Michel Foucault’s The Order of Things

Michel Foucault’s The Order of Things, in A&S, pp. 439-454.

... On the Preface ...

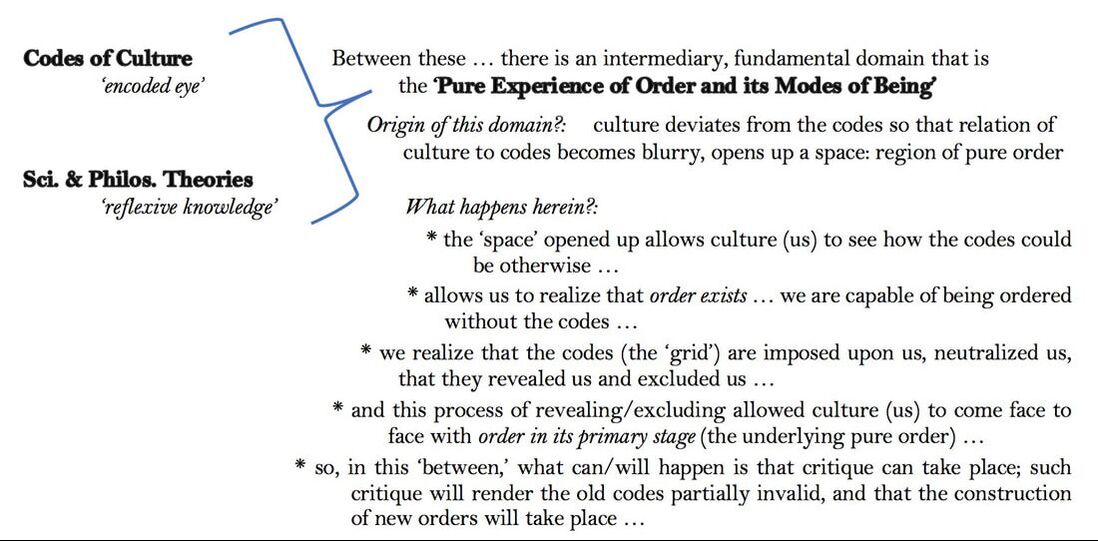

Establishing the basis of the Analysis of Pure Experience of Order ...

... this is the fundamental domain between the 'codes of culture' and the 'scientific and philosophical theories' he describes ...

... On the Preface ...

Establishing the basis of the Analysis of Pure Experience of Order ...

... this is the fundamental domain between the 'codes of culture' and the 'scientific and philosophical theories' he describes ...

So …

Foucault’s present study, “Las Meninas,” is an attempt to analyze that experience (the ‘in between’ described above).

- Carefully note this “attempt to analyze” … quite literally, the rest of the reading is his archeological work getting into the ‘site’ of Diego Veláquez’s 1656 painting Las Meninas (‘the ladies in waiting’)—read this ‘getting into’ the painting as a demonstration of what all the above means; pay close attention to the how throughout.

This attempt will seek to show:

- * what way of language, categories, and exchange are formed

- * what way of culture manifests order and bears out modalities of valuing

- * what modes of order given posit the base of knowledge

What he is seeking throughout are the conditions of possibility

- * i.e., not what is, but what is it that permits the possibility of what is to be what it is …

What he is doing, then, is an archeology

- * i.e., a theoretical work that parallels the work of archelogy (e.g., a study of human history & prehistory via excavation of sites, analyses of artifacts, examinations of diverse physical remains), and:

- i.e., a theoretical work that shares its essence with that of archelogy if we consider the etymology:

- Archelogy comes from archéologie (French, 16th c.: ‘ancient history’), which comes from arkhaiologia (Greek, ‘study of ancient things), which comes from arkhaios- [(‘ancient, primeval’), which comes from arkhe (‘beginning’)] + -ology [(‘study of’), itself from logos (‘reason, word’)]

- So … archelogy’s etymological roots show that it is the causal reasoning/saying of arkhe (arché), whose ‘beginning’ is better understood as the principle, cause, origin, reason, source, sum, and whole … it is that from which things come to be and that which is in its dynamism and that to which all is … so, the beginning, being, and end of all that is! This helps us understand Foucault because he is seeking the “conditions of possibility,” so he is working like an archeologist on site to trace back the what is given so as to come to know the most primordial thought, what is itself before all else (hence free of encodings of culture and reflexive theories), causes all else (is creative, gives rise to all that is and can give rise to what isn’t but could be), and still, by these traces we study, is what is (hence, not ‘orders’ that are fiction, but realities that are simply potential or repressed or unexplored or veiled over).

