plato’s writings themselves).

The first real schism in late antique/early patristic philosophers was about the relation of Scripture and Greek (i.e. pagan) philosophy. The divide, specifically, was between those (eventually, mainly Protestant) who argued that the New Testament utilized Greek philosophy and those (eventually, mainly Catholic) who eschewed any Greek philosophical influence on religious Scripture.

The second real schism between these philosophers concerned their answers to the interplay between faith and reason. Both groups held the religious teachings to be supreme, but one argued that reason (i.e., philosophy) positively supplemented or helped elucidate faith, whereas the other argued that reason (i.e., philosophy) had no part to play in matters of faith whatsoever, and when it intervened, this was often the source of heresies.

The 4th c. brought positive news to Christian philosophy with the conversion of Constantine and his command of the Empire being the official religion, which initiated the concretization of the political ordering of the Church. The Council of Nicea was called in 325, at which the Church concretized its views on the conception of the Trinity. This legitimacy and clarification of Church position aided the philosophical undertaking.

The Greek Philosophers of the 4th c. include: Eusebius, Gregory of Nazianz, Basil the Great, Nemesius, and, most importantly, Gregory of Nyssa—who undertook the first rational argumentation for all the teachings of the Church (including its mysteries), a pursuit continued by Anselm; Gregory’s Platonism made him emphasize the purification of the human soul and humanity’s return to God, which deeply influenced the mystical philosophies in John Scotus Eriugena and Bernard of Clairvaux. The Latin philosophers of the 4th c. include: Marius Victorinus, Ambrose, and Augustine—see below for detail on the last.

Into the 5th c., the most notable Greek-inspired Christian philosopher is Pseudo-Dionysius (see below for detail on him). P-D’s work influenced many following medieval thinkers, notably Eriugena, Hugh of St. Victor, Robert Grosseteste, Albertus Magnus, Bonaventure, and Aquinas, who all commented on P-D’s writings and ideas. The 6th c. saw a great decline in learning and philosophy until Charlemagne and the Carolingian Renaissance in the 8th c.

- Augustine (354-430 c.e.):

- Saint Augustine of Hippo’s life is itself a work of art, recorded in critical detail by his own hand in his Confessions: his autobiographical exploration of his anxiety-ridden conversions (broadly including the conversion from infancy to adulthood, educationally from a reluctant student to a scholar, intellectually to philosophy and theology, and spiritually and religiously he converts from skepticism to Manichaeism and to Christianity). His biography accounts for some of his intellectual influence: his Greek and Roman education, his Manichaeism, his exposure to skepticism and Neoplatonism, and his Christian exposure and study. More specifically, we can argue that Augustine was firmly intellectually formed by the conjunction of Neoplatonism (through Plotinus, likely through Porphyry and Victorinus), with rhetoric (through Virgil and Cicero), with Christian thought (through his mother, Saint Ambrose, and the Scriptures), to which we can conclude that he as much embodies the merger of pagan Neoplatonism with Christian thought.

- St. Aquinas wrote of him: “Whenever Augustine, who was saturated with the teachings of the Platonists, found in their writings anything consistent with the faith, he adopted it; and whatever he found contrary to the faith, he amended.” These Platonic currents in his thought can be seen throughout his works. Notable examples in his work On Free Choice of the Will include the stylistic form of the work as a dialogue and his methodological and pedagogical relation he demonstrates to his student Evodius. Further, in its content, the Greek influence can be seen in his relation of faith and reason wherein the former is required as a foundation but the latter is of the utmost importance. Augustine, like Plato, privileged non-dogmatic reason; Plato and Augustine both held that the highest truth was a grasp on the form of the good, only diverging insofar as Augustine’s interpretation of the good is either God. While the forms, as either the Good itself or God, may be universal, knowable truths, this does not mean we have perfect knowledge of them.

- Boethius (ca. 475-524/5/6):

- Roman born, into important family which included emperors and counsels; thought to have been born into a Christian family, with some scholarly debate on his religiosity and whether he abandoned it for paganism; he was well educated and fluent in Greek; his education led to his hire by King Theodoric the Great, he became a senator by 25 and counsel to the kingdom of the Ostrogoths, then, in 522, appointed magister officiorum, the head of government and court services; one of his notable works was towards trying to reestablish relations between the Churches in Rome and Constantinople, this may have led to his disfavor; in 522, imprisoned and later executed by Theodoric for suspicion of conspiring with the Eastern Empire for his defense of another ex-counsel; while imprisoned, he wrote his famous Consolation of Philosophy; his whole oeuvre was concerned with the preservation of ancient wisdom, especially philosophy; he had intended to translate all of Aristotle and Plato into Latin, but completed only some (but his translation of Aristotle’s works on logic were the only significant pieces of Aristotle available in Europe until the 12th c.); many of his own commentaries were lost, but, in addition to Consolations, his works on Music, the Trinity, and Theological Tractates, and Institution Arithmetica survive.

