Søren Aabye Kierkegaard’s

Fear and Trembling: Dialectical Lyric by Johannes de silentio

* * * * * * * * * * * * *C O N T E N T S :

(1) Who is Søren Aabye Kierkegaard? (2) Who is Johannes de silentio? (3) What is Fear and Trembling: Dialectical Lyric? (4) Fear & Trembling Outline / Overview (5) Fear & Trembling Textual Analysis (6) Straying Thoughts Concluding K.'s F&T * * * * * * * * * * * * * |

Translations & Page Numbers currently from: Søren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling, tr. Alastair Hannay (New York: Penguin, 1986), isbn: 978-0140444490. Will be updated soon to include translations and pagination for: Søren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling/Repetition: Kierkegaard’s Writings, Vol. 6, trs. Howard & Edna Hong (Princeton: Princeton U.P., 1983), isbn: 978-0691020266. |

(1) Who is Søren Aabye Kierkegaard? He was a Danish philosopher and theologian (as well as a writer contributing to psychology and literary criticism and is considered one of the forbearers of existentialism (~~here~~)), born in 1813 and died in 1855; he lived his whole life in Copenhagen, Denmark, travelling from the country only five times (to Berlin and to Sweden). He published nearly 40 works in his lifetime, leaving hundreds upon hundreds of pages unpublished at his death; he is certainly one of the most prolific writers in philosophy.

He was raised in an odd, but very wealthy family (his mother, he never mentions, although we know she became pregnant with the young Kierkegaard before wedlock; his father was a melancholic ridden with pious guilt and a very sharp intellect and imagination; of his six siblings, all but two died before reaching 34, which the father had predicted would be the death of them all, hearkening the age of Jesus at his crucifixion). The young Kierkegaard was a frail and rather eccentric child, yet very highly educated and cultured. He studied philosophy and theology at the Copenhagen University in a time when Denmark, like most of Europe, was dominated by Hegelian thought. A final, momentous life event to be noted was Kierkegaard’s engagement to and subsequent break of engagement to Regine Olsen—Kierkegaard’s writings are replete with the idea of the muse, the woman who inspires in the writer the conversion of sexual libido into poetic and philosophic production. But, he broke his engagement off, with the ensuing remorse suffering him his whole life, in favor of the monastic devotion to his work.

We will see his sophisticated critique of Hegel as we work through this text, but one point is worth mentioning right now: one of his main problems with Hegel was his evaluation that his philosophy was too divorced from everyday life; instead, he uphold the Greek ideal that one’s philosophy ought to be judged by the quality of the life of that philosopher, which he reinforced with a Christian ideal that one’s philosophy forms who one is, and it is for the whole of one’s self that God can eternally damn or reward. We can see in this critique the existentialist creed that makes one’s meaning and value by and through the choices and actions one undertakes in life. Thus, in his own work, Kierkegaard strives to erase abstractions and bear down on lived experience. We should not be mistaken, however, and think that his shunning of abstraction means that anything is going to be concrete in the sense of “clear” or “straightforward!” Instead, Kierkegaard’s abiding interest in literature, as well as philosophy, undertaking his own creative and critical writing, plays a role in making his thought ‘lived’ and yet indirect. We see the aesthetic fighting against and integrally fused with the philosophic in Fear and Trembling. We can also see how very personal this work is, and how very much it reflects its author—or, better, its authors …

(Image: Mike Newton, 'Soren Kierkegaard', 2017, oil on canvas; see ~here~).

{ ... { ... * ... } ... } { ... { ... * ... } ... } { ... { ... * ... } ... } { ... { ... * ... } ... } { ... { ... * ... } ... }

Additional Biographic Information and Philosophical Overviews:

{*} Storm’s Commentary & Bibliography {*}

{*} Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Overview {*}

{*} Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Overview {*}

{*} The Søren Kierkegaard Forskningscenteret {Research Center} {*}

{*} The Hong & Hong Kierkegaard Library {*}

{*} Kierkegaardiana {*}

{ ... { ... * ... } ... } { ... { ... * ... } ... } { ... { ... * ... } ... } { ... { ... * ... } ... } { ... { ... * ... } ... }

(2) Who is Johannes de silentio? The pseudonym. (See ~~here~~ for P. L. Møller's critical article in The Corsair on his pseudonyms.) Johannes de silentio (Johannes of silence, or the silent Johannes, or Silent John) is the pseudonym Kierkegaard assumes to write Fear and Trembling; the name is thought to be borrowed from a Grimm’s fairy tale, “The Faithful Servant” (aka “Faithful Johannes” ... (read it ~~here~~)), which entails a king required to behead his dearest children to save to his faithful servant Johannes. Thus ... silence is thus our author; yet, to be an author one cannot be silent. But, in a way, Johannes is silent—he is silent about faith: if you have it, you will not be able to explain it to anyone else. What we take from this work is that faith has no place in a system (i.e. Kierkegaard’s critique of G. W. F. Hegel’s philosophy). For Kierkegaard/Johannes: “Faith begins precisely where thinking leaves off” (10-11; 82).

(2) Who is Johannes de silentio? The pseudonym. (See ~~here~~ for P. L. Møller's critical article in The Corsair on his pseudonyms.) Johannes de silentio (Johannes of silence, or the silent Johannes, or Silent John) is the pseudonym Kierkegaard assumes to write Fear and Trembling; the name is thought to be borrowed from a Grimm’s fairy tale, “The Faithful Servant” (aka “Faithful Johannes” ... (read it ~~here~~)), which entails a king required to behead his dearest children to save to his faithful servant Johannes. Thus ... silence is thus our author; yet, to be an author one cannot be silent. But, in a way, Johannes is silent—he is silent about faith: if you have it, you will not be able to explain it to anyone else. What we take from this work is that faith has no place in a system (i.e. Kierkegaard’s critique of G. W. F. Hegel’s philosophy). For Kierkegaard/Johannes: “Faith begins precisely where thinking leaves off” (10-11; 82).

(3) What is Fear and Trembling: Dialectical Lyric? Well, it is a work about faith; but not in any sense that will be familiar, rather it will be about a faith that is and causes “fear” and “trembling.”

First, consider the title: Fear and Trembling :

The conjunction of the two words is poignant—it establishes a mood as well as proffering descriptives for the work’s concern: faith. The phrase is well represented Biblically, as the following, non-exhaustively, shows:

Now, let us look at the subtitle: “Dialectical Lyric:”

It is a work that is both lyrical, in part one (“Fear and Trembling:” Preface, Attunement, and Speech in Praise of Abraham), and dialectical, in the second part (“Problemata:” Preamble from the Heart, Problema I, II, III, and Epilogue). The “lyrical” part of the work can be understood as a poetic or literary rendering—it is aesthetic and is an aesthetic. The “dialectical” part can be understood as an art or method of philosophic activity: investigating (metaphysical) knowledge or truth claims by a means of diagnosing and addressing argumentative contradictions. Dialectics can be understood as the Platonic method of elenchos, the back and forth method of questionings wherein steps forward are made by revealing the flawed premises of proposed theses or the Hegelian method of discerning and working through the spiraling thesis, antithesis, and synthesis of premises. Kierkegaard’s dialectics, here, however, are precisely a challenge to Hegel’s dialectic conducted through his method and style.

Yet, we can understand these two conceptions ever further, as both are loaded concepts for Kierkegaard: The “dialectical lyric” and aesthetics … towards the religious:

Kierkegaard’s work can be seen as a dialectic from the first stage of the aesthetic, the second of the ethical, and the third as the religious. However, it is utterly crucial to remember that in a dialectic, the antithesis does not replace the thesis, nor does the synthesis obliterate the first two premises. Thus, the aesthetic is never done away with in favor of ethics or the religious.

Aesthetic life is identified as immediacy—unreflective knowledge—an immersion in the sensuousness of experience wherein one flees boredom by valorizing the possible, the potential, by a self-forcing and self-led fragmentation of the self, of the coherent subject of experience.

In Kierkegaard’s Concluding Unscientific Postscript, the person dedicated to the life of immediacy is “absolutely committed to relative ends”—this contradiction is rather like faith (also, references echo here as to how Hegel includes faith in unreflective knowledge) (9). In his Either/Or, the aesthete is pictured as Don Juan and Faust characters.

The ethical stage (Sittlichkeit in Hegel; the customs, societal, ethical norms) reveals the egoism of the aesthete as empty, as an escapist fancy, who despairs responsibility to the whole (community, the “universal”—in the sense of the specific ‘universe’ of the socially codified mores). It is a concretion of the abstract flights of the aesthetic. (We will see the necessary “suspension” of “ethics” in Fear and Trembling, which shows that Kierkegaard is holding out there being a power higher than that which establishes these social norms.)

