Jean-François Lyotard's The Differend . . . << chapters two & three >>

|

C O N T E N T S : (1) Chapter Two: "The Referent, The Name" (2) Chapter Three: "Presentation" |

Lyotard’s The Differend, ch. 2: “The Referent, The Name”

Outline:

Chapter One showed us what was at risk: the ontological status of the witness, due to the revisionist’s “logic” requiring crude ontological evidence (‘prove/show it exists’). So … chapter two: let us explore what is indicated by the ontological: referent and name.

§§47-54:

- Slippage in Phrases (e.g., deitics, referents, names—slippage and ‘conversions’ * )

- How verify despite ‘slippage’? *

- Need linkages with other phrase types (explored via analytics & ancients)

- (i.e: link showing, naming, & describing phrases from, respectively, ostensive, nominative, & cognitive genres of discourse)

- Need linkages with other phrase types (explored via analytics & ancients)

- How verify despite ‘slippage’? *

- Reality must be fixed

- How? Need linkages over the ‘hollow’ *

- Ostensive fails (explored via phenomenology (Descartes, Kant, Husserl))

- How? Need linkages over the ‘hollow’ *

- Ostensive fails because Sense is ‘limitless’ *

- Historians fail (explored via translation, transcription)

- Logical Genre ≠ Cognitive Genre revealed by failure due to sense of ‘possible’ *

- But … what if reality is a matter of the future?

- Future fails because of ‘negation’ * (expled. via essential., phen., ordinary lang.)

- But … what if reality is a matter of the future?

- Why we cannot fail: Auschwitz

- So … “complex feeling” … what will be explored in chap. 3: “Presentation”

- * Note: ‘Slippage’ = ‘Conversion’ = ‘Hollow’ = ‘Gap’ = ‘Limitless’ = ‘Shadow’ = ‘Possible’ = ‘Negation’ (cf. §§53, 59, 83, 90, 75, 83, 84, 90, 91)

- … i.e., what he first revealed about the ontological (it always indicates slippage) is what causes the continual failures in every move he makes to try to solve the problem of how to verify the ontological (in order to establish reality) by linking showing, naming, and describing phrases (i.e., phrases in the ostensive, nominative, and cognitive genres of discourse).

Textual Analysis:

§47

To hold that reality is founded by the phrase, that the phrase situates us in its universe, and that “effectuation of verification procedures,” i.e., successful verification creates reality is counter to the spontaneous idea of reality we hold

(note, this can be understood as an implicit reference to Descartes’ Third Meditation, wherein he rejects that the source of ideas is adventitious because even while spontaneity suggests so, this premise cannot be held up under the sustained light of reason).

In other words, our everyday way of thinking reality is realism: the belief that things have an independent existence from the “I.”

§48

To refute the common idea of reality is parallel to the dilemma in §8 [“Either you are a victim of a wrong, or you are not. If you are not, you are deceived (or lying) in testifying that you are. If you are, since you can bear witness to this wrong, it is not a wrong, and you are deceived (or lying) in testifying that you the victim of a wrong” (§8)].

§49

“‘I was there, I can talk about it.’ This same principle governs Faurisson’s argument: ‘to have really seen, with his own eyes’ (No. 2).”

Recall the how the lack of this evidence made the survivor’s testimony weak in the Nuremberg Trials.

Lyotard cites Hartog, who names the authority of this eyewitness testimony “Autopsy:” an exhaustive examination, often used to find the cause of death; etymologically, from the Greek Autoptes, eyewitness from the conjunction of Auto, self, and Optos, seen.

§47

To hold that reality is founded by the phrase, that the phrase situates us in its universe, and that “effectuation of verification procedures,” i.e., successful verification creates reality is counter to the spontaneous idea of reality we hold

(note, this can be understood as an implicit reference to Descartes’ Third Meditation, wherein he rejects that the source of ideas is adventitious because even while spontaneity suggests so, this premise cannot be held up under the sustained light of reason).

In other words, our everyday way of thinking reality is realism: the belief that things have an independent existence from the “I.”

- Realism: Things exist independent of I. Objective, independent reality (those trees in the forest, they fall and make noises even if no one sees or hears them; e.g. materialism).

- Idealism: Things do not exist independent of the mind. Subjective, dependent reality (those trees in the forest, they only fall and make noises in so far as someone is there and experiences them as tress, falling).

§48

To refute the common idea of reality is parallel to the dilemma in §8 [“Either you are a victim of a wrong, or you are not. If you are not, you are deceived (or lying) in testifying that you are. If you are, since you can bear witness to this wrong, it is not a wrong, and you are deceived (or lying) in testifying that you the victim of a wrong” (§8)].

§49

“‘I was there, I can talk about it.’ This same principle governs Faurisson’s argument: ‘to have really seen, with his own eyes’ (No. 2).”

Recall the how the lack of this evidence made the survivor’s testimony weak in the Nuremberg Trials.

Lyotard cites Hartog, who names the authority of this eyewitness testimony “Autopsy:” an exhaustive examination, often used to find the cause of death; etymologically, from the Greek Autoptes, eyewitness from the conjunction of Auto, self, and Optos, seen.

An aside question: Is there not something a little mad in the idea of self-witnessing? Witnessing suggests a relation between the seer and seen ... specifically, a relation of intentionality wherein there is the seer who intends (sees) something (other). Self-witnessing makes the intentional directedness from the subject bend back around to observe the subject. The seer and seen are one. Or, does self-witnessing (what one can also call self-consciousness) initiate the duplicity of the self, make the self both self and not-self? Hegel posits the development of self-consciousness as the result of consciousness encountering another that is not itself, and this is the very marker of humanity being more than mere conscious thing. This development is the most normal presumption, say in childhood education, when the baby ‘learns’ the differentiation of itself from what is not it. And this is also the very activity that makes the command inscribed above the entry to the Oracle of Delphi ~~the Socratic command to “know thyself”~~ even possible. Otherwise said in the language of other postmoderns (e.g., Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari), it is also the “becoming schizophrenic” that is necessary in becoming human. An intriguing depiction of such self-witnessing as perhaps a little mad can be read in Jean-Paul Sartre’s novella Nausea.

- (Image: The Evil Eye, Blenheim Palace ... cf. ~here~)

“To Faurisson, it can be answered that no one can see one’s own death” (§49):

This is his same answer to realism, that no one can “see” reality, as we conceive it. “That would be to suppose that reality has a proper name, and a proper name is not seen …” Lyotard references Saul Kripke (1980: 44) on this point. ... Question: What do you take this to mean?

Onomatology (Onomastics): the study of proper names. It is the genus which includes toponymy and anthroponymy (see below).

“Naming is not showing.”

A phrase that names is different than a phrase that shows; proper names and ostension or description function under different rules.

Lyotard explains with the personification of Jean, who says to Jacques: “I assure you that Louis was there,” to which the latter can verify these names by asking, “where?” and Jean can refer to the context in their discussion, “at the concert I was telling you about!”

All other aspects, where this is, when it was, etc. can all be situated into a network of meaning, a “system of cross-references which is independent of the space-time presented by his first phrase …” (§49). This system of cross-references is a recourse to “chronological, topographical, toponymic, and anthroponymic systems …” :

… these all provide the means to verify reality but they do not establish that Jean himself was there, i.e., they do not constitute evidence in an ontological proof for the existence of Jean.

- Lyotard is quipping Heidegger’s infamous declaration that while we exist (define ourselves through this projectoral being) as Being-towards-death, death is the one event that we, ourselves, cannot experience because to grasp something requires one to stand outside or beyond it and be able to reflect back over it (given how we exist in time, in our fluid “now,” we recollect the past and anticipate the future; death, however, forbids this anticipation).

This is his same answer to realism, that no one can “see” reality, as we conceive it. “That would be to suppose that reality has a proper name, and a proper name is not seen …” Lyotard references Saul Kripke (1980: 44) on this point. ... Question: What do you take this to mean?

Onomatology (Onomastics): the study of proper names. It is the genus which includes toponymy and anthroponymy (see below).

“Naming is not showing.”

