The weeds appearing over the last year in my little Nashville yard have proved so, so many, a second page of their inventory is now required ...

|

PAGE ONE (link ~~HERE~~ & at bottom):

1) Plantain (Plantago major) 2) Creeping Charlie (Glechoma hederacea) 3) Smilax (Smilax rotundifolia or S. bona-nox) 4) Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana) 5) Porcelainberry (Ampelopsis brevipedunculata) 6) Bush / Amur Honeysuckle (Lonicera Maackii) 7) Privet (Ligustrum sinense) 8) Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) 9) Wintercreeper (Euonymous fortunei) 10) Ivy (Hedera helix) 11) Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana and Duchesnea indica) 12) Violets (Viola spp.) 13) Speedwell (Veronica officinalis or V. americana) 14) Dock (Rumex spp.) 15) Buttercups (Ranunculus acris) 16) Crown vetch (Securigera varia) 17) Spurge (Euphorbia humistrata or E. maculata) 18) Bedstraw / Cleavers (Galium aparine) 19) Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) 20) Virginia Threeseed Mercury (Acalypha virginica) 21) Pennsylvania Smartweed (Polygonum pensylvanicum) |

22) Pigweed (Amaranthus palmeri)

23) Virginia Buttonweed (Diodia virginiana) 24) Oxalis (Oxalis stricta) 25) Creeping Cucumber (Melothria pendula) 26) Whitestar / Small White Morning Glory (Ipomoea lacunose) 27) Bindweed (Convolvus arvensis) 28) Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans or T. rydbergii) 29) Fleabane (Erigeron annuus or E. strigosus) PAGE TWO: 30) Pilewort (Erechtites hieraciifolius) 31) Lamb’s Quarters (Chenoposium album) 32) Swamp Rose-Mallow and Rose of Sharon (Hibiscus moscheutos and H. syriacus) 33) Mystery Umbellifer: Wild Carrot (Daucus carota), Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca), Field Hedge Parsley (Torilis arvensis) 34) Mystery Asteraceae: Black- and Brown-Eyed Susans (Rudbeckia hirta and R. triloba) 35) Mystery Giant: Giant Ragweed (Ambrosia trifida) 36) Sweet Annie (Artemisia annua) 37) Mulberry Weed (Fatoua villosa) 38) Red Mulberry Tree |

39) Hackberry Tree (Celtis occidentalis)

40) American Elm (Ulmus americana) 41) White and Southern Red Oaks (Quercus Alba and Quercus falcata) 42) Cross Vine (Bignonia capreolata) 43) Star of Bethlehem (Ornithogalum umbellatum) 44) Garlic Chives (Allium tuberosum) 45) Late-Flowering Thoroughwort (Eupatorium serotinum) 46) Figwort (Scrophularia marilandica) 47) Italian Arum (Arum italicum) 48) Cranesbill (Geranium, likely G. carolinianum or G. bicknellii) PAGE THREE (Link ~~HERE~~ & at bottom): 49) Red Dead-Nettle (Lamium purpureum) 50) Chickweed (Stellaria media) 51) Crow Garlic (Allium vineale) 52) Little-leaf or Fig-leaf Buttercup (Ranunculus abortivus) 53) Smallflower Baby Blue Eyes (Nemophila aphylla) 54) Black Medic (Medicago lupulina) 55) Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) 56) Perilla (Perilla frutescens) 57) Oriental False Hawksbeard (Youngia japonica) |

30)

|

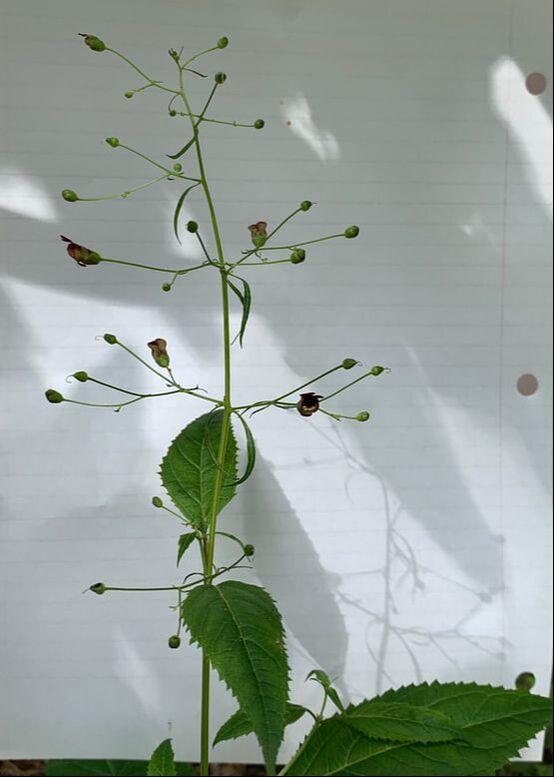

Pilewort (Erechtites hieraciifolius): You of the Asteraceae family, with a genus name dating from 1817 and possibly owing to its usually dissected leaves from erechtho, the Greek “to rend, break,” or to the fabled king of Attica, Erechtheus, or Gaia’s rather accidently conceived son by Hephaestrus’ attempt on Athena, named Erichtonius, from the Greek erextho, “trouble,” and ethon, “earth;” its most common common name, pilewort, is likely due to how its unusual bud-like flowers fade to seeds with white tufts that may have been used as pile in bedding or toys, although two other common names, fireweed and American burnweed, identify its preference for scruffy, disturbed habitats, especially those rather sunny and moist.* Pilewort’s leaves vary notably—lanceolate, ovate, oblanceolate, pinnately lobed or nearly full or irregularly serrated, alternate to spiraling on round stems, ranging from three to eight inches, lower ones come from short petioles, the upper are sessile, clasping close to the stem—so it is by the weed’s unique flowers that sure identification can be made. They arise from the uppermost stems as panicles of flowerheads, each much

|

|

like a small dandelion minus all the petal-show—well, nearly all, a hint of white fluff can be barely seen, flowers that appear as if they have already fallen to seed, which does soon happen, producing easily wind-riding wispy seeded tufts. These widespread North and South American native weeds tend to form clumps and branch, and can grow from two feet to well upwards of six, but they are an annual, and while producing far-flying seeds, they also tend to disappear from newly burned or disturbed areas when other weeds bully in too close. While the leaves have an unpleasant odor that keep munching mammals from grazing it, wasps of various types particularly appreciate its nectar. Its human edibility has been debated, with some being disturbed by an old study showing the presence of liver-damaging chemicals in it, others turned off by its rather foul odor, and others declaring it delicious.**

* Genus etymology from Michael L. Charters’ extensive compilation of plant names’ histories, available ~~HERE~~; and Eat the Weeds page, available ~~HERE~~; common names’ explanation from The Illinois Wildflowers information page, available ~~HERE~~. ** Cf., Illinois Wildflower information page, available ~~HERE~~; Native and Naturalized Plants of the Carolinas and Georgia page, available ~~HERE~~; North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox page, available ~~HERE~~; and Eat the Weeds page, available ~~HERE~~. |

31)

Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium): likely C. album, although possibly C. suecicum given you broader, smaller leaves and less noticeable white fuzz on new ones, or C. missouriense, said to be native to the south-central U.S.. The genus, named by Linnaeus, is the Greek chen, “goose,” plus pous, “foot,” hence commonly called the goosefoots, in reference to their leaf shapes; other common names for the several species noted include pigweed, fat hen, and wild spinach.

This summer annual’s leaves are often alternate about the stems, typically one to four inches in length and a couple wide, in variable shapes, triangles to diamonds to egg-like to more lance sleek, some varieties tending to become lobed, on long, slender petioles, with irregular large toothing margins on most but the topmost, newest leaves, although the characteristic feature to identifying lamb’s quarters is their leaves’ pale, whiteish to blueish fuzz, occasionally taking on a pink hue barely ringing its edges—which appears mostly absent in the samples about my yard. The flowers are spike-like, branching arrangements, with some photographs almost reminiscent for me of a petite cream-colored astilbe. My specimens are rarely more than a foot tall, but there are many reports of lamb’s quarters towering out around six feet tall. Besides noticing it due its possible height, the plant is usually found in impressive numbers due to each’s ability to produce nearly 50,000 wind-pollinated seeds that can remain viable for 40 years (although Richard Mabey reports on some 1,700 year old seed from an archeological site being sprouted). Its long proliferation—Mabey notes archeological digs in England finding evidence of it as early as the Bronze Age (2000-500 b.c.e.)—may also be due to its most favored land (well disturbed, its tap root permitting it to survive even in very scruffy plots, and its ability to chemically suppress nearby growth of some crops like cabbages, tomatoes, and carrots) and for being a long favored human-foraged plant. Mabey proposes it may have been cultivated in the Iron Age (the end of the Bronze Age), as further evidenced the prolific usage of melde, its Old English name, for settlements in the U.K. through the Middle Ages. Being in the Amaranthaceae family, its seeds can be ground to flour or eaten similarly to quinoa (and are also well enjoyed by sparrows, fall field crickets, some grasshoppers, and other bugs), and its leaves eaten like spinach, raw or cooked (which are also (well, in raw form) enjoyed by many moth and butterfly caterpillars, and are notably capable of drawing away leaf miners from beet or chard crops). While high in oxalates and saponins, the leaves and seeds have impressive nutritional profiles, notably for their calcium, iron, and vitamins A and C.*