The religious stage preserves the aesthetic force by the sense of possibility made infinite through the imagination. Here, though, because of the force of the ethical, the actual is as present as the potential. However, there is a very live question as to whether Kierkegaard (or anyone?) ever reaches the religious stage—instead, don’t we ever only reach the representation of the religious? Aren’t thought & language ideal? How, through the ideal, can one ever reach the actual?

Religion, for Kierkegaard, is not a matter of doctrine, dogma, or ritual; instead, it is a matter of passion, of individual, subjective passionate turning to the divine and beyond the human, beyond clerical mediation, beyond constructions or buildings or altars. It is only through faith that the individual has a chance to have true meaning; the illogical, anti-ethical, and inexpressible necessitates the self to make the self have value through choice—we choose eternity thereby choosing ourselves. This is a matter of electric freedom and paralyzing dread. It is only by the absurd that we have faith.

To praise Abraham as the “Father of Faith,” we ought to experience what he experienced (13). Thus, in the start of Fear and Trembling, the four versions of the Abraham story are used lyrically by Johannes, to point us to the dialectical in the sense that they render Abraham intelligible, but, becoming intelligible, these retellings do not show him to be the Father of Faith (12).

After the lyrical presentation, there is an attempt to experience these as thought: the dialectical investigation seen in the problemata. Thus, the dialectical part will be the exploration (but without synthesis) of this contradiction, which is one of ETHICS:

First, consider the title: Fear and Trembling :

The conjunction of the two words is poignant—it establishes a mood as well as proffering descriptives for the work’s concern: faith. The phrase is well represented Biblically, as the following, non-exhaustively, shows:

- “… fear and trembling seized me and made all my bones shake” (Job 4:14, NIV).

- “Fear and trembling have beset me; horror has overwhelmed me” (Psalm 55:5).

- “And his affection for you is all the greater when he remembers that you were all obedient, receiving him with fear and trembling” (2 Corinthians 7:15).

- “Slaves, obey your earthly masters with fear and trembling, with a sincere heart, as you would Christ …” (Ephesians 6:5, Eng Standard)

- “Therefore, my dear friends, as you have always obeyed--not only in my presence, but now much more in my absence--continue to work out your salvation with fear and trembling” (Philippians, 2:12).

- “The sight was so terrifying that Moses said, ‘I am trembling with fear’ (Hebrews 12:21).

- “Then the woman, knowing what had happened to her, came and fell at his feet and, trembling with fear, told him the whole truth” (Mark 5:33).

- “I came to you in weakness and fear, and with much trembling (1 Corinthians 2:3).

- “Serve the LORD with fear and rejoice with trembling (Psalm 2:11).

- “They will lick dust like a snake, like creatures that crawl on the ground. They will come trembling out of their dens; they will turn in fear to the LORD our God and will be afraid of you” (Micah 7:17).

- “For thus saith the LORD; We have heard a voice of trembling, of fear, and not of peace” (Jeremiah 30:5, KJV).

- “Son of man, tremble as you eat your food, and shudder in fear as you drink your water” (Ezekiel 12:18).

Now, let us look at the subtitle: “Dialectical Lyric:”

It is a work that is both lyrical, in part one (“Fear and Trembling:” Preface, Attunement, and Speech in Praise of Abraham), and dialectical, in the second part (“Problemata:” Preamble from the Heart, Problema I, II, III, and Epilogue). The “lyrical” part of the work can be understood as a poetic or literary rendering—it is aesthetic and is an aesthetic. The “dialectical” part can be understood as an art or method of philosophic activity: investigating (metaphysical) knowledge or truth claims by a means of diagnosing and addressing argumentative contradictions. Dialectics can be understood as the Platonic method of elenchos, the back and forth method of questionings wherein steps forward are made by revealing the flawed premises of proposed theses or the Hegelian method of discerning and working through the spiraling thesis, antithesis, and synthesis of premises. Kierkegaard’s dialectics, here, however, are precisely a challenge to Hegel’s dialectic conducted through his method and style.

Yet, we can understand these two conceptions ever further, as both are loaded concepts for Kierkegaard: The “dialectical lyric” and aesthetics … towards the religious:

Kierkegaard’s work can be seen as a dialectic from the first stage of the aesthetic, the second of the ethical, and the third as the religious. However, it is utterly crucial to remember that in a dialectic, the antithesis does not replace the thesis, nor does the synthesis obliterate the first two premises. Thus, the aesthetic is never done away with in favor of ethics or the religious.

- Aesthetics: “… it is … to treat life itself as a repository of objects of longing or loathing, as well as degrees of lesser affect in between, in short as a pool of goods (of whatever kind) to be secured and the lack of them avoided” (Alastair Hannay, Introduction, 9).

Aesthetic life is identified as immediacy—unreflective knowledge—an immersion in the sensuousness of experience wherein one flees boredom by valorizing the possible, the potential, by a self-forcing and self-led fragmentation of the self, of the coherent subject of experience.

In Kierkegaard’s Concluding Unscientific Postscript, the person dedicated to the life of immediacy is “absolutely committed to relative ends”—this contradiction is rather like faith (also, references echo here as to how Hegel includes faith in unreflective knowledge) (9). In his Either/Or, the aesthete is pictured as Don Juan and Faust characters.

The ethical stage (Sittlichkeit in Hegel; the customs, societal, ethical norms) reveals the egoism of the aesthete as empty, as an escapist fancy, who despairs responsibility to the whole (community, the “universal”—in the sense of the specific ‘universe’ of the socially codified mores). It is a concretion of the abstract flights of the aesthetic. (We will see the necessary “suspension” of “ethics” in Fear and Trembling, which shows that Kierkegaard is holding out there being a power higher than that which establishes these social norms.)

The religious stage preserves the aesthetic force by the sense of possibility made infinite through the imagination. Here, though, because of the force of the ethical, the actual is as present as the potential. However, there is a very live question as to whether Kierkegaard (or anyone?) ever reaches the religious stage—instead, don’t we ever only reach the representation of the religious? Aren’t thought & language ideal? How, through the ideal, can one ever reach the actual?

Religion, for Kierkegaard, is not a matter of doctrine, dogma, or ritual; instead, it is a matter of passion, of individual, subjective passionate turning to the divine and beyond the human, beyond clerical mediation, beyond constructions or buildings or altars. It is only through faith that the individual has a chance to have true meaning; the illogical, anti-ethical, and inexpressible necessitates the self to make the self have value through choice—we choose eternity thereby choosing ourselves. This is a matter of electric freedom and paralyzing dread. It is only by the absurd that we have faith.

To praise Abraham as the “Father of Faith,” we ought to experience what he experienced (13). Thus, in the start of Fear and Trembling, the four versions of the Abraham story are used lyrically by Johannes, to point us to the dialectical in the sense that they render Abraham intelligible, but, becoming intelligible, these retellings do not show him to be the Father of Faith (12).

After the lyrical presentation, there is an attempt to experience these as thought: the dialectical investigation seen in the problemata. Thus, the dialectical part will be the exploration (but without synthesis) of this contradiction, which is one of ETHICS:

- For Hegel, both aesthetics and ethics of both base and religious types are in consciousness, thus can be rationalized, understood, and serve as steps to the absolute end we seek—they are equally valid routes to understanding, albeit an incomplete form of truth. A complete truth is in Absolute Spirit (Geist, not a religious category), which can be displayed somewhat to us through art (an appeal to bodily senses) or religion (appeal to senses and intellect), but most perfectly through philosophy (all that is manifest in art and religion then elevated to pure rationality).

- For Kierkegaard, ethics is the natural antithesis to aesthetics (keeping in mind that the antithesis preserves aspects of the thesis)—and is not so purely theoretically, but very much as lived experience. (In his Either/Or, we see this between “A” and “B,” the aesthetician and the judge; the correlation and discontinuity of lives between the one who lives in immediacy and the one who lives in reflection. In his F&T will see a different pairing of lives—the knight of infinite resignation and the knight of faith.)

“… a faith that has some inkling of its object

at the very edge of the field of vision

but remains separated from it

by a yawning abyss

in which despair plays its pranks”

--Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling, 54.

Image: Pablo Picasso, The Tragedy

(4) Fear & Trembling Outline / Overview:

Outline / Overview ... & Key Questions on Søren Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling: Dialectical Lyric by Johannes de silentio

- Author & Text Features & Frontispieces

- Author/Authors?

