Jean-François Lyotard’s The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge

Contents:

I) A Briefest Biographical Sketch

II) Postmodernism: a Briefest Sketch

III) On The Postmodern Condition

~ ~ for Philosophy & the Arts, focus just on this last part:

IV) On "What is Postmodernism?", appendix to The Postmodern Condition

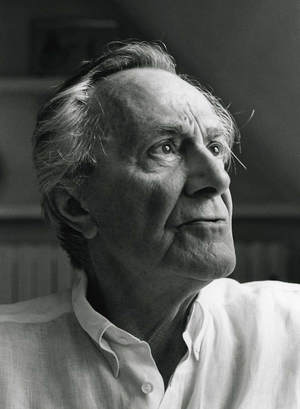

Jean-François Lyotard

“Lyotard is a demanding thinker, complex and a strain to live with.

He takes paths that are the other side of where most of us are going”

(Gary Browning, Lyotard and the End of Grand Narratives, vii.)

--Lyotard, I hazard, would have been quite pleased with this observation)

I) A Brief Biographical Sketch:

Jean-François Lyotard

(1924-1998; b. Vincennes, France; d. Paris, France).

Lyotard, in his personally reflective work Peregrinations, wrote that his earliest aspirations included becoming a Dominican monk, a painter, or a historian ...

... although, the English may be misleading, he may have wanted to be a writer of histories or histories, which is better translated as “stories,” and stories may be novels as much as the history of social science. This ambiguity is most telling. Within the every essay, “Clouds,” where he delineates these aspirations, he interrupts his own recounting of his life narrative by elaborating the two sides of what he terms “narratology,” one that embraces the disordered beauty within the orderly form of ancient narrative style, the other that is the lover of scientific rationality and insists narrative have beginning, middle, and end, and not so much disorder permitted between. Critiquing both while forging an argument about the detriment of inflexible narratives, Lyotard likens the best form to clouds that never stop changing their relation to one another and within themselves. This is helpful to keep in mind when thinking about a brief a biographical sketch--what does the narrative of one’s life do to and tell us about its object? Nevertheless ...

... With these goals—monk, painter, story-teller—he was was educated at the Paris Lycées Buffon and Louis-le-Grand, and then the Sorbonne (where he studied philosophy and literature). When the Second World War broke out, he served as a medical volunteer in the streets of Paris. He married Andrée May in 1948, with whom he had two children, Corinne and Laurence. Passing the agrégation(examination to become a teacher), he then started his teaching in 1950 at a boy’s school in Constantine, in French East Algeria, then from 1952-59, teaching military children at La Flèche. In the midst of these teaching engagements, in 1954, his environs and political activism led him to join Socialisme ou Barbarie, a socialist revolutionary organization (see info here and here). For about fifteen years, his life was one of devotion to far-left political thought and action. In 1964, a political splintering of the organization led Lyotard and his friend Pierre Souyris to join the break-away group Pouvoir Ouvrier (see info here and here). Just two years later came his resignation from official political membership, his break from faith in the efficacy of Marxist-led theory and practice, and his dedicated recommitment to the full breadth of philosophical study and writing.

Into the mid 1960’s he assisted teaching at the Sorbonne and then took a full position Université de Paris X, Nanterre--exercising his political activism in the “May 1968” political movement (see info here and here and here). Around this time, he engaged study of Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalysis, and also earned his doctorat d’état for his manuscript Discours, figure. In the late 1960’s he engaged a research position at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, and then, in the early 1970’s, a position at Université de Paris VIII, Vincennes, which he held for almost 20 years, during which he became a celebrated teacher, wrote voraciously, established his name (publishing his most famous work, The Postmodern Condition in 1979 (see info here and a copy of the text here)), and lectured worldwide (especially at University of California Irvine, San Diego, Berkeley, Johns Hopkins, Yale, Emory, University of Minnesota, Université de Montréal, Universidade de São Paulo). In the early 1990’s, he married his second wife, Dolorès Djidzek, with whom he had a son, David, in 1993. In April of 1998, in Paris, he died of leukemia.

Other Voices on Lyotard:

(1924-1998; b. Vincennes, France; d. Paris, France).

Lyotard, in his personally reflective work Peregrinations, wrote that his earliest aspirations included becoming a Dominican monk, a painter, or a historian ...

... although, the English may be misleading, he may have wanted to be a writer of histories or histories, which is better translated as “stories,” and stories may be novels as much as the history of social science. This ambiguity is most telling. Within the every essay, “Clouds,” where he delineates these aspirations, he interrupts his own recounting of his life narrative by elaborating the two sides of what he terms “narratology,” one that embraces the disordered beauty within the orderly form of ancient narrative style, the other that is the lover of scientific rationality and insists narrative have beginning, middle, and end, and not so much disorder permitted between. Critiquing both while forging an argument about the detriment of inflexible narratives, Lyotard likens the best form to clouds that never stop changing their relation to one another and within themselves. This is helpful to keep in mind when thinking about a brief a biographical sketch--what does the narrative of one’s life do to and tell us about its object? Nevertheless ...

... With these goals—monk, painter, story-teller—he was was educated at the Paris Lycées Buffon and Louis-le-Grand, and then the Sorbonne (where he studied philosophy and literature). When the Second World War broke out, he served as a medical volunteer in the streets of Paris. He married Andrée May in 1948, with whom he had two children, Corinne and Laurence. Passing the agrégation(examination to become a teacher), he then started his teaching in 1950 at a boy’s school in Constantine, in French East Algeria, then from 1952-59, teaching military children at La Flèche. In the midst of these teaching engagements, in 1954, his environs and political activism led him to join Socialisme ou Barbarie, a socialist revolutionary organization (see info here and here). For about fifteen years, his life was one of devotion to far-left political thought and action. In 1964, a political splintering of the organization led Lyotard and his friend Pierre Souyris to join the break-away group Pouvoir Ouvrier (see info here and here). Just two years later came his resignation from official political membership, his break from faith in the efficacy of Marxist-led theory and practice, and his dedicated recommitment to the full breadth of philosophical study and writing.

Into the mid 1960’s he assisted teaching at the Sorbonne and then took a full position Université de Paris X, Nanterre--exercising his political activism in the “May 1968” political movement (see info here and here and here). Around this time, he engaged study of Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalysis, and also earned his doctorat d’état for his manuscript Discours, figure. In the late 1960’s he engaged a research position at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, and then, in the early 1970’s, a position at Université de Paris VIII, Vincennes, which he held for almost 20 years, during which he became a celebrated teacher, wrote voraciously, established his name (publishing his most famous work, The Postmodern Condition in 1979 (see info here and a copy of the text here)), and lectured worldwide (especially at University of California Irvine, San Diego, Berkeley, Johns Hopkins, Yale, Emory, University of Minnesota, Université de Montréal, Universidade de São Paulo). In the early 1990’s, he married his second wife, Dolorès Djidzek, with whom he had a son, David, in 1993. In April of 1998, in Paris, he died of leukemia.

Other Voices on Lyotard:

Lyotard is “something of an anomaly. Lyotard has, in a number of respects, remained on the margins of an orthodoxy which defined itself precisely in terms of its focus on, and celebration of, the marginal.”

--Peter Dews, “Review: The Letter and the Line: Discourse and Its Other in Lyotard,”

Diacritics 14, 3: Special Issue on the Work of Jean-François Lyotard (1984): 39-49, 40.

Lyotard was “a polymath of a special sort. … A philosopher steeped in phenomenology, a militant for pluralist thinking, an esthetician of the figural, Lyotard staked out territories for innumerable scholars in literature, the arts, politics, and ethics, as well as in more recently recognized fields such as gender studies and postcolonialism.”

--Robert Harvey and Lawrence R. Schehr,

“Editor’s Preface,” Yale French Studies 99 (2001): 1-5, 1.

“at first sight, [Lyotard’s oeuvre is] more remarkable for its shifts and breaks than for any continuity,” but it is also not entirely discontinuous.

--Geoffrey Bennington, Lyotard: Writing the Event

(New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), 1.

“in every subject he took on, in all these heterogeneous projects, Lyotard was interested in what resists within them and in the dangers of resisting and thus concealing this heterogeneity and this resistance.”

Michael Naas, “Lyotard Archipelago,” Minima Memoria: In the Wake of Jean-François Lyotard,

ed. Claire Nouvet, Zrinka Stahuljak, & Kent Still (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007), 176-96, 180.

II) Postmodernism: A Brief Sketch:

Lyotard’s Postmodernism strikes a peculiar balance between the two (seemingly) conflicting schools of phenomenology and post-structuralism by taking some of each.

- Phenomenology: its basic principle is that the world gives itself to us as we give ourselves to the world, and in & by that cooperative co-givenness, meaning is constituted. Phenomenology therefore attempts to give a direct description of our lived experience as it is in itself without biases from historical, psychological, or scientific modes of thinking. Instead, each of these perspectives is acknowledged as a single mode among many by which to experience and describe the world (an acknowledgement that helps us to realize the perspectival nature of experience). Phenomenology’s fundamental method concerns the lifting of our Natural Attitude (the everyday, automatically directed along through pre-given frameworks of intentional relations by which one naturally accords independent existence to these correlates of consciousness or things intended—like when you wake up and turn off the alarm and roll out of bed without thinking about anything other than that, precisely) by the epoché, a bracketing of biases that initiates us into the Phenomenological Attitude (wherein I become aware of the intentional relation in and through which the objects are posited as such, a shifting of my attention from doing the waking up to thinking about the relation in which the alarm and I stand, it is a mode of reflection without bias, I do not think of the clock as a mechanical object that tracks time, but how it calls to me and how I obey it, etc.); within the phenomenological attitude, our aim is to describe the direct contents of consciousness concerning lived experience and the dynamic nature and construction of meaning.