- Pseudo-Dionysius (ca. 471-512/518):

- We do not know his real name, this Christian faithful one, the Pseudo-Dionysius, who wrote about the power of names. We believe that this Neo-Platonist believer wrote from Syria sometime between 471-512/518 C.E. He adopted the name of Dion (the) Areopagite in place of his own; Dion, or Dionysius was the distinguished convert of St. Paul from the Acts 22:17 ff. Perhaps the nameless one wants us to know nothing else about him that any truthful biography could offer. Instead of his birth date and parent’s names, we read his history through his philosophy; through the pseudonym we will deduce a biography where fragments and negations are more truthful than a narrative could ever be.

- Pseudo-Dionysius wrote a number of works including Letters, which are predominately exegeses of his thought and moral advice and four surviving treatises: The Celestial Hierarchy, which delineates the ranks of angels, the Ecclesiastical Hierarchy, which delineates the ranks of religious figures. The Divine Names, which undertakes a study of the intelligible names applied to God (i.e., Goodness, Wisdom, Yearning). The Mystical Theology, which philosophical promotes one to abandon the sensible and intelligible in order to experience a union with God. Then there are the two questioned treatises, the Theological Representations (Outlines of Divinity), which was said to be on the trinity and incarnation, and the Symbolic Theology, which reputedly analyzed the sensible names representing God (i.e. Rock, Right Hand).

- Pseudo-Dionysius’ work had a great influence, even when his identity and authority began to be questioned and challenged and even after he was declared blasphemous. I consider the most impressive of his works to be The Divine Names in which he radicalizes a method to balance denial and affirmation of our knowledge of God in reaction to our tenuous claims to knowing God. How can we know what exceeds all that we can conceive? Surely, we can know His emanations, what proceeds from Him, and therefore we can talk about these things, His creations, in order to talk about Him as their creator, but, these things are not properly God and our knowledge of them cannot apply to Him properly. Thus, every name of God we affirm, we must also negate. This means that we must stutter the names of God: He is Good and He is not Good.

8th – 9th Centuries:

The Carolingian Renaissance (late 8th – 9th c.): was a period of intellectual and cultural revival centering in the reigns of the Carolingian rulers, Charlemagne and Louis the Pious. The period hearkened the original Roman Empire of the 4th c. and saw an increase in educational and cultural practices, from writing to the arts, architecture to religious study and reform. Charlemagne founded numerous schools throughout the empire and called leading scholars to his court. Intellectual concerns included the controversy of universal concepts and growing use of dialectic. The most (and arguably the only) notable thinker of the period was John Scotus Eriugena (ca. 810-877), who systematically fused Christian and Neoplatonic thought.

II) The High Middle Ages (1000-1300):

The 11th c. saw the rebirth of philosophic work, first with Anselm of Canterbury (see below for detail on him), who defended a Neoplatonic system of philosophy, following Augustine’s lead. Following Anselm, the 11th and 12th c. philosophers became increasingly concerned with the problem of universals—that is, mereological questions of the one and the many and whether genera and species exist only in the mind or in reality, and, if in reality, whether they exist in substances or separate from them. These dialectical investigations were logical exercises that held tremendous philosophic weight for answering broader questions about religious philosophical concerns. Two notable 12th c. thinkers in these areas were Peter Abelard and his student, who took an opposing position, John of Salisbury. This century also saw the rise of a new Platonic influence centered in the school of Chartres, notable for its humanistic studies and interest in science and natural philosophy. In addition to Plato and Boethius, Chartres abounded with the writings of Hippocrates, Galen, and Islamic thought, which had preserved Aristotle throughout the early medieval turmoil. Notable thinkers there included Adelard of Bath, Thierry of Chartres, Clarenbaud of Arras, William of Conches, Gilbert de la Porrée, John of Salisbury, and Alan of Lille. The final important movement in 12th c. medieval philosophy is the mystical movement, notably Bernard of Clairvaux and students at the school of St. Victor, who sought to fuse dialectical and mystical teachings. A thinker who blurs these boundaries is Moses Maimonides.