A phrase that names is different than a phrase that shows; proper names and ostension or description function under different rules.

Lyotard explains with the personification of Jean, who says to Jacques: “I assure you that Louis was there,” to which the latter can verify these names by asking, “where?” and Jean can refer to the context in their discussion, “at the concert I was telling you about!”

All other aspects, where this is, when it was, etc. can all be situated into a network of meaning, a “system of cross-references which is independent of the space-time presented by his first phrase …” (§49). This system of cross-references is a recourse to “chronological, topographical, toponymic, and anthroponymic systems …” :

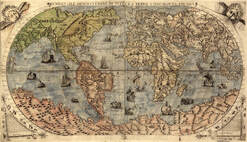

- Chronological system: last week, tomorrow, now, etc. (e.g., the Paleozoic Era; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, River of January).

- Topographical system: a description of structure, mapping surface features; (examples would include a visual or written map of hydrographic, geographic, man-made features, e.g., Three Sisters, OR, three mountains; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, River of January, therein a mountain Pao d’azcar, loaf of sugar, how sugar was made in an oval cone; Buenos Aires, good air).

- Toponymic system: topos, place, plus onuma, name: a system of place names, their origins, meanings, and use—it is a study of place names similar to how etymology studies the origins of words in language (e.g., Silver City, NV, city of silver mines; Oro Preto, Brazil, (Portuguese: gold black) gold was discovered, mined there by African slaves).

- Anthroponymic system: anthropos, human, plus onuma, name: a system of naming relating to humans; information relating to human names (important especially as a means of preserving information or uses of language that have disappeared from common usage) (e.g., Walton, people who lived in a walled town; Taylor, person was a tailor; Shumacher, person who makes shoes; Smith, a blacksmith).

… these all provide the means to verify reality but they do not establish that Jean himself was there, i.e., they do not constitute evidence in an ontological proof for the existence of Jean.

§50

Deictics: (dik-tiks) from the Greek, deiktos, demonstrative; a word or expression whose meaning is dependent upon the context in which it is used, for examples: here!, now!, next Tuesday, you!, that, this, etc.

The origin, however, of the deictics is not a static one, as “this” or “here” are most fluid, but they show origins that are presented or co-presented with the universe of the phrase in which they appear. Deictics appear and disappear with the phrase (Lyotard references Hegel and Gardies).

§51

The fluidity of deictics and how they require context (for sense):

To understand a deictic, one must think in terms of its current origin.

§52

The fluidity of deictics and how they require context (for other instances, too):

“The name he bears is a received one (though not necessarily from ‘me’), and it may be that every proper name must be a received one” (§52).

§53

The above is the “… conversion of a proper name from the position of ‘subject of the uttering’ to that of ‘subject of the utterance’…” (§53).

§54

“The displacement undergone by the ‘subject of the uttering’ when, through naming, it becomes the subject of the utterance, presents no particular obscurity” (§54).

“There is no question of validating the truth of a name: a name is not a property attributed to a referent by means of a description (a cognitive phrase). It is merely an index by which, in the case of the anthroponym, for example, designates one and only one human being” (§54).

To verify “red,” we may consult a catalogue of colors and match the referent in question with the book. To verify “Sally,” we cannot turn to any relatively fixed catalogue. “Sally” is an index, a means of designating that girl rather than that one.

We could validate her name by asking for her passport, but we cannot by reference to her name alone. “The name adds no property to him or her” (§54).

This reveals another genre of discourse: denominative phrases. “This I call x (baptism), or That is called y (training) is not a cognitive phrase. Nor is it an ostensive one (Nos. 62, 63)” (§55).

Deictics: (dik-tiks) from the Greek, deiktos, demonstrative; a word or expression whose meaning is dependent upon the context in which it is used, for examples: here!, now!, next Tuesday, you!, that, this, etc.

- “Deictics relate the instances of the universe presented by the phrase in which they are placed back to a ‘current’ spatio-temporal origin so named ‘I-here-now.’ These deictics are designators of reality” (§50).

The origin, however, of the deictics is not a static one, as “this” or “here” are most fluid, but they show origins that are presented or co-presented with the universe of the phrase in which they appear. Deictics appear and disappear with the phrase (Lyotard references Hegel and Gardies).

§51

The fluidity of deictics and how they require context (for sense):

To understand a deictic, one must think in terms of its current origin.

- Lyotard notes that to understand him, one must think of the meaning of origins of his sample phrases rather than the sample phrases he gave a few lines ago. “The reader makes a difference between now and now (or the now)” (§51). To speak of the now (a philosophical, temporal category) is different than to be speaking of now (this instant). One must grasp the four instances in the phrase universe to correct understand them.

§52

The fluidity of deictics and how they require context (for other instances, too):

- Lyotard demonstrates how the addressor of a phrase can also become a referent of/in the same phrase. Lyotard writes: “… Kant writes of the French Revolution that it aroused the enthusiasm of its spectators” (§52); Kant is the addressor of the phrase about the French Revolution arousing the enthusiasm of its spectators but Kant is the referent (the subject of the utterance) in Lyotard’s phrase. They are distinct, but, he could not say the latter, that Kant is the referent without saying the former, that Kant said such.

“The name he bears is a received one (though not necessarily from ‘me’), and it may be that every proper name must be a received one” (§52).

- Question: What does Lyotard mean by this, why must we, perhaps, receive our proper name?

§53

The above is the “… conversion of a proper name from the position of ‘subject of the uttering’ to that of ‘subject of the utterance’…” (§53).

§54

“The displacement undergone by the ‘subject of the uttering’ when, through naming, it becomes the subject of the utterance, presents no particular obscurity” (§54).

- Gottlob Frege (1848-1925) German logician/philosopher at Jena (elder to Russell)

- Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) British logician/philosopher at Cambridge (anti-idealism; teacher to Wittgenstein)

- A debate on the relation between sense and referent.

“There is no question of validating the truth of a name: a name is not a property attributed to a referent by means of a description (a cognitive phrase). It is merely an index by which, in the case of the anthroponym, for example, designates one and only one human being” (§54).

To verify “red,” we may consult a catalogue of colors and match the referent in question with the book. To verify “Sally,” we cannot turn to any relatively fixed catalogue. “Sally” is an index, a means of designating that girl rather than that one.

We could validate her name by asking for her passport, but we cannot by reference to her name alone. “The name adds no property to him or her” (§54).

This reveals another genre of discourse: denominative phrases. “This I call x (baptism), or That is called y (training) is not a cognitive phrase. Nor is it an ostensive one (Nos. 62, 63)” (§55).

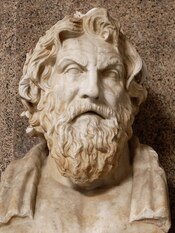

Antisthenes Notice:

Antisthenes: ca. 445-365 b.c.e; Greek philosopher, student of Gorgias first and then Socrates. The reputed founder of Cynicism (he did not use the term, but Diogenes of Sinope—the template of the cynic, an extreme ascetic, Diogenes Laertius reports that Plato described him as “A Socrates gone mad” (bk 6, ch 54), he was known for extreme anti-conventional behavior—was eager to associate himself and his movement with Antisthenes); he adopted / promoted an ethical life based on asceticism (life’s aim is virtue, not pleasure). Only fragments remain of his supposedly extensive writings (Diogenes Laertius claims them at over ten volumes), including dialogues and critiques of his contemporaries.

(image: Antisthenes, portrait bust, ca. 1774, Museo Pio-Clementino)

In logical studies, he was concerned with the problem of the One and the Many. Predication, for Antisthenes, is circular or false; definition is merely a means of stating identity.

Lyotard reports on two of his paradoxes, as reported by Aristotle when the latter is establishing his rules for dialectics:

First Paradox (pp.35-7): concerns error & contradiction: “that contradiction is impossible” (Aristotle, Topics 104b21).

