Jean-Luc Nancy’s Noli me tangere: On the Raising of the Body

|

Jean-Luc Nancy, Noli me Tangere: On the Raising of the Body, trans. Sarah Clift, Pascale-Anne Brault, Michael Naas (NY: Fordham University Press, 2008).

C O N T E N T S :

|

Introductory Thoughts:

This work is thoroughly aesthetic (per Greek aesthesis, “perception by the senses,” but emphasizing link of ‘sense’ as bodily perception and as a form of understanding). Its content explores the “don’t touch me” as a parable and as represented in art to open up what it means beyond what it says; its theory asks about sensible perception, explores the meaning of touch, sight, hearing, passions, etc., as it deconstructs the literal and hermeneutic tradition of the biblical account; its method is aesthetic through its brief sections being like images, an assembly of different pictures of the same thing, building and unsettling the one; its aim is sensual spiritual exercise imploring/exploring the meaning of the phrase from and scene in the Gospel of John when the resurrected Jesus tells Mary Magdalene “don’t touch me.” Specifically, however, there are two themes suggesting the ‘why’ of reading this work …

Presence that is an absence ... :

How touch prohibited touch?

- Not only is this work predominately a phenomenological and deconstructive analysis of a presence that is an absence—hence evoking another example illustrative of the attempt to grasp the excess of meaning beyond the situation of an event—the precise event that it chooses to explore, the “noli me tangere” and the death and resurrection of Jesus, are identically evocative of the previous explorations we have read.

- “Noli me tangere” … “Do not touch me” … the phrase is provocative. Not only is a command, it is a prohibition, and a sensitive one: a prohibition about touch. While provocative, it is not explicitly evocative of Christianity--as Nancy points out, it is not explicitly religious, unless one reads it in the genre of discourse of Christianity, at the moment in the Gospel of John, the event of the death and resurrection of Jesus. Hence, it is a phrase doubly provocative: provocative in secular and in religious genres of discourse; provocative because it is evocative of meaning far beyond the literal situation of its phrase universe.

- This asks us to rethink the Christian narrative—consider Lyotard’s characterization of the Christian narrative of love as the most binding and totalizing narrative (the one most successful at overcoming differends); in contrast, Nancy asks us to consider the Christian narrative as a parable of parables.

- At this one parable within Christianity, at this one moment in the Gospel of John, we find the one parable as illustrative of all the parables, and there is a further double provocation: from the event of the death and resurrection and from the utterance of the phrase.

- From the event: the event is the death and resurrection of Jesus—this is, itself, incommensurate (death and life are an either/or, but here a both/neither)—and a moment of incommensurability that is definitive of Christianity. Midway through the story of Christianity (between the miraculous birth of Jesus and his second coming), there is this death and resurrection; without this point, there would be no story.

- From the phrase Noli me tangere: spoken by Jesus to Mary Magdalene before his empty tomb is also a moment of incommensurability: Christianity is the religion of touch (Hoc est corpus meun); at this singularly defining, constitutive moment, is Jesus’ singular prohibition of touch.

- (Compare Lyotard’s differend, Derrida’s third term of khora, and this double paradox of Christianity.)

How touch prohibited touch?

- The Noli me tangere touches us—it is provocative—by its prohibition of touch, it touches us. The phrase and the event for the phrase indicate a place or site of a dimensionless gap that separates what is brought together, to touch upon each other, in touch: touch/untouchable as a constitutive structure of sacrality.

- The touch of the prohibition of touch is incommensurable, hence cannot be understood in a cognitive registrar (genre of discourse). It must be made sensible according to an idea of sense that is as much listening (sensible perception) as it is hearing (understanding sense).

- Hence, we must consider Christianity as not a given, totalizing narrative, but as a parable of parables. Parables, though, are only heard by those who have the disposition already to hear them.

Title & Subtitle:

Noli me tangere: Latin, “don’t touch me,” said by Jesus to Mary Magdalene after his resurrection (John 20:17). Greek origin: mē mou haptou, “stop holding on to me,” “cease clinging to me,” “don’t hold me back,” “don’t stop me.”

On the Raising of the Body: Literal translation of the French “la levee du corps,” figuratively meaning “funeral,” in the sense of the ‘raising’ of a corpse from the mortuary to the funeral site.

On the Raising of the Body: Literal translation of the French “la levee du corps,” figuratively meaning “funeral,” in the sense of the ‘raising’ of a corpse from the mortuary to the funeral site.

Prologue: (pp.3-10)

OUTLINE OF THE PROLOGUE (pp.3-10):

I) Jesus’s life as iconography (pp.3-4)

I) Jesus’s life as iconography (pp.3-4)

- If ‘iconography’ is the images and symbols that ‘sketch out’ a subject, the telling images of something, be it an artist, place, etc. …

- Relation between image and logos? Phenomenological presentation vs. Post-Structuralist reading / interpretation? Derrida’s visibility, almost material or sensible weight, of traces of logos (e.g., mise en abyme as conceptual structure depicted as the image of the image)?

- Parable as para-, “alongside,” plus –bole, “a throwing, casting, beam, ray,” hence, a ‘throwing beside,’ or ‘juxtaposition,’ in some sense of a ‘comparison’ …

- Alternative to Lyotard’s ‘primitive’/‘Nazi’ narrative totalizing the community vs ‘Talmudic’ narrative as hermeneutic opening of questions? Evasion of heterogeneity of genres of discourse?

- Presentation as representation? Situation of the event’s (Ereignis, Arrive-t-il?) given? Khora as no thing, its presentation is only something in its being re-presented?

- Revelation as religious: “bringing to light a hidden reality or as deciphering a mystery” (4).

- Revelation as nonreligious: “identity of the revealable and the revealed, of the ‘divine’ and the ‘human’ or the ‘worldly.’ … of the image and the original … of the invisible and the visible” (4-5).

- Evangelical account as parable of parables: simultaneously an account given as (a) text to be interpreted, and (b) true story (since Jesus’ life is the truth the identity of (a) & (b) need to be understood by the thought of the parable itself, not by one grounded in other or as multiple);

- For those who “seeing, see not; and hearing they hear not, neither do they understand” (5); not to open eyes, but to sustain blindness;

- “The parable does not go from the image to sense: it goes from the image to a sight or to a seeing, which is either already given or not. … The parable only speaks to those who have already understood it; it only shows to those who have already seen. From the others, it hides what is to be seen, hiding even the fact that there is something to be seen” (6).

- Not that truth is for the chosen; not that a provisional vision prompts further search; but that “the parable and the presence or absence of ‘spiritual’ seeing … [are] directly or immediately correlative. There are not several degrees of figuration or literalness of sense; there is a single ‘image’ and, facing it, a vision or a blindness” (6-7).

- Not the figure-proper relation (i.e., the figurative vs. the literal); Not the appearance-reality relation (i.e., what appears to be vs. what is); Not the mimetic relation (i.e., an original vs. a copy); but an image-sight relation: seeing is sight participating in the visible and the visible participating in the invisible.