This summer annual’s leaves are often alternate about the stems, typically one to four inches in length and a couple wide, in variable shapes, triangles to diamonds to egg-like to more lance sleek, some varieties tending to become lobed, on long, slender petioles, with irregular large toothing margins on most but the topmost, newest leaves, although the characteristic feature to identifying lamb’s quarters is their leaves’ pale, whiteish to blueish fuzz, occasionally taking on a pink hue barely ringing its edges—which appears mostly absent in the samples about my yard. The flowers are spike-like, branching arrangements, with some photographs almost reminiscent for me of a petite cream-colored astilbe. My specimens are rarely more than a foot tall, but there are many reports of lamb’s quarters towering out around six feet tall. Besides noticing it due its possible height, the plant is usually found in impressive numbers due to each’s ability to produce nearly 50,000 wind-pollinated seeds that can remain viable for 40 years (although Richard Mabey reports on some 1,700 year old seed from an archeological site being sprouted). Its long proliferation—Mabey notes archeological digs in England finding evidence of it as early as the Bronze Age (2000-500 b.c.e.)—may also be due to its most favored land (well disturbed, its tap root permitting it to survive even in very scruffy plots, and its ability to chemically suppress nearby growth of some crops like cabbages, tomatoes, and carrots) and for being a long favored human-foraged plant. Mabey proposes it may have been cultivated in the Iron Age (the end of the Bronze Age), as further evidenced the prolific usage of melde, its Old English name, for settlements in the U.K. through the Middle Ages. Being in the Amaranthaceae family, its seeds can be ground to flour or eaten similarly to quinoa (and are also well enjoyed by sparrows, fall field crickets, some grasshoppers, and other bugs), and its leaves eaten like spinach, raw or cooked (which are also (well, in raw form) enjoyed by many moth and butterfly caterpillars, and are notably capable of drawing away leaf miners from beet or chard crops). While high in oxalates and saponins, the leaves and seeds have impressive nutritional profiles, notably for their calcium, iron, and vitamins A and C.*

Another species of Chenopodium, the C. vulvaria, unkindly but aptly called the stinking goosefoot or notchweed, is wonderfully honored in Alice Oswald’s poem entitled by that former common name, beginning “Stinking Goose-foot has grown human / It could happen to anyone,” and including the endearing later stanza: “And the little mealy lines of his veins / show what a trouble it’s been / to be quite this strange.”**

* Cf., Michael L. Charters’ compilation of plant names, available ~~HERE~~; Global Biodiversity Information Facility page, available ~~HERE~~; Minnesota Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; Illinois Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; The Brooklyn Botanical Garden page, available ~~HERE~~; Richard Mabey, Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants (New York: Harper-Collins, 2010), 32, 49-51, 79-80; on edibility, cf., the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners page, available ~~HERE~~; the Chestnut School of Herbal Medicine page, available ~~HERE~~; Food Print page, available ~~HERE~~.

** Alice Oswald, “Stinking Goose-foot,” collected in Weeds and Wild Flowers (London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 2009).

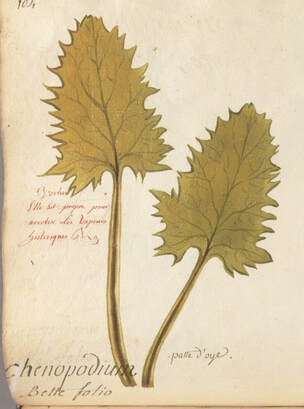

Herbal Manuscript Image: A different species of Chenopodium, [Botanical manuscript of 450 watercolors of flowers and plants]. approximately 1740. RARE-FOLIO QK98.2 .B683 1740. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, D.C. Available ~~HERE~~.

* Cf., Michael L. Charters’ compilation of plant names, available ~~HERE~~; Global Biodiversity Information Facility page, available ~~HERE~~; Minnesota Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; Illinois Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; The Brooklyn Botanical Garden page, available ~~HERE~~; Richard Mabey, Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants (New York: Harper-Collins, 2010), 32, 49-51, 79-80; on edibility, cf., the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners page, available ~~HERE~~; the Chestnut School of Herbal Medicine page, available ~~HERE~~; Food Print page, available ~~HERE~~.

** Alice Oswald, “Stinking Goose-foot,” collected in Weeds and Wild Flowers (London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 2009).

Herbal Manuscript Image: A different species of Chenopodium, [Botanical manuscript of 450 watercolors of flowers and plants]. approximately 1740. RARE-FOLIO QK98.2 .B683 1740. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, D.C. Available ~~HERE~~.

32)

|

Swamp rose-mallow and Rose of Sharon (Hibiscus moscheutos and Hibiscus syriacus): you are in the 5,000+ species Malvaceae family, and while both are often called hardy hibiscus, their common names typically blur together and include ‘mallow’ (‘Hibiscus’ being the ancient Greek and Latin name for a mallow-like plant), e.g., rosemallow, mallow rose, swamp mallow, marsh mallow, and to those variations the greater descriptions of crimson-eyed, eastern, wooly, and common, plus a range of others, like wild cotton, sea hollyhock, shrub althea; the former’s species name is derived from the Latin for ‘musk-scented,’ whereas ‘syriacus’ refers to its identification in Syrian gardens.

While the former are a little smaller and bushy, more water’s edge-inclined, these two Hibiscus look most similar, and, I discovered, are often confused for one another in collaborative gardening forums and commercial sites online, with the overlap of many of their common names, which are included on many reliable academic and governmental online resources, perhaps promoting confusion (further, many of the latter reliable sites permit users to upload photos that may not be rigorously vetted). While not a horticulturalist and therefore very tolerant of getting at least close in my identifications, the importance of precision really struck me concerning these Hibiscus because many feelings concerning ‘weeds’ fork dramatically if the plant in question can be called a native (and native plants will better support one’s native bugs), and, here, that is precisely what the former, H. moscheutos, is, whereas the latter, H. syriacus, has a native range from China to India. However, most are surprised to learn that our most common weeds, like plantain and dock, are not native, although can easily be called naturalized aliens, and my light but diverse research and attentive eyes have seen all manners of local wildlife enjoying them greatly. Whether H. syriacus can be called naturalized is a question I cannot answer, but the pollen-laden drunken bees I watch all over it does give the plant a reprieve in my reckoning. Given the similarity of most of the two species’ characteristics, I will describe both together, adding differentiations when needed. |

These stunning herbaceous perennials, which often resemble a bushy shrub or slim tree (commonly growing five to seven feet, although I have two long and lean rose of sharon that tower at 15 feet to seek the sun between some bradford calorie pears, cherry, and a tall wooden fence), bear attractive tooth-margined but notably variably shaped leaves, sometimes whole heart-shaped tear drops growing up to eight inches long and four across on the rose mallow, and the rose of Sharon, varying still, but more so about half the size and deeply cut with one to five lobes. But it is really the flowers that make these hardy and remarkably humidity-tolerant plants stand out: showy, beautiful flowers of four to six large delicately ruffling petals around a dramatic staminal column, quite resembling malvas or hollyhocks, but oversized, the rose of sharon trumpets the size of a cd about my yard with the swamp rose mallow and many hybrids getting up to the size of an lp, each lasting a day or two, but with a large bush supporting over a hundred buds, the show stretches from late summer to early fall. (The Plant Families guide describes their flowers as “often large, even gaudy, and make a striking addition to the yard,” specifically, “the tough-as-nails rose of Sharon shrub (Hibiscus syriacus) will bloom profusely, while cultivars of the cold-hardy rose mallow (H. moscheutos) will shock your friends with blooms the size of dinner plates.”*) Around my yard, the rose of sharon are pale lavender and white examples that are solid and variations with their deep fuchsia-magenta eye, however you will also find bright pink and red flowers on the rose mallows and others. I rarely come across a flower that is not vibrating with drunken bees—honeys, bumbles, carpenters, solitary—and these fantastic flowers are also attractors of hummingbirds, and host 28 species of butterfly and moth caterpillars. After its floral show, its large seedpods are also attractive, nearly sculptural, especially after the plant drops its leaves in fall, its pods drying to brown and cracking open to release its seeds when the cool weather comes. As some of its common names suggest, the rose mallow likes swampy soils, although both are quite tough, with the rose of sharon popping up in some of the driest areas of my yard, fighting it out for the sun amidst a scruffy, rocked and driveway edged honeysuckle and Euonymous clad property line. For those growing rose mallows along the shore or creeks, their thick and buoyant seeds—about 120 per each seed capsule—can travel far and be germinated far into the future, and numerous birds, from bobwhites to wood ducks, dine on the seeds, while red-winged blackbirds use them for nesting grounds. I have noticed the dramatically patterned and colorful bugs (six legged, long antennae, amber headed and red or white bodies well dotted, splotched, and lined in black, brown, white, and red) called Niesthrea louisianica, or simply the Hibiscus Plant Bug, decimating the dried seed pods—they are purposefully introduced sometimes to control another mallow called velvet leaf that has taken over crops—but these tough Hibiscus seedlings are still so rampant about my yard, I don’t interfere with the bugs’ seed feastings. While, as noted above, H. syriacus has a native range from China to India, despite being found profusely through the states, the Hibiscus moscheutos is native to the eastern U.S. from the Gulf of Mexico up to southern Ontario (although now found all the way to California), and was selected as 1997’s Wildflower of the Year for North Carolina and even winning a place on the Sundeck and Water Garden on Piet Oudolf’s High Line Gardens (upper level, W. 14th st. to W. 15th st.).** With the Hibiscus genus including natives from diverse regions, it is not surprising to find its mention in medieval European herbals—however, some may just be identifying its close cousin Malva moschata, musk mallow, which the RHS book Weeds calls “a beautiful native wildflower, one of the most garden-worthy of all,”*** or the Malva sylvestris, which Medicinal Plants in Folk Tradition notes as so long and widely distributed whether it was native to the British Isles is unknown, and for being most confusingly and frequently called ‘marsh-mallow’†—for example, according to the Old English Herbarium, “Many authorities attest to the efficacy of this plant” for treating gout, rendering it healed after just three days of a poultice of hibiscus pounded into aged lard; moreover, “For any accumulation of diseased matter on the body,” all a cure needs is boiling this plant with cress, linseed, and flour, which accords with Pliny’s prescription and the British Isles folk medicine traditions for it being “a general cleansant of the system.”††