11th century:

12th Century:

(Founding Schools of Chartres, St. Victor)

13th Century: (syntheses)

- St. Anselm (1033-1109):

- Anselm was enthroned as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1093, approximately fifteen years after writing his most famous work the Proslogion, which contains his ontological proof for the existence of God. The Proslogion seeks a single line of argumentation that will first prove (1) that God exists, (2) will then prove that all other things depend upon Him, and finally (3) prove that all the things that we have been told to think about God’s attributes by the religious tradition make sense in regard to Him. In this way faith may gain understanding through the use of reason to support what we are taught by faith. The essence of his ontological proof is that everyone can understand the statement “something-than-which-nothing-greater-can-be-thought,” this is the definition he gives for God, and in understanding it we must believe it to be true, thus believing in his existence.

- Al-Ghazali (1055/8-1111):

- A Persian Muslim mystic philosopher and theologian, he was born into a Sufi family (and eventually died) in Tus, a province in Persia (now Iran) and studied Islamic jurisprudence; he became a chief prosecutor in Baghdad in 1091 and widely lectured to massive audiences. He left his career in 1095 for a spiritual crisis; he made arrangements for his family, then gave away all his wealth and took on the life of a poor Sufi; he travelled widely, then resettled in seclusion in Tus. While a mystic, he strongly refuted Islamic Neoplatonism (c.f., Incoherence of the Philosophers), which borrowed its foundation from Hellenistic philosophy (this was a sharp critique of earlier notable Islamic philosophers Avicenna and Al-Farabi; following his text, Averroes wrote a long rebuttal of Ghazali’s work, howevr it had already made its mark on Islamic philosophy); he brought together orthodox Islam (and Shariah law) and Sufism. He is responsible for developing a systematic view of Sufism and integrating it into mainstream Islam. He left behind over 70 books on Islamic sciences, philosophy, and Sufism (in Arabic and Persian). His work was closely read by Western philosophers, including Aquinas.

- Hildegard of Bingen (ca. 1098-1179):

- German Christian mystic, Benedictine abbess; wrote numerous theological texts, liturgical songs and drama, botanical and medical texts, letters and poems, illuminations. She was offered as a tithe to the Church as a child (sometime between eight and 14 years old), suffered from visions since early youth (she wrote from the age of three), learned to read and write as a child and play music (between 70-80 compositions survive); was elected magistra and Prioress, she founded two convents, one in Rupertsberg and another in Eibingen; at the age of 42, she had a vision wherein God told her to write down her visions, which led to her penning her Scivias (“Know the Ways,” completed in 1151), she received Papal approval (Pope Eugenius III) to document her visions, which led to their credit and quick consumption by readers. She also invented her own alternative alphabet, which she called her Lingua Ignota, and also coined many original and conflated and abridged words. She left behind nine books and over 100 letters and 70 poems.

12th Century:

(Founding Schools of Chartres, St. Victor)

- Maimonides (1138-1204)

- Born in Cordoba, the son of a religious judge; schooled in law and medicine. He and his family were driven from Cordoba when he was 13 by the fundamentalist Almohads; they moved to Fez, Acre, then finally settled in Cairo. Maimonides served as the president of the Jewish community there for five years, and then served as the court physician to the vizier of Saladin in 1185. During his life, he was highly regarded for his rabbinic studies and his definitive list of the divine commandments (instead of ten, he counted 613). But, we remember him for the work we are reading selections from, The Guide for the Perplexed.

13th Century: (syntheses)

- St. Bonaventure (1221-1274):

- Doctor of the Church, Cardinal-Bishop of Albano, and Minister General of the Friars Minor; he entered the Order of the Friars Minor in 1238 or 1243 and then was sent to the University of Paris for his education under Alexander of Hales (founder of the Franciscan School); he received his “licentiate” to permit him to teach, which he did until a crackdown on the Friars, which barred them from teaching around 1256; he was readmitted eventually and awarded, along with Aquinas, the degree of Doctor in 1257. In addition to the exclusively recognized life of St. Francis, some of his writings are mystical, concerning the perfection of the soul by discharging vice and ecstatic prayer. His other writings are, variously, ascetic, dialogues on spiritual questions, meditations on the life of Christ, a work on the passion, and a treatise on the virtues.