- Post-Structuralism: the primarily French theory and school from the 1960’s and 70’s that is arguably a continuation &/or critique of Structuralism: which essentially argued that meaning is structured and given to us by our involvement in language/society (not just reality itself), and, in order to understand culture’s many facets, one must grasp them in regards to their relationships to and in an overarching system or structure of meaning, which is also a structure of power; its study, then, seeks to lay bare these structures and understand their effects on the deepest levels of human thought, feeling, and action. Post-structuralism’s guiding premise builds from this to argue the structure is not in nature itself, but that our minds impose this structure upon reality, forms reality in accordance with it, thus, both reality and the structures that explain reality are mental products. Surface Structures are reality’s more blatant structures, of which we can become more explicitly conscious, especially by coming to understand the unconscious’ Deep Structures. Like structuralism, post-structuralism believes that myths (traditional and in popular culture) are a predominate form of expression wherein these structures can be discovered, but furthers this to look at the full archives of human creation that range from literature to slang, architectural practices to habituated bodily movements of individuals to crowds to traffic, legal records to media to visual and audible arts, etc., etc.. A post-structuralist goal is to practice applying insights from structural recognitions and the attempt to reveal &/or undo the structures, i.e., an explicit move from theory (identifying structures) to practice (critiquing and thereby destabilizing them).

Lyotard’s work embraces the method of phenomenology, and, like post-structuralism, acknowledges the power of the “grand narratives” that we live under and how they define our thought and being. This blend is postmodernism.

“A work can become modern only if it is first postmodern.

Postmodernism thus understood

is not modernism at its end

but in the nascent state,

and this state is constant”

(Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge,

trans. Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002), 79).

“The postmodern would be that which, in the modern,

puts forward the unpresentable in presentation itself;

that which denies itself the solace of good forms,

the consensus of a taste which would

make it possible to share collectively

the nostalgia for the unattainable;

that which searches for new presentations,

not in order to enjoy them but in order to impart

a stronger sense of the unpresentable”

(Ibid., 81).

... thus ... the postmodern is not the period following the modern, nor is it an overturning or out doing of the modern. A lot of contemporary sources talk about the postmodern as being the overturning of the modern by interrupting linearity through an eclecticism (Lyotard remarked such is characterized as wearing Parisian perfume in Tokyo while eating at a MacDonald’s—this is not postmodern, this is just bad taste).

Lyotard prefers the name “re-writing modernity.”

It is primarily methodological, anti-historicism, and actively seeks to uncover biases of grand narratives. “Grand narratives” are the powerful stories that we call upon to create and structure meaning and, often, to rally people; they are the overarching organizational categories that may conjure national identity, portray capitalist political economy, invoke proletariat struggle or emancipation from marginalization, and are often captured like clichés or catch-phrases, e.g.: ‘power to the people,’ ‘as American as apple pie,’ ‘live free or die,’ ‘we are all God’s creatures,’ ‘class struggle,’ etc.. For postmodernism, all knowledge has become narrative; knowledge is a structuring force or power, not a mere label, but affective creation and direction of meaning/reality. Within this excess of narratives, narrativity itself, the rules and operation of this knowledge-cum-narrative system, and specific, especially strong grand narratives are what postmodernism targets to lay bare.

Postmodernism, then, is critique that constantly turns back to the canon (widely conceived) and takes it up and works through it to see many alternate narratives therein. It does not draw rigid boundaries between disciplines or schools of thought. It is therapeutic. It seeks to lay bare what remains unsaid.

In a letter written in the early 1980s, Lyotard describes the postmodern’s presentation of the unpresentable as one:

Lyotard prefers the name “re-writing modernity.”

It is primarily methodological, anti-historicism, and actively seeks to uncover biases of grand narratives. “Grand narratives” are the powerful stories that we call upon to create and structure meaning and, often, to rally people; they are the overarching organizational categories that may conjure national identity, portray capitalist political economy, invoke proletariat struggle or emancipation from marginalization, and are often captured like clichés or catch-phrases, e.g.: ‘power to the people,’ ‘as American as apple pie,’ ‘live free or die,’ ‘we are all God’s creatures,’ ‘class struggle,’ etc.. For postmodernism, all knowledge has become narrative; knowledge is a structuring force or power, not a mere label, but affective creation and direction of meaning/reality. Within this excess of narratives, narrativity itself, the rules and operation of this knowledge-cum-narrative system, and specific, especially strong grand narratives are what postmodernism targets to lay bare.

Postmodernism, then, is critique that constantly turns back to the canon (widely conceived) and takes it up and works through it to see many alternate narratives therein. It does not draw rigid boundaries between disciplines or schools of thought. It is therapeutic. It seeks to lay bare what remains unsaid.

In a letter written in the early 1980s, Lyotard describes the postmodern’s presentation of the unpresentable as one:

“which refuses the consolation of correct forms …

and inquires into new presentations--

not to take pleasure in them

but to better produce the feeling

that there is something unpresentable.”

--Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Explained to Children: Correspondence 1982-1985,

trans. Julian Pefanis & Morgan Thomas (London: Turnaround, Power Institute of Fine Arts, 1992), 24.

III) On The Postmodern Condition (1979)

- Jean-François Lyotard. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Translated by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, Theory and History of Literature, Vol. 10, 2002. A Translation (published in 1984) of La Condition postmoderne: rapport sur le savoir. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1979.

This work, his most well known in the United States, explores the impact of the rapid growth and influence of technology on humanity and is centrally concerned with defining the postmodern as that which, in the modern, shows the unpresentable in presentation itself.

“In the immediate aftermath of its publication, it served as a cultural signpost

pointing towards the postmodern and away from modernity”

(Gary Browning, Lyotard and the End of Grand Narratives

(Cardiff, England: University of Wales Press, 2000), 21).

Textual Analysis:

§6: The Pragmatics of Narrative Knowledge:

Definitions:

Four Aspects of Traditional {mythic} Narrative Knowledge:

Three Key Imports re: Narrative Knowledge:

Definitions:

- Knowledge: “is not only a set of denotative statements … It also includes notions of ‘know-how,’ ‘knowing how to live,’ ‘how to listen’ …, etc. … Knowledge, then, is a question of competence that goes beyond the simple determination and application of the criterion of truth, extending to the determination and application of criteria of efficiency (technical qualification), of justice and/or happiness (ethical wisdom), of the beauty of a sound or color (auditory and visual sensibility), etc.” (PMC, 18).—i.e., ‘knowledge’ as the broadest genus, species of which include science, myth, protocol, taste, etc.; includes far more than mere information, more so how to think, to live, to be the human creatures we are.

- Learning: “is the set of statements which, to the exclusion of all other statements, denote or describe objects and may be declared true or false” (PMC, 18).—i.e., ‘learning’ in a restrictive sense of the right or wrong statements that name or describe things.

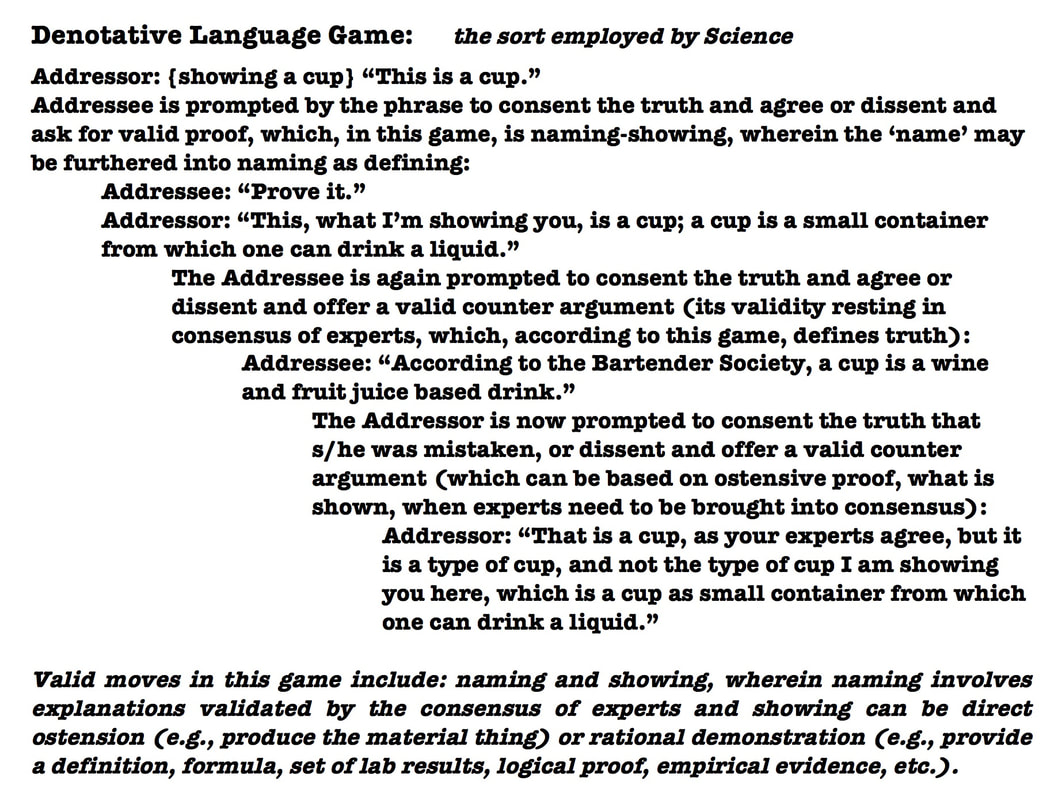

- Science: “is a subset of learning. It is composed of denotative statements, but imposes two supplementary conditions on their acceptability: the objects to which they refer must be available for repeated access, in other words, they must be accessible in explicit conditions or observation; and it must be possible to decide whether or not a given statement pertains to the language judged relevant by the experts” (PMC, 18).—i.e., the specific language game made up of denotative statements (addressor ‘names’ and ‘evidences’ X, addressees can agree, or not and therefore disagree by proposing another ‘name’ and ‘evidence’ of X, and there will be those most authorized to judge the truth of name A or B).