- Author: Søren Aabye Kierkegaard (1813-1855, Copenhagen, Denmark)

- Pseudonym: Johannes de silentio (Johannes = John; de silentio = of silence; Re: Grimm’s fairytale “The Faithful Servant”)

- Title & Subtitle:

- Biblical origin of “Fear and Trembling:”

- (e.g.: “fear & trembling seized me and made all my bones shake” (Job 4:14); “Fear & trembling have beset me; horror has overwhelmed me” (Psalm 55:5); “his affection for you is all the greater when he remembers that you were all obedient, receiving him with fear & trembling” (2 Cor. 7:15); etc., etc.)

- “Dialectical:” Plato, Hegel’s 3-part rational argumentative structure (thesis-antithesis-synthesis);

- “Lyric:” poem or song; poetic, personal expression, connected to feeling, esp. lightness, musicality;

- Consider the conjunction: “dialectical lyric” (Cf., akin Boethius’ prosimetrum in his The Consolation of Philosophy)

- Biblical origin of “Fear and Trembling:”

- Epigraph: (on the title page just before the preface)

- “What Tarquin the Proud said in his garden with the poppy blooms was understood by the son but not by the messenger” (Hamann; quoted in Kierkegaard, F&T, 39).

- What is its story? What do you make of the quote? Why use it to preface the work? Indirect communication?

- “What Tarquin the Proud said in his garden with the poppy blooms was understood by the son but not by the messenger” (Hamann; quoted in Kierkegaard, F&T, 39).

- Author/Authors?

- Preface:

- “Go further”—what is Johannes’ critique always going further? To what (for others and for Johannes)?

- Explain & evaluate: “Even if one were able to render the whole of the content of faith into conceptual form, it would not follow that one had grasped faith, grasped how one came to it, or how it came to one” (43).

- “Go further”—what is Johannes’ critique always going further? To what (for others and for Johannes)?

- Attunement: [Exordium] {{See Genesis 22 & Note on Mount Moriah, below}}

- How does he try to understand & therefore be able to speak about faith? How successful?

- What did Johannes seek to grasp in the story of Abraham: “For what occupied him was not the finely wrought fabric of imagination, but the shudder of thought” (44)?

- What is each story saying? What remains the same? What changes? Why repeatedly rewrite the story?

- Speech in Praise of Abraham: [Eulogy on Abraham] {{See Note on Textual Comparisons, below}}

- Explain the Hero and the Poet. Is Abraham a Hero? Did Abraham doubt?

- What gives Abraham his greatness? Can we understand Abraham?

- Problemata: “Preamble from the Heart” [“Preliminary Expectoration”]

- Dialectic

- Proverb’s application in ‘Outward World’ & ‘World of Spirit’ (57-58 ff.)

- Doubt & Go Further (41-43) Paradox (63) Knights (66)

- Anguish (“Angst,” aka ’Anxiety’, aka ’Dread’—all have no object, hence all vs. ‘fear’, which has an object)

- “What is left out of the Abraham story is the anguish” (58)Connection of Anguish & Courage (60, 63)

- Who? All (60); Johannes (60, 63); Abraham (75-77)

- Paradox

- Ethical Language vs. Religious Language (60) Incommensurability (76, 80)

- Absurd (absurdus: “out of tune, discordant, sense-less” (ab- “away, off” + -surdus “deaf, mute”); “that which is unheard of”)

- Faith as absurd (63, 65, 69-70, 75)

- Resignation (64-66) (to resign, but not as helpless abnegation, not giving up; it is an act of willing)

- Infinite Movement (65): infinite act of willing impossibility into possibility as its very renunciation

- Two-Step Movement (72): concentrate all to one wish; concentrate all to one act

- Infinite Resignation (67: as movement of faith; 74: peace in pain; 75: last step to faith)

- Knights (67-82)

- Knight of Faith

- Knight of Infinite Resignation

- Dialectic

- Problema I: Is there a Teleological Suspension of the Ethical?

- Teleology: the study of causes, ends, purpose, goal (telos: that to which & for which things aim): Compare: Aristotle’s “function argument” (Nicomachean Ethics): every thing that is, is for some purpose/reason, which is its function; perfecting one’s function yields arête (Greek, “excellence,” “virtue”), e.g.:

- Thing: Function: Perfection:

- Knife To cut Excellent, sharp, strong knife

- Plant To grow, reproduce Excellent, vigorous, healthy plant

- Human “Activity of soul in accord w/reason” Excellent, virtuous, happy person

- Ethics: (ethos: “character” as related to “custom”) the study of moral character & about moral judgments; examines spirit, disposition, behavior, & attributes of one’s self & relations to others; however, for F&T, the ethical is defined as: 1) norms of the society or whole; 2) a way of living with regard to and for the whole. Thus, to ask: “is there a teleological suspension of the ethical,” asks: can we judge actions or their purposes if suspended from consideration and judgment are the norms by which a society coheres and lives?

- For Aristotle: can you judge a knife’s excellence without regard to its ability to cut? Can you judge a person’s character/actions without regard to whether their reason is properly ruling over their desiring and sensitive aspects? For Kierkegaard: Can you judge a person’s character/actions without regard to their accord with universal, societal moral codes, in regard to others individually and the collective whole? If we cannot answer yes: we cannot think/judge Abraham a good man, the father of faith; but only a criminal.

- Teleology: the study of causes, ends, purpose, goal (telos: that to which & for which things aim): Compare: Aristotle’s “function argument” (Nicomachean Ethics): every thing that is, is for some purpose/reason, which is its function; perfecting one’s function yields arête (Greek, “excellence,” “virtue”), e.g.:

- The Ethical: vs. The Individual:

- universal (i.e., applies to all); particular;

- applies at every moment (i.e., always, for all); ethical task: express self in universal;

- immanent in itself (i.e., is its own telos (for itself)); assertion of particularity: sin, temptation;

- telos for all else (i.e., is the greatest good); redemption: reconcile one’s particularity with the

- furthest one can go (i.e., nothing higher, better, greater than it). universal (i.e., surrender part to the one).

- Thus … to “give oneself up” to the universal is “the highest that can be said of man and his existence,” is “a person’s eternal blessedness” (83). However … If the ethical is the highest end, the greatest good, then we are blameworthy for not “protesting loudly and clearly against the honour and glory enjoyed by Abraham as the father of faith when he should really be remitted to some lower court and exposed as a murderer” (84). Therefore … if we wish to uphold Abraham, whose movement is that of sin, we must suspend ethical judgment; for “faith is just this paradox, that the single individual is higher than the universal, though in such a way, be it noted, that the movement is repeated, that is, that, having been in the universal, the single individual now sets himself apart as the particular above the universal” (84).

- The Hero vs. Abraham:

- Stays within Ethical (no suspension of the ethical) Oversteps the Ethical (suspension of the ethical)

- Act’s telos expresses higher expression of the ethical Act’s telos in higher expression (faith)

- Parental ethical relation surrendered for societal ethical relation Parental suspended for faith relation

- Consequences:

- We cannot understand him: we cannot understand hubris as piety, evil as good, and goodness as sin

- “Then why does Abraham do it? For God’s sake, and what is exactly the same, for his own. He does it because God demands this proof of his faith; he does it for his own sake in order to be able to produce the proof” (88). So, go ahead, call Abraham’s act a trial, a temptation … but it is the ethical that tempts him from fulfilling God’s will.

- He cannot explain: language is universal; he has transgressed the universal, has no recourse to it

- “Then why does Abraham do it? For God’s sake, and what is exactly the same, for his own. He does it because God demands this proof of his faith; he does it for his own sake in order to be able to produce the proof” (88). So, go ahead, call Abraham’s act a trial, a temptation … but it is the ethical that tempts him from fulfilling God’s will. “Abraham cannot be mediated, … he cannot speak. The moment I speak I express the universal, and when I do not no one can understand me. So the moment Abraham wants to express himself … he has to say that his situation is one of temptation, for he has no higher expression of the universal that overrides the universal he transgresses” (89).

- How does he exist?

- “as the particular in opposition to the universal” (90)—to us, this can only appear to be sin; to Abraham, it is existence as faith: “That is the paradox that keeps him at the extremity and which he cannot make clear to anyone else, for the paradox is that he puts himself as the single individual in an absolute relation to the absolute” (90).

- We cannot understand him: we cannot understand hubris as piety, evil as good, and goodness as sin

(5) Fear & Trembling . . . (extended) Textual Analysis

TITLE PAGE:

“What Tarquin the Proud said in hid garden with the poppy blooms was understood by the son but not by the messenger” (Hamann).