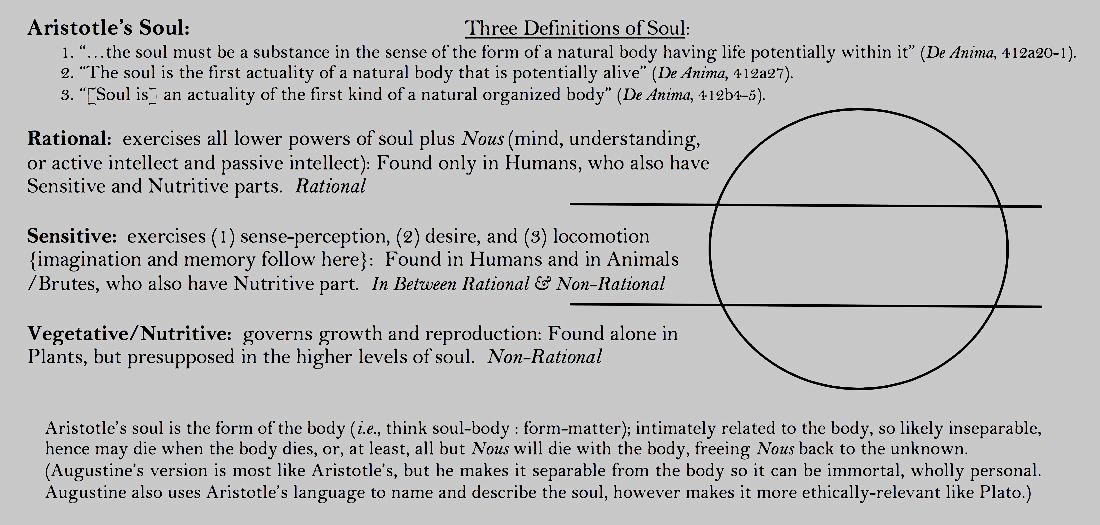

- St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274):

- Pope Leo XIII in 1879 declared Aquinas’ philosophy to be the true Catholic philosophy. Whereas Augustine built upon Plato’s theories, Aquinas used Aristotle for his foundation. A major difference, however, between Aquinas and the Greeks, was his support of a division between philosophy and religion. He argued that philosophy was based on reason, whereas religion was based on truths of revelation and held by faith. (Note that John Paul II discussed this reconciliation as a contemporary concern in his encyclical “Faith and Reason”).

- Aquinas’ project predominately endeavors to systematize the ideas in the works of the Church fathers and work out a consistent theology. Nonetheless, he incorporates numerous new interests and pieces of knowledge into religion as he reconciles the Christian notions of God with Greek philosophy. He argues that truth can be known both by reason and by faith; thus, reason is a tool for faith.

- Aquinas held that the nature of humanity is essentially what Aristotle’s De Anima argues: one is a natural being with natural functions and has natural ends, yet, he adds that each is also a child of God and thus has a supplemental end: loyalty and obedience to God.

- Aquinas held that the nature of God is also both like and more than what Aristotle had argued; that He is the supreme: pure actuality, pure intelligence, and a being whose perfection inspires the universe’s movement, yet adds that God is also creative providence, loving father, and exacting ruler.

- John Duns Scotus (1265/6-1308):

- A Scottish philosopher likely educated in England (reputedly Cambridge and Oxford, as well as Paris) and ordained a Franciscan priest in Northampton, England; he lectured in Paris, in between expulsions for political-theological disputes, and in Cologne, where he died in 1308. He was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1993. He is the founder of “Scotism,” a form of Scholasticism; also dubbed “Doctor Subtilis,” for the delicate nuance of his thought, almost to the charge of sophism. His intellectual legacy includes doctrines on the “univocity of being” (existence is most abstract and applies to all; follows Aristotle’s assertion that the subject matter of metaphysics is being qua being; his doctrine denies a real distinction between essence and existence (contra Aquinas), that is, between whether something is and what it is), the “formal distinction” (distinguish different aspects of same thing), “haecceity” (that which individuates a thing), a proof for the existence of God (an a posteriori proof, proceeding from His effects; uses a causal argument), and argument for Mary’s immaculate conception (which caused tremendous opposition).