- Archelogy comes from archéologie (French, 16th c.: ‘ancient history’), which comes from arkhaiologia (Greek, ‘study of ancient things), which comes from arkhaios- [(‘ancient, primeval’), which comes from arkhe (‘beginning’)] + -ology [(‘study of’), itself from logos (‘reason, word’)]

... Before moving into his archeological analysis,

his doing of the analysis of the experience of pure order,

a little background on the work under question ...

Las Meninas:

Background on the painter and about the painting … note how all of this speaks to the ‘codes of culture’ and the ‘sci/phi theories’ … think about how these/this information gives an order, and how the ‘pure’ order we are seeking is between these, hence, something other than the following …

Diego Velázquez, Self Portrait, ca. 1640

Diego Velázquez, Self Portrait, ca. 1640

On Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Veláquez (b.1599 in Seville, d.1660 in Madrid):

Spanish painter—almost always gifted with qualifications of ‘most admired,’ ‘most successful,’ ‘greatest,’ etc.—employed by the court of King Philip IV in Spain’s ‘golden age,’ Veláquez heavily engaged Baroque style, painted historical and cultural scenes as well as portraits, almost always noted as ‘miraculous,’ ‘conveying pure truth,’ ‘capturing reality,’ ‘indistinguishably life-life,’ etc.. He was influenced by Caravaggio (notably adopting his naturalism), Venetian paintings and Peter Paul Rubens (notably honing their use of perspective and mastering the rendering of nudes—the realism herein led to his notable works of court life, including dwarfs and jesters painted with such clarity they record their suffering amidst their ensuing hilarity that can continue to shock). Around 1650, his sensational showing of a portrait of his assistant (so lifelike) led to his being granted sole permission to paint Pope Innocent X (which was then “looked upon as a miracle” and copied by all the artists of the day). His work Las Meninas is one of his latest paintings and is considered by an overwhelming many to be his freest and most spectacular work. After his death, since most of his works were for kings and the pope, they were not seen by many. However, Antonio Palomino’s notable history of Spanish painters (1724) devoted a whole section to Veláquez, which established him as an unquestionable master (and his work Las Meninas as his masterpiece). Then, when Napoleon went about his warring in the 1800’s, the work was freed and spread through Northern Europe, allowing many far and wide to see it, hence his impact has been strongest on artists stating in the 19th c.

Spanish painter—almost always gifted with qualifications of ‘most admired,’ ‘most successful,’ ‘greatest,’ etc.—employed by the court of King Philip IV in Spain’s ‘golden age,’ Veláquez heavily engaged Baroque style, painted historical and cultural scenes as well as portraits, almost always noted as ‘miraculous,’ ‘conveying pure truth,’ ‘capturing reality,’ ‘indistinguishably life-life,’ etc.. He was influenced by Caravaggio (notably adopting his naturalism), Venetian paintings and Peter Paul Rubens (notably honing their use of perspective and mastering the rendering of nudes—the realism herein led to his notable works of court life, including dwarfs and jesters painted with such clarity they record their suffering amidst their ensuing hilarity that can continue to shock). Around 1650, his sensational showing of a portrait of his assistant (so lifelike) led to his being granted sole permission to paint Pope Innocent X (which was then “looked upon as a miracle” and copied by all the artists of the day). His work Las Meninas is one of his latest paintings and is considered by an overwhelming many to be his freest and most spectacular work. After his death, since most of his works were for kings and the pope, they were not seen by many. However, Antonio Palomino’s notable history of Spanish painters (1724) devoted a whole section to Veláquez, which established him as an unquestionable master (and his work Las Meninas as his masterpiece). Then, when Napoleon went about his warring in the 1800’s, the work was freed and spread through Northern Europe, allowing many far and wide to see it, hence his impact has been strongest on artists stating in the 19th c.

On Las Meninas

[‘the ladies in waiting’] (1656, oil on canvas, 10.4’ x 9.1’, Prado):

- “[Las Meninas] suggests that art, and life, are an illusion” (Dawson Carr, Painting & Reality, 50).

- “[Las Meninas represents] the theology of painting” (Luca Giordano, a peer Baroque painter).

- “[Las Meninas is] the true philosophy of the art” (Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1827).

- “[Las Meninas is] perhaps the most searching comment ever made on the possibilities of the easel painting” (Honour & Flemming, A World History of Art, 447).