- Note how this epigraph is an excellent example of indirect communication—Kierkegaard informs us—indirectly—of the role of indirect communication by an example of it: Tarquinius Seperbus, an early king of Rome, was at war with the Gabii; he sends his son off to seek refuge with the Gabii under the pretense that he was deserting his father due to ill treatment; the son becomes the leader of the Gabii; before his son’s messenger, Tarquinius slices off the tallest poppy flowers with his sword; the messenger had no idea what this meant, but relayed the action to the son, who understood perfectly well that his father was instructing him to “chop down” the tallest “poppies,” leading men of the Gabii by death or banishment; after doing so, the Gabii quickly surrendered to Tarquinius.

PREFACE:

“Go further:”

DOUBT: the reference is to Descartes, who is famous for his method of “hyperbolic” or “radical” doubt—question/doubt everything that may be false or full of error by suspending it from consideration (do so by swaths: doubt all sensory information, doubt reality by the fact that we cannot prove whether this is all real or just a dream, and doubt God’s goodness, for He may be an evil genius) so as to seek what is truly certain (which, he decides, is only that “I am, I exist,” or his cogito, ergo sum”). Despite doubting God’s goodness, Descartes professes his own faith, and offers (in his Meditations on First Philosophy) two proofs for God’s existence (and nature as good).

Kierkegaard/Johannes writes: “… everyone … is unwilling to stop with doubting everything. They all go further” (41, Hannay trans.). Where are they going?, he wonders … with the implication that we think ourselves past doubt … we rush to get answers … but have we sufficiently questioned things??? Doubt is the task of a lifetime! It is not done and we are not ready to move on to affirmative knowledge, to system building philosophy (i.e. Hegel) … but, this is precisely what we do today. “Today nobody will stop with faith; they all go further” (42).

Hence, the other reference here, under the topic of “going further” is DIALECTIC: since we do not stop with faith, are we to presume that we have already answered all its questions? We no longer do the foundational work, he charges. Where we go when we go further is to the “System,” by which he means Hegel’s dialectic. For Hegel, faith is just a stage in the spiraling of knowledge to its comprehensive conclusion in Absolute Spirit (Geist). Kierkegaard/Johannes claims to be no philosopher, to not have understood this system, whether there is one, or whether it has been completed.

“Even if one were to render the whole of the content of faith into conceptual form, it would not follow that one had grasped faith, grasped how one came to it, or how it came to one” (43).

He is no philosopher, but is “poetice et eleganter”—poetically and discriminatingly, or poetical and with a refinement or discriminating (taste) … these are terms Jerome is said (by Porphyrio in Carm. 1.24.5-6) is said to have said of the prophet Jeremiah (he was one who presented his ideas beautifully, his meanings eloquently)—an odd self-reference for Johannes, who otherwise claims a certain simplicity, although Jerome otherwise does not consider Jeremiah one of the prophets with an “ornate style,” unlike, say, Isaiah. But, Johannes goes on to say he writes in leisure and is happy if few appreciate it, for today’s age is one that has done away with passion (43). Note: passion is critical throughout.

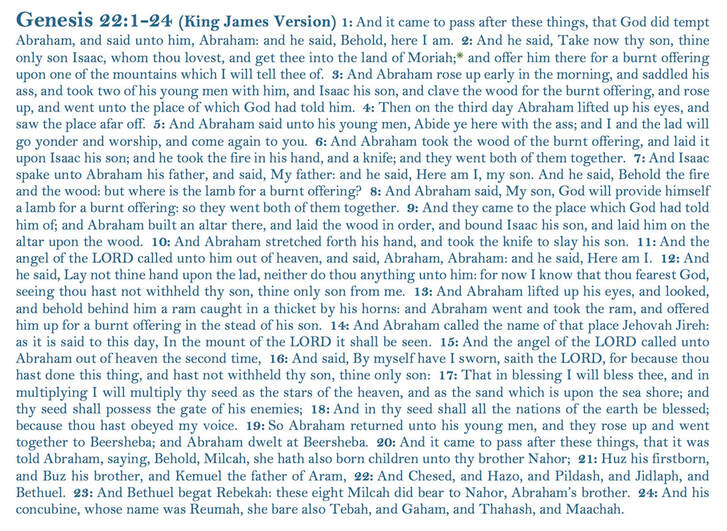

Genesis 22:1-13 (King James Version):

“And it came to pass after these things, that God did tempt Abraham, and said unto him, Abraham: and he said, Behold, here I am. And he said, Take now thy son, thine only son Isaac, whom thou lovest, and get thee into the land of Moriah; and offer him there for a burnt offering upon one of the mountains which I will tell thee of. And Abraham rose up early in the morning, and saddled his ass, and took two of his young men with him, and Isaac his son, and clave the wood for the burnt offering, and rose up, and went unto the place of which God had told him. Then on the third day Abraham lifted up his eyes, and saw the place afar off. And Abraham said unto his young men, Abide ye here with the ass; and I and the lad will go yonder and worship, and come again to you. And Abraham took the wood of the burnt offering, and laid it upon Isaac his son; and he took the fire in his hand, and a knife; and they went both of them together. And Isaac spake unto Abraham his father, and said, My father: and he said, Here am I, my son. And he said, Behold the fire and the wood: but where is the lamb for a burnt offering? And Abraham said, My son, God will provide himself a lamb for a burnt offering: so they went both of them together. And they came to the place which God had told him of; and Abraham built an altar there, and laid the wood in order, and bound Isaac his son, and laid him on the altar upon the wood. And Abraham stretched forth his hand, and took the knife to slay his son. And the angel of the LORD called unto him out of heaven, and said, Abraham, Abraham: and he said, Here am I. And he said, Lay not thine hand upon the lad, neither do thou any thing unto him: for now I know that thou fearest God, seeing thou hast not withheld thy son, thine only son from me. And Abraham lifted up his eyes, and looked, and behold behind him a ram caught in a thicket by his horns: and Abraham went and took the ram, and offered him up for a burnt offering in the stead of his son” (Genesis 22:1-13, KJV).

Johannes begins with a page about “a man” who had learned the story of Abraham and Isaac as a child, and, as he became older, became more and more attached to the story and less and less able to understand it. His singular desire was to meet Abraham and witness those events. Although, would bearing witness to them even help to understand them?? Presumably, not being a mere witness to, but to experience what Abraham had, would be the only way by which to understand. “For what occupied him was not the finely wrought fabric of imagination, but the shudder of thought” (44). Pay close attention here! The shudder of thought … the experience sought is pathos, the passionate suffering … you will not understand without feeling this shudder.

To step backwards a moment, let us frame the central point of Fear and Trembling as the question: “can faith be spoken about?” For Kierkegaard, no; but, we can speak in many ways of Abraham (13). If Kierkegaard can be seen as the father of existentialism, and existentialism can be seen as offering a primacy to emotive impulses over the rational (as explaining one critique of Hegel), we can see how we try to understand this story (use reason to render it comprehensible) by psychologizing it, filling out the details, but also obliterating its true meaning—the meaning it has precisely before it can be comprehensible. In this way we speak about Abraham.

Faith is an expression of the limit beyond which we cannot think. The faithful exile themselves from human language/discourse. Abraham’s faith is an affront to human society (11). “… If we are to talk of faith at all it is of something we cannot explain in any language that suffices for people to describe and justify their actions and attitudes to one another” (11).

Kierkegaard/Johannes criticizes his contemporaries for believing faith as a beginning and not as an end—views this as a cheapened conception (12). (Likewise, today, after Nietzsche’s proclamation that God is dead, Marx’s religion as an opiate mantra, we think that we have ‘solved’ the ‘God problem’ and need not confront its questions).

Images: top left: William Blake, Abraham and Isaac, 1799-1800, Yale Center for British Art; bottom left: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, The Sacrifice of Isaac, ca. 1750s , The Met; right: Rembrandt, Sacrifice of Isaac, 1635, Hermitage Museum.

Abraham’s faith is that he would have his son saved or restored (not proving existence of God). Thus, the greatness of his faith is: (1) in respect of his love (God); (2) what he confidently expected (the impossible, his son living); (3) what he strove with (God) (14).

Before going back to the text, note that “the man” desires to walk with Abraham and Isaac on that three day journey up Mount Moriah:

Now … back to the text … we get four versions of Abraham’s sacrifice followed, in turn, with a parable or anecdote about a child being weaned from its mother. What do you think the meaning of these following parables or morals might be? What is the meaning of these four versions of the story? How do they make you feel? How does their lyrical presentation affect the meaning and you?