- Custom: “the relevant criteria (of justice, beauty, truth, and efficiency respectively) accepted in the social circle of the ‘knower’s’ interlocutors. The early philosophers called this mode of legitimating statements opinion [doxa]. The consensus that permits such knowledge to be circumscribed and makes it possible to distinguish one who knows from one who doesn’t (the foreigner, the child) is what constitutes the culture of a people [Bildung]” (PMC, 19).--i.e., custom is all the habituated preferences formative of a culture

Four Aspects of Traditional {mythic} Narrative Knowledge:

- (1) Stories recount positive or negative apprenticeships--i.e., tell of the hero’s successes or failures, which can (a) bestow legitimacy on the social institutions (the function of myths), e.g., prove our political system as best, or (b) represent positive or negative role models (the successful hero or unsuccessful one) for integration into established institutions (legends or tales), e.g., Jill successfully completed her mission to get lunch, just as Jillian had long ago successfully completed her mission to establish banquet halls across our nation, thus we should all try to be like Jill/Jillian.

- (2) Narrative works in a great variety of language games--i.e., narrative knowledge is so incredibly successful because it can incorporate the greatest number of types of speaking, therefore merge the different worlds of reality that accompany these different discourse types, e.g., Jill, who was just as brave as Jillian (evaluative statement), walked through Inman’s twisting hallways and braced herself for the humidity outside its front doors (denotative statements), for she knew she must succeed in getting a healthy lunch (deontic [duty-based] statement); nb., unlike scientific narrative, which would not allow such evaluation without a proof that could be evidenced, mythic narrative can merge scientific information with culturally based evaluations to promote ethical commands.

- (3) Transmission of narratives obeys its intrinsic ‘double pragmatic’ rule--i.e., narrative contains within itself its own rule for how it is to be transmitted, and this pragmatic, this rule for use, has two powers: it dictates all parties, and it obliges all parties. There are multiple ‘doubles’ seen in both the dictation and obligation narrative enacts.

- In the dictation of parties, the tale’s narrator is authorized to be the narrator because she has already heard the tale (been the narratee), i.e., hearing the tale (as narratee) dictates she is now allowed to be a teller of the tale (its narrator: to hear is to become a (possible) narrator. The ‘double’ here being that how the narrator is authorized as narrator is to authorize the narratee as authorized narrator. A second ‘double’ herein is that in addition to the flow of the listener becoming the next teller, there is an unification of the culture’s times into the whole flow of time: stories have been told for millennia, but really there is just one story told forever—imagine each like a single text making up a multi-volume set of that culture’s history: the set is the history, it is one thing, thus every different text making it up is really just the one history retelling itself in moments comprising the whole. There is a final double in this first power of dictating parties in the sense of bringing the first two points (with their doubles) together: the naming of the narrator in the culture made by the mythic narrative is doubly grounded by the first point (narrator was a narratee; narratees will be narrators) and the second (by being the named one in one story, which is to be the universal one the whole history tells—this makes one the “diegetic reference of other narrative events,” i.e., ‘diegesis’ is the plot told by a narrator, so just as the teller A tells story of B, her listeners C will tell the story of A who told the story of B, etc.: hence A becomes a part of the story).

- The obliging of parties follows from what the first power shows: these ‘doublings’ necessitate (e.g., if one is authorized, one’s telling authorizes others); hence “The knowledge transmitted by these narrations … determines in a single stroke what one must say in order to be heard”—and one IS NOT, unless one is heard—“what one must listen to in order to speak”—and one is not, unless one speaks—“and what role one must play … to be the objective of a narrative”—and one is not part of the history unless one is in the history, which means one must hear and tell the history, and if one is not part of the history, one simply doesn’t exist in that reality at all. All parties are obliged to perform the speech acts the narrative tradition dictates, or else they are not members of that history, which means they are not at all. Hence, narrative knowledge doubly: forms ‘knowledge’—the complete “know-how,’ ‘knowing how to live,’ ‘how to listen’” (PMC, 18, 21)—and describes how the community’s self and environmental relations play out—i.e., establishing and being the social bond.

- (4) Narrative has an unique effect on time: it follows a rhythm that preferences meter over accent that both breaks our collective remembrance and reincarnates every past and future in the present, hence never allowing a forgetting--i.e. its preference of meter is one of the sound and intuitive sense, instead of the sense as logical meanings (akin to nursery rhymes: they use sing-song nonsense, yet impart meanings); its breakage of collective remembrance is by its ability to fragment (granted by its use of sound over logic), so that these fragments can surface totally ‘out of place’ without alerting our alarm (e.g., a politician today can invoke ‘apple pie’ instead of answering a policy question, the mythic imagery conjures patriotism of some vague early republic sentiment, despite the fact that neither was relevant to the immediate question he received, nor is it true scientifically that apples originate in America); finally, its reincarnation forever in the now is that every retelling is rehearsing the past, incorporating the present, predicting the course of the future all in the now which makes the culture eternal (refuses any end, for there is always a new story, and blurs any beginning to history, as the story is always ever beginning) and universal (everyone in the culture hears the history, tells the history, becomes part of the history, there is no one outside the history, for any possible outsider is part of the story the moment their existence is noted), as it is always ever happening in the moment of telling: an everyone-forever-now.

Three Key Imports re: Narrative Knowledge:

- (1) Narrative “betokens a theoretical identity between each of the narrative’s occurrences” (PMC, 22).

- (2) Narrative Culture has “no more need for special procedures to authorize its narratives than it has to remember its past” (PMC, 22).

- (3) There is a ‘differend,’ “an incommensurability,” between Narrative knowledge and Scientific knowledge concerning ‘Legitimation’ (PMC, 23).

§7: The Pragmatics of Scientific Knowledge:

Three Aspects of Scientific Knowledge’s Research Game:

- (1) Addressor: should speak the truth (i.e., (a) provide proof, (b) refute counter arguments)

- (2) Addressee: gives or refuses assent to addressor’s assertion, thereby becomes equal to the addressor insofar as becoming a potential addressor him/herself.

- (3) Referent should be expressed in accord with what it is—this is the rule of adequation, but is what becomes a problem in this language game, for it initiated the challenge ‘what proof is there for the given proof of X?’ The solution science comes up with for this is two rules (called the rules of verification or falsification):

- (1) (dialectic rule) referent must be susceptible to proof, and is also thereafter valid as evidence;

- (2) (metaphysic rule) referent cannot give a plurality of inconsistent proofs.

Three Aspects of Scientific Knowledge’s Teaching Game:

- (1) Addressee has X to learn from Addressor

- (2) Addressee can learn X and become equal to Addressor

- (3) There are legitimate statements yielded by research that can be translated from A1 to A2 as sufficient in themselves (i.e., ‘truths,’ ‘first principles’).

Five Comparisons Between Narrative & Scientific Knowledges:

- (1) Science only allows denotative phrases; the learned are judged as such based on their ability to produce denotative, evidence-able statements.

- (2) Science does not forge the social bond; however, it is an indirect part of it, and this is the cause for problems.

- (3) Competence only concerns the addressor

- (4) Science phrase only validated by argument and never secure from future falsification

- (5) Science implies diachronic temporality as cumulative; rhythm of accent and meter are variable

Two Reasons Why we Should Examine Narrative & Scientific Knowledges:

- (1) Narrative knowledge and Scientific knowledge language games yield ‘differends’ (clash of realms incommensurate to one another so that no rule of judgment is applicable and fair)

- (2) Narrative knowledge accepts the language game of science; Scientific knowledge does not accept the language game of narrative—the latter’s rejection means it views narrative as “savage” and yields imperial impulses.