- “Las Meninas has one meaning that is immediately obvious to any viewer: it is a group portrait set in a specific location and peopled with identifiable figures undertaking comprehensible actions.[2] The painting’s aesthetic values are also evident: the setting is one of the most credible spaces depicted in western art; the composition combines unity and variety; the remarkably beautiful details are divided across the entire pictorial surface; and finally, the painter has taken a decisive step forward on the path to illusionism, which was one of the goals of European painting in the early modern age, given that he has gone beyond transmitting resemblance in order to successfully achieve the representation of life or animation.[3] However, as is habitual with Velázquez, in this scene in which the Infanta and the court servants pause in their actions on the arrival of the King and Queen, there are numerous underlying meanings that pertain to different fields of experience and which co-exist[4] in one of the masterpieces of western art that has been the subject of the most numerous and most varied interpretations” (from Prado’s official description).

[2] In relation to Foucault, note: here is an account of meaning that can open up ‘cultural codes’ … it is objective, factual, yet however we fill this out, it will be in accord with our cultural conventions, e.g., it is right and common for important people to have portraits made; they are figures of royalty; etc.

[3] In relation to Foucault, note: here is an account that gets closer to a scientific/philosophical theory … close because it opens up the theoretically common features aesthetics delineates as the content for aesthetic judgment (that it is art and its value as art).

[4] In relation to Foucault, note: here is an idea hinting at why he may have chosen this piece (beyond the excessive cultural codes and philosophic theories about it!): that Velázquez himself operated within the intent to and created an object that carries underlying multiplicity of meanings from and about different fields in simultaneity.

[3] In relation to Foucault, note: here is an account that gets closer to a scientific/philosophical theory … close because it opens up the theoretically common features aesthetics delineates as the content for aesthetic judgment (that it is art and its value as art).

[4] In relation to Foucault, note: here is an idea hinting at why he may have chosen this piece (beyond the excessive cultural codes and philosophic theories about it!): that Velázquez himself operated within the intent to and created an object that carries underlying multiplicity of meanings from and about different fields in simultaneity.

... Now ... Begin to Move into Foucault's Analysis (pp.443-54) ...

Several Key Conceptual Points in Foucault’s Analysis:

§1 (pp.443-47):

He begins with the painter (Veláquez’s self-representation within the painting, the painter partially behind the canvas, the furthest left figure). Note the reciprocal relation between the painter’s hand and gaze—each waits for the other, what they will yield is the whole volume of the painting that remains concealed but causes the entirety of the painting we see. This yield, however, has its “subtle system of feints”—feints being those maneuvers designed to distract or mislead, to give the impression some thing X will come to be when Y, or that nothing actually will—including his positioning (mirror-reversed, to our left, he appears at the far right of his canvas, but it is his far left to his canvas), suggesting the capture of an instant, a quick moment when he has appeared from behind his canvas, and the moment he begins to paint again, he will vanish from our sight. Further oscillation suggested by his being partly in shadow, in light (in-between, just as his hand and gaze hover between action)—when his ‘light’ comes (his hand can make the painting come forth again), he will vanish from our sight (behind his canvas, back to work): “He rules at the threshold of those two incompatible visibilities” (443).

Several Key Conceptual Points in Foucault’s Analysis:

- Lines of Sight: relation of seer/seen; reciprocity between; complex network of meanings in exchange; spiral shell (cycle of representation); chiasmus (X construction); gaps

- Bright/Dark: how vision relates to light; leading eye; signaling symbolic meaning;

- Mirror/Window: how reflect/illuminate, adding symbolic meaning beyond real; duplication, revelation;

- Identities of figures: proper names; language-painting relationship; erasure of names;

§1 (pp.443-47):

He begins with the painter (Veláquez’s self-representation within the painting, the painter partially behind the canvas, the furthest left figure). Note the reciprocal relation between the painter’s hand and gaze—each waits for the other, what they will yield is the whole volume of the painting that remains concealed but causes the entirety of the painting we see. This yield, however, has its “subtle system of feints”—feints being those maneuvers designed to distract or mislead, to give the impression some thing X will come to be when Y, or that nothing actually will—including his positioning (mirror-reversed, to our left, he appears at the far right of his canvas, but it is his far left to his canvas), suggesting the capture of an instant, a quick moment when he has appeared from behind his canvas, and the moment he begins to paint again, he will vanish from our sight. Further oscillation suggested by his being partly in shadow, in light (in-between, just as his hand and gaze hover between action)—when his ‘light’ comes (his hand can make the painting come forth again), he will vanish from our sight (behind his canvas, back to work): “He rules at the threshold of those two incompatible visibilities” (443).