After the initial page of remarks by Johannes, speaking in the third person, about the attraction but impossibility to understand the story of Abraham and Isaac, there are four variations offered on the story, each seeks to make it understandable. Following each variation is an elliptical analogy of a child and mother. These speak to the variations, but their interpretations are challenging and open.

I) Abraham tells Isaac where they are going and what he must do. Isaac failed to understand and pleaded for his life; he cried to God to have mercy on him and denies his earthly father. Abraham thanks God, beneath his breath, thinking it better for his son to fear him and think him a monster than to blame God for what was about to happen.

II) Abraham proceeds in silence, at last, sees the ram, and sacrifices that in his son’s stead; but, ever after, he “… Abraham’s eye was darkened, he saw joy no more” (46).

III) Abraham draws the knife, and presumably the ram appears again, but Abraham also throws himself to the ground, seeing his willingness to act as a sin, begs God’s forgiveness, knowing not how he could ever be forgiven such a horrid sin.

IV) In the moment before the act’s aversion, Isaac sees “… Abraham’s left hand … clenched in anguish, that a shudder went through his body …” and saw his father draw the knife (47). His hand was stopped, but thereafter Isaac lost his faith. Isaac never told that he saw what was to have come; Abraham never knew his son had seen.

Notice how Johannes ends … “In these and similar ways this man of whom we speak thought about those events. Every time he came home from a journey to the mountain in Moriah he collapsed in weariness, clasped his hands, and said: ‘Yet no one was as great as Abraham; who is able to understand him?’”” (48). This “man” has accompanied Abraham many times—reliving, imaginatively, experientially, passionately—up the mountain. He has gone there many times, and understands less each time, feels more each time. What does he feel: perplexity. Perhaps, what are we grasp, then?

Abraham’s faith is that he would have his son saved or restored (not proving existence of God). Thus, the greatness of his faith is: (1) in respect of his love (God); (2) what he confidently expected (the impossible, his son living); (3) what he strove with (God) (14).

Before going back to the text, note that “the man” desires to walk with Abraham and Isaac on that three day journey up Mount Moriah:

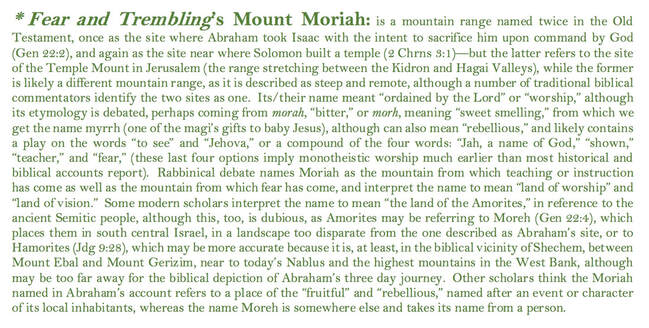

- Mount Moriah: variously: the mountain range named in Genesis; the site where Abraham took Isaac with the intent to sacrifice him upon command by God (Genesis 22:2); the site of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem (the range stretching between the Kidron Valley and Hagai Valley); the site near where Solomon built a temple (2 Chronicles 3:1). Its name meant “ordained by the Lord;” the etymology has been debated, perhaps coming from morah, “bitter,” or “morh,” meaning sweet smelling,” from which we get the name myrrh. Rabbinical debate has identified it as the mountain from which teaching or instruction has come as well as the mountain from which fear has come; additional Rabbinic writings interpret the name to mean “the land of worship” and the “land of vision.” Modern scholars interpret the name to mean “the land of the Amorites,” in reference to the ancient Semitic people. –I consider these differences to be particularly interesting for the contrasts of “bitter” and “sweet” and then “teaching” and “fear,” playing on the contrasts Kierkegaard offers throughout Fear and Trembling.

Now … back to the text … we get four versions of Abraham’s sacrifice followed, in turn, with a parable or anecdote about a child being weaned from its mother. What do you think the meaning of these following parables or morals might be? What is the meaning of these four versions of the story? How do they make you feel? How does their lyrical presentation affect the meaning and you?

After the initial page of remarks by Johannes, speaking in the third person, about the attraction but impossibility to understand the story of Abraham and Isaac, there are four variations offered on the story, each seeks to make it understandable. Following each variation is an elliptical analogy of a child and mother. These speak to the variations, but their interpretations are challenging and open.

I) Abraham tells Isaac where they are going and what he must do. Isaac failed to understand and pleaded for his life; he cried to God to have mercy on him and denies his earthly father. Abraham thanks God, beneath his breath, thinking it better for his son to fear him and think him a monster than to blame God for what was about to happen.

II) Abraham proceeds in silence, at last, sees the ram, and sacrifices that in his son’s stead; but, ever after, he “… Abraham’s eye was darkened, he saw joy no more” (46).

III) Abraham draws the knife, and presumably the ram appears again, but Abraham also throws himself to the ground, seeing his willingness to act as a sin, begs God’s forgiveness, knowing not how he could ever be forgiven such a horrid sin.

IV) In the moment before the act’s aversion, Isaac sees “… Abraham’s left hand … clenched in anguish, that a shudder went through his body …” and saw his father draw the knife (47). His hand was stopped, but thereafter Isaac lost his faith. Isaac never told that he saw what was to have come; Abraham never knew his son had seen.

Notice how Johannes ends … “In these and similar ways this man of whom we speak thought about those events. Every time he came home from a journey to the mountain in Moriah he collapsed in weariness, clasped his hands, and said: ‘Yet no one was as great as Abraham; who is able to understand him?’”” (48). This “man” has accompanied Abraham many times—reliving, imaginatively, experientially, passionately—up the mountain. He has gone there many times, and understands less each time, feels more each time. What does he feel: perplexity. Perhaps, what are we grasp, then?

|

“If there were no eternal consciousness in a man, if at the bottom of everything there were only a wild ferment, a power that twisting in dark passions produced everything great or inconsequential; if an unfathomable, insatiable emptiness lay hid beneath everything, what would life be but despair? … how empty and devoid of comfort life would be!” --Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling, 49. Image: Rodin, The Clenched Hand |

SPEECH IN PRAISE OF ABRAHAM:

“If there were no eternal consciousness in a man, of at the bottom of everything there were only a wild ferment, a power that twisting in dark passions produced everything great or inconsequential; if an unfathomable, insatiable emptiness lay hid beneath everything, what would life be but despair? … how empty and devoid of comfort life would be!” (49).

Consider the beauty of this language … the passionate, lyrical nature of its words and meaning. The beauty is horrible, to be sure, but is it not compelling? How miserable it would all be … how horrible would life be … how empty life would be, were there not an eternal consciousness … were there not a meaning and a cause, life would be naught be despair. … BUT … is this not how life is for the person of faith? Is not the one with faith, by the testament of this work, one who is an exile from communicability, thus, from community?

Hero & Poet:

- The hero and poet forge community and also include the faithful in community (yanking them in) by telling about them. The hero struggles and the poet beautifies his act and memorializes it. No one who is great will be forgotten. The tone is sorrowful and passionate and has an optimism through it … but it is fighting against truth. The tone does not seem ironic, but genuine … perhaps, then, sometimes we can will ourselves to believe in this memorial, in immortality, in the goodness of the struggle. (Cf., Miguel de Unamuno’s The Tragic Sense of Life, namely the second to last chapter detailing an ethic of invasion that permits immortality—that for which we all long.)

- All will be remembered in proportion to their greatness. And, Abraham is the greatest of them all. He is the “Father of Faith.” He is the one “great with that power whose strength is powerlessness, great in that wisdom whose secret is folly, great in that hope whose outward form is insanity, great in that love which is hatred of self” (50).

Abraham: His faith permitted him all these greatnesses; “He left behind his worldly understanding and took with him his faith” (50). He left … his greatness, his faith, was such that he could not remain in the public sphere, in the world, amongst ordinary comprehension. He, the Knight of Faith, is certainly (if any are at all) in the world—perhaps a neighbor, a passerby, a bourgeoisie—but, cannot be one of us, for we cannot understand him. He cannot understand himself, either: “If only he had been disowned, cast out from God’s grace, he would have understood it better. As it was it looked more like a mockery of himself and his faith” (51).

- (Notice the poetic repetition throughout this section; lines, like “From Abraham we have no song of sorrow” (51), are repeated as if by a chorus as Johannes attempts the praise of Abraham like the poet. But, we see, this collapses: Abraham is no hero.)