Aristotle’s Metaphysics V is a “catalogue of notions” wherein falsehood is described as: “A false phrase (logos) is one that refers to non-existent objects, in so far as it is false. Hence every phrase is false when applied to something other than that of which it is true, e.g. the phrase that refers to a circle is false when applied to a triangle. In a sense there is one phrase for each referent, i.e., the phrase that refers to its ‘what its being was’ [ce qu’était qu’être] … but in a sense there are man, since the referent itself and the referent itself modified in a certain way [with some property] are somehow the same, e.g. Socrates and musical Socrates. The false phrase is not the phrase of anything, except in a qualified sense. Hence Antisthenes foolishly claimed that nothing could be described except by its own phrase … --one phrase to one referent; from which it followed that there could be no contradiction, and about that one could not be misled” (Lyotard, p. 35-6, Aristotle, Metaphysics 1024b27-34).

Why this is so odious (to Aristotle and all the later doxography, the opinions of the learned), Lyotard tells us, is because of the “amphibology of the Greek verb legein: to say something, or to talk about something, to name something?” (p.36).

There is a similar odious-ness in the revisionist’s logical bind

Amphibology: ambiguous grammatical structure in a sentence

Legein, the Greek verb “to say something,” or “to talk about something,” “to name something,” also, perhaps, “discoursing [about something].”

It is also a verb much used in Heidegger’s Being and Time to establish the linkage between humanity as the rational animal and the talking animal:

--“In the ordinary and also the philosophical ‘definition,’ Dasein, that is, the Being of man, is delineated as zoon logon echon [living animal able to speak; rational animal], that creature whose Being is essentially determined by its being able to speak. Legein [discoursing] (see section 7 B) is the guideline for arriving at the structures of Being of the beings we encounter in discourse and discussion” (Martin Heidegger, Being and Time).

Can there be falsity in Legein, in talking about some thing? Can one be misled?

Can one be misled “When one talks about the thing (pragma) to which the phrase (logos) refers, or when one does not?” “When one talks about it” “And one who talks, talks about the thing which one talks about and no other?” That thing is distinct from other things; it exists, and if one talks about things that exist they talk truthfully. So, if someone talks in this way they talk the truth, and they will not mislead. So, how can one be misled?

This argument shows the impossibility of contradiction.

The next version runs:

If neither of us say anything (neither says the logos of the thing), we will not contradict.

If I say the logos of the thing and you do not, the argument implies there will be no contradiction.

A final implication is that if I say something and you say something, we will not contradict because if you say X and I say Y, we are talking about two different things, not the same thing, therefore there is no real contradiction, we are just talking differently.

This last one works because we switch from Legein meaning to talk about something to its other legitimate meaning, to name something. If the requirement is that one thing has one name, and we seem to contradict, then really we are talking of two things, not one:

This necessitates that we believe in the hèn eph ’ hènos [one for each one] that Aristotle ascribes to Antisthenes, that is, one name designated to one thing. “And, if there is no error, it is because there is no Not-Being: the referent of a false phrase is not a nothingness, it is an object other than the one referred to” (p.36).

Lyotard notes that this way of avoiding contradiction is conducted by the two sophists slipping through the breach opened between Being and saying by Parmenides and the “neither Being nor Not-Being” of what is talked about in Gorgias (cf. Gorgias Notice).

So … “What can be said about the referent? ‘Before’ knowing whether what one says or will say about it is true or false, it is necessary to know what one is talking about [i.e. consensus, re: Plato Notice]. But how can it be known which referent one is talking about without attributing properties to it, that is, without already saying something about it? Antisthenes, like certain Megarans and like the Stoics later on, asks whether signification precedes or is preceded by designation. The thesis of nomination gets him out of the circle. The referent needs to be fixed; the name, as Kripke says, is a rigid designator that fixes the referent” (p. 36-7).

The problem: “Designation is not, nor can it be, the adequation of the logos to the being of the existent” (p.37). cannot have a one to one correspondence of word – being.

Names are not derived from or motivated by the named; to maintain this, one must know the essence of the thing before one names the thing, and how is this possible?

Antisthenes’ Nominalism: Nominalism is the belief that universals or ideas are mere names to which no reality corresponds; names mean nothing, what is real are the particular things named, esp. cf., William Ockham—Nominalism is an active designation, it creates, it is a Poiein: Greek, “to create,” it “isolates singularities in the undetermined…” (p.37).

The opposite of Antisthenes’ nominalism is the “Eponymy of the name” (cf., Gérard Gennette, Mimologiques, Paris, 1976, 11-37).

Eponymy: giving one’s name to something,

Second Paradox (p.37): (from Aristotle on Antisthenes):

Concerns determination, specifically, logos as designator: Aristotle notes that “house” can mean all the matter that makes up a house, its bricks and such, or the final form of a house that makes them matter into a shelter.

If one speaks of a house as all the material that makes it up, one has not identified the ousia, the being, of the house. But, how can the being of the house be determined if not by all of its parts?

“Therefore the difficulty which was raised by the school of Antisthenes and other such uneducated people has a certain appropriateness. They stated that the ‘what it is’ … cannot be defined (for the definition so called is a long phrase …); but of what ‘sort’ … a thing, e.g. silver, is they thought it possible to explain, not saying what it is but that it is like tin. Therefore one kind of substance (ousia) can be defined and phrased …, i.e., the composite kind, whether it be the object of sense or of reason; but the primary elements of which this consists cannot be defined, since a definatory phrase … predicates something of something, and one part of this definition must play the part of the matter and the other that of form (Metaphysics VIII 1043 b 23-32)” (p. 37).

Lyotard notes the remarkable concession given to nominalism herein. But, it is essentially wrong because “… simples are not defined, they are named” (p.37). The simple, “whatever its grammatical nature, thus has the value of a name” (p.37).

Lyotard concludes by reinscribing Antisthenes’ problem into Aristotle’s vocabulary: “… one can perhaps say the ‘what its being was’ of a referent, but this referent would first have to be named ‘before’ any predication is made about it. The simple or the elementary is not a component of the object, it is its name and it comes to be situated as referent in the universe of the definitional phase. It is a simple – hence prelogical – logic which by itself is not pertinent with regard to the rules of truth (Wittgenstein, PhU: §49)” (p. 37).

Antisthenes: ca. 445-365 b.c.e; Greek philosopher, student of Gorgias first and then Socrates. The reputed founder of Cynicism (he did not use the term, but Diogenes of Sinope—the template of the cynic, an extreme ascetic, Diogenes Laertius reports that Plato described him as “A Socrates gone mad” (bk 6, ch 54), he was known for extreme anti-conventional behavior—was eager to associate himself and his movement with Antisthenes); he adopted / promoted an ethical life based on asceticism (life’s aim is virtue, not pleasure). Only fragments remain of his supposedly extensive writings (Diogenes Laertius claims them at over ten volumes), including dialogues and critiques of his contemporaries.

(image: Antisthenes, portrait bust, ca. 1774, Museo Pio-Clementino)

In logical studies, he was concerned with the problem of the One and the Many. Predication, for Antisthenes, is circular or false; definition is merely a means of stating identity.

Lyotard reports on two of his paradoxes, as reported by Aristotle when the latter is establishing his rules for dialectics:

First Paradox (pp.35-7): concerns error & contradiction: “that contradiction is impossible” (Aristotle, Topics 104b21).

Aristotle’s Metaphysics V is a “catalogue of notions” wherein falsehood is described as: “A false phrase (logos) is one that refers to non-existent objects, in so far as it is false. Hence every phrase is false when applied to something other than that of which it is true, e.g. the phrase that refers to a circle is false when applied to a triangle. In a sense there is one phrase for each referent, i.e., the phrase that refers to its ‘what its being was’ [ce qu’était qu’être] … but in a sense there are man, since the referent itself and the referent itself modified in a certain way [with some property] are somehow the same, e.g. Socrates and musical Socrates. The false phrase is not the phrase of anything, except in a qualified sense. Hence Antisthenes foolishly claimed that nothing could be described except by its own phrase … --one phrase to one referent; from which it followed that there could be no contradiction, and about that one could not be misled” (Lyotard, p. 35-6, Aristotle, Metaphysics 1024b27-34).