III) The Late Middle Ages (ca. 1300-1453):

Philosophy in the 14th c. is often characterized by its contrast to the earlier centuries, thus as a decline of such philosophy and rise of a destructive critique. There was a more or less firm solidification of philosophy into competing schools: the Thomists, Scotism, Albertism, and Nominalism. There is also the argument for the divorce of philosophy from theology, which would signal the end of Scholasticism and the end of medieval philosophy. There was also a growing doubt in metaphysical presumptions to knowledge and a more welcoming stance to empiricism (as is notable in Early Modern philosophy). In general, the attention had been turned from the relation of the soul to knowledge as an activity to knowledge as demanding evidence and seeking claim to validity and/or certainty. By the 15th c., philosophical debates had divided the “older way” (via antiqua) from the “modern way” (via moderna) of thinking. This modern way was predominately nominalism, and bolstered by Ockham and Buridan.

14th Century:

William of Ockham: (and following him, the Ockhamist School)

Nicholas of Autrecourt

Marsilius of Padua

John Buridan

Transition to Modern Philosophy

Triumph of an Academic

Key Philosophical Ideas

Neoplatonism:

Neoplatonism (New-Platonism) establishes a mystical interpretation of Plato as a base for further philosophical work; it was the predominate influence for Abrahamic philosophy until the mid to late middle ages. It relies upon Plato’s Timaeus, Parmenides, and unwritten doctrines (purportedly most discussed). Plato’s nephew, Speusippus (ca. 407-339 b.c.e.), the first diadochus (head successor) for the Academy, codified these teachings into that on what would become the focus of the middle ages; their basis is in Pythagorean theory and expound first principles of the cosmos as the Monad and Dyad (the One above Intellect, beyond being, and the Many); equally important is World-Soul, similar to Plato’s Demiurge, who mediated the ideal and matter to create the elements, which expands the dualism into a tripartite metaphysical system. In essence: there is first the Monad over against the infinite Dyad from which all multiplicity comes; this dichotomy produces Number, “by reason of a certain persuasive necessity,” in order to provide the “principle of infinite divisibility,” which operates by an elaborate geometry to then create all that is.* Within multiplicity’s realm of World-Soul, Speusippus claims that goodness become apparent.** The good is a creative power, a demiurgic activity of the World-Soul and echoes the Timaeus’ characterization of the goodness of the Demiurge as the “agent of all order and tendency towards perfection in the physical universe. …”*** The creative infusion of goodness through a tripartite system gives medievals their ground from which to conceptualize variant renderings of hierarchy and agency. Neoplatonism’s cosmology gives, then, the basis to create structures (of meaning, for the sciences, of nature, people, etc.), which allows a narrative plot for ethical, social, political, religious, and aesthetic theories.

- * Speusippus, quoted in Dillon, Heirs of Plato, 44, and Dillon himself, respectively. All that is includes multiplicity’s creation of the realm of Soul, responsible for geometrical extension, the generation of all other souls in the universe, the physical world, celestial bodies, earthly body, thought, language, instinct and passions, the Good, and motion and repose (Ibid., 40-53).

- ** Goodness, evil, all other Platonic Forms are housed within the World-Soul (such prohibited in highest realms: he “wished to deny ‘goodness’ both to the primal One, and even to the mathematical and geometrical levels of reality, not because they were bad, but simply because he felt that the term had no real meaning at those levels” (Ibid., 53)).

- *** Ibid., 4. Cf., Plato, Timaeus, 29e.