§7’s last four paragraphs elaborate two insights as reasons why the natures of Mythic & Scientific knowledges Lyotard is examining are so important: (1) the narrative (mythic) language game and the scientific language game yield a differend--i.e., they are incommensurate language games, their rules make their combined usage or interplay impossible; (2) the narrative (mythic) language game accepts the use of scientific knowledge within it, but the scientific language game rejects the legitimacy of the narrative game, instead, it views narrative as savage, and its rejection plus evaluation inspires/fuels the imperial impulse. The imperialism of the scientific language game is unique: “it is governed by the demand for legitimation” (PMC, §7, p.27).

§§8-9 thus must explore the problem of legitimation in more detail.

§8: The Narrative Function and the Legitimation of Knowledge:

Scientific Knowledge’s “problem of legitimation” is “legitimated as a problem” (27)--i.e., the problem of (concern for) valid legitimation of knowledge becomes the main issue within and for Science. Its solution to this problem used to be the reaching outside of itself and into the realm of Narrative Knowledge for the grounding of its legitimacy—and this impulse to turn to narrative for help is not gone, and may well be an inevitable recourse.

We see this from the very beginning of the Scientific Knowledge: in Socratic elenchus (its dialectic, “The game of dialogue, with its specific requirements” (28)), e.g., The Allegory of the Cave in Plato’s Republic, bks. 6-7, etc.—“each of the dialogues takes the form of a narrative of scientific discussion” (29)—and, thus, “The fact is that the Platonic discourse that inaugurates science is not scientific, precisely to the extent that it attempts to legitimate science,” which affirms that: “Scientific knowledge cannot know and make known that it is the true knowledge without resorting to the other, narrative, kind of knowledge, which from its point of view is no knowledge at all” (29).

Lyotard then delineates how Ancient and Medieval philosophy and Classical science all take recourse to narrative for validity. (Otherwise, it would have to admit to begging the question or proceeding on prejudice.)

Then, with Modern science, two new features appear:

- (1) it declares that proof of its proofs are immanent to the language game of science, and

- (2) that legitimation comes from the consensus of experts within its community (29).

As science gains this internal ground of verification, narrative undergoes its own resurgence for validating authorities, that is providing the solution for legitimation in the socio-political realms.

Then, science’s new internal operating procedures combine with the socio-political’s new methods of legitimation to yield our public realm’s method of authorization as parallel to the scientific so that ‘The People” are now the parallel experts whose consensus validates its workings and the method is by deliberation (30). As “The People” gain this authority, they destroy the social realm’s old narrative model of legitimation (i.e., destroying traditional knowledge and deeming the tradition’s ‘people’ as minorities or potential separatists who aim to spread obscurantism).

As the socio-political adopts its parallel model of the sciences, a strong, integral link is forged between the state and science. The state’s ‘people,’ however, are not content with just knowledge—they legislate. To do so, they must have recourse to narrative, and thus they render Science in Narrative Form … this can take two routes:

- (1) Cognitive (re: knowledge, aka the philosophic), or

- (2) Practical (re: liberty, aka the political and humanist).

§9: Narratives of the Legitimation of Knowledge:

The Two Routes the Science-in-Narrative-Form can take:

- –The Political: Practical (re: liberty, aka the political and humanist)

- “humanity as the hero of liberty” (31)

- “All peoples have a right to science” (31)

- Emphasis: Primary Education (deemphasize higher education)

- Because: education is breeding ground for state officers and civil managers—nation as a whole will win freedom due spread of new domains of knowledge

- State resorts to narrative of freedom when it must take control of education of ‘the people’ for the good of the progress of the ‘nation’

- –The Philosophic: Cognitive (re: knowledge, aka the philosophic, esp. re: University of Berlin 1807-10)

- Emphasis: Higher Education

- Science, for its own sake … but … as geared to the spiritual and moral training of the nation

- How get the people interested in knowledge?, by emphasizing character & action

- However, ‘science for its own sake’ and ‘for the betterment of the nation’ are phrases belonging to two incommensurate language games: the denotative & the prescriptive … So, Humboldt must unify these games, blur over their irreconcilability, or else his system won’t work … thus, he invokes: Spirit/Life animated by three interrelated aspirations:

- (1) “that of deriving everything from an original principle (corresponding to scientific activity)”

- (2) “that of relating everything to an ideal (governing ethical & social practice)”

- (3) “that of unifying this principle and this ideal in a single Ideas (ensuring that the scientific search for true causes always coincides with the pursuit of just ends in moral and political life)”

- ––these three aspirations constitute the legitimate subject (33).

- Humboldt grounds these aspirations in the German “intellectual character,” thus borrowing a theme of the political narrative, hinting at an additional unification (their ‘route’ also bears an idea of the first ‘route’) (33). However, this ‘people’ is not Germans, is not ‘the people,’ but is “the speculative spirit” (33).

- The University’s function, then, is to open all the body of learning and expound both the principles and foundations of all knowledge. The discourse on the legitimation of this scientific discourse is SPECULATION.

- The university is speculative, aka, philosophical; philosophy must restore the unity to learning (disciplines had been isolated apart; it must reunify them), link all the different sciences into this one path “as moments in the becoming of spirit” (33)—that is, to link them all in a rational narration: a metanarrative (33).

- In order to develop this ‘goal’ and ‘reason’ of science—Spirit—philosophic knowledge has taken recourse to narrative knowledge … “But what it produces is a metanarrative” (34):

- “The narrator must be a metasubject in the process of formulating both the legitimacy of the discourses of the empirical sciences and that of the direct institutions of popular cultures. This metasubject, in giving voice to their common grounding, realizes their implicit goal” (34).

- This spread throughout Europe and especially the U.S.A.

- Learning & Research are not just useful, but knowledge is validated as valuable in itself as promoting the life of the spirit—that which transcends an individual use and becomes useful in the entire journey of the spirit of life (34-35).

- True knowledge herein is “always indirect knowledge”—it is founded and becomes part of the metanarrative of a subject—life of the spirit—that therefore guarantees their legitimacy (35).

–Back to The Political:

- There can be other solutions to the problem of legitimacy. “Today, with the status of knowledge unbalanced and its speculative unity broken, the first version of legitimacy is gaining new vigor” (35)—that is, there is today a re-rise of the political humanist method of legitimation … its ‘subject’ grounding and ensuring legitimacy is not ‘the life of spirit’ but in “a practical subject—humanity” (35).

- Its language game is the prescriptive. Knowledge (e.g., ‘the earth spins around the sun’) is not pertaining to a truth claim, but must be in service of legitimating prescriptive (e.g., justice) (36)—knowledge is only for use in the socio-political as tool for enacting prescriptives:

- “Knowledge is no longer the subject, but in the service of the subject: its only legitimacy (though it is formidable) is the fact that it allows morality to become reality” (36).

- The relation between knowledge and society is only as means to the end. Thus, it assumes (unlike the Philosophical method) that there is no unification possible of language games; there is no metanarrative that unites it all: Prescriptives are independent of scientific knowledge; knowledge is only a means for the prescriptives.

Two closing remarks (two models of the parallel of people/knowledge roles):

- (1) Marxism: wavers between the political and practical models

- (2) Heidegger’s Rector Lecture: philosophical method blended into ontology and tainted with racism

§10: Delegitimation:

§11: Research & its Legitimation through Performativity:

Review of §§8-10 as Preface For §11:

... Now ... we have:

§11: Shows what happens to Research aspect of Science’s Game (cf. §7 for Research & Teaching as Science’s two dimensions):

(1) the methods of Science multiply (pp.42-43):

(2) the complexity of establishing proof increases (pp.44-47):

(1) Explores ‘how do we legitimate the rules of valid argument in Science?’

Traditionally, axiomatics (formal systems based on logic) legitimated such by requiring they were:

Conclusion: Science in the Postmodern Condition of Delegitimation has a vastly multiplied field of valid rules for argumentation, and legitimating progress within a game requires the consensus of experts in other games.

(2) Explores what develops from Science’s need of Proof for Proofs in the Postmodern?

Scientific proof must be ostensive--i.e., denotative language games require an addressor to name and prove that naming by showing its proof.

The best way to ‘show’ (as proving) a proof (a claim or name) is by extensive information (established body of knowledge showing what the addressor is showing).

Technology can best do this showing what is shown. Technology (technai, the power to make or do), traditionally an art, becomes mechanical, instrumental; it belongs to the language game of efficiency; creates/fuels a vicious circle: need proof-need money to make proof-need more proof-need more money/no money-no proof.

Capitalism originally has a workable solution: fund:

Power works by force: this seems to be in the game of efficiency (so should only effect science), but science is part of the social, linked to the state, hence it actually effects the truth criterion of the social.

Thus, since the proof is ostensive, to control reality is to win the game—this makes Science self-legitimating (controls the rules and reality: the competition, playing of the game, its stakes, its winners).

Conclusion: Science’s type of proof needed gives rise to technology which enacts a vicious cycle which makes the Science-State then only fund (1) applied research for short-term gain, which only aids Progress Type (A) new moves within their traditional games.

Review of §§8-10 as Preface For §11:

- §8: Showed, due the Problem of Legitimation, the merging of the Scientific & Narrative (previously described separately and the former at odds with the latter) because Science has to appeal outside of its own game to Narrative to prove its proof.