- “(The methexis in mimesis is doubtless one of the terms of the Greco-Judaic chiasmus in which the Christian invention takes shape”) (7):

- Methexis: ancient rhetoric’s theatrical act of participation (audience participates by helping to create the actions of the ritual); the relation between an instantiation and a form--cf., Derrida’s “Passions:” to analyze the rite, one must become involved in it.

- Mimesis: imitation, representation, e.g., a portrait is a representation or imitation of a person--cf., funeral oration in Lyotard’s ‘Plato Notice;’ redefinition of mimetic aspect of myth that “the presentation (Darstellung) can never be presented,” hence myth “is more of a genre of discourse whose stakes are in neutralizing the ‘event’ by recounting it, in appropriating occults mimesis as much as it attests to it” (§220).

- Chiasmus: ‘X’ structured form of argument with premise order of AB, BA (imagine the \ line of the X as As and the / line as Bs, if you trace a box around the X shape, the top moves from an A to a B, whereas the right side moves from B to an A, etc.), so, the order of the elements in a phrase or whole work will seem inverted (we’d expect AA, BB or AB, AB), e.g., “[A:] to stop [B:] too fearful, and [B:] too faint [A:] to go”—the first and last bits are parallel, with the middle bits parallel--cf., Lyotard’s peregrinations on a boat between the archipelago (between the genres of discourse) or Derrida’s methodology in On the Name: biography/questions of identity, back and forth over the abyss or the tradition’s expositions, etc.

- “(The methexis in mimesis is doubtless one of the terms of the Greco-Judaic chiasmus in which the Christian invention takes shape”) (7):

- Myths, allegories, fables, and parables all have “excesses,” but differently so;

- Parable excess is not indeterminate (like a general lesson that can go outside of itself to a universal moral); but is in its provenance or addressee (in that from which it comes or in that to which it is told);

- Cf., Lyotard’s non-agency of subject in situation of event into phrase universe;

- For parable to have meaning, must already have a capacity for its reception;

- Parable’s form as warning; says nothing to the ear that cannot hear; parable needs/waits for its listener.

- Belief assumes a sameness with the other with which it identifies and takes solace;

- Faith opens itself to being addressed by an unsettling appeal through the other thereby throwing itself into a listening to something it doesn’t know.

SUMMARY SKETCH OF THE PROLOGUE:

The life is Jesus is told in episodes (the parables of Jesus’ life); this life told about is not just a series of episodes, but his life is a parable of parables, hence, the ‘truth’ of Jesus is the image of his life—they are one and the same, his life doesn’t show a truth, it itself is the truth and the truth is inseparable from the life.

“Revelation” can be thought of as revealing a hidden mystery or identifying the image and original, but neither of these is satisfying; Nancy wants us to think a new meaning of ‘revelation’ in this identity (life-truth).

The parables are meant for those who do not know; not to make them know, but to sustain their blindness. You must already have sight to be able to see; must know how to listen in order to hear. Parables do not lead from picture to meaning or from meaning to picture; they necessitate both already and at once together. Hence, we need to think ‘parable’ as something in the relation between image and sight. (This “sight” however, must be understood as not a simple understanding linearly driven from or to an image; instead, it is a cooperatively participatory and penetrating, imitating and criss-crossing back and forth work.)

Parables, myths, allegories, and fables all have an excess, however, parable is not synonymous with any of the others. Hence, we need to figure out how the excess of the parable is different insofar as it does not point outside of itself, but is only if and because there is something already had inside.

The life is Jesus is told in episodes (the parables of Jesus’ life); this life told about is not just a series of episodes, but his life is a parable of parables, hence, the ‘truth’ of Jesus is the image of his life—they are one and the same, his life doesn’t show a truth, it itself is the truth and the truth is inseparable from the life.

“Revelation” can be thought of as revealing a hidden mystery or identifying the image and original, but neither of these is satisfying; Nancy wants us to think a new meaning of ‘revelation’ in this identity (life-truth).

The parables are meant for those who do not know; not to make them know, but to sustain their blindness. You must already have sight to be able to see; must know how to listen in order to hear. Parables do not lead from picture to meaning or from meaning to picture; they necessitate both already and at once together. Hence, we need to think ‘parable’ as something in the relation between image and sight. (This “sight” however, must be understood as not a simple understanding linearly driven from or to an image; instead, it is a cooperatively participatory and penetrating, imitating and criss-crossing back and forth work.)

Parables, myths, allegories, and fables all have an excess, however, parable is not synonymous with any of the others. Hence, we need to figure out how the excess of the parable is different insofar as it does not point outside of itself, but is only if and because there is something already had inside.

TERMINOLOGY IN THE PROLOGUE:

- p.3: Iconography: the images and symbols that ‘sketch out’ a subject, the telling images of something, be it an artist, place, etc..

- Consider the relation this creates between image and logos—hearkening the phenomenological versus Post-Structuralist debate between presentation of something versus reading or interpretation of something: is it the given itself or the structure to which we should focus our intention. However, at once, we saw that, for Derrida, there was a visibility, almost material or sensible weight, to the traces of the logos; consider the idea of the mise en abyme as a conceptual structure depicted as the image of the image, etc. Hence, the icon is a pointing beyond itself; we don’t just read it, but it is a trace of something conceptual/structural.

- p.3: Parable: a dictionary will tell you it is a story designed to give us a lesson, typically to symbolically illustrate a moral, but this definition is like those for myths, allegories, and fables, and Nancy differentiates the parable from the others on p.8; so, we have to discover what he means by parable as we read through this section, but can keep in mind the general sense that it is like a brief story, nothing epic, but a little illustration or episode, it tells/teaches/shows us something without being literal like instructions or by giving us a full, big picture, hence, keep in mind its etymology: para-, “alongside,” plus –bole, “a throwing, casting, beam, ray,” which suggests it is a ‘throwing beside,’ or ‘juxtaposition,’ in some sense of a ‘comparison,’ and that Nancy describes them aesthetically like pictures, images, illustrations.

- Consider this in comparison and contrast to Lyotard’s ideas on narratives (e.g., in his Postmodern Condition (see ~here~) or The Differend's ‘primitive’ or ‘Nazi’ narrative totalizing the community versus the ‘Talmudic’ narrative that is hermeneutic and opens questions) and the heterogeneous nature of genres of discourse forbidding translation of one into another and each having their own distinct stakes or aims (so, for Nancy, the parable for those who aren’t the disciples).

- p.3: Parabolic: like a parable, parable-like.

- p.4: What Appears: se présente, it appears by being Represented: which is se représentant; notice the word “present:” in both, a presentation is what is present, what is presented by its re-presentation.

- Consider this through ideas of the event’s (Ereignis, Arrive-t-il?) presentation that then necessitates situation into the moments of the phrase universe. Also, think of Derrida’s “Khora,” appearing as the lack midway in the Timaeus, through Plato’s telling of it, through the scholarly tradition of commentaries on it, through Derrida’s presentation of his essay on the Khora … since the Khora is no thing, its presentation is only something in its being re-presented.

- Truth: translates the Greek “aletheia” which literally means “a disclosure” and “an unconcealment,” hence, ‘truth’ is what is revealed to be the case, or, we could say, what is ‘presented.’

