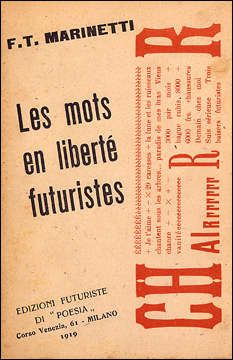

Futurism: Largely an Italian movement in the early 20th c., Futurism, as the name suggests, embraced content, styles, methods, and theories connected to contemporary, future-looking life. Specifically, this involved a glorification of technology, speed, the new, cars, aeroplanes, industrialized cities in diverse mediums, first in literature and then including everything from painting to all forms of design, music to architecture to sculpture, film to theatre. Its birth announcement was F. T. Marinetti’s “Le Futurisme,” published in the famous Parisian newspaper Le Figaro, and served as a rejection of the past and call to revolutionize the now, to forget about Italy’s cultural tradition and to embrace the radical modernism embodied in speed and machines. We will read two Futurist Manifestos, from F. T. Marinetti and Umberto Boccioni; other names associated with the movement include Giacomo Balla, Carlo Carrà, Bruno Munari, Luigi Russolo, Antonio Sant-Elia, and Gino Severini. Within painting and sculpture, futurism diversely used elements of cubist design (which they foreshadowed) and techniques to show movement.

More about Futurism:

- Wikipedia Article on Futurism <~here~>

- The Art Story on Futurism <~here~>

- Tate on Futurism <~here~>

- Artland on Futurism <~here~>

- National Galleries Scotland on Futurism <~here~>

- Smithsonian Article on Futurism <~here~>

- Wikipedia article on F.T. Marinetti <~here~>

- Wikipedia article on Umberto Boccioni <~here~>

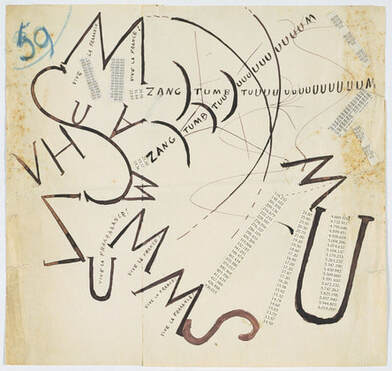

F. T. Marinetti’s “Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto,” pp.656-60

F. T. Marinetti (1876-1944)

F. T. Marinetti (1876-1944)

Marinetti’s manifesto spastically flits through ideas and claims, and yet does so with beautifully poetic language—a feature we will see in all the manifestos, an impassioned voice of the wholly committed adherents. A few key ideas to hold on to:

“Our growing need of truth is no longer satisfied with Form and Color as they have been understood hitherto” (656).

“The gesture which we would reproduce on canvas shall no longer be a fixed moment in universal dynamism. It shall simply be the dynamic sensation itself (made eternal)” (657).

And: “Space no longer exists …” (657).

“To paint a human figure you must not paint it; you must render the whole of its surrounding atmosphere” (657).

“Our growing need of truth is no longer satisfied with Form and Color as they have been understood hitherto” (656).

- This is the first of many rejections the manifesto expresses—here, take “Form and Color” to generally represent the traditional means of art (as they later reject “harmony”/“good taste,” as well as all once-used subjects, esp. nudes. Note the implicit claim that the tradition has clouded over, veiled, or hidden the “truth” that they want to now lay bare and express.

“The gesture which we would reproduce on canvas shall no longer be a fixed moment in universal dynamism. It shall simply be the dynamic sensation itself (made eternal)” (657).

And: “Space no longer exists …” (657).

- Here, we see the first two of many quotes emphasizing the movement’s embrace of dynamic motion, of speed, of movement. Presumably “space” is to be taken as the static scene abstracted from the dynamic flow of life.

“To paint a human figure you must not paint it; you must render the whole of its surrounding atmosphere” (657).

- This is a fascinating quote that builds from the previous two about emphasizing movement; here, the movement we see to be the full, pregnant atmosphere of one’s subject. Given the rest of the manifesto, we can assume this atmosphere to be dynamic and full of sensation, well beyond the actual things therein.

“Who can still believe in the opacity of bodies, since our sharpened and multiplied sensitiveness has already penetrated the obscure manifestations of the medium? Why should we forget in our creations the doubled power of our sight capable of giving results analogous to those of the X-rays?” (657).

- Here, we see one example of technological development (X-rays) influencing their views on art. (Cf., Benjamin’s essay when he discusses the birth of photography and film.)

“The construction of pictures has hitherto been foolishly traditional. Painters have shown us the objects and people placed before us. We shall henceforward put the spectator in the center of the picture” (657).