- §9: Showed how Science developed its own type of Narratives for proving its proof:

- 1) Political Route: focused on primary education, humanistic goal of liberation for ‘the people’

- 2) Philosophical Route: focused on higher ed, appended goal (a metanarrative) of being good for the ‘Life of the Spirit’ to the ideal of ‘knowledge for knowledge’s own sake’

- These routes wax and wane; (1) resurges as dominant, raises skepticism of metanarratives, makes knowledge a mere instrument to its end of liberation (makes end ‘the people’ into ‘power of State’).

- §10: Showed the Delegitimation (due rise of route (1)) in Postmodern Condition: a skepticism of grand narratives, be they used by routes 1 or 2. Reminds us the seeds of destruction inherent in Science’s language game itself (‘question all’ led to Science itself being questioned to the point it loses authority, becomes one game amongst all other valid games). Explains how this can lead to pessimism (the ‘Modern’ tendency to nostalgia or an excessive embrace of all that is new (cf. Appendix) … but asserts that Delegitimation doesn’t mean all is now barbarity.

... Now ... we have:

§11: Shows what happens to Research aspect of Science’s Game (cf. §7 for Research & Teaching as Science’s two dimensions):

(1) the methods of Science multiply (pp.42-43):

(2) the complexity of establishing proof increases (pp.44-47):

(1) Explores ‘how do we legitimate the rules of valid argument in Science?’

Traditionally, axiomatics (formal systems based on logic) legitimated such by requiring they were:

- (a) consistent;

- (c) decide-able;

- (b) complete;

- (d) independent from one another.

- (A) new moves within their traditional games, and

- (B) the invention of new games

Conclusion: Science in the Postmodern Condition of Delegitimation has a vastly multiplied field of valid rules for argumentation, and legitimating progress within a game requires the consensus of experts in other games.

(2) Explores what develops from Science’s need of Proof for Proofs in the Postmodern?

Scientific proof must be ostensive--i.e., denotative language games require an addressor to name and prove that naming by showing its proof.

The best way to ‘show’ (as proving) a proof (a claim or name) is by extensive information (established body of knowledge showing what the addressor is showing).

Technology can best do this showing what is shown. Technology (technai, the power to make or do), traditionally an art, becomes mechanical, instrumental; it belongs to the language game of efficiency; creates/fuels a vicious circle: need proof-need money to make proof-need more proof-need more money/no money-no proof.

Capitalism originally has a workable solution: fund:

- (1) applied research for short-term gain, and

- (2) basic research for long-term gain.

Power works by force: this seems to be in the game of efficiency (so should only effect science), but science is part of the social, linked to the state, hence it actually effects the truth criterion of the social.

Thus, since the proof is ostensive, to control reality is to win the game—this makes Science self-legitimating (controls the rules and reality: the competition, playing of the game, its stakes, its winners).

Conclusion: Science’s type of proof needed gives rise to technology which enacts a vicious cycle which makes the Science-State then only fund (1) applied research for short-term gain, which only aids Progress Type (A) new moves within their traditional games.

§12: Education & its Legitimation through Performativity:

This section shows what happens in the Teaching aspect of Science in the Postmodern Condition.

Education is a subsystem of the social system, which has become the creation of the Science-State model ruled by the Performativity Criterion of efficiency.

Thus, Education must create skills of two types:

Thus, Education divides between:

The student body changes; continuing education needs increase.

The transmitted content of education: information (established body of knowledge); this content can be transmitted most efficiently via computers.

This changes the nature and value of education: instead of the goal being truth, it becomes useful = sale-able = efficient.

Education today--as based on the transmission of information--may still be at the 'Imperfect Info' level ... but the 'Perfect Info' level will certainly be on the horizon:

Recent Responses to ‘Info’ Game of Education:

Interdisciplinary Studies: right direction, faces strong resistance;

Team Work: best for accomplishing tasks, hence aids only Progress Type (A).

Lyotard's Proposed Solution: dissociate 'simple' from 'extended' reproductions:

Will this solution work? It is unknowable. The only thing certain: our current state and inevitable future is the death knell for professors—professors (in the traditional sense, especially those for whom the above may be most angst-inducing, where there is something sacred about teaching and pedagogy matters as much as the most valuable things of life and what happens in teaching can never be recreated by computers and and and ... ) are not needed for either type--computers can better transmit information as instructions, and the stimulation of imaginations can certainly happen within classrooms, but also beyond them (and given many other factors, societal, economic, bureaucratic, etc., the happening of such beyond the classroom may be the way we must be and are inevitably going).

This section shows what happens in the Teaching aspect of Science in the Postmodern Condition.

Education is a subsystem of the social system, which has become the creation of the Science-State model ruled by the Performativity Criterion of efficiency.

Thus, Education must create skills of two types:

- (1) those for world competition,

- (2) those for maintaining internal cohesion.

Thus, Education divides between:

- (1) Professional Training, and

- (2) Technological Training.

The student body changes; continuing education needs increase.

The transmitted content of education: information (established body of knowledge); this content can be transmitted most efficiently via computers.

This changes the nature and value of education: instead of the goal being truth, it becomes useful = sale-able = efficient.

Education today--as based on the transmission of information--may still be at the 'Imperfect Info' level ... but the 'Perfect Info' level will certainly be on the horizon:

- In the level of ‘Imperfect Info,’ teaching still exists, but only to training for new skills in gathering info for professional and technological practices, which only grants Progress Type (A) new moves.

- In the level of ‘Perfect Info,’ the only winning move is Progress Type (B) new games; this needs imagination.

Recent Responses to ‘Info’ Game of Education:

Interdisciplinary Studies: right direction, faces strong resistance;

Team Work: best for accomplishing tasks, hence aids only Progress Type (A).

Lyotard's Proposed Solution: dissociate 'simple' from 'extended' reproductions:

- Simple Reproduction: professional & technological skills; teach to the masses

- Extended Reproduction: stimulate imagination; teach on small scale ruled by aristocratic egalitarianism

Will this solution work? It is unknowable. The only thing certain: our current state and inevitable future is the death knell for professors—professors (in the traditional sense, especially those for whom the above may be most angst-inducing, where there is something sacred about teaching and pedagogy matters as much as the most valuable things of life and what happens in teaching can never be recreated by computers and and and ... ) are not needed for either type--computers can better transmit information as instructions, and the stimulation of imaginations can certainly happen within classrooms, but also beyond them (and given many other factors, societal, economic, bureaucratic, etc., the happening of such beyond the classroom may be the way we must be and are inevitably going).

§13: Postmodern Science as the Search for Instabilities:

The pragmatics of Science emphasizes invention of new moves & new rules for language games. Today, it is seeking “crisis resolution”—to resolve the crisis of determinism, determinism being the performativity model’s premise for legitimation (i.e., efficiency seeking in order to gain power performance based model deems legitimate those moves that are determinable, fixed, certain to produce results/power, hence a System that follows a regular path).

Lyotard’s aim in §13: “to demonstrate … that the pragmatics of postmodern scientific knowledge per se has little affinity with the request for performativity” (54)—thus, to show that “Science does not expand by means of the positivism of efficiency,” that, in fact, “The opposite is true: working on a proof means searching for and ‘inventing’ counterexamples, in other words, the unintelligible; supporting an argument means looking for a ‘paradox’ and legitimating it with new rules in the games of reasoning” (54).

“Science develops …” (54). The discourse on the rules that validate Science are immanent to Science (this is postmodern science’s “striking feature” (54)), and thus inventing new rules is complex, it raises paradoxes and takes these challenges very seriously (55).

Thus … must examine the notion of The System—first, the fiction of the system, then its true nature:

The fiction of the System: systems are stable; they are based on principles of relation that are calculable; know all the variables, and one can correctly predict the evolution of a system’s performance because systems follow regular patterns, thus their evolutions follow regular paths and their activity yields normal, continuous functions.

- The mistakes this makes: Complete measurement of any given state of a system is impossible (55). Complete control over a system is impossible (55-56). Complete definition of a system is impossible (56). As you gain more accuracy, you actually get more uncertainty (56).

- “Knowledge about [e.g.] the density of air thus resolves into a multiplicity of absolutely incompatible statements; they can only be made compatible if they are relativized in relation to a scale chosen by the speaker” (57).

“Systems,” in fact, are Unpredictable: “All that can be calculated is the probability that the statement will say one thing rather than another. … ‘better’ information … cannot be obtained” (57).

Thus: “The problem is not to learn what the opponent (‘nature’) is, but to identify the game it plays” (57). E.g.:

- Dice: “is precisely a game for which this kind of ‘sufficient’ statistical regularities can be established …” (57).

- Natural Sciences: presumably nature, its referent, is indifferent (not cunning), hence more or less predictable, and so scientists make denotative utterances constituting moves and play the game against one another.

- Bridge: “the level of ‘primary chance’ encountered by science could no longer be imputed to the indifference of the die toward what face is up, but would have to be attributed to cunning ,,, to a choice, itself left up to chance, between a number of possible, pure strategies” (57).

- Human Sciences: the referent, the human, is also the player of the game (addressor and addressee), hence the game is agonistic (combative), and players develop mixed strategies—thus, here, the referent is never indifferent, but behavioral, strategic, more like bridge than dice.