- However, consider this in the French philosophers following Heidegger as that revelation-concealment two-step, for that which is revealed is revealed as it recedes from us, for that which is, is a representation of the presented in its withdrawal (the creation of the recursive or the infinite copies; the always already given in advance of the giving).

- p.5: Pedagogy: methods and practices of teaching, e.g., Socrates’ pedagogy was to ask questions to promote interlocutors to realize what they didn’t know and think carefully for themselves.

- Historically/etymologically, the pedagogue was first the slave to the youth, the one who escorted and supervised the youth (the agogos being ‘leader’ to the pedo, ‘child’); later, this became ‘teacher’ of the youth. Hence, consider the idea of pedagogy as method of teaching as colored by this idea of serving and leading.

- p.6: Passivity, passion: that initiates every kind of sense; “Passions:” from the Greek pathos, that which you suffer, endure, feel; this root is the same in “passive,” meaning “capable of feeling or suffering.”

- p.7: Methexis: participation, the relation between an instantiation and a form, e.g., there is ‘beauty itself’ and then there is a ‘beautiful cat,’ the beautiful cat ‘participates’ in the idea of beauty itself.

- Consider how, in ancient rhetoric, this was a theatrical act of participation wherein the audience participates by helping to create the actions of the ritual—hence, in Derrida’s “Passions,” the attention to the scholar/analyst/spectator becoming involved in the enactment of ritual (to analyze the rite, one must become involved in it).

- Mimesis: imitation, representation, e.g., a portrait is a representation or imitation of a person.

- Consider Lyotard’s discussions of mimesis in his The Differend (see ~here~), first its power in the engagement of funeral oration (making the audience akin the dead by sharing their greatness) in the Plato Notice, then, by the final chapter, his critique of Lacoue-Labarthe’s theory of myth’s being a tool of the Nazis because of mimesis; instead, Lyotard counters: (1) The power of myth is from its “mere formal properties of the narrative tradition anchored as it is in a world of invariable names where not only the heroes but also the narrators and narratives are established and permutable, and thus identifiable respectively and reciprocally… (2) Myth can be used only as an instrument by an instance which is not narrative, mythical… (3) If ‘mimetic’ is understood as imitative or representative, then myth is not exceptionally mimetic. If mimesis signifies … that the presentation (Darstellung) can never be presented (Nos. 119, 124-27, 131), then myth—which is more of a genre of discourse whose stakes are in neutralizing the ‘event’ by recounting it, in appropriating occults mimesis as much as it attests to it” (§220).

- Chiasmus: a crossing or ‘X’ structured form of argument with a premise order of AB, BA (imagine the \ line of the X as As and the / line as Bs, if you trace a box around the X shape, the top moves from an A to a B, whereas the right side moves from B to an A, etc.), so, the order of the elements in a phrase or whole work will seem inverted (we’d expect AA, BB or AB, AB), e.g., “[A] to stop [B] too fearful, and [B] too faint [A] to go”—the first and last bits are parallel, with the middle bits parallel.

- Consider the crisscrossing method as also a movement over/through/between like the peregrinations on a boat between the archipelago (between the genres of discourse) in Lyotard’s The Differend (see ~here~) or Derrida’s work in On the Name’s essays back and forth between biography and questions of identity, back and forth over the abyss or the tradition’s expositions, etc.

- pp.8-9: Tautology: a necessarily logically true proposition, true because it repeats itself, expresses redundancy, e.g., “free gift!” is tautological because a gift, by definition, is what is given, and free means it is not bought.

BACKGROUND ON MATTHEW 13:10-17, 34-35:

Disciples ask Jesus the purpose of the parables; he replies: “to you it has been given to know the secrets of the kingdom of heaven, but to them it has not been given. For to those who have, more will be given, and they will have an abundance; but from those who have nothing, even what they have will be taken away. The reason I speak to them in parables is that ‘seeing they do not perceive, and hearing they do not listen, nor do they understand.’ With them indeed is fulfilled the prophecy of Isaiah that says: ‘You will indeed listen, but never understand, and you will indeed look, but never perceive. For this people’s heart has grown dull, and their ears are hard of hearing, and they have shut their eyes’ so that they might not look with their eyes, and listen with their ears, and understand with their heart and turn—and I would heal them’” (Mat 13:11-15).

Matthew 13:34-35 explains he told the parables to the crowds (and nothing otherwise) to fulfill the prophecy (Isaiah), and to “proclaim what has been hidden from the foundation of the world.”

So … is this the use of parables for similitude (the antique-medieval mimetic cosmological account and alchemical formula of ‘as above, so below’—hence language of life used to speak of the heavenly)? But explanation after emphasizes obfuscation; the disciples show concern for the understanding of others, Jesus expresses concern for maintaining esoteric nature of truth (i.e., disagree with commentaries that suggest this is an ‘easy’ way to teach the ‘ignorant,’ e.g.: “A parable is a shell that keeps good fruit for the diligent, but keeps it from the slothful” (Matthew Henry’s Commentary, Mat 13:1-23)).

On the Point of Departure: (pp.11-19)

OUTLINE OF 'ON THE POINT OF DEPARTURE' (pp.11-19):

- “En Partance” … en partance pour (“bound for, an imminent departure”); la partance (“the departing, the parting”)

I) Noli me tangere

- Noli scene as ‘sudden appearance within which a vanishing is played out’ (11);

- Popularity of the phrase Noli me tangere (religious only due context) (12);

- Prohibition of touch that touches; dimensionless gap separating touching-touched or touch from itself (13);

- Noli as Hapax (hapax legomenon: a word happening only once in a corpus) (14);

- Paradox of Noli me tangere and Hoc est corpus meum (“This is my body,” Jesus’ words at last supper, priest’s words at communion/sacrament of the Eucharist) (14);

- Exception? Or, Christianity as this paradox? Cf., Lyotard’s differend; Derrida’s “double oscillation;”

- Sacred always contains “untouchable,” withdrawal, distance, distinction, incommensurability;

- “Resurrection:” Greek anastasis (“rising up;” aná- (“up, again”), -histēmi (“to stand,” literal act of standing or figuratively dissension, e.g., ‘one takes a stand;’ same verb and definition as “stasis”); uprising;

- Being and truth as arisen in the slipping away; uprising as a holding firmly in a stance before death;

- Does not vanquish death; is neither return to life nor regeneration; neither dialectics nor mediation of death; not erection; not action, but a passivity (pathos).