It is also worthwhile to note a final nominal challenge, beyond ‘hardy hibiscus’ or a variation on ‘mallow’ blurring these two species and others: it is with the specific common name ‘rose of sharon.’ Recall how the maiden in Song of Solomon sings “I am a rose of Sharon, a lily of the valleys. As a lily among brambles, so is my love among maidens” (Songs 2:1-2, NRSV). She certainly did not self-identify as Hibiscus syriacus; instead, a footnote cites ‘rose’ to be the Hebrew חֲבַצֶּ֫לֶת (chabatstseleth), or ‘crocus,’ the Darby translation records her as “a narcissus of Sharon,” the Wycliffe and Douay-Rheims 1899 as the generalist “flower of the field,” with Biblical encyclopedias and scholars proposing this flower to be everything from a Narcissus Tazetta or N. serotinas, saffron crocus, anemone, or mountain tulip (with other ‘rose’ references beyond Songs veering from a bulb plant to perhaps being oleander or rhododendron), or as Eleanor Anthony King explains, a name “applied to a number of plants which blossomed on the lands [in Sharon, along the Mediterranean] after the rains.”†††

It is also worthwhile to note a final nominal challenge, beyond ‘hardy hibiscus’ or a variation on ‘mallow’ blurring these two species and others: it is with the specific common name ‘rose of sharon.’ Recall how the maiden in Song of Solomon sings “I am a rose of Sharon, a lily of the valleys. As a lily among brambles, so is my love among maidens” (Songs 2:1-2, NRSV). She certainly did not self-identify as Hibiscus syriacus; instead, a footnote cites ‘rose’ to be the Hebrew חֲבַצֶּ֫לֶת (chabatstseleth), or ‘crocus,’ the Darby translation records her as “a narcissus of Sharon,” the Wycliffe and Douay-Rheims 1899 as the generalist “flower of the field,” with Biblical encyclopedias and scholars proposing this flower to be everything from a Narcissus Tazetta or N. serotinas, saffron crocus, anemone, or mountain tulip (with other ‘rose’ references beyond Songs veering from a bulb plant to perhaps being oleander or rhododendron), or as Eleanor Anthony King explains, a name “applied to a number of plants which blossomed on the lands [in Sharon, along the Mediterranean] after the rains.”†††

* Ross Bayton and Simon Maughan, Plant Families: A Guide for Gardeners and Botanists (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2017), 155-56.

** Cf., Michael L. Charters’ compilation of plant names’ histories, available ~~HERE~~ and ~~HERE~~; The Missouri Botanical Garden page, available ~~HERE~~; U.S.D.A.’s Fire Effects Information System report on the species, ~~HERE~~; The Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center’s page, ~~HERE~~; the North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox page, ~~HERE~~; on the bugs, cf., Mississippi State University’s Extension page, available ~~HERE~~; on its Highline location, cf., Piet Oudolf and Rick Darke, Gardens of the High Line: Elevating the Nature of Modern Landscapes (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2017), 130.

*** Gareth Richards, Weeds: The Beauty and Uses of 50 Vagabond Plants (London: Royal Horticultural Society and Welbeck Publishing Group, 2021), 122.

† David E. Allen and Gabrielle Hatfield, Medicinal Plants in Folk Tradition: An Ethnobotany of Britain and Ireland (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2004), 107-10.

†† Anne Van Arsdall, Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine, chapter five: “A New Translation of the Old English Herbarium” (New York: Routledge, 2002), 168, and David E. Allen and Gabrielle Hatfield, Medicinal Plants in Folk Tradition: An Ethnobotany of Britain and Ireland (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2004), 108.

††† Eleanor Anthony King, Bible Plants for American Gardens (New York: Macmillan Co., 1941), 94; and, for the Hebrew, Biblehub’s Strong’s Concordance, available ~~HERE~~.

** Cf., Michael L. Charters’ compilation of plant names’ histories, available ~~HERE~~ and ~~HERE~~; The Missouri Botanical Garden page, available ~~HERE~~; U.S.D.A.’s Fire Effects Information System report on the species, ~~HERE~~; The Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center’s page, ~~HERE~~; the North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox page, ~~HERE~~; on the bugs, cf., Mississippi State University’s Extension page, available ~~HERE~~; on its Highline location, cf., Piet Oudolf and Rick Darke, Gardens of the High Line: Elevating the Nature of Modern Landscapes (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2017), 130.

*** Gareth Richards, Weeds: The Beauty and Uses of 50 Vagabond Plants (London: Royal Horticultural Society and Welbeck Publishing Group, 2021), 122.

† David E. Allen and Gabrielle Hatfield, Medicinal Plants in Folk Tradition: An Ethnobotany of Britain and Ireland (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2004), 107-10.

†† Anne Van Arsdall, Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine, chapter five: “A New Translation of the Old English Herbarium” (New York: Routledge, 2002), 168, and David E. Allen and Gabrielle Hatfield, Medicinal Plants in Folk Tradition: An Ethnobotany of Britain and Ireland (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2004), 108.

††† Eleanor Anthony King, Bible Plants for American Gardens (New York: Macmillan Co., 1941), 94; and, for the Hebrew, Biblehub’s Strong’s Concordance, available ~~HERE~~.

33)

Mystery Umbellifer: Wild Carrot (Daucus carota L.), Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa L.), Field Hedge Parsley (Torilis arvensis):

|

One day in mid-summer, this knobby-kneed, gawky but growing giant appeared in my front garden bed. Your leaves, a little floppy and patchy, not quite as lacy as Queen Anne’s Lace, but attractive enough to surely point to your membership in the Apiaceae (or Umbelliferae) family.

Could you, my soon to be proved very prodigious visitor, be a Wild Carrot or Wild Parsnip (Daucus carota L. or Pastinaca sativa L.)?—which is, the Old English Herbarium instructs, a godsend for the ladies: either for cleansing or aiding difficult births, wherein either requires simmering the herb in water and bathing in and drinking it.* The Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) also appears in ethnobotany research on the Ojibwe native Americans as an aid for women; Huron Smith noted that they were “quite cautious in using this poisonous root. They claim that a little bit is very powerful, while much is poisonous,” hence use a very little mixed with other roots in a tea for “female troubles.”** |

For the gustative, instead of medicinal pot, Parsnips—known as pars-neeps or pasternaks—were long cultivated in England by the Romans and known well throughout France, making appearances in medieval recipes, occasionally in porray (a vegetable soup or stew) or compost (not the soil-making kind, but from Old French via the Latin compositus, ‘put together,’ a stew or preserved savory or sweet mix of cooked fruit and vegetables), but more often eaten fresh, cut up with apples and fried as fritters, or used to make parsnip wine.***

(Foragers beware, please: if you happen to come across a similar looking plant, but with purple or purplish splotches on its stem, you may be dealing with the skin-irritating and highly toxic invasive poison hemlock (Conium maculatum), and, attractive flowers aside, I highly recommend carefully disposing of the plant, especially before it sets seed.†)