- n.b.: all the in-betweens here … the space or gap of dynamic, roiling potential …

|

... Now ... look at how the painter is looking: it is right at the subject he is painting, at once, it is right at us. “The spectacle he is observing is thus doubly invisible” (443), for it is out of the frame of the painting, and it is right at us, that ‘self’ which we lose sight of as soon as we look at something—yet, we can’t fail to see this invisibility. The back of the canvas we see—seeing nothing of the painting on canvas on which he is painting—“reconstitutes in the form of a surface the invisibility in depth pf what the artist is observing” (the canvas’ first function of the back of the canvas). His line of sight transgresses the frame of the actual painting to connect to us, “and links us to the representation of the picture” (444).

|

“Seen or Seeing?” (444)—note the “virtual triangle” (444): the painter’s eye as the top point, to the one base point of the image we cannot see getting painted on the painter’s canvas, to the other base point of the object he is painting which is simultaneously where we stand.

When we stand before it—the spectators—the painter’s eyes take hold of us, force us to enter the picture “a place at once privileged and inescapable” (444), where we see our invisibility made visible to the painter and transposed into that painting he is making, which we will never see … “a marginal trap” (445) … from the ‘virtual triangle’ to the far right of the painting where “the picture is lit by a window” (445) ...

“so that the flood of light streaming through it bathes at the same time, and with equal generosity, two neighboring spaces, overlapping but irreducible: the surface of the painting, together with the volume it represents (… the painter’s salon …), and, in front of that surface, the real volume occupied by the spectator …” (445).

The window brightens the room within the painting, balances it against the dark void of that canvas of which we see only ever its back … lights all the painting’s representation and the concealed image … revealing to concealing.

“so that the flood of light streaming through it bathes at the same time, and with equal generosity, two neighboring spaces, overlapping but irreducible: the surface of the painting, together with the volume it represents (… the painter’s salon …), and, in front of that surface, the real volume occupied by the spectator …” (445).

The window brightens the room within the painting, balances it against the dark void of that canvas of which we see only ever its back … lights all the painting’s representation and the concealed image … revealing to concealing.

|

And opposite behind this lightened line across the painting’s forefront, there is a wall of paintings, with one standing out brighter: a picture that is not a picture, a mirror … illuminating two subjects … “fulfills its function in all honesty and enables us to see what it is supposed to show” (446): the subjects of the painter’s (hidden) painting … “Of all the representations represented in the picture this is the only one visible; but no one is looking at it” (446)—it is behind the backs of all the subjects in the painting, but shows us the subjects of the painting’s painting.

|

- Mirrors – their traditional role in paintings … “they play a duplicating role” (446):

- mise-en-abyme (‘placed in an abyss’ – abyme’s origin in heraldry, being the center of an escutcheon, a shield or coat of arms, a shield-like image that held a miniature reduplication of the whole) an artistic effect found in early medieval art wherein a picture appears within its own picture, which initiates a visual infinite regress to the very boundaries of its resolution; more commonly known today as the Droste effect (thanks to Droste cocoa advertising), although popularized as item of aesthetic theory by André Gide to describe self-reflexive embedding in art: “In a work of art I rather like to find transposed, on the scale of the characters, the very subject of that work. Thus in paintings by Memling or Quentin Metzys, a small dark convex mirror reflects the interior of the room in which the action of the painting takes place. Likewise in Velázquez’s painting of the Meniñas … in the play scene in Hamlet and in many other plays. None of these is altogether exact. … a comparison with the device from heraldry that involves putting a second representation of the original shield ‘en abyme’ within it” (From Gide’s journals, quoted in Stuart Whatling, “Putting Mise-en-abyme in its (medieval) place,” collected conference papers: Medieval ‘mise-en-abyme’: the object depicted within itself, 2/16/2009: web.archive.org/web/20131102033517/http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/researchforum/projects/medievalarttheory/documents/Mise-en-abyme.pdf).

Given that the mirror duplicates—and it is central in the painting: its upper edge is the half way line of the top and bottom, its position on the wall is dead center—it seems like it should show the whole of the painting’s room … but it shows nothing that the painting shows … it shows only what the painting doesn’t show.

§2 (pp.447-54):

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by MacHighway