Thus, we should listen to the genuine scientists who are developing ‘languages’ for their games that take into account discontinuities. One example, from René Thom, forms Catastrophe Theory (58-59): “The system is said to be unstable: the control variables are continuous, but the state variables are discontinuous” (59)—and “This provides us with an answer in the debate between stable and unstable systems, determinism and nondeterminism. … ‘The more or less determined character of a process is determined by the local state of the process’” (59). The essence of such theories is that causative processes can be reduced to an intuitively determinable form of conflict, of flux. These help us to understand how research on singularities and incommensurables are applicable to pragmatics of everyday situations (59-60).

“Postmodern science—by concerning itself with such things as undecidables, the limits of precise controls, conflicts characterized by incomplete information, ‘fracta,’ catastrophes, and pragmatic paradoxes—is theorizing its own evolution as discontinuous, catastrophic, nonrectifiable, and paradoxical. It is changing the meaning of the word knowledge, while expressing how such a change can take place. It is producing not the known, but the unknown. And it suggests a model of legitimation that has nothing to do with a maximized performance, but has as its basis difference understood as paralogy” (60).

§14: Legitimation by Paralogy:

Today:

- (1) we are skeptical of “grand narratives”; but “little narratives” remain the quintessential form of “imaginative invention,” especially in science (60).

- (2) The principle of consensus as a criterion of validation is inadequate, because:

- (a) consensus as dialogue between knowledgeable minds and free wills hearkens the emancipation grand narrative;

- (b) consensus as part of a system that uses it to regulate the system to produce efficiency and therefore power.

Thus: “The problem is therefore to determine whether it is possible to have a form of legitimation based solely on paralogy” (61).

Paralogy: {Greek: παραλογισμός paralogismós, Latin: paralogismus; para-, alongside, beside, beyond, against, contrary to + -logy, speaking, discourse, logic, knowledge, the word: a form of reasoning that does not conform to the rules of logic; an ongoing creation of meaning; a creative reasoning that engages conflicting paradigms that cause reason to break with habits, explore new games, engage creative transformations of existing games; eschews old moves relying on old principles, engages flux with humility; if logic can be considered either/or, paralogy is more like both/and}

...more, coming soon ...

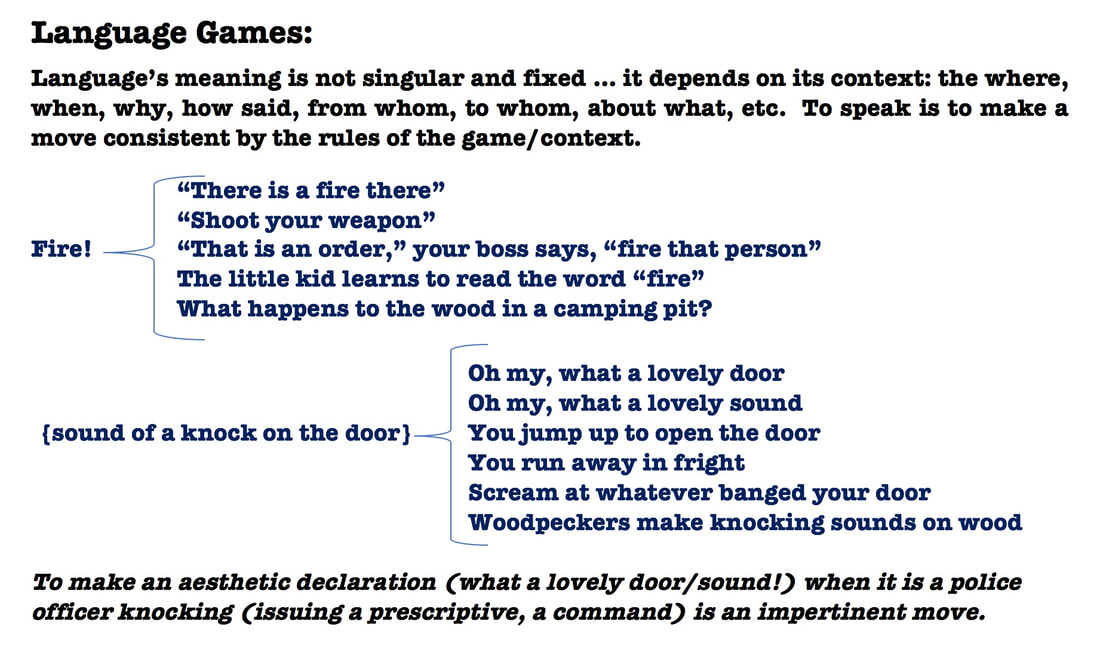

... Interlude ... More on 'Language Games' ...

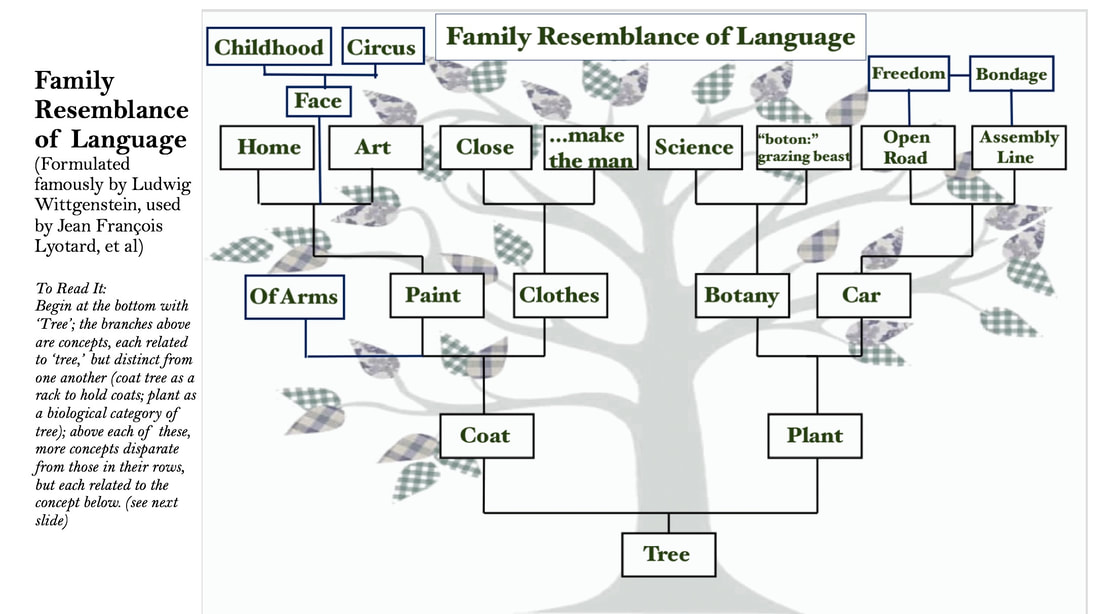

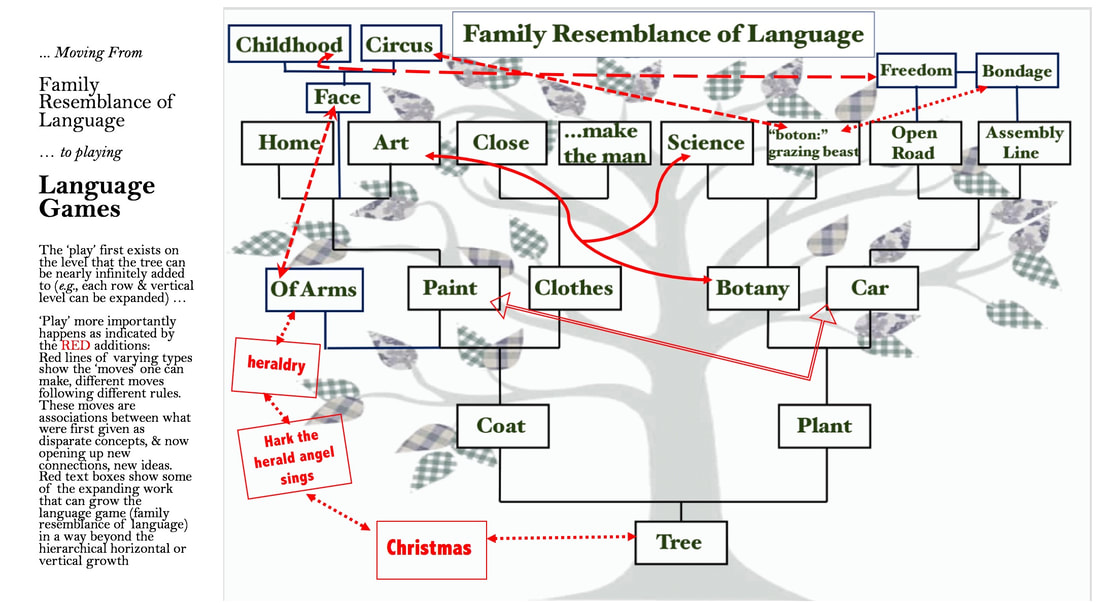

In this type of a schema, the family resemblances play out by ascent and descent along the vertical lines between concepts, thus one can most easily see where parallel family resemblances (concepts along horizontal rows) may share a (vertical) root, but play by entirely different rules.

Two Lines of Family Resemblances Elucidated:

NEXT, there is a further, more expansive game to be played that explores how commensurate or incommensurate the different moves may be:

Two Lines of Family Resemblances Elucidated:

- "Coat" can conceptually lead to "Coat of Paint;" a type of "Paint" can be "Face Paint;" one can get one's "Face Paint"-ed at a "Circus" ...