As I let the plant grow on—and, oh my, did it—and remained uncertain of its exact ontological status, I was flipping through a plant catalogue from the farm where I have bought many daylilies when a picture jumped forth at me: a long, lovely row of gleaming golden hemerocallis in full bloom, and speckled heavily through like sugar sweetening up fresh lemonade were lacy white umbellifers—I believe that I have discovered the origin of the unknown not-quite-Queen-Anne’s-Lace-maybe-scruffy-Carrot-or-Parsnip specimens in my front bed. One possible spatial origin known spurred my thought I ought to know its denominative origin ... Then dawned August. A late-summer bed clean-up day. I have discovered a reason for which I must know its name, as I have learned its nature, and such has granted an undeniable reason for forbidding this unknown umbellifer’s reoccurrence (or, at least its ever setting seed again) …

|

In the picture, you can see the reason … and imagine just as heavy a smothering of prickly, scratchy, itchy, irritating seeds as on the gardening gloves all up and down one’s arms, throughout one's hair, covering one’s shirt, working their way under the hem, in the neck, up the sleeves, plus covering the jeans, clinging ferociously to socks, sticking in shoelaces … and laundering and drying one’s clothes does no good … they can only be removed one by one.

|

My identification motivation was ‘pricked’, one could say, but trying to identify this unknown umbellifer proved a prodigious challenge … flip with me through the field guides’ regional options in the Apiaceae (or Umbelliferae) family:

- Mountain Angelica (Angelica triquinata)—no, your umbels are too dense, your five-foot height just about right, but perhaps a peek tall;

- Water Hemlock (Cicuta maculate)—no, thankfully, you viciously poisonous giant, your pinnately compound leaves are too whole and thin;

- Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum)—no, again thankfully, you who poisoned Socrates, your leaves are too lacy;

- Queen Anne’s Lace (Daucus carota)—no, sadly, you have more delicate leaves, greatly dissected, your flowers are borne in majestic three to five inch wide umbels, held up and taut, with a speck of royal purple in the center;

- Cow Parsnip (Heracluem maximum)—no, your leaves are too massive, up to 12 inches long pinnately or palmately lobed, and you are said to have a most rank odour;

- Sweet Anise (Osmorhiza longistylis)—no, your scent is far lovelier than the above, and far more distinctive than my unknown flora visitor, although your umbels are more sparse like it;

- Cowbane (Oxypolis rigidior)—no, your leaves are too smoothly margined, too long and lean of lances, your umbel is too sparse, too petite;

- Big Mock Bishop’s Weed (Ptilimnium costatum)—no, your leaves are thread-like leaflets, and my front garden bed is no swamp or streambank;

- Field Hedge Parsley (Torilis arvensis)—oh, wait … “parsley” eh?, hardly petite and tasty, but also known as the spreading field parsley … and widespread in Tennessee … this may just be a candidate, although, granted, mine did reach higher than your reported three-foot statures … but, like you, widely branched, leaves with one to three times pinnate form, coarsely toothed … like you, flowers were small and white, borne in terminal and lateral umbels on long peduncles so to form five to nine umbellets … the flowers on mine appeared at the end of May, hence just a shave earlier than your reported June to July … the only question that remains in my mind is that your guidebook portrait makes you look so slim, wispy and nearly graceful, whereas my specimens were tough: stout yet towering, bulky yet delicately buoyant.††

Oh dear, see all the lime-colored greenery?, it's late October, our first frost hasn't come yet, and ~something~ has sprouted ~all~ over the front bed ... just imagine if my gardening gloves and socks hadn't carried off an extra several hundred seeds ...

Oh dear, see all the lime-colored greenery?, it's late October, our first frost hasn't come yet, and ~something~ has sprouted ~all~ over the front bed ... just imagine if my gardening gloves and socks hadn't carried off an extra several hundred seeds ...

So, what else can I find about this likely suspect?

Field Hedge Parsley (Torilis arvensis): your genus, Torilis, means ‘engraved,’ designating the grooves of your fruit, hidden beneath your sticky bristles, and you are also commonly called spreading hedge parsley, and your absolutely perfect name, according to North Carolina’s extension service and iNaturalist’s text co-opted from Wikipedia: ‘tall sock-destroyer’—though, you irredeemably claimed, from me, two socks and two sets of gardening gloves. You are an annual in the Apiaceae /Umbelliferae family imported from your wide spread throughout Eurasia, however, there is one report, on USwildflowers page, suggesting you are also native to British Columbia. Evidently you are present enough there to encourage Washington state to declare you an obnoxious weed, and are listed as invasive by California, Indiana, Kentucky, and Georgia, with this codified in state law by Wisconsin. Here in the States, beyond in my front garden beds, you are found widely through disturbed areas, waste areas, thickets, cleared woodlands, and along railroad lines and roadsides, preferring full sun and average to dry conditions, often liking gravel, including limestone. Your taproot is long, your seeds are many and spread so, so easily by clinging to anyone or thing that ventures near. You are praised for attracting bees and butterflies, pollinating flies and wasps, your foliage notably delighting the Black Swallowtail’s caterpillars, and providing the occasional snack for mammalian herbivores; and yet you are widely and roundly condemned for your viciously sticky seeds and promiscuous spreading habits (although your airy form doesn’t terribly crowd out neighbors). Reports somewhat differ on some of your salient features. For example, for your stature: you are said to erectly yet sprawling-ly grow to everything from one to three feet tall, six inches to a foot wide, and on slender, round stems that are either highly branching or just occasionally so. Your leaves are said to range from three to six inches wide, and stretch beyond six inches in length, their form being pinnately or bipinnately or palmately compound with trifoliate leaflets, each one to two inches long, on long petioles, your margins are either toothy or lobed, and together form a triangular or fern-like alternate spray, with those closest to the flowers being lanceolate or narrowly ovate and lightly hairy. Your flowers are normally pictured as white, but sometimes pink or with a reddish tinge, your umbels (composed of five to nine discrete umbellets that each has roughly eight five-petalled and five-stamened flowers of about three millimeters wide) stretch from two to three inches wide, and your blooming period is said to range from early to mid-summer. Each of your flowers produces a fruit that is variously described as white, pink, rosy-green, whitish-green, green, brown, or copper, and shaped as an oblong bur-like seed with straight to curving bristles—though, every listing agrees on their prodigious number and insane adhering powers. Helpfully, you have been identified as closely resembling the wild carrot, although can be differentiated by your smaller stature, earlier bloom time, and by the sparse, short white hair on your leaves and stems.†††

While this seems the likeliest candidate for my unknown umbellifer, my specimens grew to over four feet tall (at least 16 inches higher than the upper range in the guides), and appropriately had far more stout base stems reaching nearly ¾ of an inch in diameter. Perhaps mine were, though, simply quite happy in my full mid-southern sun and slightly underwatered garden beds.

Field Hedge Parsley (Torilis arvensis): your genus, Torilis, means ‘engraved,’ designating the grooves of your fruit, hidden beneath your sticky bristles, and you are also commonly called spreading hedge parsley, and your absolutely perfect name, according to North Carolina’s extension service and iNaturalist’s text co-opted from Wikipedia: ‘tall sock-destroyer’—though, you irredeemably claimed, from me, two socks and two sets of gardening gloves. You are an annual in the Apiaceae /Umbelliferae family imported from your wide spread throughout Eurasia, however, there is one report, on USwildflowers page, suggesting you are also native to British Columbia. Evidently you are present enough there to encourage Washington state to declare you an obnoxious weed, and are listed as invasive by California, Indiana, Kentucky, and Georgia, with this codified in state law by Wisconsin. Here in the States, beyond in my front garden beds, you are found widely through disturbed areas, waste areas, thickets, cleared woodlands, and along railroad lines and roadsides, preferring full sun and average to dry conditions, often liking gravel, including limestone. Your taproot is long, your seeds are many and spread so, so easily by clinging to anyone or thing that ventures near. You are praised for attracting bees and butterflies, pollinating flies and wasps, your foliage notably delighting the Black Swallowtail’s caterpillars, and providing the occasional snack for mammalian herbivores; and yet you are widely and roundly condemned for your viciously sticky seeds and promiscuous spreading habits (although your airy form doesn’t terribly crowd out neighbors). Reports somewhat differ on some of your salient features. For example, for your stature: you are said to erectly yet sprawling-ly grow to everything from one to three feet tall, six inches to a foot wide, and on slender, round stems that are either highly branching or just occasionally so. Your leaves are said to range from three to six inches wide, and stretch beyond six inches in length, their form being pinnately or bipinnately or palmately compound with trifoliate leaflets, each one to two inches long, on long petioles, your margins are either toothy or lobed, and together form a triangular or fern-like alternate spray, with those closest to the flowers being lanceolate or narrowly ovate and lightly hairy. Your flowers are normally pictured as white, but sometimes pink or with a reddish tinge, your umbels (composed of five to nine discrete umbellets that each has roughly eight five-petalled and five-stamened flowers of about three millimeters wide) stretch from two to three inches wide, and your blooming period is said to range from early to mid-summer. Each of your flowers produces a fruit that is variously described as white, pink, rosy-green, whitish-green, green, brown, or copper, and shaped as an oblong bur-like seed with straight to curving bristles—though, every listing agrees on their prodigious number and insane adhering powers. Helpfully, you have been identified as closely resembling the wild carrot, although can be differentiated by your smaller stature, earlier bloom time, and by the sparse, short white hair on your leaves and stems.†††

While this seems the likeliest candidate for my unknown umbellifer, my specimens grew to over four feet tall (at least 16 inches higher than the upper range in the guides), and appropriately had far more stout base stems reaching nearly ¾ of an inch in diameter. Perhaps mine were, though, simply quite happy in my full mid-southern sun and slightly underwatered garden beds.