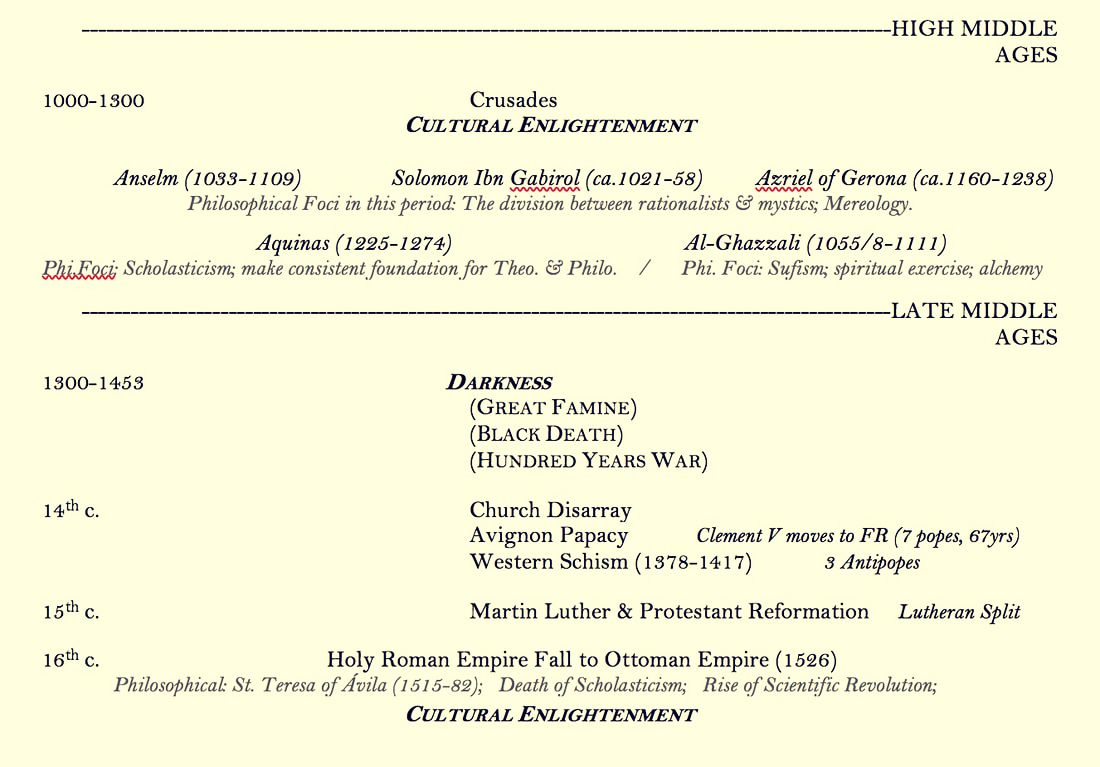

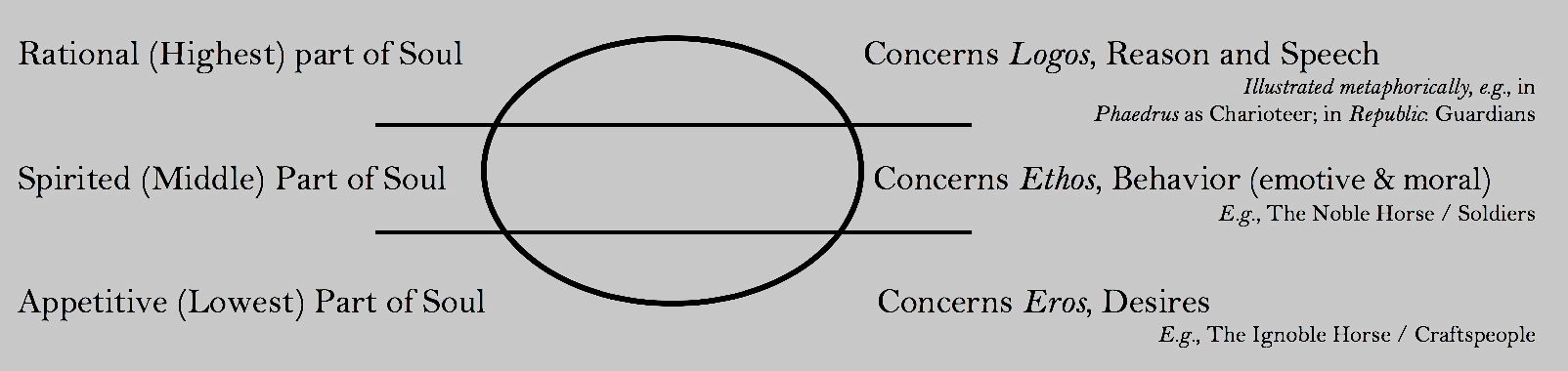

Three Conceptions of Soul:

The following charts demonstrate three Conceptions of Soul: Plato’s, Aristotle’s, and Aquinas’. All three are tripartite models; their fundamental divisions remain fairly similar while their conception changes from a more mythic explanation to biological characterization. However, the philosophical import to attend to here can be grasped by thinking these three conceptions in relation to Augustine as a preeminent example of Neoplatonism’s synthetic nature. Augustine is Platonist on most matters, but his idea of soul is closest to Aristotle’s and became the model further elaborated by Aquinas, and therefore the canonical exemplar of the Christian conception of soul. Augustine is therefore himself a model of Neoplatonism in the sense of synthesizing diverse inheritances (Platonic and Aristotelian) with developed commitments (Christianity) and bequeathing it to later generations (Aquinas) and thus to Christian dogma and tradition and thereby as the presumptive model for Western (scientific, psychological, spiritual) belief systems.