- This dramatic claim reveals something that we see very intimately in our media today—think, for example, of developments in film (the hand-held cameras’ jerky movements that make you feel that you are a part of the action) and sound reproduction (stereo sound, quadrophonic sound, and then surround sound systems). If art is prized as an experience over being a mere object or possession, consider the affect of using techniques to dynamically engage the viewer even further into the art performance.

- Cf., Foucault <~here~> for how Veláquez's Las Meninas' draws in the viewer

“We would at any price re-enter into life” (657).

- Again, we see an emphasis on the awakening, throwing off the veils or sleep that has kept us from the truth and depth of experience.

“Our renovated consciousness does not permit us to look upon man as the center of universal life. The suffering of man is of the same interest to us as the suffering of an electric lamp, which, with spasmodic starts, shrieks out the most heart-rendering expressions of color” (658).

- This is a fascinating development in the essay—the three pieces from critical theory before this have cast a somewhat wary eye to technological developments as further divorcing us from true reality and especially nature. Here, while they do not spell out the theoretical justification for it, we see the Italian Futurists rejecting technology as something by which humanity dominates nature, and instead as something that puts humanity in its place amongst things of nature.

- Cf., Kandinsky <~here~> for his color theory and 'associations' (synesthesia)

“In order to conceive and understand the novel beauties of a Futurist picture, the soul must be purified (become again pure); the eye must be freed from its veil of atavism and culture, so that it may at last look upon Nature and not upon the museum as the one and only standard” (658).

- While the language of “purity” and “souls” seems a little discordant with this intense embrace of a gritty, fast, young, violent, industrialized future, we again see the idea of how we must free ourselves from the veils of tradition.

“How is it possible to still see the human face pink, now that our life, redoubled by noctambulism, has multiplied our perceptions as colorists?” (658).

- Like with the X-rays earlier, we see the broadening of perspective born from technical developments here. (Noctambulism being “sleep-walking.”)

“The time has passed for our sensations in painting to be whispered. We wish them in the future to sing and re-echo upon our canvases in deafening and triumphant flourishes” (658).

- Again, dramatic language that champions the vibrant and dynamic.

“Our art will probably be accused of tormented and decadent cerebralism. But we shall merely answer that we are, on the contrary, the primitives of a new sensitiveness, multiplied hundredfold, and that our art is intoxicated with spontaneity and power” (658).

- This is an interesting quote because the vehement and bombastic language and claims are hardly what we would categorize as very cerebral (instead, we would think this of a highly conceptual, theory driven art), but, presumably the idea is that they will be accused of letting a dramatic theory lead their art creation. The response being that they are the new “primitives,” presumably those who see and feel things more raw and true than the tradition.

Ugo Giannattasio, "Untitled," 1920

Ugo Giannattasio, "Untitled," 1920

Their Declarations (in essence):

- (1) no imitation; all originality;

- (2) reject “harmony” and “good taste” as ill suited terms;

- (3) art critics are useless and harmful;

- (4) all previous subjects rejected; replaced with those to express speed, etc.;

- (5) “madman” is a title of honor;

- (6) “innate complementariness” is necessary;

- (7) universal dynamism must be expressed as dynamic sensation;

- (8) Nature must be rendered sincerely and purely;

- (9) movement and light destroy the materiality of bodies.

Their Rejections (in essence):

- (1) no patina of time;

- (2) no archaic flatness;

- (3) no support of the secessionists and independents;

- (4) no nudes.

They end upon the clarification of the last rejection—no nudes: this is not due to viewing them as immoral, but just as having become monotonous; hence, they command the suppression of all nudes in painting for ten years.

|

“ ... our art is intoxicated with spontaneity

and power ...” (F. T. Marinetti, 658) |

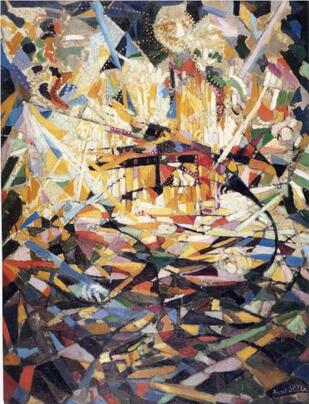

Umberto Boccioni’s “Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture,” pp.661-66;

Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916)

Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916)

Boccioni, like Marinetti, is writing his manifesto from within the school of Futurism; many of the principles that the latter proposes are taken up and applied to sculpture by Boccioni.

The first real similarity is the rejection of traditional principles, methods, and subjects: “sculpture offers a spectacle of such barbarism, clumsiness, and monotonous imitation, that my Futurist eye recoils from it with profound disgust!” (661). Like Marinetti, Boccioni rejects imitation in favor of new creative originality, rejects an adherence to past models, and rejects especially the limitation of only carving new old-looking nudes (“the artist copies the nude and studies classical statuary with the simpleminded conviction that he can find a style corresponding to modern sensibility without relinquishing the traditional concept of sculptural form” (661-2)).