Why this is so odious (to Aristotle and all the later doxography, the opinions of the learned), Lyotard tells us, is because of the “amphibology of the Greek verb legein: to say something, or to talk about something, to name something?” (p.36).

There is a similar odious-ness in the revisionist’s logical bind

Amphibology: ambiguous grammatical structure in a sentence

Legein, the Greek verb “to say something,” or “to talk about something,” “to name something,” also, perhaps, “discoursing [about something].”

It is also a verb much used in Heidegger’s Being and Time to establish the linkage between humanity as the rational animal and the talking animal:

--“In the ordinary and also the philosophical ‘definition,’ Dasein, that is, the Being of man, is delineated as zoon logon echon [living animal able to speak; rational animal], that creature whose Being is essentially determined by its being able to speak. Legein [discoursing] (see section 7 B) is the guideline for arriving at the structures of Being of the beings we encounter in discourse and discussion” (Martin Heidegger, Being and Time).

- --The definition of Dasein will relate to Being and to language, as those beings who can speak. Logos is defined as speech, word, reasoning, ground—that from which we come; Noein is defined as an intuitive apprehending, a (re)presentation; a thought.

- --Lyotard refers to this in §15: survivor cannot not speak as in the case for stones.

Can there be falsity in Legein, in talking about some thing? Can one be misled?

Can one be misled “When one talks about the thing (pragma) to which the phrase (logos) refers, or when one does not?” “When one talks about it” “And one who talks, talks about the thing which one talks about and no other?” That thing is distinct from other things; it exists, and if one talks about things that exist they talk truthfully. So, if someone talks in this way they talk the truth, and they will not mislead. So, how can one be misled?

This argument shows the impossibility of contradiction.

The next version runs:

If neither of us say anything (neither says the logos of the thing), we will not contradict.

If I say the logos of the thing and you do not, the argument implies there will be no contradiction.

A final implication is that if I say something and you say something, we will not contradict because if you say X and I say Y, we are talking about two different things, not the same thing, therefore there is no real contradiction, we are just talking differently.

This last one works because we switch from Legein meaning to talk about something to its other legitimate meaning, to name something. If the requirement is that one thing has one name, and we seem to contradict, then really we are talking of two things, not one:

- [“To clear up the paradox, it is sufficient to understand ti legein (to talk about something) here as if it were saying ‘to name something,’ a reading allowed by legein. For everything one talks about, there is a proper denomination, which is also the only proper one” (p.36).]

This necessitates that we believe in the hèn eph ’ hènos [one for each one] that Aristotle ascribes to Antisthenes, that is, one name designated to one thing. “And, if there is no error, it is because there is no Not-Being: the referent of a false phrase is not a nothingness, it is an object other than the one referred to” (p.36).

Lyotard notes that this way of avoiding contradiction is conducted by the two sophists slipping through the breach opened between Being and saying by Parmenides and the “neither Being nor Not-Being” of what is talked about in Gorgias (cf. Gorgias Notice).

So … “What can be said about the referent? ‘Before’ knowing whether what one says or will say about it is true or false, it is necessary to know what one is talking about [i.e. consensus, re: Plato Notice]. But how can it be known which referent one is talking about without attributing properties to it, that is, without already saying something about it? Antisthenes, like certain Megarans and like the Stoics later on, asks whether signification precedes or is preceded by designation. The thesis of nomination gets him out of the circle. The referent needs to be fixed; the name, as Kripke says, is a rigid designator that fixes the referent” (p. 36-7).

The problem: “Designation is not, nor can it be, the adequation of the logos to the being of the existent” (p.37). cannot have a one to one correspondence of word – being.

Names are not derived from or motivated by the named; to maintain this, one must know the essence of the thing before one names the thing, and how is this possible?

Antisthenes’ Nominalism: Nominalism is the belief that universals or ideas are mere names to which no reality corresponds; names mean nothing, what is real are the particular things named, esp. cf., William Ockham—Nominalism is an active designation, it creates, it is a Poiein: Greek, “to create,” it “isolates singularities in the undetermined…” (p.37).

The opposite of Antisthenes’ nominalism is the “Eponymy of the name” (cf., Gérard Gennette, Mimologiques, Paris, 1976, 11-37).

Eponymy: giving one’s name to something,

- e.g.: boycott, to abstain support as protest, is named after Charles C. Boycott, a land owner in Ireland ostracized by his tenets because of his high rent; mesmerize, to induce one into hypnosis, was named after Dr. Franz A. Mesmer, the Viennese doctor who used magnetism as a type of hypnotism; the poinsettia, the plants one often sees around the winter holidays, was named after Joel R. Poinsett, who established friendly commercial relations to Mexico, Argentina, and Chile, where the plants are native.

- Many products are named after their inventors or company owners, e.g., the beer Guinness after Arthur Guinness; the ice cream Ben and Jerry’s; Henry Ford’s cars.

Second Paradox (p.37): (from Aristotle on Antisthenes):

Concerns determination, specifically, logos as designator: Aristotle notes that “house” can mean all the matter that makes up a house, its bricks and such, or the final form of a house that makes them matter into a shelter.

If one speaks of a house as all the material that makes it up, one has not identified the ousia, the being, of the house. But, how can the being of the house be determined if not by all of its parts?

“Therefore the difficulty which was raised by the school of Antisthenes and other such uneducated people has a certain appropriateness. They stated that the ‘what it is’ … cannot be defined (for the definition so called is a long phrase …); but of what ‘sort’ … a thing, e.g. silver, is they thought it possible to explain, not saying what it is but that it is like tin. Therefore one kind of substance (ousia) can be defined and phrased …, i.e., the composite kind, whether it be the object of sense or of reason; but the primary elements of which this consists cannot be defined, since a definatory phrase … predicates something of something, and one part of this definition must play the part of the matter and the other that of form (Metaphysics VIII 1043 b 23-32)” (p. 37).

Lyotard notes the remarkable concession given to nominalism herein. But, it is essentially wrong because “… simples are not defined, they are named” (p.37). The simple, “whatever its grammatical nature, thus has the value of a name” (p.37).

Lyotard concludes by reinscribing Antisthenes’ problem into Aristotle’s vocabulary: “… one can perhaps say the ‘what its being was’ of a referent, but this referent would first have to be named ‘before’ any predication is made about it. The simple or the elementary is not a component of the object, it is its name and it comes to be situated as referent in the universe of the definitional phase. It is a simple – hence prelogical – logic which by itself is not pertinent with regard to the rules of truth (Wittgenstein, PhU: §49)” (p. 37).

An aside to further reflect/distract on names:

The Naming Of Cats

T.S. Eliot

T.S. Eliot

|

The Naming of Cats is a difficult matter,

It isn’t just one of your holiday games; You may think at first I’m as mad as a hatter When I tell you, a cat must have THREE DIFFERENT NAMES. First of all, there’s the name that the family use daily, Such as Peter, Augustus, Alonzo or James, Such as Victor or Jonathan, George or Bill Bailey All of them sensible everyday names. There are fancier names if you think they sound sweeter, Some for the gentlemen, some for the dames: Such as Plato, Admetus, Electra, Demeter-- But all of them sensible everyday names. But I tell you, a cat needs a name that’s particular, A name that’s peculiar, and more dignified, Else how can he keep up his tail perpendicular, Or spread out his whiskers, or cherish his pride? |

Of names of this kind, I can give you a quorum,

Such as Munkustrap, Quaxo, or Coricopat, Such as Bombalurina, or else Jellylorum- Names that never belong to more than one cat. But above and beyond there’s still one name left over, And that is the name that you never will guess; The name that no human research can discover-- But THE CAT HIMSELF KNOWS, and will never confess. When you notice a cat in profound meditation, The reason, I tell you, is always the same: His mind is engaged in a rapt contemplation Of the thought, of the thought, of the thought of his name: His ineffable effable Effanineffable Deep and inscrutable singular Name. |

~~ ~~ ~~ ... So ... ~~ ~~ ~~

(1) How many names are named?

(2) Explain (1).

(3) How does Aristotle’s Categories relate?