* Anne Van Arsdall, Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine, chapter five: “A New Translation of the Old English Herbarium” (New York: Routledge, 2002), 184.

** Huron H. Smith, Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians (Milwaukee, WI: Order of the Board of Trustees, Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee, 1932), 366.

*** Teresa McLean, Medieval English Gardens (New York: The Viking Press, 1980), 209-10.

† Cf., King County Noxious Weeds identification page, available ~~HERE~~; and a general news alert from USAtoday, available ~~HERE~~.

†† Dennis Horn, Tavia Cathcart, Thomas E. Hemmerly, and David Duhl, Wildflowers of Tennessee the Ohio Valley and the Southern Appalachians (Auburn, WA: Lone Pine Publishing, 2018), 208-18.

††† Dennis Horn, Tavia Cathcart, Thomas E. Hemmerly, and David Duhl, Wildflowers of Tennessee the Ohio Valley and the Southern Appalachians (Auburn, WA: Lone Pine Publishing, 2018), 218; Illinois Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; iNaturalist page, available ~~HERE~~; USWildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; USDA page, available ~~HERE~~; Invasive.org inventory, available ~~HERE~~; Texas Invasives database, available ~~HERE~~.

... (Pictures Below): The following early spring: oh my, oh my ... the Field Hedge Parsley is ~T-A-K-I-N-G O-V-E-R~ everywhere ...

** Huron H. Smith, Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians (Milwaukee, WI: Order of the Board of Trustees, Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee, 1932), 366.

*** Teresa McLean, Medieval English Gardens (New York: The Viking Press, 1980), 209-10.

† Cf., King County Noxious Weeds identification page, available ~~HERE~~; and a general news alert from USAtoday, available ~~HERE~~.

†† Dennis Horn, Tavia Cathcart, Thomas E. Hemmerly, and David Duhl, Wildflowers of Tennessee the Ohio Valley and the Southern Appalachians (Auburn, WA: Lone Pine Publishing, 2018), 208-18.

††† Dennis Horn, Tavia Cathcart, Thomas E. Hemmerly, and David Duhl, Wildflowers of Tennessee the Ohio Valley and the Southern Appalachians (Auburn, WA: Lone Pine Publishing, 2018), 218; Illinois Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; iNaturalist page, available ~~HERE~~; USWildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; USDA page, available ~~HERE~~; Invasive.org inventory, available ~~HERE~~; Texas Invasives database, available ~~HERE~~.

... (Pictures Below): The following early spring: oh my, oh my ... the Field Hedge Parsley is ~T-A-K-I-N-G O-V-E-R~ everywhere ...

“To gardeners, the botanist’s definition of a flower—a shoot, modified for reproduction—may seem prosaic and hardly befitting the beauty of a hybrid rose or tropical orchid. But terse, factual, unsentimental descriptions are a part of scientific tradition. In truth, flowers are short branches bearing specially adapted leaves, and reproduction is the sole function for which flowers evolved; the pleasure they bring to people is coincidental.”

--Capon, however, may betray the unsentimental perspective by his attractive, descriptive writing immediately following:

“Flowers are also clever lures, not the innocent beauties poets would have us believe. Casting camouflage aside, most flowers ostentatiously advertise their presence. Brightly colored petals and fanciful shapes flash in vivid contrast to subdued, leafy backgrounds, beguiling insects and other small animals into close floral inspections. Floral aromas fill the air—whether sweet scents attracting bees or putrid odors to which carrion flies mistakenly flock. Convenient landing platforms, formed by petals, are provided for insects to rest from flight. And when the tiny animals are tempted to probe deeper into the flower’s structure, they become unwitting assistants in the plant’s reproductive process.”*

--Brian Capon, Botany for Gardeners (Timber Press), 175.

34)

Mystery Asteracea: Black-Eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta) and Brown-Eyed Susan (Rudbeckia triloba):

|

This initially unknown mass invader swept through my front garden three years ago, and has happily returned here and there at its own overpowering whim each spring-to-autumn since … in the spring, their tough and furry stems sport melodramatically lobed leaves, but the summer stretches them into immense wispy towers that eventually erupt in billowy but so sunny of billions of flowers: surely they are within the Asteraceae family, possibly a Helianthus, but, no, most likely a wild species of Rudbeckia. They are the iconic little-kid drawing of a flower—daisy-like done up in pure sunny gold—and permeate my longest memories of sun-drenched late summer gardens, so I was not surprised to read, in Andrea Wulf’s The Brother Gardeners, of the genus’ naming by Linnaeus for his old teacher Olof Rudbeck, the plant’s literal stature matching that of the person and professional achievements of his professor, its flowers, he said, bearing “witness that you shone among savants like the sun among stars”*—a remarkable honor, especially considering how crotchety the brilliant Linnaeus was said to be.

|

|

While the most common Rudbeckia is R. hirta, the Black-Eyed Susan—an absolute U.S. and Canadian native powerhouse of biodiversity and as utterly lovely as it is hardy, a one to two foot tall annual or short-term perennial with two to three inch yellow daisy-like flowers around a back center—I suspect my mystery specimen to be the native R. triloba, the Brown-Eyed Susan. This biennial or short-term perennial native to the eastern and midwestern U.S. differs from its relation, as indicated by its species name, triloba, by its irregular three-lobed basal leaves, and by its towering, two to five (some reporting up eight) foot bushy but airy stems and armies of much more petite, one to two inch flowers, their shorter but wider yellow petals surrounding a more notably coffee-brown eye. With so many blossoms per plant, the brown-eyed Susan can overpower small garden beds, but I have found that by mid to late summer when they come into bloom, most of my other flowers are spent and their plants comfortably hunkering down in the dappled shade they cast. |

While the literature I have found consistently identifies their petals as classic gold, my volunteers sported a range of variegation, solid gold flowers dancing alongside those with solid to inner-ringed bright penny copper to currant to milky-coffee brown hues (the sort you may see on cultivated varieties of R. hirta, like var. ‘Autumn Colors’ or R. triloba ‘Prairie Glow,’ but with pure haphazard variety per stem and all the wild non-cultivated features of the common triloba). Their striking variations, and bulk and floral profusion, are remarkably long lasting, with the last blooms outliving the first couple frosts of early winter. Saving some from the cold, I had cut branches bloom well and last long in a vase inside, and, when spent, their seeds were easy to harvest for scattering back in new corners of the yard. Otherwise, while their late-season appearance can be characterized as “untidy” (some generally referring to them all season as “coarse, weedy”), I find them to provide nice winter-interest, and have been long entertained by the happy finches working on the seed heads.**

Their innumerable blossoms unfailingly attract a diverse range of native bees and wasps, including bumbles, carpenters and diggers, cuckoos and leaf-cutters, Andrenid and Halictid bees, Sphecid and Vespid wasps, and even pollinating flies like Syrphids Tachinids, and thick-headed and bee flies.*** Douglas W. Tallamy’s inspiring Bringing Nature Home compellingly argues the case for native plants as a necessary foundation supporting, well, really, all life on our planet, but supplements his entomological case by appealing also to our aesthetic sides—doing this especially well with how Rudbeckia are doubly queens of the butterfly garden: “Along with their attractive floral display and nectar, rudbeckias support the reproduction of dozens of species of Lepidoptera [butterflies and moths], including the pearl crescent (Phyciodes tharos), silvery checkerspot (Chlosyne nycteis), and wavy-lined emerald (Synchlora aerata).”**** On my marvelous volunteers, I can confirm the favor the Silvery checkerspots pay it, but have also seen the Checkered white (Pontia protodice) and Gulf fritillary (Agraulis vanillae) butterflies drunkenly dancing between the golden flowerheads, as well as the equally captivating scamperings of Goldenrod soldier beetles’ orange and black bodies from flower to flower. Supporting biodiversity has never been so easy or lovely with the arrival of these billowy giants.

* Andrea Wulf, The Brother Gardeners: Botany, Empire, and the Birth of an Obsession (New York: Vintage Books, 2010), 124.

** On Black-Eyed Susans, cf.: Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center page, available ~~HERE~~; on Brown-Eyed Susans, cf.: Wisconsin Horticulture Division of Extension page, available ~~HERE~~; Illinois Wildflowers, available ~~HERE~~; Grow It Build It blog, available ~~HERE~~; Minnesota Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; Missouri Botanical Garden page, available ~~HERE~~.

*** Illinois Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~.

**** Douglas W. Tallamy, Bringing Nature Home: How you can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2021), 115.

* Andrea Wulf, The Brother Gardeners: Botany, Empire, and the Birth of an Obsession (New York: Vintage Books, 2010), 124.