ROUGH SKETCH OF 'ON THE POINT OF DEPARTURE':

Popularity due to ‘gap’ (pp.11-13): There is an enduring cultural/artistic popularity of the phrase Noli me tangere despite neither invoking anything explicitly religious/sacred beyond the scriptural context, nor being linguistically or idiomatically unusual. The vague context it gives (unlike what one does with similar expressions, one doesn’t necessarily wait for more information before sensing the meaning of this phrase) is like a warning before a danger. The warning “Don’t touch” touches us and cannot not touch us (makes an impact by its nature as a warning); it touches on the sensitive point of touching (seems impolite to discuss touching, something loaded with innuendo); hence, it touches on sensitivity itself (being receptive to sense, and sense itself); and sensitivity is precisely what it cannot touch (because it’s a command not to) in order to carry out its ‘touch’ (to fulfill its art, tact, grace as a warning that touches the other, makes the other heed it)—its whole point, then, is a gap, a fissure, between touching-touched-touch(itself), its point separates (don’t!) what it (touching) brings together (whole sensible chain). Hence, the popularity of the phrase can be attributed to this ‘gap’ that is intrinsic to ‘touch’ and integral to what makes the sacred be sacred--i.e., present in the sacred is always the idea of the “untouchable,” withdrawal, distance, distinction, incommensurability (the immeasurable, condition of having absolutely no criterion by which to judge a case) (pp.11-13).

Christianity and Touch: But … nothing and no one is untouchable in Christianity (e.g., even the body of God is to be drunk and eaten); it is the preeminent religion of touch, of the sensible, of the body. Hence, Noli me tangere is: either an exception, something exceptional (because at no other time does Jesus prohibit or refuse being touched); or we have to think the two phrases (Hoc est corpus meum (“This is my body,” the words Jesus spoke at the last supper and a priest speaks at communion/sacrament of the Eucharist) and Noli me tangere (“don’t touch me”)) together as a paradox; or both … an exception and a part of a paradox, hence very rich with meaning.

- Consider the “double oscillation” Derrida discusses where the Khora (etc.) are neither/nor and both/and.

Resurrection (pp.15-19): How we need to understand ‘don’t touch’ as exception and paradox is that Jesus’ presence (possibility of touching him) comes only with his departing, which means we need to understand resurrection as meaning both a rising up and as a dissension/insurrection, as an appearance in a disappearance (e.g., in discovering the empty tomb, one discovers the resurrection, or, in nothing, one sees that something has happened). Resurrection doesn’t conquer death; it is not a return to life; it is not a regeneration; instead, it is the discontinuity of another life in or of death; it is the firm stance one takes before death (the resurrection as uprising of the other in the self—it is a ‘passivity,’ a ‘passion’).

TERMINOLOGY IN 'ON THE POINT OF DEPARTURE':

- p.13: Sacrality: meaning-structure that makes up sacredness or the state/condition of being sacred.

- p.14: Incommensurability: the immeasurable, condition of having absolutely no criterion by which to judge a case. (Consider, of course, Lyotard’s differend!)

- p.14: Hapax, which is short for hapax legomenon, which means a word that happens only once in a whole corpus or body of works, e.g., at no other time does Jesus prohibit or refuse being touched.

- Hoc est corpus meum: “This is my body,” the words Jesus spoke at the last supper and a priest speaks at communion/sacrament of the Eucharist. This signals the central paradox of Christianity, for Nancy, when confronted with “noli me tangere.”

- Noli me tangere: “don’t touch me.”

- Paradox: proposition with seemingly sound reasoning that leads to absurd or contradictory conclusion; despite seeming senselessness, it may be true or may be false.

- p.15: Resurrection: from the Greek anastasis, “rising up,” be it from being seated or from the dead, from aná- (“up,” “again”) plus -histēmi (“to stand,” literally either act of standing or figuratively dissension, as when ‘one takes a stand;’ same verb that gives us the identically defined “stasis”).

- p.18: Aufhebung: German, literally, “to raise up,” but has contradictory meanings of “to abolish, cancel, annul, do away with” and “to preserve”—in Hegel’s philosophy, it is often translated as “sublation” to designate the supercession and preservation in the movement of the dialectic wherein the synthesis shows itself as the mediation, hence, has overcome the thesis-antithesis fight and also has kept elements thereof since it is precisely a moderated proposition. Nancy’s point here is that his analysis of resurrection does not spiral out as a kinda-reject-kinda-repeat of the idea of the life-death circling; instead, it is a ‘verticality’ over the ‘horizontallity’ of the empty tomb, i.e., imagine a line straight up from one flatly going side to side, the ascension of one has no side-to-side-ness about it, will never get where it goes by following the other line back and forth—so, no circle, no spiral, but a cross, a set of perpendicular lines.

- Lethe: oblivion, forgetfulness, concealment; the name of a spirit of forgetfulness, as well as the river in Hades.

mē mou haptou — Noli me tangere: (pp.20-26)

SUMMARY SKETCH OF Mē MOU HAPTOU:

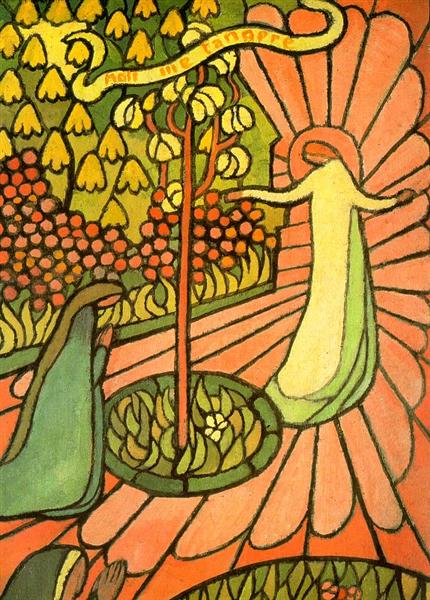

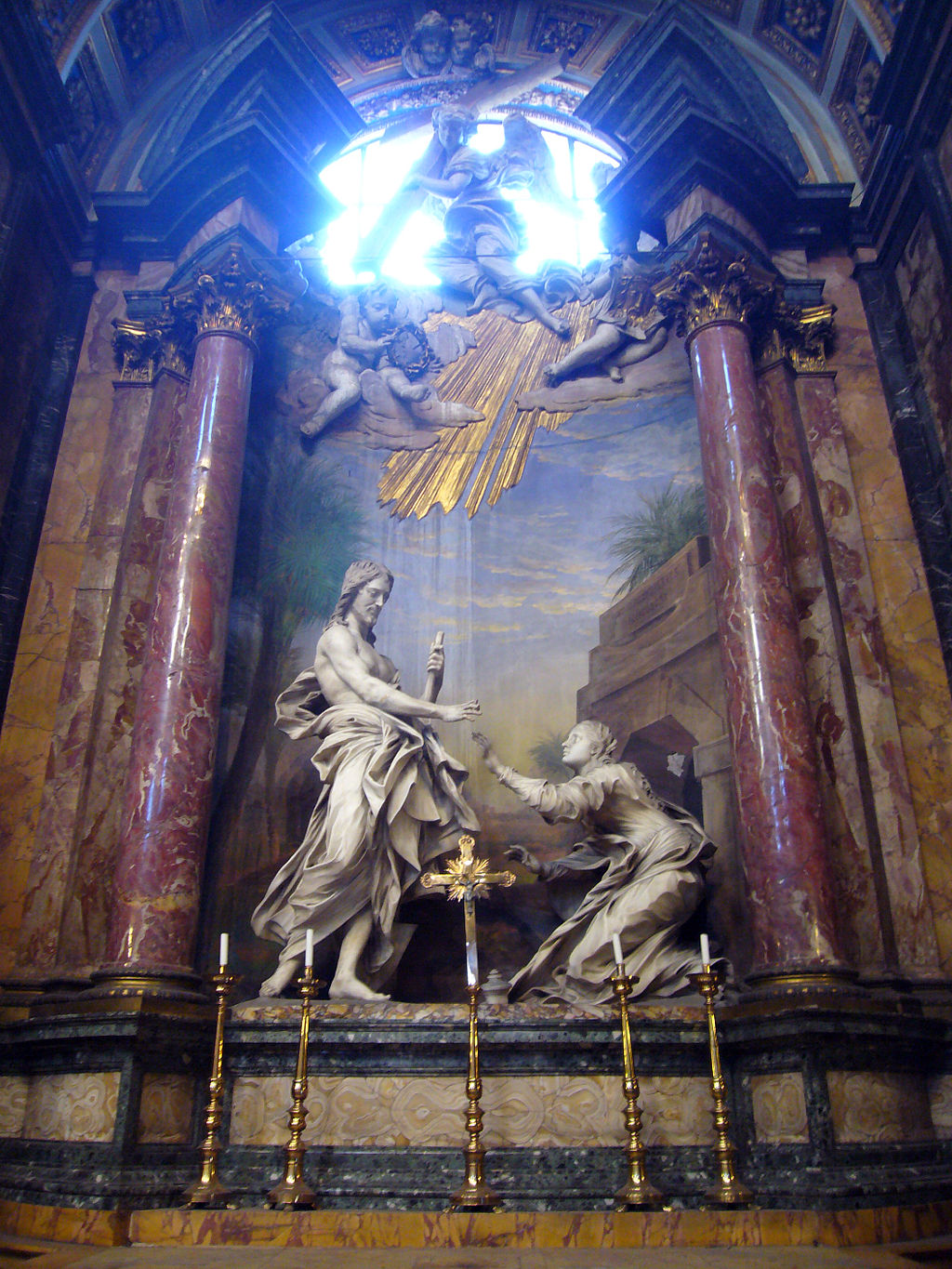

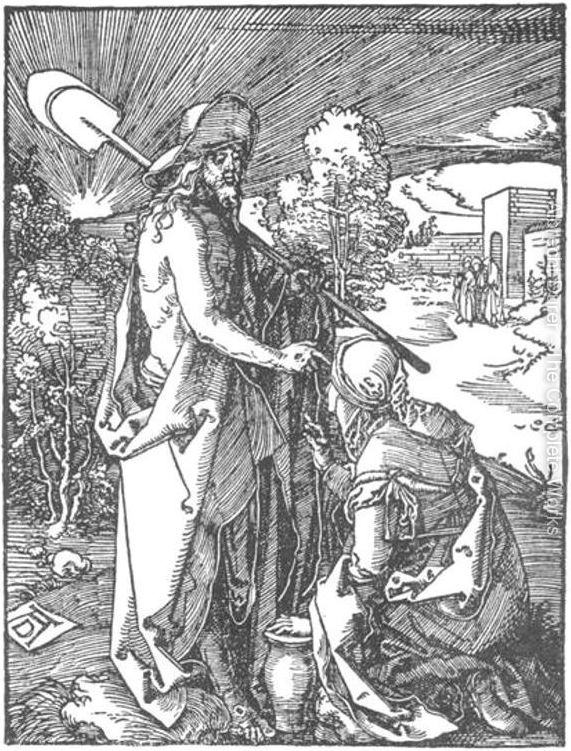

After quoting the Biblical text, Nancy discusses how it is organized around vision, then connects this to the envisioning of the scene by (most) artists, who emphasize the spectacle and miraculous, as opposed to the textual version, which emphasizes the familiar and natural. Noli me tangere, then, is deemed the most subtle and reserved scene of delicate intrigue, as revealed by Rembrandt’s painting and Dürer’s woodcut.

TERMINOLOGY:

- p.26: Apotheosis: to deify, make divine; has both theological and aesthetic senses, the latter is when art elevates figures to God-like positions or shows them as ‘God-revealed.’

- p.26: Kenosis: emptiness, self-emptying (of one’s own will, so as to become entirely receptive to God’s will).

ON JOHN 20:11-18:

Mary’s crying; for love or worry?; Seeing angels, shouldn’t this ease her?

Just two angels; watchers, sitting in repose; question why she cries, is this rebuke or concern?

Jesus answers before the angels by asking her questions;

Mary doesn’t name ‘who’ when she asks him if he has taken him away;

Jesus speaks her name, initiates her recognition; she responds by turning to him and addressing him (perhaps as a question, maybe an assertion) with the most honorable title (Rabbani, “my master,” rather than Rabbi, the title connected to Palestinian sages, or Rab, the title for the Babylonian sages, thereafter deemed to be in that order a hierarchy of honor, and also used in terms of historical ordering, the oldest given the name Rabbon—all these titles not in recorded use until around 30 c.e.)

ON REMBRANDT VAN RIJN (1606-1669, b. Leiden, d. Amsterdam):

Remained within The Netherlands, and while he studied for a short while (ca. 1624) under Pieter Lastman (history painter) and the works of European painters, his dominate form of study was direct observation of people, things, and surroundings (he later became a talented teacher of others). Prolific painter, also draftsman and print/etcher; famous for his attention to light and atmosphere in paintings (e.g., the most famous, “The Night Watch,” 1642).

“Christ and St. Mary Magdalen at the Tomb,” 1638, oil on panel, 21”x19”, Royal Collection Trust:

Note the creative choice of how he depicts the Biblical material: it is the moment of realization that just precedes Mary’s recognition of Christ (she first mistook him as the gardener, addressed him first as “sir” in Greek, then, upon recognition, “Rabbouni,” “Master,” in Aramaic, her native language) outside the empty tomb; can see the tension in their poses, especially Mary, craning her neck to see Jesus as she kneels over, having been weeping; Jesus stands precisely between the intense spot of light and dark hollow of the cave, but Mary is the visual pivot of the work.

Notable use of (dawn) light (symbolic sense of coming to know and of God, spiritual enlightenment), illuminates the towers in center background, Jesus’ back and side, the side of Mary’s face; shadows Jesus’ face, the women on far lower left, descending away from the tomb (Gospels of Mark and Luke refer to ‘three Maries’ at the tomb), and the tomb itself, dark, empty, with two angels at its side.

ON ALBRECHT DÜRER (1471-1528, b./d. Nuremberg):

Working predominately in engravings/printmaking (drypoint, woodcut; mostly religious scenes), also alter pieces, watercolors (landscapes), oils (portraits). Known for introducing classical and Italian (high Renaissance) motifs into German styles, innovations in perspective and proportion (writing various theoretical treatises on these, geometry (Four Books on Measurement), a book on city fortifications, which applies his geometry to architecture/engineering, and Four Books on Human Proportion (1528, on anatomy, movement, and aesthetics (on ideal beauty, and proposed that creating beautiful things, initially thought as inspired, was a matter of ‘selective inward synthesis’))—all using German, instead of Latin, and craftsman, instead of scholar, language). The prints are very small, cramped scenes, windows onto events, rather than sprawling paintings;

The Small [Woodcut] Passion:

set of 36 (37, if count title page) wood cuts, about 5x4” depicting Life of Christ and the Passion, as well as two images of the Fall of Man and the Expulsion from Paradise at the beginning of the set, and the Pentecost and Last Judgment at the end—the Passion, then, is the center of the series from Fall to Redemption. Designed (by him) and cut (by four people) within about two years (1508-10), published in 1511 by himself (his godfather was a successful publisher, and Nuremberg was a city full of and known for printing press publishing; published with facing pages having Latin verses by Benedictus Chelidonius); most extensive of all his series (34 blocks survive of the 36, and are held by the British Museum). (Made between his work started and ended on Engraved Passion, or Large Passion.)