- "Plant" is the study of "Botany;" "Botany" is a "Science;" and the etymological root of "Botany" is "Boton: grazing beast" ...

- A "Coat of Arms," "Coat of Paint," & "Coat" as type of "Clothes" share a conceptual root of "Coat," but otherwise do not bear any other family resemblance.

- A "Car Plant" and "Plant" as the subject matter of "Botany" share the root "Plant," but do not otherwise bear a family resemblance.

NEXT, there is a further, more expansive game to be played that explores how commensurate or incommensurate the different moves may be:

Here, the playing out of new linkages between the concepts starts to reveal how much more of the tree may truly represent family resemblances of language ... there may be less incommensurability between the branches than it first appears by sticking to the rigid vertical or horizontal moves ... however, this play may also most easily disguise differends (incommensurate branches), covering over their different rule-books.

IV) On "What is Postmodernism?", appendix to The Postmodern Condition (1979)

- Jean-François Lyotard, “What is Postmodernism?”, 71-82, in The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, trans. Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002).

- Excerpted in Art and its Significance: An Anthology of Aesthetic Theory, third edition, ed. Stephen David Ross (New York: State University of New York Press, 1994), 559-564--this is the latter half of his full essay.

Elaboration and TEXTUAL ANALYSIS of “What is Postmodernism?”—as in the extract in Ross, A&S, pp.561-64:

He begins: modern art is that which devotes its technique to “present the fact that the unpresentable exists. To make visible that there is something which can be conceived and which can neither be seen nor made visible. …” (564).

The theoretical guide to understanding this is Kant’s sublime, in how its attention to the lack of form can serve as an “index to the unpresentable,” in how the imagination’s work therein is in abstraction (overwhelmed) when it seeks beyond, its activity like “a presentation of the infinite, its ‘negative presentation’” (564). (e.g., Kant’s citation of Exodus’ “Thou shalt not make graven images”—radical prohibition of representations.)

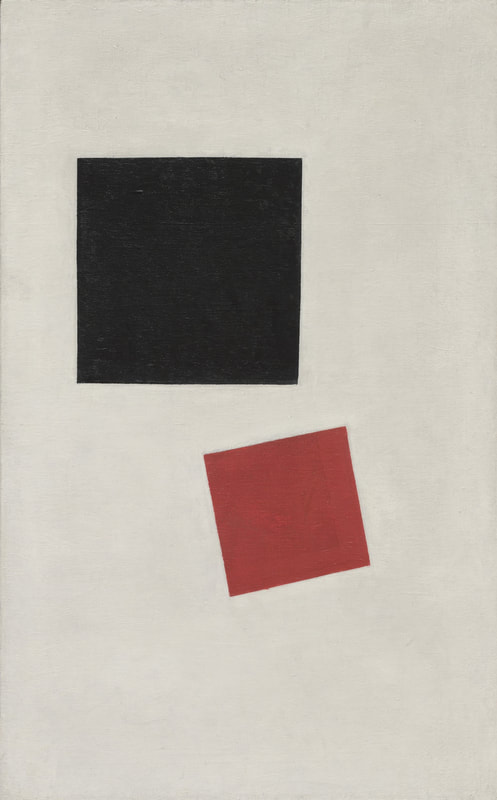

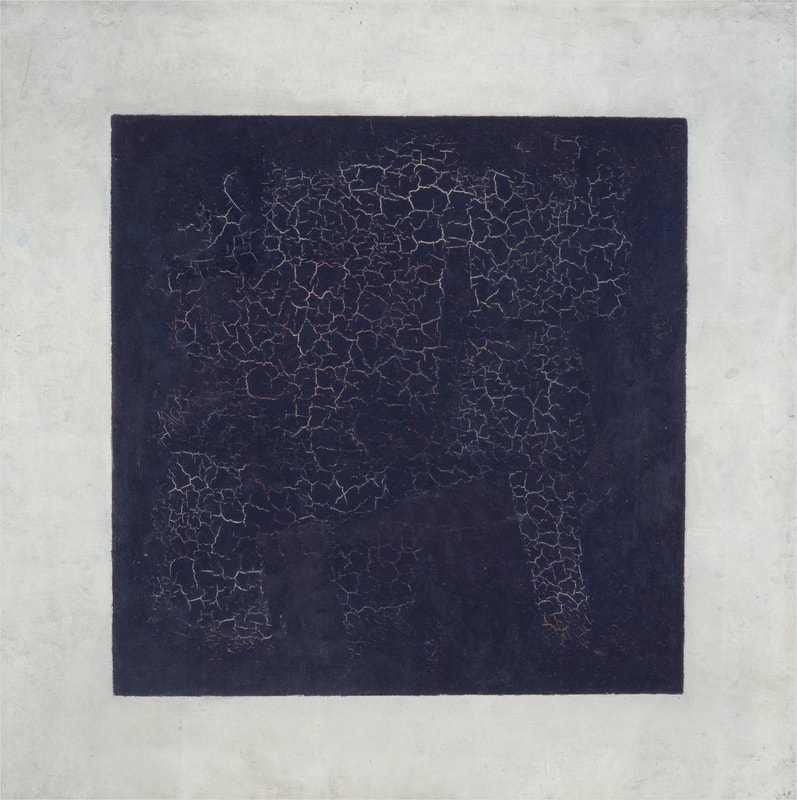

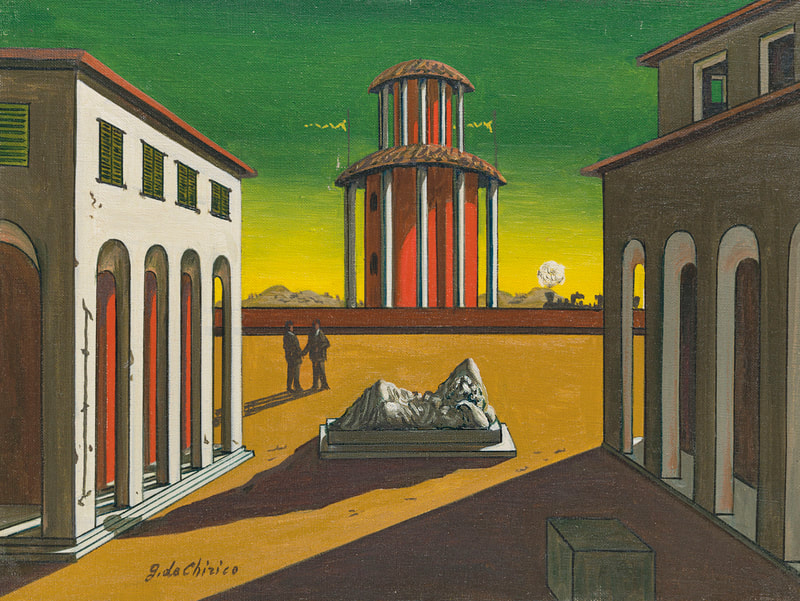

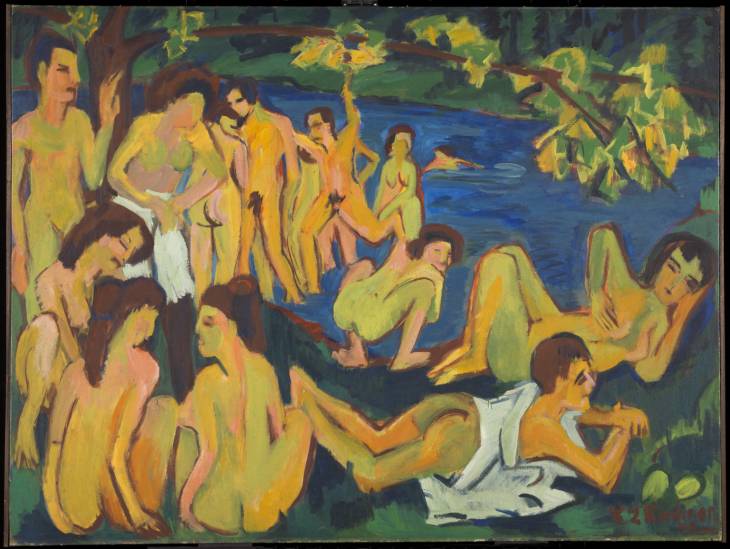

All the above characterizes sublime paintings. Such will present (as they are paintings), but negatively--e.g., Malevich’s squares: enable seeing by making seeing impossible; causing pleasure by causing pain; making allusions to unpresentable by means of presentations; reveal-conceal (564).

In Textual Analysis ... :

“… the avant-gardes are perpetually flushing out artifices of presentation which make it possible to subordinate thought to the gaze and to turn it away from the unpresentable. If Habermas, like Marcuse, understands this task of derealization as an aspect of the (repressive) ‘desublimation’ which characterizes the avant-garde, it is because he confuses the Kantian sublime with Freudian sublimation, and because aesthetics has remained for him that of the beautiful” (565).

“… the avant-gardes are perpetually flushing out artifices of presentation which make it possible to subordinate thought to the gaze and to turn it away from the unpresentable. If Habermas, like Marcuse, understands this task of derealization as an aspect of the (repressive) ‘desublimation’ which characterizes the avant-garde, it is because he confuses the Kantian sublime with Freudian sublimation, and because aesthetics has remained for him that of the beautiful” (565).