** On Black-Eyed Susans, cf.: Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center page, available ~~HERE~~; on Brown-Eyed Susans, cf.: Wisconsin Horticulture Division of Extension page, available ~~HERE~~; Illinois Wildflowers, available ~~HERE~~; Grow It Build It blog, available ~~HERE~~; Minnesota Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; Missouri Botanical Garden page, available ~~HERE~~.

*** Illinois Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~.

**** Douglas W. Tallamy, Bringing Nature Home: How you can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2021), 115.

35)

Towering Mystery Weed: Giant Ragweed (Ambrosia trifida):

|

I had thought (wished?) on first encounter that this unknown weed was going to prove to be like the wild rudbeckia above, given its deeply lobed leaves and quick height ... but its stem is fairly smooth (although not woody, for otherwise its weirdly lobed leaves look akin to sassafras!) and its leaf width and veining is notable different ...

It has reappeared for five summers in different spots around the property ... it is very challenging to pull ... it grows well over waist-high ... I decided that I was just going to have to wait for a bloom (this IS how I keep getting in trouble, n.b. the unknown umbellifers listed above, whose one became fifty ...) but I could not stop searching ... So, with my mother’s aid, we scoured plant books, weed id services, websites, exploring possibilities of this mystery plant’s potential links with or being: |

Confirmed ... rambunctious squirrels bounding through the figs broke it in half in early September, but its response was to quickly send forth two long, yellowish flower spikes.

Confirmed ... rambunctious squirrels bounding through the figs broke it in half in early September, but its response was to quickly send forth two long, yellowish flower spikes.

- someone in the Nightshade family, the Atropa genus -- given, like Atropa belladonna, their immense possible heights, and their long-viable seeds, like this unknown plant's five summer repeat appearances all around the yard ... ??

- perhaps in the Malvaceae family -- like the Virginia mallow (Sida hermaphrodita) or the tall mallow (Malva sylvestris), given, again their over waist-height and their lobed leaves ... ??

- maybe in the Brassicaceae family, namely the Cardamine genus, the toothworts, who comprise couple hundred species -- some also bearing lobed leaves ... ??

Giant Ragweed (Ambrosia trifida): also called great ragweed, kinghead, crownweed, wild hemp, horseweed, bitterweed, tall ambrosia, buffalo weed ... so far, this is my best guess as to my mystery plant; from what I can see so far in its growth, its specs—two to ten inch leaves are opposite (although can be alternate at top of tall specimens) with deep three-to-five lobes, reaching up to six meters in fertile soil—seem to neatly match. While its being an annual threw me—I have had the plant for five years in the landscape, but have yet to see it flower—its seeds can remain viable in the soil for at least nine years, and I know my topsoil, brought in five years ago, was horribly root and chigger-full dredge from scrubby old crop and pasture fields, excatly where such a beast prefers to find itself. Giant ragweed, like its cousin common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia), is the major pollen contributor to early fall hay fever. If two to five inch greenish-yellow flower spikes appear soon, I will know for sure.*

* Richard Dickinson and France Royer, Weeds of North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 56-59.

36)

|

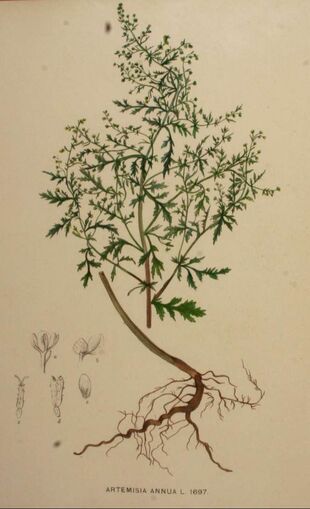

Sweet Annie (Artemisia annua)

So, it is not fair to call sweet annie a weed—according to a great online herb retailer, ‘The Grower’s Exchange,’ it’s “a wonderfully aromatic annual that will scent your whole yard with sweetness!”*—but it has made my inventory as an un-planted visitor who has volunteered itself sporadically over the last couple of summers in my fieldstone walk, yard, and garden beds. A ‘welcomed weed,’ perhaps, better expresses it; sweet annie is a delight, even when she appears in the most awkward of places. As the retailer’s quote and her common name suggest, sweet annie is remarkably sweet: her scent, her feathery, ferny, cut leaves that billow—especially notable when she reaches her full up to six foot height. Her form is fairly erect and branching, typically three to six feet tall in the garden, her light green stems staying fairly slender despite the heights she can reach. Her leaves are alternately spaced along her stems, some lower ones reaching up to six inches, those at her tips, rather petite; all are pinnately |

divided into narrow lanceolate lobes with the occasional cleft or tooth about their margins. Her late-summer floral panicles are narrow and under two inches in length, held on her upper stems, branching into racemes of tiny, drooping green-white-yellow flowerheads; each flower is barely two millimeters, and rather scentless, not needing to compete with the lush, rather fruity smell of her foliage. Her flower fruits into achenes of the tiniest seed that can drift off on the air, so to reproduce elsewhere and widely. While she prefers full sun and well-drained and fertile soil, her volunteers pop up in all manner of locations--i.e., she is only an annual, but a prolific self-seeder, sometimes rather miraculously appearing, even in dry gravel!, as she does here, for I have never planted her in this yard, but comes she does, again and again. Despite her steady appearance for me, however, she is not considered invasive, and only sometimes named as naturalized, with most instances of her escape from cultivation being short lived.**

As an artemisia, or wormwood, she is as easy and tough an annual as wispy soft and scented. This same delightful scent is also a fairly effective repulsive to garden pests, and proves to be a nice smelling repellant as a dried herb for sachets in drawers and closets. She also seems to appear frequently dried in homemade wreaths, crumpled for scattering as a carpet herb before vacuuming, and being hung in showers or steam rooms. Her pest repellant scent is matched by her bitter foliage, hence she suffers hardly any munching by mammal critters or beneficial insects, her flowers are petite and wind-pollinated, so do not really attract pollinators, and her seeds are so minute, birds seem uninterested. However, she is a rather famous herb for her human medicinal properties. (Any google search on her requires your digging at least several pages in to find an actual herbal guide rather than medical journal or holistic touts.) She was introduced to the U.S. from Eurasia as a medicinal herb, and has a long, 2,000 plus year history of uses, and frequent, current investigation into more. Her main indications have been for relieving pain and combatting fever; her most famous contribution is in helping to treat malaria. In 1970 the Chinese scientist Tu Youyou discovered her to have two compounds remarkably potent against the disease, which were then made into the artesunate drug chiefly used today, and for which he earned a partial Nobel Prize in Physiology/Medicine in 2015. The World Health Organization (WHO) acknowledges the efficacy of some sweet annie herbal remedies against malaria due to the presence of its chemical artemisinin (what the journals properly call ‘a lactone sesquiterpene endoperoxide’), although does not recommend its homemade use (which may be under-dosing patients, and could lead to malaria developing a resistance to the plant’s active chemical). Derivatives of this chemical in sweet annie has been investigated for treatment of COVID-19 (including an alternative therapy in drink form publicized by Madagascar’s president, and several more promising-in-the-lab tests by German and Danish scientists showing its anti-viral activity, as well as trials by the University of Kentucky with Mexico, tests by China, and tests of a different species in South Africa), but according to the WHO, initial various trials produced little to no effect and thus they say there is yet no evidence for its effectiveness. There are numerous other traditional usages of the herb, however, many of which have led to rigorous empirical testing of its biochemical composition leading to verified findings of its anti-hyperlipidemic and anti-cholesterolemic (agents for lowering cholesterol), anti-plasmodial (an agent against malarial-causing parasites), anti-convulsant (reductive of convulsions), anti-inflammatory (reductive of inflammation), and anti-microbial and anti-viral (against microbes and viruses) properties.***

As an artemisia, or wormwood, she is as easy and tough an annual as wispy soft and scented. This same delightful scent is also a fairly effective repulsive to garden pests, and proves to be a nice smelling repellant as a dried herb for sachets in drawers and closets. She also seems to appear frequently dried in homemade wreaths, crumpled for scattering as a carpet herb before vacuuming, and being hung in showers or steam rooms. Her pest repellant scent is matched by her bitter foliage, hence she suffers hardly any munching by mammal critters or beneficial insects, her flowers are petite and wind-pollinated, so do not really attract pollinators, and her seeds are so minute, birds seem uninterested. However, she is a rather famous herb for her human medicinal properties. (Any google search on her requires your digging at least several pages in to find an actual herbal guide rather than medical journal or holistic touts.) She was introduced to the U.S. from Eurasia as a medicinal herb, and has a long, 2,000 plus year history of uses, and frequent, current investigation into more. Her main indications have been for relieving pain and combatting fever; her most famous contribution is in helping to treat malaria. In 1970 the Chinese scientist Tu Youyou discovered her to have two compounds remarkably potent against the disease, which were then made into the artesunate drug chiefly used today, and for which he earned a partial Nobel Prize in Physiology/Medicine in 2015. The World Health Organization (WHO) acknowledges the efficacy of some sweet annie herbal remedies against malaria due to the presence of its chemical artemisinin (what the journals properly call ‘a lactone sesquiterpene endoperoxide’), although does not recommend its homemade use (which may be under-dosing patients, and could lead to malaria developing a resistance to the plant’s active chemical). Derivatives of this chemical in sweet annie has been investigated for treatment of COVID-19 (including an alternative therapy in drink form publicized by Madagascar’s president, and several more promising-in-the-lab tests by German and Danish scientists showing its anti-viral activity, as well as trials by the University of Kentucky with Mexico, tests by China, and tests of a different species in South Africa), but according to the WHO, initial various trials produced little to no effect and thus they say there is yet no evidence for its effectiveness. There are numerous other traditional usages of the herb, however, many of which have led to rigorous empirical testing of its biochemical composition leading to verified findings of its anti-hyperlipidemic and anti-cholesterolemic (agents for lowering cholesterol), anti-plasmodial (an agent against malarial-causing parasites), anti-convulsant (reductive of convulsions), anti-inflammatory (reductive of inflammation), and anti-microbial and anti-viral (against microbes and viruses) properties.***