Boccioni berates his contemporary sculptors for not innovating, like the work he sees in painting and poetry (“Sculptors must convince themselves of this absolute truth: to continue to construct and want to create with Egyptian, Greek, or Michelangelesque elements, is like wanting to draw water from a dry well with a bottomless bucket” (662)).

The first real similarity is the rejection of traditional principles, methods, and subjects: “sculpture offers a spectacle of such barbarism, clumsiness, and monotonous imitation, that my Futurist eye recoils from it with profound disgust!” (661). Like Marinetti, Boccioni rejects imitation in favor of new creative originality, rejects an adherence to past models, and rejects especially the limitation of only carving new old-looking nudes (“the artist copies the nude and studies classical statuary with the simpleminded conviction that he can find a style corresponding to modern sensibility without relinquishing the traditional concept of sculptural form” (661-2)).

Boccioni berates his contemporary sculptors for not innovating, like the work he sees in painting and poetry (“Sculptors must convince themselves of this absolute truth: to continue to construct and want to create with Egyptian, Greek, or Michelangelesque elements, is like wanting to draw water from a dry well with a bottomless bucket” (662)).

|

“There can be no renewal in art whatever if the essence itself is not renewed, that is, the vision and concept of line and masses that form the arabesque” (662). Thus, he not proposing simply new subjects or materials, but a radical reinterpretation of the theory animating sculpture (and then new subjects, new materials, new forms, new lines, new colors, and new rhythm). Sculpture cannot, he declares, be contemporary just by representing contemporary things, any exterior aspects of contemporary life; instead, it must wholly remake itself from its essence out. |

He then introduces the first of three new futurist concepts to guide this new sculpture:

Interpretation of Planes: a plane will be any surface, any spread of space rendered as representational of a thing; the interpretation of these planes will be the relationships and interactions between things. He sees this development in Futurist painting’s “study of landscape and the environment, which are made to react simultaneously in relationship to the human figures or objects …” (662). This is a theoretically rich idea—it is a rethinking of subject-object relationships.

Interpretation of Planes: a plane will be any surface, any spread of space rendered as representational of a thing; the interpretation of these planes will be the relationships and interactions between things. He sees this development in Futurist painting’s “study of landscape and the environment, which are made to react simultaneously in relationship to the human figures or objects …” (662). This is a theoretically rich idea—it is a rethinking of subject-object relationships.

|

Apparent Plastic Infinite and Internal Plastic Infinite: (“plastic,” from the Greek plassein, “to mold,” is that which is moldable, what offers a scope for creativity; those arts differentiated from the literary and musical, that which is made of something.) What exactly Boccioni means here is vague, but we can get a sense of it by quoting the full context in which these terms appear:

“We have to start from the central nucleus of the object that we want to create, in order to discover the new laws, that is, the new forms, that link it invisibly but mathematically to the apparent plastic infinite and to the internal plastic infinite. The new plastic art will, then, be a translation into plaster, bronze, glass, wood, and any other material, of those atmospheric planes that link and intersect things” (662).

The apparent and internal plastic infinites, presumably the given/presented possibilities and the essential/inner possibilities for the molded thing, guide and/or frame the creation of the thing-created; these infinite possibilities are the linkages/intersections that are formative of the atmospheric whole or totality of the sculptural work (the plastic work).

Physical Transcendentalism: The above quote is the expression of what he calls physical transcendentalism—presumably, the plastic work, the sculpture, is something and embodies the transcendence of the static to embrace the atmospheric linkage or intersection of planes.

Boccioni then moves to two attempts that have been made in contemporary sculpture to capture modernity and four sculptors that come close to or miss the mark to which he wants sculpture to go.

The attempts:

- (1) The Decorative: this attempt focuses on style; it is “anonymous and disordered,” it lacks proper coordination because it is too limited by the building it is to decorate.

- (2) The Strictly Plastic: this attempt focuses on material; it is “too isolated and fragmentary,” it lacks an idea that could synthesize its elements and provide it a guiding principle.