- The subordination of thought to gaze is a way of describing the Kantian aesthetic judgment--i.e., a judgment of taste, hence neither one concerned with reason or understanding, and reinforced as being disinterested, not concerned with the actual object in existence. The judgment of the sublime, especially, enacts such a subordination in that it is a most powerful and profound overwhelming of the intellectual capacities.

- The turning away from the unpresentable is acknowledging that the sublime (as described on p.564) engages the lack of form as an index, the negative presentation, the allusions to the unshown by what is shown, the cyclical work of revealing-concealing—think about how Kant argues that the mind “conquers” the formlessness and inability by revelation of the ability of mind to think its own inability.

- Habermas and Marcuse—the excerpt we are reading is the latter half of Lyotard’s full essay; in his full essay, he begins with acknowledging contemporary critics of postmodernism, most especially and explicitly Jürgen Habermas, who considers postmodernism as having caused a harmful “splintering of culture and … separation from life” leaving the individual only experiences of “‘desublimated meaning’ and ‘destructed form’” leading to nothing but “immense ennui” and believes that the mission of art is bridge all the divides between “cognitive, ethical, and political discourses, thus opening the way to a unity of experience” (Lyotard, “What is Postmodernism?”, 71-82, in The Postmodern Condition, 72). Lyotard rejects this thoroughly. For him, such synthesis or unification is a blurring over of true and genuine and profoundly impactful incommensurabilities between these differing discourse regimes. In the quote above, he is saying Habermas is confusing the work of the sublimes revealing-concealing work as a desublimation in the Freudian sense of the repressive work the ego does to drives from the more libidinous and unconscious realms of mind in order to make socially-appropriate activity. Marcuse (whom we’ll read a little at the end of the semester) is also guilty of a blurring of the Kantian into the Freudian frames in his promotion of art as liberatory. For Lyotard’s charge of Habermas as remaining within the art of the beautiful, recall how, for Kant, the judgment of the beautiful yields a flush sense of the furtherance of life since imagination’s free play is generative of rich possibilities that, out of the aesthetic judgment, Understanding can certainly take up and work through as conceptual possibilities concerning knowledge. That sort of work of art generating something that Understanding or Reason can then use in terms of knowledge or morality is what Habermas especially wants. The ways of contemporary society and its art he is analyzing, however, is what accords with judgments of the sublime, not of the beautiful.

§ “The Postmodern” (p.562ff):

“What, then, is the postmodern? … It is undoubtedly a part of the modern” (562)--i.e., ‘postmodern’ does not name something diachronical (i.e., as if a time period after the modern period).

Instead: “A work can become modern only if it is first postmodern” (562)--i.e., in addition to the postmodern not being a chronologically subsequent period, Lyotard is showing their cyclical relation, interdependence, his examples just before this show the chain of art innovators being only innovative by having something prior to challenge and undo, but that undoing is more a reconstituting of the prior into something additionally developed.

Thus: “Postmodernism thus understood is not modernism at its end but in the nascent state, and this state is constant” (562)--i.e., the challenger is present in the inceptive work; the dynamic state of creation is postmodernism’s proliferate ruptures, and is on going … perhaps think of a roiling ocean from which moments of stable innovation can be seen coming out, even as they are part of the roil, and then these moments will be further challenged by new innovations or works, also of, from, and back to the roil.

Nevertheless: Lyotard does further and better elaborate two modes within sublime art (562)—which he identifies as modern and postmodern sublime aesthetics on p.563—but first just note the three accounts of where to place emphasis:

- (1) on the powerlessness of the faculty of presentation—the nostalgia for presence, the obscure, futile will;

- (2) on the power of the faculty to conceive—the inhumanity;

- (3) on the increase of being and jubilation resulting from invention of new rules of the game.

Now, note the differentiation under two labels: melancholia (melancholy) and novatio (making new, as novel or renew):

- Melancholia: German Expressionists; Malevitch; Chirico; (regret)

- Novatio: Braque and Picasso; Lissitky; Duchamp; (assay)

While the differences are minute and may exist at once in the same piece, “they testify to a difference (un differend) on which the fate of thought depends and will depend for a long time, between regret and assay” (563).

Note the further elaboration in and between Proust (akin melancholia) and Joyce (akin novatio):

- In Both: allusions to something that refuses to be made present;

- In Proust: the allusion causes an elusion of the identity of consciousness (i.e., the price of the allusion is the coherent subject as victim to the excess of time)

- In Joyce: the allusion causes an elusion of the identity of writing (i.e., the price of the allusion is the coherency of writing as victim to the excess of the book/literature)

This first difference within enactments of the first similarity further mean:

- In Proust: the allusions (calling forth the unpresentable) are done in unaltered language (i.e., syntax and vocabulary, his writing, is still in the form inherited, belongs to the genre of novelistic narration); so, while it somewhat subverts the traditional form, the unity of the book is not seriously challenged;

- In Joyce: the allusions (calling forth the unpresented) are done in the signifier (i.e., all features of writing, (narrative, syntax, style) are put into play without regard to the unity of the book).

Now, Lyotard more clearly states the differences between the modern and postmodern:

- Modern:

- Aesthetic of the sublime, but a nostalgic one (not “real”);

- Unpresentable put forward as missing contents;

- Form (b/c of recognizable consistency) offers audience something for solace and pleasure;

- (additional e.g., the fragment, especially The Athaeneum)

- Postmodern:

- Is “… that which, in the modern, puts forward the unpresentable in presentation itself;”

- Denies itself solace of good form;

- Denies consensus of taste by which to share nostalgia for the unattainable;

- Searches for new presentations—not for enjoyment, but to impart stronger sense of unpresentable;

- Work produced ungoverned by preestablished rules;

- Work produced cannot be determinately judged (by familiar categories);

- Work searches for new/apt rules and categories (i.e.: “working without rules in order to formulate the rules of what will have been done” (564);

- Work has the characteristics of the event

- (“event” (French: Arrive-t-il?; German: Ereignis) is critical to postmodernism as it was to Heidegger’s phenomenological ontology; it indicates a happening, something with both noun and verb senses as activity and site, relating intimately to that from and by which meaning can be situated, thus relating intimately to Being and to language--e.g., in Heidegger, it connects with death (presence and deferral by which we define our Being) and the call of conscience (unspoken, from us, calls us back to reflect upon ourselves; there and otherwise, non-specific indications that solicit our response; is a coming to presence and that which presences);

- (additional e.g.: the essay, especially Montaigne’s)

Postmodernism’s charge: “not to supply reality but to invent allusions to the conceivable which cannot be presented” (564).

This task is not to thought to (to be capable or likely to) “effect the last reconciliation between language games (which, under the name of faculties, Kant knew to be separated by a chasm), and that only the transcendental illusion (that of Hegel) can hope to totalize them into a real unity” (564):

- i.e., postmodernism’s work will not unify experience (refer back to the explanation of the opening vs. Habermas); only a transcendental illusion can (and this is not a good thing, it will blur over incommensurates, again, refer back to the opening);

- specifically: “reconciliation between language games”—Lyotard’s abiding concern is for the activity and consequences of language games. Language games, adopted from Ludwig Wittgenstein, are ways of linguistic and epistemological linking, for example, linking different linguistic-conceptual ‘families’ like how ‘coat’ can refer to paint or an article of clothing, or different phrase regimes together like how cognitive assertions of sexual difference blur into moral determinations of work appropriate for men versus women. The motivating consequence of such linkages in Lyotard’s work The Differend is the violence done to holocaust survivors when their testimony is barred by historical revisionists who demand ‘proof’ in a strictly ostensive form (i.e., a victim who can testify to the experience of a gas chamber is rendered paradoxical because only those who were dead would be proof in their logical frame)—this is an example of what he calls ‘a differend,’ the incommensurate gulf between two or more language games between which there is no just criterion for judgment. Here, it is all the many possibilities of differends that would be blurred over if such a reconciliation or unification of all was possible;

- “(which under the name of faculties, Kant knew to be separated by a chasm)”—here, Lyotard is showing that what he is talking about re: language games is synonymous to Kant on the differences between Understanding and Reason, that ‘chasm’ between them being the nebulous realm where the power of judgment resides and works; aesthetic judgment can work with either, contribute its yield to either, and aid the two faculties working together, but is unique from either and therefore also capable of what is incommensurate with either.

- “transcendental illusion (that of Hegel) can hope to totalize them into a real unity”—here, Lyotard is referring to the synthetic capacities and power of Hegel’s dialectic as only that that can blur over the incommensurable divides (between language games or faculties) and rend totalizing systems—this is no hopeful answer or goal!, for Lyotard, this is the work of terror. His view of the dialectic is as a sort of over-system that coheres all disparate parts (theses and antitheses) into a whole (syntheses) by a strangling logic; it ‘works,’ but does violence to difference, and, mostly, is at odds with what is (difference and dynamism is inherent and infinite).

Thus, since the postmodern charge is to invent allusions and to avoid totalization, he concludes: “Let us wage a war on totality; let us be witnesses to the unpresentable; let us activate the differences and save the honor of the name” (564).

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by MacHighway