Plato’s Soul:

The following charts demonstrate three Conceptions of Soul: Plato’s, Aristotle’s, and Aquinas’. All three are tripartite models; their fundamental divisions remain fairly similar while their conception changes from a more mythic explanation to biological characterization. However, the philosophical import to attend to here can be grasped by thinking these three conceptions in relation to Augustine as a preeminent example of Neoplatonism’s synthetic nature. Augustine is Platonist on most matters, but his idea of soul is closest to Aristotle’s and became the model further elaborated by Aquinas, and therefore the canonical exemplar of the Christian conception of soul. Augustine is therefore himself a model of Neoplatonism in the sense of synthesizing diverse inheritances (Platonic and Aristotelian) with developed commitments (Christianity) and bequeathing it to later generations (Aquinas) and thus to Christian dogma and tradition and thereby as the presumptive model for Western (scientific, psychological, spiritual) belief systems.

Plato’s Soul:

Soul and Body are of two distinct natures (mostly accords with Augustine’s version of soul).

Soul is distinct from, not unique to, the mortal body (mostly vs. Augustine’s version of soul, which is personal).

Soul is immortal; however, details of the where and how as are ambiguous, e.g., Apology’s two proposals for after bodily death (like an eternal sleep and transmigration of soul to realm where Socrates could interrogate all past heroes) leave questions (sleep: just body, or soul, too, and if soul is distinct, while body sleeps in ground, where does the soul ‘sleep’?; and other realm: either soul is self, and thus personal, yet not same as body, and thus a collective of bodiless selves hang out in this other realm, or else it suggests contradiction of soul’s distinction), and further questions arise comparing these ideas to Republic’s ‘myth of Er’ and Phaedrus’ account of self which suggest a truer transmigration of souls so that who/what one is is determined by who/how one was in one’s previous incarnation. In Phaedo, Socrates proposes at least four arguments affirming soul’s immortality and that its afterlife is a contemplation of truths, although it is uncontroversial to say that the arguments do the opposite of squashing all skepticism. (Both accordances and contradictions to Augustine’s version.)

Soul is distinct from, not unique to, the mortal body (mostly vs. Augustine’s version of soul, which is personal).

Soul is immortal; however, details of the where and how as are ambiguous, e.g., Apology’s two proposals for after bodily death (like an eternal sleep and transmigration of soul to realm where Socrates could interrogate all past heroes) leave questions (sleep: just body, or soul, too, and if soul is distinct, while body sleeps in ground, where does the soul ‘sleep’?; and other realm: either soul is self, and thus personal, yet not same as body, and thus a collective of bodiless selves hang out in this other realm, or else it suggests contradiction of soul’s distinction), and further questions arise comparing these ideas to Republic’s ‘myth of Er’ and Phaedrus’ account of self which suggest a truer transmigration of souls so that who/what one is is determined by who/how one was in one’s previous incarnation. In Phaedo, Socrates proposes at least four arguments affirming soul’s immortality and that its afterlife is a contemplation of truths, although it is uncontroversial to say that the arguments do the opposite of squashing all skepticism. (Both accordances and contradictions to Augustine’s version.)

Mysticism:

Mysticism: immediate, direct, intuitive knowledge of God or ultimate reality attained through personal religious experience, which may be complete return or via a single or series of brief encounters, dreams, or visions whose continuum of contact proportionate to received knowledge (from indubitable to scant, veiled).

- Etymology: Greek mysterion (“secret rite or doctrine”) from mýstēs (“one who has been initiated”) from verb mýein (“to close” or “to shut,” i.e., closing of the lips so as to keep a secret, shutting of the eyes because only the initiated allowed at sacred rites, hence its enigmatic ‘knowledge’ neither had as reason or normal sense data).

Mystical Methods of Naming (Knowing):

- Cataphatic Theology: (affirmative theo) ascription of confirmatory names to God w/o equivocation: God is Light.

- Apophatic Theology: (negative theology) ascription of negative names to God or negation of the possibility of affirmative names: God is not Light.