The Sculptors:

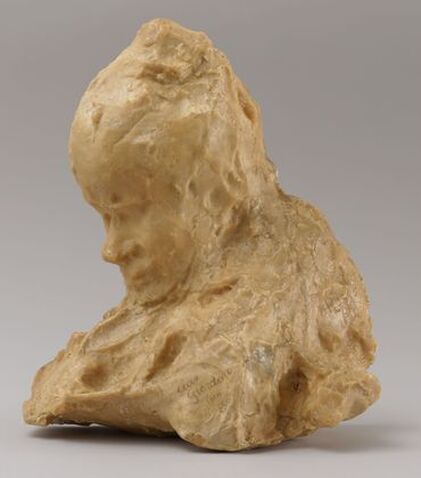

- Medardo Rosso (1858-1928; Italian sculptor expelled from art studies for his protest vs. traditional teaching methods, involved in artistic avant-garde, he broke from traditional styles to capture a naturalism in contemporary subjects some exceedingly realistically reproduced and some very abstract, but all are full of emotional involvement)—for Boccioni, he who comes closest to the Futurist aim; he is modern and revolutionary, but too limited by still representing the human figure as something in-itself (not linked and atmospheric enough), thus, still too traditional and episodic (static, detached from pure dynamism).

- For the Museo Medardo Rosso: <~here~>

- Constantin Meunier (1831-1905; Belgium sculptor and painter who worked with modernist subject matter, especially the rural peasants and the city poor, but through both traditional and religious styles despite being closely involved with the European avant-garde realist artists in Brussels)—for Boccioni, he who has “contributed nothing new to sculptural sensibility” (663) (i.e., too beholden to the ancient Greek tradition).

- For the Musée Meunier: <~here~>

- Antoine Bourdelle (1861-1929; French sculptor, started as assistant to Rodin, respected him, despite contrasting style; Bourdelle embraced plane-construction, simplifying his lines; his subjects were mainly from Greek mythology and Roman sculpture)—for Boccioni, he who “brings to the sculptural block an almost fanatic severity of abstract architectural masses” (663) (i.e., too beholden to the Gothic tradition).

- For the Musée Bourdelle: <~here~>

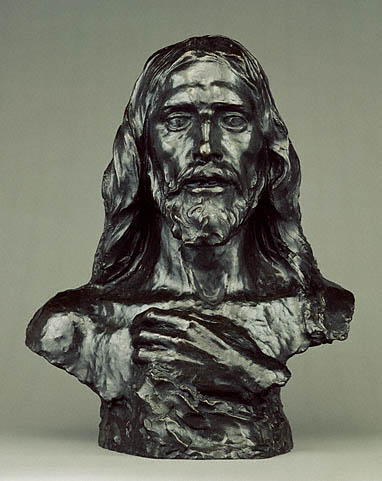

- Auguste Rodin (1840-1917; French sculptor famed for “The Thinker,” considered father of modern sculpture by everyone besides the Futurists; his works were shocking, criticized for their breaking from the decorative tradition and his embrace of the realism of the individual body, showing its difference from ideal types)—for Boccioni, he of “vaster spiritual agility,” would be “truly modern” if he was not beholden to the qualities already possessed by Michelangelo and Donatello (i.e., too beholden to Italian Renaissance).

- For the Musée Rodin, <~here~>

So, while Rosso comes the closest to what Boccioni is advocating for Futurist sculpture, he does not go far enough. What he (and all sculptors) needs to do is search for the “Style of the Movement,” “that is, by making systematic and definitive in a synthesis what Impressionism has given us as fragmentary, accidental, and thus analytical. And this systematization of the vibrations of sculpture, whose foundation will be architectural, not only in the construction of the masses, but in such a way that the block of the sculpture will contain within itself the architectural elements of the sculptural environment in which the subject lives” (664).

- For more on Impressionism, via The Met: <~here~>

The result will show the total environment, the atmosphere, of the subject; it will be mathematical and geometrical, it will reinvent harmony and redesign form. “Traditionally a statue is carved out or delineated against the atmospheric environment in which it is exhibited. Futurist painting has overcome this conception of the rhythmic continuity of the lines in a human figure and of the figure’s isolation from its background and its invisible involving space” (664). Thus, Boccioni calls us to get rid of definite lines and closed sculpture, to break open figures, to enclose sculpture in environment, to let the whole world fall in on and merge with us, to have harmony match infinite creative imagination, to not imitate tradition, to use transparent planes, to innovate intuitive coloration, to make static lines dynamic and forceful, to use the straight line in an alive and palpitating way, to capture infinite expression of the material, to lay bare fundamental severity of modern machinery, and to, thus, achieve reality by going beyond the bounds of art (664-5).

He ends his manifesto with nine conclusions (in essence):

- (1) base sculpture on abstract reconstruction of planes;

- (2) get rid of traditional sublimity of the subject;

- (3) get rid of realist, episodic construction (so as to perceive bodies and parts as plastic zones);

- (4) destroy the tradition of marble and bronze; embrace many, multiple materials;

- (5) replace musculature with intersections of planes;

- (6) choose new, modern subjects;

- (7) use the straight line;

- (8) create a sculpture of environment;

- (9) view your sculpture as the bridge between exterior (apparent) and interior plastic infinites.

Selection of Boccioni's Sculptures:

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by MacHighway