#31 is “Christ Appears to Mary Magdalene,” both appear to be reaching out to touch each other

#30 Christ Appears to his Mother” and #32 “Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus” both show Christ with beams of light radiating from his head, whereas #31 has beams of light in the sky around the rising sun behind Jesus.

Like with Rembrandt’s painting, the depiction of Christ is as a slighter, sturdy, but not heroic, gardener, not a glorified deity. “Gardener” … some suggestions that how John 20 starts with a mention of it being early on the first day of the week there is a reference back to Genesis and creation, and thereby with Adam and Eve in the garden.

Working predominately in engravings/printmaking (drypoint, woodcut; mostly religious scenes), also alter pieces, watercolors (landscapes), oils (portraits). Known for introducing classical and Italian (high Renaissance) motifs into German styles, innovations in perspective and proportion (writing various theoretical treatises on these, geometry (Four Books on Measurement), a book on city fortifications, which applies his geometry to architecture/engineering, and Four Books on Human Proportion (1528, on anatomy, movement, and aesthetics (on ideal beauty, and proposed that creating beautiful things, initially thought as inspired, was a matter of ‘selective inward synthesis’))—all using German, instead of Latin, and craftsman, instead of scholar, language). The prints are very small, cramped scenes, windows onto events, rather than sprawling paintings;

The Small [Woodcut] Passion:

set of 36 (37, if count title page) wood cuts, about 5x4” depicting Life of Christ and the Passion, as well as two images of the Fall of Man and the Expulsion from Paradise at the beginning of the set, and the Pentecost and Last Judgment at the end—the Passion, then, is the center of the series from Fall to Redemption. Designed (by him) and cut (by four people) within about two years (1508-10), published in 1511 by himself (his godfather was a successful publisher, and Nuremberg was a city full of and known for printing press publishing; published with facing pages having Latin verses by Benedictus Chelidonius); most extensive of all his series (34 blocks survive of the 36, and are held by the British Museum). (Made between his work started and ended on Engraved Passion, or Large Passion.)

#31 is “Christ Appears to Mary Magdalene,” both appear to be reaching out to touch each other

#30 Christ Appears to his Mother” and #32 “Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus” both show Christ with beams of light radiating from his head, whereas #31 has beams of light in the sky around the rising sun behind Jesus.

Like with Rembrandt’s painting, the depiction of Christ is as a slighter, sturdy, but not heroic, gardener, not a glorified deity. “Gardener” … some suggestions that how John 20 starts with a mention of it being early on the first day of the week there is a reference back to Genesis and creation, and thereby with Adam and Eve in the garden.

The Gardener (pp.27-30):

SUMMARY SKETCH OF “THE GARDENER”:

Mary Magdalene mistakes Jesus for a gardener (until he speaks her name, initiates her recognition; she responds by turning to him and addressing him (perhaps as a question, maybe an assertion) with the most honorable title, Rabboni); having known him well, there must be a reason for her mistake, he must be not recognizable, or at least not immediately recognizable. Nancy proposes two possibilities that “must remain undecided:” either she has no ‘schema’ by which to recognize him (certain he is dead, she hasn’t a concept by which to think his life); or he is at first not recognizable even while he is himself (27). The “twofold significance” of the difficulties of recognition: first, he is the same without being the same (appearance of the dead as “the appearing of an appeared and disappeared” that “bears the imprint of death,” that has departure imprinted on presence); second, the stakes of faith (“entrusting oneself to the unknown”) (28). The latter issues a comparison of the faith of John (trusts the emptiness itself), Thomas (faith in formal terms, believes upon proof), and Mary (faith in neither emptiness nor proof; believes because she hears). Belief as a substitute for the known and faith as an entrusting of oneself to the unknown are exemplified in how painters use the attributes of gardeners (hats, hoes, shovels, etc.) in the scene. Mary’s faith linked to Abraham’s; their fidelity is to naming, and their responses are not spoken, but in leaving, “The response to the truth that is on the point of departure is to leave with it” (30).

Mary Magdalene mistakes Jesus for a gardener (until he speaks her name, initiates her recognition; she responds by turning to him and addressing him (perhaps as a question, maybe an assertion) with the most honorable title, Rabboni); having known him well, there must be a reason for her mistake, he must be not recognizable, or at least not immediately recognizable. Nancy proposes two possibilities that “must remain undecided:” either she has no ‘schema’ by which to recognize him (certain he is dead, she hasn’t a concept by which to think his life); or he is at first not recognizable even while he is himself (27). The “twofold significance” of the difficulties of recognition: first, he is the same without being the same (appearance of the dead as “the appearing of an appeared and disappeared” that “bears the imprint of death,” that has departure imprinted on presence); second, the stakes of faith (“entrusting oneself to the unknown”) (28). The latter issues a comparison of the faith of John (trusts the emptiness itself), Thomas (faith in formal terms, believes upon proof), and Mary (faith in neither emptiness nor proof; believes because she hears). Belief as a substitute for the known and faith as an entrusting of oneself to the unknown are exemplified in how painters use the attributes of gardeners (hats, hoes, shovels, etc.) in the scene. Mary’s faith linked to Abraham’s; their fidelity is to naming, and their responses are not spoken, but in leaving, “The response to the truth that is on the point of departure is to leave with it” (30).

The Hands (pp.31-37):

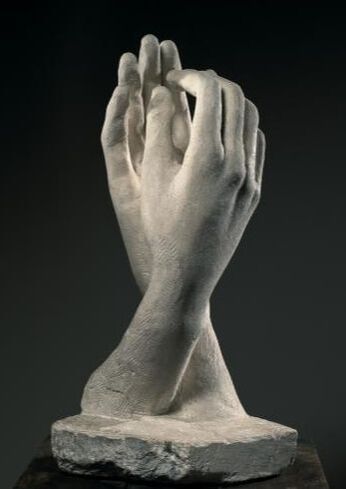

Auguste Rodin, The Cathedral, ca. 1908, Musée Rodin

Auguste Rodin, The Cathedral, ca. 1908, Musée Rodin

SUMMARY SKETCH OF “THE HANDS”:

Touch is linked to the gesture of hands; the relation can be the least intimate, peaceful, beneficent. Painters engage the game of the hands to reveal the delicacy and complexity of the scene. Hands act like an index for the arrangement and unfolding of the action and meaning of the scene. Mary’s hands indicate arrival; Jesus’ departure. However, there are also instances of touch (ambiguity of actual touch or mere occurrence on the same plane best considered intentional on the part of the artists). When there is a touch by Jesus to repel the touch of Mary, the meaning of Noli me tangere changes; the shift in its sense suggests that Jesus’ touch is the reason for the prohibition of Mary’s touch (I touch you, you do not touch me). Such is a touch that holds the other at distance:

“Love and truth touch by pushing away: they force the retreat of those whom they reach, for their very onset reveals, in the touch itself, that they are out of reach. It is in being unattainable that they touch us, even seize us. What they draw near to us is their distance: they make us sense it, and this sensing is their very sense. It is the sense of touch that commands not to touch” (37).