While it is impressive how beneficial she has been and may prove to be in our medical investigations, my delight in her is more immediate: the direct sensual conflagration of soft, wispy touch, tinging bright scent, her remarkable color, her newest seedlings merging a baby spring green with glinting silver, her fascinating form that grows so tall but stays so nimble. She is a weed I don’t ever pull.

p.s., that is, perhaps, why the following summer a mighty, mighty towering Sweet Annie appeared in my first-season weed-and-wild-flower bed, which is about forty feet down slope from where the delicate little seedling appeared last year. It is early September and she is yet to bloom, but adds some wispy drama to the chaotic jumble of the bed, and I won't mind her re-appearance in years to come, though will temper the anticipated over proliferation of her seedlings.

* The Grower’s Exchange page, available ~~HERE~~.

** Cf., Illinois Wildflowers page, available ~~HERE~~; Gardening Know How page, available ~~HERE~~; Flora of North America database, available ~~HERE~~.

*** Cf., Mother Earth Living, available ~~HERE~~; World Health Organization, WHO Position Statement (June 2012), “Effectiveness of Non-Pharmaceutical Forms of Artemisia annua L. against malaria,” available ~~HERE~~; BBC News, “Coronavirus: What do we know about the artemisia plant?,” available ~~HERE~~; Axelle Septembre-Malaterre, et al, “Artemisia annua, a Traditional Plant Brought to Light,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, 14 (2020): 4986, available ~~HERE~~; University of Kentucky HealthCare news, available ~~HERE~~; WedMD page, available ~~HERE~~.

Herbal Illustration: Artemisia annua, Jan Kops (1765-1849), ed., Flora Batava (Haarlem: Vincent Loosjes, 1906, originally compiled in 1807), part 22, plate 1697, text and poorly reproduced illustrations available ~~HERE~~, specific plate nicely reproduced ~~HERE~~.

37)

|

Mulberry Weed (Fatoua villosa)

Classified in the Moraceae, or mulberry, family, your genus contains only three species, and yours is furthermore considered an oddity for being the family’s only herb, i.e., being neither a shrub nor tree. Beyond your family membership, your common name is due to your resemblance to a mulberry tree seeding, although you have also been dubbed the less attractive ‘hairy crabweed.’ You are also said to somewhat resemble false nettle (Boehmeria cylindrica) (which, too, likes moist shade, but has opposite leaves with more pointed, toothy margins) and starts of the Asteraceae family’s hairy galinsoga (Galinsoga spp., especially G. quafriradiata) (which also love to appear in container nurseries, but has hairier leaves and develops a petite white petaled and yellow-centered daisy-like flower), although I first took you to be a lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) seedling, as I have a prolific, less wrinkly variety that likes to pop up all over the yard (however, the lovely tea herb has mint’s characteristic square stems and more leaf veining). As an east Asian native, mulberry weed arrived in North |

America—especially the southeastern U.S.—in the latter half of the 1900’s—your first report was in Louisiana, variably cited as in the 1950’s or 1964, but thought to predate that—presumably by nursery stock contamination, by which you still frequently enter private gardens, although, as a voracious seeder, you can quickly free yourself from them to spread into surrounding grounds. On typically slender and typically short (but capable of up to two and a half feet tall), erect, and occasionally lightly branching and lightly hairy stems, your leaves are fresh spring green hearts or triangles with neatly petite scalloped margins (sometimes slightly more pointedly toothy) reaching out from half again as long petioles. Your inconspicuous individually white or light green flowers that collectively appear purple to brown can happen when your stature is still at seedling heights and form in under an inch diameter feathery clusters in your leaf axils. Your seeds are many, ripen quickly, occasionally display dehiscent behavior (exploding forth to sail nearly four feet away), and can germinate in a mere 30 days anytime from April to late November with your resultant seedlings producing their own new seeds within 12 days after hitting their two-leaf growth stage, thus each patch producing up to five generations in a season. Understandably, then, you are listed as an invasive in Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, and Virginia. You prefer moist, shady areas, and your seeds require light to germinate, hence can be controlled by heavy mulching or the quick removal of your seedlings that attempt mulch-top growing sites. It is recommended to pluck and dispose of seedlings as soon as spotted, since they may go to seed so young.*

* North Carolina Extension page, available ~~HERE~~; Invasive Plant Atlas, available ~~HERE~~; Native Plant Trust Go Botany page, available ~~HERE~~; B. W. Wells Association Rockcliff Farm page, available ~~HERE~~; and University of Florida IFAS Extension page, available ~~HERE~~.

** Tropical Plants Database, available ~~HERE~~ (which cites Plant Resources of South-East Asia (PROSEA) site, available ~~HERE~~); Bplant.org page, available ~~HERE~~.

38)

|

Red Mulberry Tree (Morus rubra)

Now, please do forgive me for saddling you with the name “weed,” for you are a native tree, a mighty one—your other common name, ‘moral’, perhaps heightening my guilt—but you did appear in my yard uninvited and, I dare say, in an unfortunate location. (I am flattered that, while you are a prolific self-seeder, you chose my yard, as you prefer rich, moist, well-drained soils in full sun -- were you elsewhere, I would leave you, care for you, share your fruits with all the birds and critters, watch you grow to your average 30-36-feet or up to 60-foot possible heights.) |

Your growth develops you into a two-foot diameter, rather short, coppery-brown trunked but broad, rounded, densely crowned tree; all parts of you have a milky sap with a low toxicity. Your deciduous, soft, lightly haired leaves are remarkably freestyle, toothy-margined, up to eight inches and roughly ovate to heart-shaped with elongated tips and with or without multiple, irregular lobes, which turn golden in autumn. Your springtime flowers hang in small, greenish cylindrical drupes. Your fragrant, edible-when-ripe fruits make you look like a blackberry vine willed itself into becoming a tree. They transition from unripe green through red to near-black, but are larger, more elongated than vined blackberries. These berries have long been used by Native Americans and people especially throughout Appalachia fresh or cooked into breads, pies and cakes, and preserves, dried for snacking or baking, pressed for beverages and fermented for wine. Medicinally, you have a history of aiding dysentery, and as a worming agent or a laxative and emetic. Your wood serves well outside or in, from fence posts to furniture; the fibrous inner bark of your shoots was woven into cloaks by the Choctaw people. You are the host for the larva of the Mourning Cloak (Nymphalis antiopa) and, possibly, for the Red Admiral (Vanessa atalanta), and feed all sorts of other butterflies, birds, especially catbirds and mocking birds, and critters, like squirrels, foxes, opossums, and raccoons.

A tree care person just confirmed your identity, but looked rather aghast I had yet to cut you down and dig you out. Instead of your chosen spot two inches from my driveway and four from a small stone wall and property line, I wonder if I could transplant you? Perhaps elsewhere, near, and you could grace me with some fruit and split the attention all the local birds and critters pay to devouring my figs … it might be worth the shot: a fall project.*

* Cf., Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center page, available ~~HERE~~; North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox page, available ~~HERE~~.

39)

Hackberry Tree (Celtis occidentalis):

While we are on the topic of trees … please do not misunderstand me: I am not calling you weeds per se, and mean no disrespect (I love my trees immensely) … but … when it comes to the spring, and then again in autumn, bonanzas of uninvited greenery pop forth in my garden beds, and the good percentage therein are hackberry (and some elm and oak, addressed next) saplings. I fully appreciate your desire to make my postage-stamp sized yard and beds into a forest—and there is compelling argument, environmentally, that I ought to let you—but besides the three large and two medium trees on my property, and dozen more surrounding me on all sides, I’d really like a little land to plant to (at least more of) my whim. So, let me explain my sighing complaints (beyond your excessive barrage of babies) and how I’ve come around to also praise you.