If he had not been God’s chosen one, he may have been great to some, but would have been forgotten. It is only with the horror that comes from being such that one can become great. But, he believed, and never wavered. And his reward? The horror: God came and asked him to take his son, his only son, the son prophesied to lead great nations of the faithful, the son miraculously born so late to them, to take this son up a mountain and slay him as sacrifice (52-53; Genesis 22:1-13). But, Abraham did not doubt.

- (Would we not, were we in his position, wonder if this was the devil, at the very least, instead of the will of God—some small doubt, at least?)

Abraham did not doubt. But, what was his faith in? This is not in God’s existence, but his faith was “… a faith that has some inkling of its object at the very edge of the field of vision but remains separated from it by a yawning abyss in which despair plays its pranks” (54).

If Abraham was a hero, as is first indirectly suggested here, he would have raced up Mount Moriah and sent the blade into his own heart. A tragic, but noble sacrifice of the father for the son. But, Abraham did not do this, is not a hero; he is the father of faith. He had faith. Thus, he obeyed, without question.

To Abraham, Johannes closes: “… in one hundred and thirty years you got no further than faith” (56).

Where would one go, if one went further? (Recall, of course, the Preface’s disdain for the hurried “furthering.”) Presumably, the only options are to understanding (which Johannes is telling us is impossible), or to skepticism (which seems to be incompatible with the very nature of faith).

Image: Donatello, Sacrificio di Isacco, 1421, Museu dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence

PROBLEMATA: “Preamble from the Heart” (“Preliminary Expectoration”)

“… faith begins precisely where thinking leaves off” (82).

Key concepts to wrestle with in this section:

|

Anguish

Courage Paradox Absurd Resignation |

Infinite Resignation

Knight of Faith Knight of Infinite Resignation Infinite Movement Incommensurability (80) |

(({})) Dialectic

The “Preamble” begins with a distinction between the:

Keep in mind the earlier discussions of Kierkegaard’s animosity towards the domination of academia and all discussions by Hegel’s philosophy, namely, the domination of his “dialectic” and the premise that faith is a stage that is moved beyond by philosophy. Also remember that Kierkegaard is using a dialectic herein; his is similar in many ways to Hegel’s three-step (thesis, antithesis, and synthesis), yet used as a critique. Thus, keep in mind that we will see the constant issuance of “threes,” of pairs of contraries or contrasts that seek resolution in something further; and, as a mode of critique, keep an eye out for when this resolution is impossible, when the incommensurability and the paradox cannot be resolved or made sensible. Thus, again, note that the “Preamble” begins with this distinction between the outer world and the world of spirit.

The outer world is where imperfection reigns (people work hard and don’t get bread, people who are lazy do get bread, etc.). Other parallels to the outer that we will see include the finite, reality, actuality, the masses, etc. This is the everyday world. The world of spirit is the inner world; in it, eternal order reigns (God’s justice is certain and indubitably fair). Other parallels to the world of spirit include the transcendent and the infinite.

(({})) The Necessity of Labor

Society constantly wants to think it has faith and can move beyond it; that “… it is enough to have knowledge of large truths” (58); that it understands Abraham.

“Now the story of Abraham has the remarkable quality that is will always be glorious no matter how impoverished out understanding of it, but only—for it is true here too—if we are willing to ‘labour and be heavy laden.’ But labour they will not, and yet they still want to understand the story” (58).

Necessity of struggle and anguish to understand Abraham (58):

Speaking in his honor, we make his story into a commonplace* (‘he offered God the best he had’ –to which Kierkegaard rails: no! Well, true, but, no! “What is left out of the Abraham story is the anguish …” (58)). We talk and talk and talk about Abraham as the “father of faith,” but, we do not understand Abraham. We cannot understand Abraham. … But, we could try …

*: Note: compare this passage to p. 61 and p. 81, where Johannes, himself, offers two steps each as to how he would go about telling the story of Abraham.

Understanding requires an affective experience—and, not just ‘experience’ in the sense of going through an act like that, but to affectively suffer the thought, to suffer along with the thought. This demonstrates the integral role of the passions in understanding (cf. his note on p.71: “What we lack today is not reflection but passion”).

(({})) Anguish / Anxiety

In the Danish, the term that he uses is “Angst” (which is the same in German, where we find the term and idea in the works of Heidegger, as inspired by Kierkegaard). The term is translated as “Anguish” in the Hannay translation and “Anxiety” in the Hong and Hong translation; it is also sometimes translated as “Dread.”

What is anxiety?

It is not fear—fear has an object (e.g., “I am afraid of the monster”); anxiety has no object (e.g., “I am incredibly anxious about … I don’t know … I do know … but, I don’t … I cannot say … but, I … but …”). It is affective. You do not think anxiety; you suffer anxiety. (Thus, we would call anxiety something passionate—“passion” from “pathos,” “that which you suffer,” and which is in contrast to ethos, “character and custom,” and logos, “reason, argument, word”--but, just because we are calling it passionate and affective, this does not mean the same thing exactly as being something “emotional.” There is some difference that needs to be worked out here. Also, I’d like to develop a tie between the anxious and the aesthetic.) (Note: Kierkegaard’s book The Concept of Anxiety was published nine months after F&T, under the pseudonym of Vigilius Haufniensis, and focuses all of its attention on this idea of anxiety.)

Abraham’s story reveals the incommensurability of its ethical expression with its religious expression (60). Ethically expressed: Abraham is willing to murder his son [insane, criminal]. Religiously expressed: Abraham is wiling to sacrifice his son [for God, for his faith, out of faith].

(({})) Courage

Johannes tells us that we must seek to understand Abraham by labor. We must take up and struggle with the story. Only through affective address of and by anguish can we hope to understand Abraham. Most of us are not brave enough to deal with this honest address because most of us are unable to risk thinking through anguish. It is dangerous, he tells us. “If one hasn’t the courage to think this thought through, to say that Abraham was a murderer, then surely it is better to acquire that courage than to waste time on undeserved speeches in his praise” (60). Towards the end of his “Preamble,” he similarly implores: “So let us either forget all about Abraham or learn how to be horrified at the monstrous paradox which is the significance of his life, so that we can understand that our time like any other can be glad if it has faith” (81). To learn how to be horrified is to gain courage.

Thus, of courage, there are different levels or types. We all need courage to think the story of Abraham truly, which is to think anguish. Johannes says he is brave, has courage, but has no faith. The two types of Knights have courage, but of different types.

“For my own part I don’t lack the courage to think a thought whole. No thought has frightened me so far” (60). Yet … “I have seen horror face to face, I do not flee it in fear but know very well that, however bravely I face it, my courage is not that of faith and not at all to be compared with it. I cannot close my eyes and hurl myself trustingly into the absurd, for me it is impossible …” (63). –But … do not take his statement that he has not faith to mean that he does not believe in God or that he does not love God … “I am convinced that God is love; this thought has for me a pristine lyrical validity. When it is present to me I am unspeakably happy, when it is absent, I yearn for it more intensely than the lover for the beloved; but I do not have faith; this courage I lack” (63).

(({})) The Knights

The two knights—The Knight of Infinite Resignation and The Knight of Faith—are depictions or personifications of stages:

Abraham is the “father of faith,” he stands at an “extremity;” “The last stage he loses sight of is infinite resignation. He really goes further and comes to faith” (66).

They are also like a dialectic, and they both contain dialectical movements:

“The dialectic of faith is the most refined and most remarkable of all dialectics,

it has an elevation that I can form of conception of but no more” (66).

We can see them related to—although not directly mapping onto—the dialectical stages worked out above of the aesthetic, the ethical, and the religious. How we think of them as a dialectic is up to interpretation. One way to consider how this is a dialectic is as the following:

The “Preamble” begins with a distinction between the:

- Outward World: subject to the law of imperfection

- World of Spirit: eternal divine order prevails (57).

Keep in mind the earlier discussions of Kierkegaard’s animosity towards the domination of academia and all discussions by Hegel’s philosophy, namely, the domination of his “dialectic” and the premise that faith is a stage that is moved beyond by philosophy. Also remember that Kierkegaard is using a dialectic herein; his is similar in many ways to Hegel’s three-step (thesis, antithesis, and synthesis), yet used as a critique. Thus, keep in mind that we will see the constant issuance of “threes,” of pairs of contraries or contrasts that seek resolution in something further; and, as a mode of critique, keep an eye out for when this resolution is impossible, when the incommensurability and the paradox cannot be resolved or made sensible. Thus, again, note that the “Preamble” begins with this distinction between the outer world and the world of spirit.