(4) Select a name herein and play a Wittgensteinian game (i.e., like Lyotard’s linkages) with it.

~~ ~~ ~~ ... * ... ~~ ~~ ~~

(1) How many names are named?

(2) Explain (1).

(3) How does Aristotle’s Categories relate?

(4) Select a name herein and play a Wittgensteinian game (i.e., like Lyotard’s linkages) with it.

~~ ~~ ~~ ... * ... ~~ ~~ ~~

|

Back to the Textual Analysis …

§55 * Partially a critique, partially an exposition of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus on proper names as “a metaphysical exigency and illusion…” (§55), in so far as a dogmatic position demands that proper names be fixed so that there is no possible error in them, an object cannot mistake its name (“Otherwise, says Dogmatism, how would true cognition be possible?” (§55)). According to Lyotard, Wittgenstein’s argument proceeds thus:

The Lyotardian interlocutor, like in the voice of Wittgenstein, adds:

Here is one early suggestion of advocacy, by Wittgenstein, for the Common Language / Ordinary Language Theory, which is not stated as a goal until Philosophical Investigations, wherein it is described as the language which we normally, ordinarily live by… PI, §108 uses the word gewöhnliche, which means “ordinary” or “normal,” and means the normal way in which we live, but uses Wöhnen instead of Lebens, thus, more a sense of “to dwell” than “to live,” thus suggesting it is the language like that with which we dwell. (Note the Heideggerian ring here, yet, this is the only place that Wittgenstein uses this particular verb in this way.) The issue that Lyotard takes with the theory of language wherein the proper name is rigidly fixed to the object, is that is proposes a picture theory of language (much like Descartes’ definition of an idea like an image of a thing) wherein the picture can be laid out over reality and used as its measure. Which, first, implies that reality is how the picture is, and second, raises the question of how one would go about verifying this commonality to be the case? There is a presupposition of form in order to present or represent the form of the picture, which requires a “biunivocal ‘correspondence’ (though feelers) between names and simple objects” (§55). These simples are neither true or false because they are less than objects of cognition. |

* An aside in relation to the point of §§55ff.: There is a synchronicity here between Lyotard and what we witness in Eastern traditions like Taoism and Zen Buddhism … especially poignant is to explore the ancient Chinese Taoist Chuang Tzu, and consider whether his form and content might provide a model for testimony of the inexpressible. This synchronicity concerns their conceptions of reality. For Chuang Tzu, reality is our desperate grasp on fixed logic and needs to be broken down so that we can experience the real reality of the unity of all things. Remember that the Tao is both the harmony of all things that always already is and the way things ought to be and how we ought to achieve it, that is, through a non-active activity. There is a truth underneath the misleading logic, but it is not so rigid. For Lyotard, reality also seems to be fixed, but is really not. The phrase happens and institutes a universe and establishes four instances of addressor, addressee, referent, and sense. This makes it sound as if reality is something constant; but this is not the case. Were reality fixed, which instant(s) containing silence could be deduced and the witness could be permitted to speak by negating the negative of the silence. Instead, reality is a lot more fluid. Recall that Lyotard has already demonstrated the flexibility between these positions. For example, Kant could be the one speaking, the one spoken to, the one whom I am speaking about, or even the meaning of what is being spoken about. This flexibility is especially clear in the case of deictics: this, here, now, there, etc. For example, when I say “now,” it is not the same as “now,” and when I speak of the now, I am not speaking of the now tied to either the first or second now’s. Each of the instances, and even deictics, however, could be understood by trying out various linkages of phases to determine what was meant (“chain of communication,” l’enchaînement §57). Also, there are many systems of cross-referencing words and meanings (cf., §49’s differentiation of systems).

Proper Names seemed to be the most fixed elements in language, existing in a tight linkage to the thing named wherein the name was given by another and meant nothing more than the thing named. That is, one does not go and validate the truth of a name, for a name is not a judgment or attribute that can be true or false, it simply names. Note that the more rigid nature of Proper Names permits language to both contain a deferral of meaning or arbitrariness between signified and signifier, and yet still function as a rather reliable means of communication. There are fixed elements, things that are stable, within the flux. Thus, names become quasi-deictics wherein their “rigidity is this invariability” (§57)--Kant is always Kant, regardless of which instance he occupies. Thus, names are unique. One of the points of the Antisthenes Notice was that there is a difference between naming something and talking about something (his obscuring this fact is what permitted him his paradox about the impossibility of contradiction). This difference between naming and talking about is what §§55 to 93 predominately concerns in addition to their mutual difference from showing something. But, before we see this, let’s think about this in terms of their founding of reality. The Ereignis, the phrase happening, institutes reality insofar as it institutes a phrase universe. But, what really does it give us and how are we to interpret this reality and verify it? In §56, Lyotard establishes that reality is given, but must also be established. |

§56

“Reality is ‘given’ in the universe of Jean’s first phrase (No. 49).” But, reality also has to be established, since deictics do not render referent into reality, as apparent in the cases of dreams, hallucinations, delirium, sensory errors, and idiolects (an individual’s dialectic, how a person speaks that is unique amongst other speakers of that language; but, this definition makes us fall into something like a private language debate, so, perhaps, this can also include groups, so that regional or ideological groups with shared slang, e.g., the “cat” was a jazz musician, not a feline). The reality is best established by other phrases as independent testimonies—these have the same referent, but are not immediately linked together. How is the referent known as the same? Well, same means that is can be contextualized and cross-referenced, e.g., through the systems of topography, chronology, anthroponymy, etc. When the referent is thus cross-referenced, however, it loses the current “givenness.” For example, if “This” becomes this record (this one, here, now, named such and such, etc.), “This” cannot then mean this cat. However, non-deictics, like “in the last row on the right-hand side of Pleyel hall” can be repeated and intend different referents.

§57

The context, the “chain of communication,” l’enchaînement, is important to understand the ‘origin’ of the name (no. 53). Lyotard refers to Kripke’s explanation of this. “The proper name is a designator of reality, like a deictic; it does not, any more than a deictic, have a signification, it is not, any more than a deictic, the abridged equivalent of a definite description or of a bundle of descriptions (Ibid. [Kripke, 1980: 91-3]). It is a pure mark of the designative function.” For proper names, the rigidity is that the name remains the same despite what it marks may switch from addressor to addressee to referent, predicate, etc. “Its rigidity is this invariability. The name designates the same thing because it remains the same.” (i.e. The child was baptized Kant, Kant signed a letter, that sounds like Kant…).

Note, that this permits language to both contain a deferral of meaning or arbitrariness between signified and signifier, and yet still function as a rather reliable means of communication. There are fixed elements, things that are stable, within the flux.

§58

“Names transform now into a date, here into a place, I, you, he into Jean, Pierre, Louis. Even silences can refer to gods (Kahn. 1978).” The name acts like a deictic, but, really, it is only a quasi-deictic because, in being in a fixed relation to an ‘as-if right here,’ it remains fixed throughout a sequence of phrases, whereas a true deictic (here) can be, in the next phrase, the opposite (there). “This fixed image becomes independent when the universe presented by the phrase in which it ‘currently’ has its place is named.”

§59

“The rigidity of nominal designators spreads to their relations.”

Nominal designators stand fixed and permit the fluidity of linkages to unfold around them. The here, “Rome,” and there, “Bologna,” as names, stand as quasi-fixed deictics with a gap between them, a gap as a “voyage” of all the heres and nows between them, from one to the other. That gap may be infinite, but the names remain fixed (so as to even permit the gap).

Colors: Perhaps the same rigidity proffered in the referentiality of names should be supposed for the logic of colors (cf., Gorgias Notice, for Lyotard, but, also, Wittgenstein on color)? The names of color, too, are given and do not supply information about that which they name. “Is this to say that This is red is more enigmatic than This is Rome?” (§59). This may have to be read as touched with sarcasm, for it would seem to argue that red is no more enigmatic than Rome, in that both are names that are fixed within a system, and despite the color naming an attribute rather than thing, it is more likely that it is only habit to presume the attribute more nebulous. This is problematic if we maintain a one-to-one correspondence theory, but, not necessarily, otherwise; the two function in parallel ways.