Admittedly, Celtis occidentalis, common hackberry, you did not immediately steal my heart. At first take, you were scruffy, wiry looking greyish towers, dangerously tall to be so thin, warty ridged, corky and lichen-covered, frequently dropping half-rotted branches; your little elm-like leaves are loved by aphid and scale, and they crisp early, barely even turning dull yellow, then fall like snow to show off their mass of nipple galls. But, living U-ringed by five massive trees, I came to better appreciate you. First, to ensure you wouldn’t poison my voracious pups, I investigated your fruit—drupes honestly mistakable for a nut, a little purplish thin skin wrapping a mini-marble-sized case that takes a bit of force to crack. Quite the opposite: birds are crazy for the nutritious fruits, from wild turkeys and quail, cedar waxwings, woodpeckers, and robins, as are deer and small mammals, and edible for humans, too, with perhaps the best, oddest, description on a forager site: “A wild tree fruit that eats like a nut loaded with carbohydrates, protein and fat, and tastes a bit sweet like squash with a hint of dates.”* You hackberries, as large native trees, are also fine supports for good bug-life—and this formed reason two for my eventual respect and straight-up fluttering summertime heart: you are the host for the

While we are on the topic of trees … please do not misunderstand me: I am not calling you weeds per se, and mean no disrespect (I love my trees immensely) … but … when it comes to the spring, and then again in autumn, bonanzas of uninvited greenery pop forth in my garden beds, and the good percentage therein are hackberry (and some elm and oak, addressed next) saplings. I fully appreciate your desire to make my postage-stamp sized yard and beds into a forest—and there is compelling argument, environmentally, that I ought to let you—but besides the three large and two medium trees on my property, and dozen more surrounding me on all sides, I’d really like a little land to plant to (at least more of) my whim. So, let me explain my sighing complaints (beyond your excessive barrage of babies) and how I’ve come around to also praise you.

Admittedly, Celtis occidentalis, common hackberry, you did not immediately steal my heart. At first take, you were scruffy, wiry looking greyish towers, dangerously tall to be so thin, warty ridged, corky and lichen-covered, frequently dropping half-rotted branches; your little elm-like leaves are loved by aphid and scale, and they crisp early, barely even turning dull yellow, then fall like snow to show off their mass of nipple galls. But, living U-ringed by five massive trees, I came to better appreciate you. First, to ensure you wouldn’t poison my voracious pups, I investigated your fruit—drupes honestly mistakable for a nut, a little purplish thin skin wrapping a mini-marble-sized case that takes a bit of force to crack. Quite the opposite: birds are crazy for the nutritious fruits, from wild turkeys and quail, cedar waxwings, woodpeckers, and robins, as are deer and small mammals, and edible for humans, too, with perhaps the best, oddest, description on a forager site: “A wild tree fruit that eats like a nut loaded with carbohydrates, protein and fat, and tastes a bit sweet like squash with a hint of dates.”* You hackberries, as large native trees, are also fine supports for good bug-life—and this formed reason two for my eventual respect and straight-up fluttering summertime heart: you are the host for the

|

phenomenal Hackberry Emperor (Asterocampa celtis) butterflies, who flit, skim, and swoop about in uniforms in my kind of style: tawny brown sveltely adorned with black wingtips, zigzags, and polka-dots, offset with creamy-white bright spots (wild and sleekly chic at once, pictured at right). Douglas Tallamy’s Bringing Nature Home further enlightened me that you host a number of other stunning butterflies’ caterpillars, notably Mourning Cloaks (Nymphalis antiopa), Snouts (Libytheana carinenta), and Tawny Emperors (Asterocampa clyton).**

Hackberries, despite staying more slender (usually one to two feet, or up to three) can grow to up to around 70’ feet tall, spreading about as wide on long, arching but upright branches, and while preferring moisture, they are tough, with a deep root system, thus can survive in many and less than fine areas and conditions. While its wood is not terribly useful for building or furniture, early colonists would use it for barrel hoops or occasional homestead flooring. Several resources mention widespread Native American use of hackberries for food, medicine, and rituals.*** |

* Cf., Forager Chef, available ~~HERE~~.

** Douglas W. Tallamy, Bringing Nature Home: How you can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants (Portland: Timber Press, 2009), 318-19. *** Cf., Nebraska Forest Service, available ~~HERE~~; Arbor Day Blog, available ~~HERE~~; Missouri Botanical Garden, available ~~HERE~~; Texas A&M Forest Service page on hackberry nipple galls, available ~~HERE~~; Sciencing page, available ~~HERE~~; Morton Arboretum, available ~~HERE~~; Your Leaf, available ~~HERE~~. Image above: Nipple galls on leaves and marble-sized dried & cracked hackberry stone. Image right: one of innumerable seedling volunteers. |

40)

|

Elm (Ulmus, maybe American elm, U. americana, or Siberian U. pumila):

Given the devastation Dutch Elm disease wrought on you, I stutter ever calling you a weed, but, in my defense, you do appear in numbers terribly shocking given the one single arm of the one single momma tree that arches over my back fence, and from which I presume you all come, all spring through all fall. With arguably seven or eight native North American species (of which five can be found around Nashville) and around 35 altogether, plus a number of cross-bred varieties, identification of the miniature grove beyond my tall, back fence proved a challenge. From my imposed distance, I can tell that your bark is dark greyish-brown, deeply furrowed, your several inch long leaves are jaggedly toothed and pointed ovals, bright to dark green and turning gold and falling now in late autumn, but last spring I remember your nearly round papery seed cases. This description rules out very few species; your squeezed-in siting obscures your natural height and canopy shape; you bloomed in spring, so that rules our your being an endemic September elm (U. serotina); I see no ‘wings’ on your branches, suggesting you are neither a native rock elm (U. thomasii) nor a native winged elm (U. alata); per your bark, I presume you are neither a Chinese/lacebark (U. parvifolia) nor Japanese (Zelkova serrata) elm, as their bark is flatter, the former flaking to orange patches, the latter much smoother, nor a cherry-bark elm (U. villosa), as your bark looks nothing like a cherry’s, and I am uncertain about but disinclined to red/slippery elm (U. rubra), as pictures suggest their bark is a bit more flaking; and per your leaves, I suspect you are not a cedar elm (U. crassifolia), for your leaves are more pointed. I paused over the description of the Siberian elm (U. pumila) for its shorter mature heights (50-70’), desire for moist, well-drained soil (as you are growing alongside a stream/drainage canal), your tendency to weak branches (as you drop a lot over my fence), and aggressive nature (given the number of saplings I have around)—but remain wholly uncertain. I paused, too, perhaps hopefully, over the American elm (U. americana), which is also inclined to wetter sites, and especially shows your sort of deep, diamond-shaped bark furrows, and similar looking leaves.* Ultimately, I haven’t any certainty who you might be beyond being an elm. |

The futile search to identify you, however, has greatly increased my appreciation for elms. Douglas Tallamy registers the sad irony of how our sorrow at losing so many elms to Dutch elm disease led to a worse sorrow at then importing so many Asian elms, which do not support the wildlife our native trees did, and were probably the way the disease first arrived anyway.** Native species, on the other hand, support a number of butterflies and moths—notably mourning cloaks and question mark butterflies, and imperial, polyphemus, banded and white-marked tussocks, and yellow-necked caterpillar moths—including some who are strictly elm specialists, like the master of blending-in, the double-toothed prominent (Nerice bidentata), whose caterpillar back appears just like the jagged teeth of elm leaves, hence mimicking the leaf as perfect and whole (and thus he as not mere bird food) while he nibbles his way to his metamorphosis stage.***

Perhaps if I permit a few of your saplings to grow up, I can watch for any caterpillar activity, and perhaps will then know at least if your species is native or not. |

* Cf., Leafy Place page differentiating species of elm, available ~~HERE~~; Vanderbilt’s page on the September elm, available ~~HERE~~; The Morton Arboretum Siberian elm page, available ~~HERE~~, and on the American elm, available ~~HERE~~; USDA publication on Rock elm, available ~~HERE~~; Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center page on winged elm, available ~~HERE~~; Nashville Tree Conservation Corps American elm page, available ~~HERE~~; North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox page on American elm, available ~~HERE~~, and on Red/Slippery elm, available ~~HERE~~.

** Douglas W. Tallamy, Bringing Nature Home: How you can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants (Portland: Timber Press, 2009), 174.

*** Ibid., 174-75, 317-27.

41)

White and Southern Red Oaks (Quercus alba and Quercus falcata):

You have volunteered about my property, but you, no, I cannot call you weeds: your appearances only number in a handful; you are wanted here (even if not exactly where you have appeared); and ‘weedy,’ despite the health and heights of some (looking at you, giant ragweed), typically implies one “noticeably lean and scrawny,” and while you are now scraggly and barely knee-high, your average maturities find you capable of towering from 50 to over 100 feet tall*--so, really, you just made the weed list by fact of your surprising appearances and so I may sing your praises.

You have volunteered about my property, but you, no, I cannot call you weeds: your appearances only number in a handful; you are wanted here (even if not exactly where you have appeared); and ‘weedy,’ despite the health and heights of some (looking at you, giant ragweed), typically implies one “noticeably lean and scrawny,” and while you are now scraggly and barely knee-high, your average maturities find you capable of towering from 50 to over 100 feet tall*--so, really, you just made the weed list by fact of your surprising appearances and so I may sing your praises.