The outer world is where imperfection reigns (people work hard and don’t get bread, people who are lazy do get bread, etc.). Other parallels to the outer that we will see include the finite, reality, actuality, the masses, etc. This is the everyday world. The world of spirit is the inner world; in it, eternal order reigns (God’s justice is certain and indubitably fair). Other parallels to the world of spirit include the transcendent and the infinite.

(({})) The Necessity of Labor

Society constantly wants to think it has faith and can move beyond it; that “… it is enough to have knowledge of large truths” (58); that it understands Abraham.

“Now the story of Abraham has the remarkable quality that is will always be glorious no matter how impoverished out understanding of it, but only—for it is true here too—if we are willing to ‘labour and be heavy laden.’ But labour they will not, and yet they still want to understand the story” (58).

Necessity of struggle and anguish to understand Abraham (58):

Speaking in his honor, we make his story into a commonplace* (‘he offered God the best he had’ –to which Kierkegaard rails: no! Well, true, but, no! “What is left out of the Abraham story is the anguish …” (58)). We talk and talk and talk about Abraham as the “father of faith,” but, we do not understand Abraham. We cannot understand Abraham. … But, we could try …

*: Note: compare this passage to p. 61 and p. 81, where Johannes, himself, offers two steps each as to how he would go about telling the story of Abraham.

Understanding requires an affective experience—and, not just ‘experience’ in the sense of going through an act like that, but to affectively suffer the thought, to suffer along with the thought. This demonstrates the integral role of the passions in understanding (cf. his note on p.71: “What we lack today is not reflection but passion”).

(({})) Anguish / Anxiety

In the Danish, the term that he uses is “Angst” (which is the same in German, where we find the term and idea in the works of Heidegger, as inspired by Kierkegaard). The term is translated as “Anguish” in the Hannay translation and “Anxiety” in the Hong and Hong translation; it is also sometimes translated as “Dread.”

What is anxiety?

It is not fear—fear has an object (e.g., “I am afraid of the monster”); anxiety has no object (e.g., “I am incredibly anxious about … I don’t know … I do know … but, I don’t … I cannot say … but, I … but …”). It is affective. You do not think anxiety; you suffer anxiety. (Thus, we would call anxiety something passionate—“passion” from “pathos,” “that which you suffer,” and which is in contrast to ethos, “character and custom,” and logos, “reason, argument, word”--but, just because we are calling it passionate and affective, this does not mean the same thing exactly as being something “emotional.” There is some difference that needs to be worked out here. Also, I’d like to develop a tie between the anxious and the aesthetic.) (Note: Kierkegaard’s book The Concept of Anxiety was published nine months after F&T, under the pseudonym of Vigilius Haufniensis, and focuses all of its attention on this idea of anxiety.)

Abraham’s story reveals the incommensurability of its ethical expression with its religious expression (60). Ethically expressed: Abraham is willing to murder his son [insane, criminal]. Religiously expressed: Abraham is wiling to sacrifice his son [for God, for his faith, out of faith].

(({})) Courage

Johannes tells us that we must seek to understand Abraham by labor. We must take up and struggle with the story. Only through affective address of and by anguish can we hope to understand Abraham. Most of us are not brave enough to deal with this honest address because most of us are unable to risk thinking through anguish. It is dangerous, he tells us. “If one hasn’t the courage to think this thought through, to say that Abraham was a murderer, then surely it is better to acquire that courage than to waste time on undeserved speeches in his praise” (60). Towards the end of his “Preamble,” he similarly implores: “So let us either forget all about Abraham or learn how to be horrified at the monstrous paradox which is the significance of his life, so that we can understand that our time like any other can be glad if it has faith” (81). To learn how to be horrified is to gain courage.

Thus, of courage, there are different levels or types. We all need courage to think the story of Abraham truly, which is to think anguish. Johannes says he is brave, has courage, but has no faith. The two types of Knights have courage, but of different types.

“For my own part I don’t lack the courage to think a thought whole. No thought has frightened me so far” (60). Yet … “I have seen horror face to face, I do not flee it in fear but know very well that, however bravely I face it, my courage is not that of faith and not at all to be compared with it. I cannot close my eyes and hurl myself trustingly into the absurd, for me it is impossible …” (63). –But … do not take his statement that he has not faith to mean that he does not believe in God or that he does not love God … “I am convinced that God is love; this thought has for me a pristine lyrical validity. When it is present to me I am unspeakably happy, when it is absent, I yearn for it more intensely than the lover for the beloved; but I do not have faith; this courage I lack” (63).

(({})) The Knights

The two knights—The Knight of Infinite Resignation and The Knight of Faith—are depictions or personifications of stages:

Abraham is the “father of faith,” he stands at an “extremity;” “The last stage he loses sight of is infinite resignation. He really goes further and comes to faith” (66).

They are also like a dialectic, and they both contain dialectical movements:

“The dialectic of faith is the most refined and most remarkable of all dialectics,

it has an elevation that I can form of conception of but no more” (66).

We can see them related to—although not directly mapping onto—the dialectical stages worked out above of the aesthetic, the ethical, and the religious. How we think of them as a dialectic is up to interpretation. One way to consider how this is a dialectic is as the following:

- Thesis: all those today who think they “have” faith; those masses—all of us—who exist in this “reality,” wherein we share the same general language, norms, ways of understanding things.

- Antithesis: the Knight of Infinite Resignation.

- Synthesis: the Knight of Faith.

- “Resignation does not require faith …” (77): suggests that resignation cannot be the synthesis (because the synthesis must preserve moments of both the thesis and antithesis), and thus must be one of the two opposites. The Knight of Resignation is described as “… a stranger, a foreigner” (79), which suggests that it is not the ethical, since the ethical is that stage concerned with norms, with the universals of a particular society. This means that Resignation would be the opposite of the ethical, thus, the aesthetic. Considering that he describes the Knight of Infinite Resignation through a story about a lad who loved a princess, whom he could not have, and then made the impossible become possible by its abstraction into a spiritual expression (i.e., preserve the memory of her, and renounce the actuality of having her), this seems most closely descriptive of the aesthetic stage.

Gustave Doré, Abraham and Isaac Climb Mt. Moriah

Gustave Doré, Abraham and Isaac Climb Mt. Moriah

Let us consider the two Knights more closely:

~~~(({}))~~~ The Knight of Infinite Resignation:

“The knights of infinite resignation are readily recognizable, their gait is gliding, bold” (67).

Discovering that one’s ultimate desire is impossible, it is an “ideality” that cannot be translated into “reality” or “actuality,” this knight does not give it up: “… he does not renounce the love, not for all the glory in the world. … He first makes sure that this really is the content of his life …. He is not cowardly, he is not afraid to let his love steal in upon his most secret, most hidden thoughts, to let it twine itself in countless coils around every ligament of his consciousness … He feels a blissful rapture … for this moment is life and death. Having thus imbided all the love and absorbed himself in it, he does not lack the courage to attempt and risk everything” (71). He has passion. He has the strength to concentrate the whole of his life and the whole of the meaning of reality in a single wish (72). He has “… the strength to concentrate the whole of the result of his reflection into one act of consciousness” (72).

(({})) Infinite Movement

This concentration is the act of resignation, which he must perform infinitely. This concentration is on the impossibility that is made possible by expressing it spiritually—this spiritual expression actualizes the impossibility into possibility, but, it is also an act of renouncing it. Thus, this concentration is the act of renunciation.

Resignation, then, is not a helpless abnegation; it is not giving up; it is an act of willing. An infinite willing. An act of willing the impossibility into a possibility, which is its very renunciation.

This knight does not forget his ultimate wish. Instead, he must remember it: “… the memory is precisely the pain, and yet in his infinite resignation he is reconciled with existence” (72). It is a painful memory, like a bad bruise, that one keeps pressing over and over; re-feeling its pain is a way to “keep it,” when, in reality, you were never allowed to have it—it was impossible. The impossibility made this painful bruise; but, by always pushing at the bruise, you have what was not possible to have (cf., 72-3).

~~~(({}))~~~ The Knight of Faith:

“But those who wear the jewel of faith can easily disappoint, for their exterior bears a remarkable similarity to what infinite resignation itself as much as faith scorns, namely the bourgeois philistine” (67).

Johannes says he is no knight of faith; he knows no one like this; he would journey wherever to see such a man or woman; but, he can imagine what one would be like: “Good God! Is this the person, is it really him? He looks just like a tax-gatherer” (68).