§60

“Networks of quasi-deictics formed by names of ‘objects’ and by names of relations designate ‘givens’ and the relations given between those givens, that is to say, a world. I call it a world because those names, being ‘rigid,’ each refer to something even when that something is not there; and because that something is considered to be the same for all phrases which refer to it be its name; and also because each of those names is independent of the phrase universes that refer to it, and in particular of the addressors and addressees presented in those universes (No. 56)” (§60).

(Also, in §68: “A system of names presents a world.”)

“This is not to say that something which has the same name in several phrases has the same meaning. Different descriptions can be made of it, and the question of its cognition is opened and not closed by its name” (§60). Thus, names are subject to Antisthenes’ proclamation of one-to-one correspondence; this is valid because “reality is not established by ostension alone” (§60).

Note the importance of this: Even when ostension is used, validly, ostension signifies outside of current givenness to a world more fixed, a world of names beyond and independent of ostension. (i.e., thus another argument against the revisionist who demands that the witness ‘show him’ the gas chambers gassing.)

§61

“A cognitive phrase is validated thanks to another phrase, an ostensive one or one which displays.”

- But, this showing as verification still takes the deictic outside of its current-ness because it shows something in specificity, this red flower here, e.g., this red rose in Hiram’s rose garden on June 21, 2006.

- Cognitive phrases: describes, defines red has wavelengths of 650-750 millimicrons of radiation.

- Ostensive phrases: shows this red flower, here

- (from before, we can add: (De)Nominative phrases: name)

§62

Once the ostensive is freed from the current-ness of the deictics, it can be replaced with any and every example of a red flower and be the referent of the cognitive phrase that defines red as having wave lengths of a certain size.

Red flowers become the archive of examples that validate the description—even as it maintains some degree of cross-referencing; the ‘millimicrons’ of the description also maintains some degree, too. Thus…

“Description cannot free itself from denomination, reference cannot be reduced to sense (Tarski, 1944, 344). For denomination to have only a referential function is to open description (cognition) up to the course of an endless refinement. But what does it open reality up to?”

§63

“The name ‘rigidly’ designates across phrase universes, it is inscribed in networks of names which allow for the location of realities, but it does not endow its referent with a reality.” That is, even when the name rigidly designates across phrase universes, its referent does not have to be judged real or true.

- e.g., “Utopia” is a rigid name, although we cannot find it; “phlogiston” and “hydrogen” are names, but only the latter has a “real” referent, nevertheless, both stand rigid across universes. But, the “real” designation is not necessarily determined by seeing any of these… such ostension is not a test for reality.

“This is Caesar” is a nominative phrase, not an ostensive one. This can take place before Caesar the man, his portrait, or a dog named Caesar: “…to name the referent is not the same as to show its ‘presence.’ To signify is one thing, to name another, and to show still another.”

§64

Critique of ‘showing.’ “To show that an x is a case of the cognitive phrase x is P is to present x as real. Because the ostensive phrase presents its referent as given, it can validate a description with cognitive phrases. For something to be given means both that its referent is there and that it is there even when it is not shown. It would exist even without its being phrased, ‘extralinguistically’ (Nos. 47, 48)” (§64).

Because the ostensive phrase goes beyond its act of ostension and enters a network of signification, one would have to accept, in order for it to ever be valid, that the ostensive proof is proof even when it is not in its current givenness. The referent must subsist through time and be, even when not being named or seen.

While this redeems ostensive evidence, to a degree, Lyotard goes on to show us that what we automatically presume to be the most solid form of evidence (“Look, see!”), is also the weakest form of evidence by thus opening itself up to two main critiques:

“–It is easy then for an opponent to refute whoever affirms the reality of a referent by enclosing him in a dilemma: either the shown referent is merely what is shown, and it is not necessarily real (it might be an appearance, etc.); or else, it is more than what is shown, and it is not necessarily real (how can one know that which is not there is real?). This dilemma is the one that assails all philosophies based on showing (Descombes, 1981a)” (§64).

The escape of the dilemma is difficult and its most common attempt ends up provoking a new problem: “They generally elude the dilemma through recourse to the testimony of some infallible third party, to whom what is hidden from the ‘current’ addressee of the ostensive phrase is supposedly absolutely (constantly) revealed. There is little difference in this regard between the God of the Cartesians and the pre-predicative cogito of the phenomenologists. Both groups admit an entity who is in a state of ‘cosmic exile’ (McDowell in Bouveresse, 1980, 896)” (§64).

Proof by recourse to the revelation of a sort of presence in absence. This is a stand critique of phenomenology (and most of the tradition) by numerous postmodernists; besides Lyotard, this critique surfaces most notably in Derrida’s Of Grammatology. It is often lobbed against religious foundations, innate ideas of God, and Husserl’s reliance on the veracity of monologue, and, in general, phenomenology’s recourse to and reliance on “presence.”

§65

“Real or not, the referent is presented in the universe of a phrase, and it is therefore situated in relation to some sense” (§65). Thus, even if we are speaking of phlogiston, it has a sense, Sinn, a meaning, even if it is not real.

There must be a fourth phrase: The fourth phrase would state that the signified referent, named referent, and the shown referent are all the same.

§66

The identity of these referent is not now determined and fixed; it must be re-established. “It is therefore not sense which can supply the identity of two referents, but the empty ‘rigidity’ of the name.” “That is why reality is never certain …”

§67

“The reality of this (of what is shown by an ostensive phrase) is necessary, for example, for the validation of a cognitive phrase whose referent beats the same names as this. That reality is not a property attributable to the referent answering to the name. The ontological argument is false, and that seems to suffice to forbid one from following the speculative way, which requires am equivalence between sense and reality (Result section).” Also, it is not Kantian. “Reality cannot be deduced from sense alone, no more than it can from ostension alone. It does not suffice to conclude that the two are required together.” Instead, one must understand how the ostensive and the descriptive come together: this is to be understood through understanding the role of the name, “The name holds the position of linchpin.” “The name fills the function of linchpin because it is an empty and constant designator. Its quasi-deictic import is independent of the phrase in which it currently figures, and it can accept many semantic values because it excludes only those that are incompatible with its place in the network of names …”

§68

So … is the name like Kant’s schema in the Analytic of Judgment? “It too serves to articulate the sensible with the concept.” But … Lyotard argues … “But, first, the schema operates exclusively in the framework of the validation of a cognitive, but not the name. Second, in critical reflection, the schema requires its deduction as an a priori necessary for cognition (in the Kantian sense). Here, I am doubtlessly deducing the function of names from the assertion of reality, but I cannot deduce their singularity: Rome, Auschwitz, Hitler … That I can only learn. To learn names is to situate them in relation to other names by means of phrases.” “This is not a schema like a number. A system of names presents a world. The universes presented by the phrases that group names are signified fragments of that world.”

Critique of ‘showing.’ “To show that an x is a case of the cognitive phrase x is P is to present x as real. Because the ostensive phrase presents its referent as given, it can validate a description with cognitive phrases. For something to be given means both that its referent is there and that it is there even when it is not shown. It would exist even without its being phrased, ‘extralinguistically’ (Nos. 47, 48)” (§64).

Because the ostensive phrase goes beyond its act of ostension and enters a network of signification, one would have to accept, in order for it to ever be valid, that the ostensive proof is proof even when it is not in its current givenness. The referent must subsist through time and be, even when not being named or seen.

While this redeems ostensive evidence, to a degree, Lyotard goes on to show us that what we automatically presume to be the most solid form of evidence (“Look, see!”), is also the weakest form of evidence by thus opening itself up to two main critiques:

“–It is easy then for an opponent to refute whoever affirms the reality of a referent by enclosing him in a dilemma: either the shown referent is merely what is shown, and it is not necessarily real (it might be an appearance, etc.); or else, it is more than what is shown, and it is not necessarily real (how can one know that which is not there is real?). This dilemma is the one that assails all philosophies based on showing (Descombes, 1981a)” (§64).