Further, they tell us do not even wish or desire to touch, and, if touching, forget the touch, for you must know that you hold nothing and must love this nothing; love and let go.

Touch is linked to the gesture of hands; the relation can be the least intimate, peaceful, beneficent. Painters engage the game of the hands to reveal the delicacy and complexity of the scene. Hands act like an index for the arrangement and unfolding of the action and meaning of the scene. Mary’s hands indicate arrival; Jesus’ departure. However, there are also instances of touch (ambiguity of actual touch or mere occurrence on the same plane best considered intentional on the part of the artists). When there is a touch by Jesus to repel the touch of Mary, the meaning of Noli me tangere changes; the shift in its sense suggests that Jesus’ touch is the reason for the prohibition of Mary’s touch (I touch you, you do not touch me). Such is a touch that holds the other at distance:

“Love and truth touch by pushing away: they force the retreat of those whom they reach, for their very onset reveals, in the touch itself, that they are out of reach. It is in being unattainable that they touch us, even seize us. What they draw near to us is their distance: they make us sense it, and this sensing is their very sense. It is the sense of touch that commands not to touch” (37).

Further, they tell us do not even wish or desire to touch, and, if touching, forget the touch, for you must know that you hold nothing and must love this nothing; love and let go.

ON TITIAN (ca. 1485/90-1576, b. Pieve di Cadore, moving to Venice at 10 years old)

Tiziano Vecellio, known as Titian, is one of the most highly regarded Venetian Renaissance painters. His major contributions include painting altarpieces, landscapes, portraits, and mythological works (he deemed poesie, or visual poetry); stylistically, he is most known for his diverse experimentation with styles, but fairly consistent use of intense, bold color.

His altarpieces were considered somewhat shocking, increasing the scale and intensifying color so that they could be seen from the farthest ends of the cathedrals (e.g., ‘Assunta’ in Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari in Venice); internationally famous for his portraits, these were also startling due their psychological depth and indications of status (e.g., Emperor Charles V; Pope Paul III).

Tiziano Vecellio, known as Titian, is one of the most highly regarded Venetian Renaissance painters. His major contributions include painting altarpieces, landscapes, portraits, and mythological works (he deemed poesie, or visual poetry); stylistically, he is most known for his diverse experimentation with styles, but fairly consistent use of intense, bold color.

His altarpieces were considered somewhat shocking, increasing the scale and intensifying color so that they could be seen from the farthest ends of the cathedrals (e.g., ‘Assunta’ in Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari in Venice); internationally famous for his portraits, these were also startling due their psychological depth and indications of status (e.g., Emperor Charles V; Pope Paul III).

ON JACOPO DO PONTORMO (1494-1557, b. Pontormo)

Florentine painter (mainly religious, but also portraits and mythological scenes, the latter especially when employed by the Medici family) sometimes identified as an early ‘mannerist’ for his expressive, personal style—an altarpiece in Florence’s Church of San Michele Visdomini has been described as embodying an agitated, neurotic emotionalism—which was quite unlike the popular classicism of the high Renaissance with its balance, grace, and tranquility. His style engaged brilliant colors and often entangled, swirling, overlapping composition. His mid-late (1522-25) Passion cycle was influenced by the woodcuts of Albrecht Dürer; his last works show influence by Michelangelo, which is also recorded in his diary kept during his reclusive later years.

Florentine painter (mainly religious, but also portraits and mythological scenes, the latter especially when employed by the Medici family) sometimes identified as an early ‘mannerist’ for his expressive, personal style—an altarpiece in Florence’s Church of San Michele Visdomini has been described as embodying an agitated, neurotic emotionalism—which was quite unlike the popular classicism of the high Renaissance with its balance, grace, and tranquility. His style engaged brilliant colors and often entangled, swirling, overlapping composition. His mid-late (1522-25) Passion cycle was influenced by the woodcuts of Albrecht Dürer; his last works show influence by Michelangelo, which is also recorded in his diary kept during his reclusive later years.

- Noli me Tangere, 1530’s, panel; private collection.

ON ALONSO CANO (1601-67, b. Granada, Spain)

Painter (studied under his well-known Baroque painter/brother-in-law Juan del Castillo and Francisco Pacheco, Veláquez’s teacher (Veláquez being the painter of “Las Meninas,” the example of mise en abyme re: Derrida); became royal painter), sculptor (studied under Juan Martínez Montanés, famous for realistic icons through churches in Seville), and architect (studied under his father, Miguel Cano; became royal architect). Said to have a violent temper, and suffered persecution for it; said to also have taken Holy Orders (after his wife died; for whose death he was questioned about murder) so as to avoid further persecution. However, being dubbed the ‘Spanish Michelangelo’ due his diverse talents, he was frequently welcomed back into court favor after many fleeings, chasings, etc. His painting work is known for its boldness, monumental scales, and use of darkness; his sculpture was said to be classic, elegant, expressive, and simple; his architecture is cited as having some of Spain’s most inventive and original façade work.

- Noli me tangere (ca. 1640); oil on canvas; Museum of Belle Arts Budapest.

Mary of Magdala (pp.38-43):

SUMMARY SKETCH OF “MARY OF MAGDALA”:

Mary, being Lazarus’ sister (also cf. 17-8), allows Nancy to begin the section prompting ideas justifying his earlier evaluation of Mary’s faith as unique (cf., 29-30). One idea issues from the fact that her brother was brought back from death by Jesus—though, what this prompts us to think is complex, Nancy asserts that “Thus she had already shown the kind of trust she places in her Lord” (38), which is telling because it evades telling us exactly how to interpret this … should we think that her faith is unique because she has seen the miracle … it seems so, but what is the miracle? Nancy has told us that Jesus’ resurrection is not rebirth to an old or new life; he tells us here that “she is assured that the dead brother can still rise and walk, that he has actually not ceased doing this, as do all the dead, for they all walk with the living. The dead are deceased, but as deceased, they do not cease accompanying us, and we do not cease leaving with them” (38-9). Further ideas come from the reflections on her anointing Jesus’ feet with a costly perfume. The story’s context opens the idea that her close proximity to Jesus, to what is not of this world, is the good life; its content opens ideas on perfume as unction and as an embalming done in advance. This raises ideas that are then explored in Rembrandt, Dostoevsky, and Nietzsche, and, hearkening the smell of death, prompt reflections on how sanctity must be sensed. (For truth, cf., 4, and for opening one’s eyes in the dark, cf. 19.) Finally, the idea we are left on is that the touch of sense is identical to its retreat (cf. 7, on image and sight, and 18, on stance).