This imagined knight knows that he hasn’t a penny, but knows surely that his wife will have a phenomenal delicacy for him for dinner; if she has, he would eat it with relish shocking to all, and, if she hasn’t, anything she serves will be eaten with the same relish (cf., 69). “… not the least thing does he do except on the strength of the absurd. … and yet this man has made and is at every moment making the movement of infinity. He drains in infinite resignation the deep sorrow of existence, he knows the bliss of infinity, he has felt the pain of renouncing everything, whatever is most precious in the world, and yet to him finitude tastes just as good as to one who has never known anything higher. … He resigned everything infinitely, and then took everything back on the strength of the absurd” (69-70).

(({})) Faith

Certainty versus Faith (76)—these are not the same; the latter needs the recognition of the impossible.

(({})) Paradox

From the Greek para- (counter to) plus -doxa (opinion), indicating those statements that counter our beliefs and expectations, a paradox is a statement that is absurd or fantastic, but, importantly, something that is not yet actually illogical, no matter its being seemingly self-contradictory. The most important to pay attention to here is that between Ethical and Religious Languages (60): ethically explicated, Abraham is willing to murder his son; religiously explained, Abraham is willing to sacrifice his son--the paradox being that both expressions are accurate, even as they ever contradict. Further key to grasping paradox, is the final theme demanding attention:

(({})) Incommensurability

The "incommensurable," coming from the Latin conjunctions of in- (not, opposite), -con- (with, together), and -mensurabilis (measurable), hence, that which is not-together-measurable, two or more matters that share nothing by which they could both be equitably measured ...

~~~(({}))~~~ The Knight of Infinite Resignation:

“The knights of infinite resignation are readily recognizable, their gait is gliding, bold” (67).

Discovering that one’s ultimate desire is impossible, it is an “ideality” that cannot be translated into “reality” or “actuality,” this knight does not give it up: “… he does not renounce the love, not for all the glory in the world. … He first makes sure that this really is the content of his life …. He is not cowardly, he is not afraid to let his love steal in upon his most secret, most hidden thoughts, to let it twine itself in countless coils around every ligament of his consciousness … He feels a blissful rapture … for this moment is life and death. Having thus imbided all the love and absorbed himself in it, he does not lack the courage to attempt and risk everything” (71). He has passion. He has the strength to concentrate the whole of his life and the whole of the meaning of reality in a single wish (72). He has “… the strength to concentrate the whole of the result of his reflection into one act of consciousness” (72).

(({})) Infinite Movement

This concentration is the act of resignation, which he must perform infinitely. This concentration is on the impossibility that is made possible by expressing it spiritually—this spiritual expression actualizes the impossibility into possibility, but, it is also an act of renouncing it. Thus, this concentration is the act of renunciation.

Resignation, then, is not a helpless abnegation; it is not giving up; it is an act of willing. An infinite willing. An act of willing the impossibility into a possibility, which is its very renunciation.

This knight does not forget his ultimate wish. Instead, he must remember it: “… the memory is precisely the pain, and yet in his infinite resignation he is reconciled with existence” (72). It is a painful memory, like a bad bruise, that one keeps pressing over and over; re-feeling its pain is a way to “keep it,” when, in reality, you were never allowed to have it—it was impossible. The impossibility made this painful bruise; but, by always pushing at the bruise, you have what was not possible to have (cf., 72-3).

~~~(({}))~~~ The Knight of Faith:

“But those who wear the jewel of faith can easily disappoint, for their exterior bears a remarkable similarity to what infinite resignation itself as much as faith scorns, namely the bourgeois philistine” (67).

Johannes says he is no knight of faith; he knows no one like this; he would journey wherever to see such a man or woman; but, he can imagine what one would be like: “Good God! Is this the person, is it really him? He looks just like a tax-gatherer” (68).

This imagined knight knows that he hasn’t a penny, but knows surely that his wife will have a phenomenal delicacy for him for dinner; if she has, he would eat it with relish shocking to all, and, if she hasn’t, anything she serves will be eaten with the same relish (cf., 69). “… not the least thing does he do except on the strength of the absurd. … and yet this man has made and is at every moment making the movement of infinity. He drains in infinite resignation the deep sorrow of existence, he knows the bliss of infinity, he has felt the pain of renouncing everything, whatever is most precious in the world, and yet to him finitude tastes just as good as to one who has never known anything higher. … He resigned everything infinitely, and then took everything back on the strength of the absurd” (69-70).

(({})) Faith

Certainty versus Faith (76)—these are not the same; the latter needs the recognition of the impossible.

(({})) Paradox

From the Greek para- (counter to) plus -doxa (opinion), indicating those statements that counter our beliefs and expectations, a paradox is a statement that is absurd or fantastic, but, importantly, something that is not yet actually illogical, no matter its being seemingly self-contradictory. The most important to pay attention to here is that between Ethical and Religious Languages (60): ethically explicated, Abraham is willing to murder his son; religiously explained, Abraham is willing to sacrifice his son--the paradox being that both expressions are accurate, even as they ever contradict. Further key to grasping paradox, is the final theme demanding attention:

(({})) Incommensurability

The "incommensurable," coming from the Latin conjunctions of in- (not, opposite), -con- (with, together), and -mensurabilis (measurable), hence, that which is not-together-measurable, two or more matters that share nothing by which they could both be equitably measured ...

- (... as illustration, we might colloquially say such a case is like comparing oranges and apples, but that is not actually a precise expression, for both are pieces of fruit, hence, however wobbly, giving us a common ground by which to judge the two things; so, what example really best captures something incommensurate? Consider Johannes'/Kierkegaard's paradox of ethical language versus religious language ... within either realm, there are ways to measure what Abraham did: ethics can have any number of systems to judge it (as a violation of character ethics, he was willing wrongly; as a wrong in normative ethics, he was violating a law against killing; in Utilitarian ethics, his otherwise bad act was not justified by doing the most good for the most people; etc.), just as religion can have any number of justifications by which it would validly call it sacrifice (God's will is incomprehensible, but must always be followed, for it is truth; Sacred literature and innumerable philosophical arguments on religious principles can support this)--yet, there is no ethical system that can validly bow to the authority of the religious means of judgment, just as the religious frame of judgment cannot wholly cede to the authority of reason in the ethical means of judgment: hence, there is no measure by which to judge Abraham that is wholly just or fair to the first principles and means of judging within both realms of language.)

Problema I: Is there a Teleological Suspension of the Ethical?

First, let us understand the section's titular question:

- Telos: Greek for “end,” “purpose;” it is the goal or final cause to which or for which one acts/is.

- Teleology: is the study of causes, ends, and/or those things that would tell us about the purpose, aims, intentions, and/or ends of things. In essence, it is a study reliant upon questions of purpose.

- Think for example of Aristotle’s “function argument” in his Nicomachean Ethics: there, he argues that every thing that is, is for some purpose or reason. Everything has a function, which is this purpose for which it is meant. The function of a knife is to cut; the function of an eye is to see; the function of a plant is to grow and reproduce; the function of a puppy dog is to be “man’s best friend;” the function of a human is “activity of the soul in accordance with reason”--i.e., to use reason, our highest capacity, in such a way to harmonize the behavioral and nutritive levels of the soul (so our drives and actions act in obedience to what reason tells them).

However … for Kierkegaard, we have to take the last part of the phrase into consideration … that which is being suspended from consideration here is the notion of the ends or goals of the ethical.

What is the ethical, for Kierkegaard?

Remember, we differentiated two different aspects:

1) the ethical as the norms of the society or whole;

2) the ethical as the way of living with regard to and for the whole.

The suspension, then, is going to take away consideration as to the standards or norms and the purposes behind or for these standards and norms.

- We will not consider, e.g., the Ten Commandments, the Constitution, the civilian law, basic civic decorum; we will not consider any systems dictating how to hold your fork or ordering you to help a little old lady across the street. Further, we will not consider why we have these norms, any reasons or purposes or motivations in, behind, or of these norms.

- ... Pause ... Think through how radical this is! ...

- ... How do we then judge something?

- (imagine me asking you to tell me the distance between Nashville and New York City, but you were not allowed to use any units of spatial measuring like miles, yards, or feet ... so, with no extra long ruler, how do you judge how far away the one is from the other? ... Or ... to maintain the 'moral' pressure of what he is seeking to judge here, imagine someone just walked in the room and slapped you really hard; you 'feel' this to be very wrong, but how do you argue its injustice without appealing to anything like institutional rules or civil laws on behavior to others, without crying out about the Golden Rule, etc.?)

- … Is there any case by which we would want to judge a person or an action wherein we do not take into consideration the norms of human conduct or the purposes behind the norms?