The escape of the dilemma is difficult and its most common attempt ends up provoking a new problem: “They generally elude the dilemma through recourse to the testimony of some infallible third party, to whom what is hidden from the ‘current’ addressee of the ostensive phrase is supposedly absolutely (constantly) revealed. There is little difference in this regard between the God of the Cartesians and the pre-predicative cogito of the phenomenologists. Both groups admit an entity who is in a state of ‘cosmic exile’ (McDowell in Bouveresse, 1980, 896)” (§64).

Proof by recourse to the revelation of a sort of presence in absence. This is a stand critique of phenomenology (and most of the tradition) by numerous postmodernists; besides Lyotard, this critique surfaces most notably in Derrida’s Of Grammatology. It is often lobbed against religious foundations, innate ideas of God, and Husserl’s reliance on the veracity of monologue, and, in general, phenomenology’s recourse to and reliance on “presence.”

§65

“Real or not, the referent is presented in the universe of a phrase, and it is therefore situated in relation to some sense” (§65). Thus, even if we are speaking of phlogiston, it has a sense, Sinn, a meaning, even if it is not real.

- Descriptive:

- “The empire has a capital for its political center.”

- “…in an internment camp, there was mass extermination by chambers full of Zyklon B…”

- Nominative:

- “This capital is called Rome.”

- “…that camp is called Auschwitz…”

- Ostensive:

- “Here is Rome.”

- “… here it is …”

There must be a fourth phrase: The fourth phrase would state that the signified referent, named referent, and the shown referent are all the same.

- (This would be verification, permit the referent to be real if it is named as the same in each of these: signified (descriptive), named (nominative), and shown (ostensive), and then given a fourth prhase that demonstrates the same-ness amongst them all… and, even after this validation, it is not fixed, it must be re-established each time, as the next section states.)

§66

The identity of these referent is not now determined and fixed; it must be re-established. “It is therefore not sense which can supply the identity of two referents, but the empty ‘rigidity’ of the name.” “That is why reality is never certain …”

§67

“The reality of this (of what is shown by an ostensive phrase) is necessary, for example, for the validation of a cognitive phrase whose referent beats the same names as this. That reality is not a property attributable to the referent answering to the name. The ontological argument is false, and that seems to suffice to forbid one from following the speculative way, which requires am equivalence between sense and reality (Result section).” Also, it is not Kantian. “Reality cannot be deduced from sense alone, no more than it can from ostension alone. It does not suffice to conclude that the two are required together.” Instead, one must understand how the ostensive and the descriptive come together: this is to be understood through understanding the role of the name, “The name holds the position of linchpin.” “The name fills the function of linchpin because it is an empty and constant designator. Its quasi-deictic import is independent of the phrase in which it currently figures, and it can accept many semantic values because it excludes only those that are incompatible with its place in the network of names …”

§68

So … is the name like Kant’s schema in the Analytic of Judgment? “It too serves to articulate the sensible with the concept.” But … Lyotard argues … “But, first, the schema operates exclusively in the framework of the validation of a cognitive, but not the name. Second, in critical reflection, the schema requires its deduction as an a priori necessary for cognition (in the Kantian sense). Here, I am doubtlessly deducing the function of names from the assertion of reality, but I cannot deduce their singularity: Rome, Auschwitz, Hitler … That I can only learn. To learn names is to situate them in relation to other names by means of phrases.” “This is not a schema like a number. A system of names presents a world. The universes presented by the phrases that group names are signified fragments of that world.”

- A Little More on §§67-68:

- The Proper Name is a “linchpin” (§67) because it serves as a quasi-fixed post around which possible phrases can gather; it is both empty and constant, at once. It evades the problems of a one-to-one correspondence theory between signified and signifier, yet, permits something fixed enough for a context to form and communication to happen.

- Is it, then, like Kant’s schema? (§68):

- This is a reference to Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason’s Analytic of Judgment. A “schema” is a rule of synthesis; a synthesis is the mental act of putting together different representations and grasping what is manifold in them in one act of knowing. How we put these together is by aid of “the categories,” which are pure concepts; for Kant, there are four meta-categories that each have three subcategories: Quantity (Universal, Plurality, Totality); Quality (Reality, Negation, Limitation); Relation (of Inherence/Subsistence, of Causality/Dependence, of Community); and Modality (Possibility or Impossibility, Existence or Non-Existence, Necessity, or Contingency). These categories are ways by which we synthesize representations. “The Schematism,” then, is a rule by which a category is related to the mental image of an object via the imagination and through the form of time.

- This is a reference to Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason’s Analytic of Judgment. A “schema” is a rule of synthesis; a synthesis is the mental act of putting together different representations and grasping what is manifold in them in one act of knowing. How we put these together is by aid of “the categories,” which are pure concepts; for Kant, there are four meta-categories that each have three subcategories: Quantity (Universal, Plurality, Totality); Quality (Reality, Negation, Limitation); Relation (of Inherence/Subsistence, of Causality/Dependence, of Community); and Modality (Possibility or Impossibility, Existence or Non-Existence, Necessity, or Contingency). These categories are ways by which we synthesize representations. “The Schematism,” then, is a rule by which a category is related to the mental image of an object via the imagination and through the form of time.

- Is it, then, like Kant’s schema? (§68):

- The Proper Name is a “linchpin” (§67) because it serves as a quasi-fixed post around which possible phrases can gather; it is both empty and constant, at once. It evades the problems of a one-to-one correspondence theory between signified and signifier, yet, permits something fixed enough for a context to form and communication to happen.

- Lyotard responds that the ‘linchpin’ nature of the proper name is not exactly the same as Kant’s schema—although, there is the implication that it is similar. He states the differences: (1) The schema validates a cognitive [definition or description], not a name; (2) the schema requires a priori its deduction for cognition (§68). In contrast, one does deduce the function of names from the assertion of reality, but one cannot deduce their singularity. To know the singularity of names, one must learn it. “To learn names is to situate them in relation to other names by means of phrases” (§68).

- “A system of names presents a world. The universes presented by the phrases that group names are signified fragments of that world” (§68). In other words, the conglomeration of names presents a world wherein there are many facets. Just as our world includes the U.S.A., Brazil, South Africa, and France, and each country includes its people, its land, its political system, its languages, and so forth, the world made of the system of names includes topographic and chronological systems, proper names and deictics, and so forth. Learning these facets and how they relate requires context (he offers the example of how we learn “white”—through snow, sheet, paper—and their associated senses—to slide over, to sleep in, to write on—and their possible ostensions—there, that, etc.,—whose validations refer to other names—You know, as at Chamonix … (§68)). However, no matter how much contextualization is done, there are still inherent slippages at the heart of ontological phrases (referents, names, deitics, etc.).

§69

“How is sense attached to the name when the name is not determined by the sense nor the sense by the name? Is it possible to understand the linkage of name and sense without resorting to the idea of an experience? An experience can be described only be means of a phenomenological dialectic …” Phenomenology permits understanding the “possible in the constitution of reality.” Perspectival perceiving expresses reality not just as “x is,” but also as “x is not.” “To the assertion of reality, there corresponds a description inconsistent with regard to negation. This inconsistency characterizes the modality of the possible.”

§70

“The ostensive phrase, that is, the showing of the case, is simultaneously an allusion to what is not the case. A witness, that is, the addressor of an ostensive phrase validating a description, attests (or thinks he or she is attesting) through this phrase to the reality of a given aspect of a thing. But, he or she should by that very score recognize that other aspects which he or she cannot show are possible. He or she has not seen everything. If he or she claims to have seen everything, he or she is not credible. If he or she is credible, it is insofar as he or she has not seen everything, but has only seen a certain aspect. He or she is thus not absolutely credible. Which is why he or she falls beneath the blows of the dilemma (No. 8): either you were not there, and you cannot bear witness; or else you were there, you could not therefore have seen everything, and you cannot bear witness about everything. It is also upon this inconsistency with regard to negation that dialectical logic relies in regulating the idea of experience.”