Why?: One seeks to know that something is, what it is, how it is, and why it is; establishing ‘that’ is to establish a name, which then gives insight to ‘what’, from which to induce/deduce ‘how’ and ‘why’ (supported by Emanation Theory). The greatest epistemic challenge is God, who is “nameless and yet has the names of everything that is,” and, “Since the unknowing of what is beyond being is something above and beyond speech, mind, or being itself, one should ascribe to it an understanding beyond being,” hence the focus on naming (Pseudo-Dionysius, Divine Names, 596C, 588A).

Theory of Emanation:

Etymology: emanation: “to flow forth or stream;” indicates how causality divinely pours forth; visualized as streams, bubbling water, fountains, cycle of clouds producing rain evaporating back into clouds.

History: ancient (pre-Presocratic) Egyptian roots, flourished in pagan Neoplatonism (ca. 204 c.e. (Plotinus’ birth)-529 c.e. (Justinian’s closure of Plato’s Academy)), adopted by Abrahamic traditions.

First principle: all derived things (the dyad, the many) proceed out of an originary source (the monad).

Theory: everything that is (dyad), before it is (before creation), is the One (monad); the One creates by “procession,” an overflowing; the overflow is creation, which, by nature is the one-become-many, hence by nature seeks “reversion,” a return to the One; the procession-reversion cycle is driven by desire:

Philosophically Yields: a metaphysics: Cosmology (account of universe’s origin, power/activity of creation); ontology (gives account of being: everything that is, is of the One); epistemology (gives a way to understand creation & creator by knowing dyad as of the monad); teleology (gives end (purpose, goal): return to the One); ethic (gives duty: make self worthy of return via rational exercise/spiritual practice).

Abrahamic Instantiation: emanation as creation infinitely expands the idea of Adam as “created in His image” (Genesis 1:27) to say everything is created in His image, as His image, by His image, and will end in His image with a return to Him. Piety dictates mental and lived pursuit of God.

Etymology: emanation: “to flow forth or stream;” indicates how causality divinely pours forth; visualized as streams, bubbling water, fountains, cycle of clouds producing rain evaporating back into clouds.

- Iamblichus: “ever-flowing and unfailing creativity;” Proclus: “Every effect remains in its cause, proceeds from it, and returns to it;” Damascius: effect “flowing” from its cause; Pseudo-Dionysius: Cherubim as “effusion of wisdom,” God and His attributes as “outpouring” to His creatures, God’s creativity as “bubbling over” and “bubbling forth;” Romans 11:36: “From him and to him are all things.”*[1]

- * Cf., Stephen Gersh, From Iamblichus to Eriugena: An Investigation of the Prehistory and Evolution of the Pseudo-Dionysius Tradition (Leiden, The Netherlands: E.J. Brill, 1978), 17-19; Thérèse Bonin, Creation as Emanation: The Origin of Diversity in Albert the Great’s On the Causes and the Procession of the Universe (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame, 2001), 15-21; Proclus, The Elements of Theology, ed. E.R. Dodds (Oxford: Clarendon, 1963), nos. 35, 38; Pseudo-Dionysius, The Divine Names, 952A; passage from Romans also cited by P-D in Celestial Hierarchy, 121A.

History: ancient (pre-Presocratic) Egyptian roots, flourished in pagan Neoplatonism (ca. 204 c.e. (Plotinus’ birth)-529 c.e. (Justinian’s closure of Plato’s Academy)), adopted by Abrahamic traditions.

First principle: all derived things (the dyad, the many) proceed out of an originary source (the monad).

Theory: everything that is (dyad), before it is (before creation), is the One (monad); the One creates by “procession,” an overflowing; the overflow is creation, which, by nature is the one-become-many, hence by nature seeks “reversion,” a return to the One; the procession-reversion cycle is driven by desire:

- “Because it [God/The One] is there the world has come to be and exists. All things long for it. The intelligent and rational long for it by way of knowledge, the lower strata by way of perception, the remainder by way of the stirrings of being alive and in whatever fashion befits their condition” (Pseudo-Dionysius, DN 593D).

Philosophically Yields: a metaphysics: Cosmology (account of universe’s origin, power/activity of creation); ontology (gives account of being: everything that is, is of the One); epistemology (gives a way to understand creation & creator by knowing dyad as of the monad); teleology (gives end (purpose, goal): return to the One); ethic (gives duty: make self worthy of return via rational exercise/spiritual practice).

Abrahamic Instantiation: emanation as creation infinitely expands the idea of Adam as “created in His image” (Genesis 1:27) to say everything is created in His image, as His image, by His image, and will end in His image with a return to Him. Piety dictates mental and lived pursuit of God.