Mary, being Lazarus’ sister (also cf. 17-8), allows Nancy to begin the section prompting ideas justifying his earlier evaluation of Mary’s faith as unique (cf., 29-30). One idea issues from the fact that her brother was brought back from death by Jesus—though, what this prompts us to think is complex, Nancy asserts that “Thus she had already shown the kind of trust she places in her Lord” (38), which is telling because it evades telling us exactly how to interpret this … should we think that her faith is unique because she has seen the miracle … it seems so, but what is the miracle? Nancy has told us that Jesus’ resurrection is not rebirth to an old or new life; he tells us here that “she is assured that the dead brother can still rise and walk, that he has actually not ceased doing this, as do all the dead, for they all walk with the living. The dead are deceased, but as deceased, they do not cease accompanying us, and we do not cease leaving with them” (38-9). Further ideas come from the reflections on her anointing Jesus’ feet with a costly perfume. The story’s context opens the idea that her close proximity to Jesus, to what is not of this world, is the good life; its content opens ideas on perfume as unction and as an embalming done in advance. This raises ideas that are then explored in Rembrandt, Dostoevsky, and Nietzsche, and, hearkening the smell of death, prompt reflections on how sanctity must be sensed. (For truth, cf., 4, and for opening one’s eyes in the dark, cf. 19.) Finally, the idea we are left on is that the touch of sense is identical to its retreat (cf. 7, on image and sight, and 18, on stance).

Do Not Touch Me (pp.44-48):

SUMMARY SKETCH OF “DO NOT TOUCH ME”:

This section begins and consists extensively in thinking the resurrection scene as a parable (cf., 3-10); as such, the arisen is the gardener of the garden at the tomb, and this acts as a symbol to unfold a narrative interpretation of his caring for and cultivating, which leads Nancy to theorize culture as an opening of relation to death. In this, there would be nothing to show, no last word (cf. Lyotard, Differend, §219), and that the pleasure was in the leaving. From culture, Nancy moves to the Name: here the consideration deems one leaves without leaving as something that designates (appoints) rather than signifies (indicate, mean); this reflection shows us a movement away from classic parable-thinking (which is signification, symbols for a lesson or moral), and more to some sort of Jesus-as-himself-parable, wherein such demonstration or showing of one’s message by one’s being is closer to denomination or designation of naming (cf., Lyotard, Differend, §§52, 54, on names). Finally, Nancy considers the idea of two bodies and no place. The two bodies discussion should hearken to mind the Chalcedonian Creed (ca. 451 c.e., at the fourth ecumenical council, which was convened to evaluate and select the orthodox account of Christ’s nature), which proclaimed that Jesus has two natures, one wholly human, one wholly divine, “inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably: the distinction of natures being by no means taken away by the union, but rather the property of each nature being perceived and concurring in One Person” (Chalcedonian Creed). Of course, further, this discussion of two bodies should also remind us of Nancy’s postmodernism insistence on not synthesizing dichotomies, but preserving their contrast alongside their union (e.g., his refusal to say we can decide which option accounts for why Mary did not recognize Jesus, cf., 27--i.e., it is more philosophically valuable to reap insights from both ideas, the existence of more than one idea, and the failings of certain judgment, than it is to find one as the right answer).

This section begins and consists extensively in thinking the resurrection scene as a parable (cf., 3-10); as such, the arisen is the gardener of the garden at the tomb, and this acts as a symbol to unfold a narrative interpretation of his caring for and cultivating, which leads Nancy to theorize culture as an opening of relation to death. In this, there would be nothing to show, no last word (cf. Lyotard, Differend, §219), and that the pleasure was in the leaving. From culture, Nancy moves to the Name: here the consideration deems one leaves without leaving as something that designates (appoints) rather than signifies (indicate, mean); this reflection shows us a movement away from classic parable-thinking (which is signification, symbols for a lesson or moral), and more to some sort of Jesus-as-himself-parable, wherein such demonstration or showing of one’s message by one’s being is closer to denomination or designation of naming (cf., Lyotard, Differend, §§52, 54, on names). Finally, Nancy considers the idea of two bodies and no place. The two bodies discussion should hearken to mind the Chalcedonian Creed (ca. 451 c.e., at the fourth ecumenical council, which was convened to evaluate and select the orthodox account of Christ’s nature), which proclaimed that Jesus has two natures, one wholly human, one wholly divine, “inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably: the distinction of natures being by no means taken away by the union, but rather the property of each nature being perceived and concurring in One Person” (Chalcedonian Creed). Of course, further, this discussion of two bodies should also remind us of Nancy’s postmodernism insistence on not synthesizing dichotomies, but preserving their contrast alongside their union (e.g., his refusal to say we can decide which option accounts for why Mary did not recognize Jesus, cf., 27--i.e., it is more philosophically valuable to reap insights from both ideas, the existence of more than one idea, and the failings of certain judgment, than it is to find one as the right answer).

Epilogue (pp.49-54):

SUMMARY SKETCH OF “EPILOGUE”:

Our epilogue moves from considerations of painting to seeing as a deferred touch, which allows a contrast to be built to what is true touch (wherein one must have detachment, or else it becomes a grip, not a touch), which allows us to further our ideas of how presence must give itself to be what it is, presentation, before closing back around to painting and its final revelation as a re-presentation, that it intensifies presence of an absence as absence. From here, Nancy moves the idea of the sensual and love, with Mary and John as exemplars of the former, and Christian love as an impossibility akin to the impossibility of resurrection (of course, “impossibility” not being a dismissive judgment, but the identification of it as a matter of faith, a demand for such in face of the miraculous, the incomprehensible, incommensurate, as differend; cf. 18 for holding oneself in the place of the impossible, and 13 for the idea of the ‘gap’). In closing, he uses the invocation of two lovers and two impossibles to further explore the ‘double meaning’ of the resurrection as warning and plea, as incitement and excess, concluding that double meaning is the discord at the site of the resurrection.

Our epilogue moves from considerations of painting to seeing as a deferred touch, which allows a contrast to be built to what is true touch (wherein one must have detachment, or else it becomes a grip, not a touch), which allows us to further our ideas of how presence must give itself to be what it is, presentation, before closing back around to painting and its final revelation as a re-presentation, that it intensifies presence of an absence as absence. From here, Nancy moves the idea of the sensual and love, with Mary and John as exemplars of the former, and Christian love as an impossibility akin to the impossibility of resurrection (of course, “impossibility” not being a dismissive judgment, but the identification of it as a matter of faith, a demand for such in face of the miraculous, the incomprehensible, incommensurate, as differend; cf. 18 for holding oneself in the place of the impossible, and 13 for the idea of the ‘gap’). In closing, he uses the invocation of two lovers and two impossibles to further explore the ‘double meaning’ of the resurrection as warning and plea, as incitement and excess, concluding that double meaning is the discord at the site of the resurrection.

|

“The response to the truth that is on the point of departure is to leave with it”

(Jean-Luc Nancy, Noli me tangere, 30). |

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by MacHighway