§71

“The idea of an experience presupposes that of an I which forms itself (Bildung) by gathering in the properties of things that come up (events) and which constitutes reality by effectuating their temporal synthesis. It is in relation to this I that events are phenomena. Phenomenology derives its name from this. But the idea of the I and that of experience which is associated with it are not necessary for the description of reality. They come from the subordination of the question of truth to the doctrine of evidence.” The neutralization of reality can have two incarnations: one, is Gorgias’ nihilism (“neither Being nor Not-Being”) (although this leads to “demonstrations say everything,” which opens the way for philosophy of argumentation and analysis of phrases) and, two, the monotheistic and monopolitical principle which highlights the finitude of the witness deprived of absolute jouissance; such is only permitted the “absolute witness (God or Caesar).” “The idea of experience combines the relative with the absolute. Dialectical logic maintains the experience and the subject of the experience within the relative. Speculative logic endows them with the property of accumulation (Resultat, Erinnerung) and places them in a continuity with the final absolute (Hegel Notice).”

§72

The Cogito is a deictic; thus, while it is used to conclude existence, it must be re-established; “…the I of I think and the I of I am require a synthesis.” Thus, Descartes qualifies that ‘whenever I utter it, it is true;’ but, there is no guarantee that it is from one ‘whenever’ to the next. “A subject is thus not the unity of ‘his’ or ‘her’ experience. The assertion of reality cannot spare itself the use of at least a name. It is through the name, an empty link, that I at instant t and I at instant t + 1 and be linked to each other and to Here I am (ostension). The possibility of reality shows itself and signifies itself in an experience.”

“How is sense attached to the name when the name is not determined by the sense nor the sense by the name? Is it possible to understand the linkage of name and sense without resorting to the idea of an experience? An experience can be described only be means of a phenomenological dialectic …” Phenomenology permits understanding the “possible in the constitution of reality.” Perspectival perceiving expresses reality not just as “x is,” but also as “x is not.” “To the assertion of reality, there corresponds a description inconsistent with regard to negation. This inconsistency characterizes the modality of the possible.”

- This section reveals Lyotard’s support and critique of phenomenology.

- Phenomenological awareness of the world is that we see potential, as well as what is actual. Because reflection is, integrally, a part of the very activity of consciousness, when we see the table, we also “see” its left, right, back side, bottom, and top, even if these are technically concealed from our line of vision. This is Perspectival Viewing: a thing may present us its one horizon, but our mind naturally and automatically fills in all the others … they may be right or wrong, we can always make mistakes (the street may be a screen set, instead of having a real backside). Similarly, is the mass of possible phrases conjured by the presentation of one phrase. Lyotard says that the aspect of phenomenology he particularly wishes to retain is this, “that is includes the possible in the constitution of reality” (§69) and that “Reality is not expressed therefore by a phrase like: x is such, but by one like: x is such and is not such…” (§69). (He refers us forward to Nos. 81, 83.) “The ostensive phrase, that is, the showing of the case, is simultaneously an allusion to what is not the case” (§70).

§70

“The ostensive phrase, that is, the showing of the case, is simultaneously an allusion to what is not the case. A witness, that is, the addressor of an ostensive phrase validating a description, attests (or thinks he or she is attesting) through this phrase to the reality of a given aspect of a thing. But, he or she should by that very score recognize that other aspects which he or she cannot show are possible. He or she has not seen everything. If he or she claims to have seen everything, he or she is not credible. If he or she is credible, it is insofar as he or she has not seen everything, but has only seen a certain aspect. He or she is thus not absolutely credible. Which is why he or she falls beneath the blows of the dilemma (No. 8): either you were not there, and you cannot bear witness; or else you were there, you could not therefore have seen everything, and you cannot bear witness about everything. It is also upon this inconsistency with regard to negation that dialectical logic relies in regulating the idea of experience.”

§71

“The idea of an experience presupposes that of an I which forms itself (Bildung) by gathering in the properties of things that come up (events) and which constitutes reality by effectuating their temporal synthesis. It is in relation to this I that events are phenomena. Phenomenology derives its name from this. But the idea of the I and that of experience which is associated with it are not necessary for the description of reality. They come from the subordination of the question of truth to the doctrine of evidence.” The neutralization of reality can have two incarnations: one, is Gorgias’ nihilism (“neither Being nor Not-Being”) (although this leads to “demonstrations say everything,” which opens the way for philosophy of argumentation and analysis of phrases) and, two, the monotheistic and monopolitical principle which highlights the finitude of the witness deprived of absolute jouissance; such is only permitted the “absolute witness (God or Caesar).” “The idea of experience combines the relative with the absolute. Dialectical logic maintains the experience and the subject of the experience within the relative. Speculative logic endows them with the property of accumulation (Resultat, Erinnerung) and places them in a continuity with the final absolute (Hegel Notice).”

§72

The Cogito is a deictic; thus, while it is used to conclude existence, it must be re-established; “…the I of I think and the I of I am require a synthesis.” Thus, Descartes qualifies that ‘whenever I utter it, it is true;’ but, there is no guarantee that it is from one ‘whenever’ to the next. “A subject is thus not the unity of ‘his’ or ‘her’ experience. The assertion of reality cannot spare itself the use of at least a name. It is through the name, an empty link, that I at instant t and I at instant t + 1 and be linked to each other and to Here I am (ostension). The possibility of reality shows itself and signifies itself in an experience.”

- Here, we have see more of the critique of phenomenology:

- Phenomenology’s premise is the co-creation of meaning by the active engagement of the subject and world: the world gives itself to me as I give myself to it, and in this co-givenness, meaning is created. Meaning, then, is after the establishment of the subject and object. This reliance upon experience requires an “I” who forms itself by gathering up events and constituting them into reality by means of a temporal synthesis (§71). Events are phenomena (we can experience and describe) by fact of this “I.” “But the idea of the I and that of experience which is associated with it are not necessary for the description of reality” (§71). “This idea of experience,” he says, “combines the relative and the absolute” (§71)—because the witness is permitted to see what is, that one horizon that is relative to her, and the absolute, all the others filled in by the reflective aspect of consciousness (which he calls something like a God’s eye-view).

- The problem is that the “I” is, itself, a product of a synthesis (§72). So, the “I” cannot render reality, but reality must somewhat pre-exist in possibility in order to permit the I and the reality to be. (Just as we cannot fall prey to thinking the “I” owns and controls language, we cannot fall prey to thinking the “I” is a subsistent and consistent given.) Hence:

§73

“It follows that reality does not result from an experience. This does not at all prevent it from being described from the standpoint of an experience. The rules to respect in undertaking this description are those of speculative logic (Hegel Notice) and also those of a novelistic poetics (observing certain rules that determine narrative person and mode) (Genette, 1972: 161-2; 243-45). This description, though, has no philosophical value because it does not question its presuppositions (the I or the self, the rules of speculative logic).” But, Lyotard continues, that the presuppositions themselves are not necessary in the assertion of the reality of a referent. There are two other necessities for that assertion: first, that the referent profits from the permanence of the name that names it (“the rigidity of the named is the shadow projected by the rigidity of the designator, the name”), and, second, that the named referent is real when it is also the possible case of an unknown sense, which seems to contradict the former requirement. “In the assertion of reality, the persistence of the referent (It’s really x, it is recognized) is combined with the event of a sense (Well! X is also this, it is discovered).”

§§74-7

The number and specific sense of a referent cannot be determined a priori. No totality can be proven. The inflation of senses can be limited by logical rules and their application toward validating cognitive phrases [historical inquiry]. The inflation of sense attached to names cannot be absolutely halted because: (a) “…names are not the realities to which they refer, but empty designators which can only fulfill their current ostensive function if they are assigned a sense whose referent will be shown to be the case by an ostensive phrase” (76). “One does not prove something, one proves that a thing presents the signified property” (76). And (b) “… phrases under the cognitive regimen, which undergo the sifting by truth conditions, do not have a monopoly on sense. They are ‘well formed.’ But poorly formed phrases are not absurd” (77).

§§78-79:

Translation versus transcription

§88-92:

“Reality is not a matter of the absolute eyewitness, but a matter of the future” (§88).