The weeds appearing over the last year in my little Nashville yard have proved so, so many, a third page of their inventory is now required ...

|

PAGE ONE:

1) Plantain (Plantago major) 2) Creeping Charlie (Glechoma hederacea) 3) Smilax (Smilax rotundifolia or S. bona-nox) 4) Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana) 5) Porcelainberry (Ampelopsis brevipedunculata) 6) Bush / Amur Honeysuckle (Lonicera Maackii) 7) Privet (Ligustrum sinense) 8) Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) 9) Wintercreeper (Euonymous fortunei) 10) Ivy (Hedera helix) 11) Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana and Duchesnea indica) 12) Violets (Viola spp.) 13) Speedwell (Veronica officinalis or V. americana) 14) Dock (Rumex spp.) 15) Buttercups (Ranunculus acris) 16) Crown vetch (Securigera varia) 17) Spurge (Euphorbia humistrata or E. maculata) 18) Bedstraw / Cleavers (Galium aparine) 19) Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) 20) Virginia Threeseed Mercury (Acalypha virginica) 21) Pennsylvania Smartweed (Polygonum pensylvanicum) |

22) Pigweed (Amaranthus palmeri)

23) Virginia Buttonweed (Diodia virginiana) 24) Oxalis (Oxalis stricta) 25) Creeping Cucumber (Melothria pendula) 26) Whitestar / Small White Morning Glory (Ipomoea lacunose) 27) Bindweed (Convolvus arvensis) 28) Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans or T. rydbergii) 29) Fleabane (Erigeron annuus or E. strigosus) PAGE TWO: 30) Pilewort (Erechtites hieraciifolius) 31) Lamb’s Quarters (Chenoposium album) 32) Swamp Rose-Mallow and Rose of Sharon (Hibiscus moscheutos and H. syriacus) 33) Mystery Umbellifer: Wild Carrot (Daucus carota), Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca), or Field Hedge Parsley (Torilis arvensis) 34) Mystery Asteraceae: Black- and Brown-Eyed Susans (Rudbeckia hirta and R. triloba) 35) Mystery Giant: Giant Ragweed (Ambrosia trifida) 36) Sweet Annie (Artemisia annua) 37) Mulberry Weed (Fatoua villosa) 38) Red Mulberry Tree |

39) Hackberry Tree (Celtis occidentalis)

40) American Elm (Ulmus americana) 41) White and Southern Red Oaks (Quercus Alba and Quercus falcata) 42) Cross Vine (Bignonia capreolata) 43) Star of Bethlehem (Ornithogalum umbellatum) 44) Garlic Chives (Allium tuberosum) 45) Late-Flowering Thoroughwort (Eupatorium serotinum) 46) Figwort (Scrophularia marilandica) 47) Italian Arum (Arum italicum) 48) Cranesbill (Geranium, likely G. carolinianum or G. bicknellii) PAGE THREE: 49) Red Dead-Nettle (Lamium purpureum) 50) Chickweed (Stellaria media) 51) Crow Garlic (Allium vineale) 52) Little-leaf or Fig-leaf Buttercup (Ranunculus abortivus) 53) Smallflower Baby Blue Eyes (Nemophila aphylla) 54) Black Medic (Medicago lupulina) 55) Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) 56) Perilla (Perilla frutescens) 57) Oriental False Hawksbeard (Youngia japonica) |

49)

|

Henbit & Red/Purple Dead-Nettle (Lamium amplexicaule & L. purpureum):

What unpleasant common names you two have been saddled with: ‘henbit’ comes from observations of chickens liking to grave on you, and ‘red’ or ‘purple,’ the former more British, the latter more American, for the rather obvious denomination by color gracing your upper leaves; further, you both share the common nominal addendum ‘dead-nettle,’ for some visual similarity, despite your being in the Lamiaceae (mint) family, not Urticaceae (nettle), with the ‘dead’ signifying your non-stinging nature. You are both non-natives (hailing from Europe and Asia), seed-prolific winter (occasionally summer) annuals, prefer disturbed ground with Henbit preferring a touch more shade, Red/Purple a bit more sun, and decried as (gasp) galling weeds. (Alaska, Kentucky, West Virginia, Maryland, and New Hampshire list Henbit as invasive; Kentucky, Maryland, and New Hampshire are quite against Red/Purple.) Your flowers are very similar, too: petite, pink to purple, a top petal shaped like a hood, two lower ones like lips; like your kin, you both bear square stems and average about ten inches tall; your differentiating feature is mainly your leaves: both bear crowded heart-shaped and wrinkly-looking hairy leaves with wavy or toothy margins, but Henbit’s upper ones whorl about and clasp their stems and have slightly more scalloped margins, while Red/Purple’s are borne on short petioles, its upper ones deeply maroon-rouged and margins more spiked. Both of you are highly attractive to honey, bumble, and other long-tongued bees and the parasitic bee-mimic, Bombylius major, or the giant bee flyseeking nectar when most spring plants have yet to bloom, as well as attracting some hummingbirds. Both species are edible, with Henbit more often singled out for nibbling, but some sites offer both in weed teas and pestos; Henbit also bears gratitude for providing erosion control in the south.* * Cf., for Lamium amplexicaule: Illinois Wildflowers, available ~~HERE~~; North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, available ~~HERE~~; Wisconsin Horticulture, available ~~HERE~~; Ivasive.org, available ~~HERE~~; for Lamium purpureum: Illinois Wildflowers, available ~~HERE~~; North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, available ~~HERE~~; Plants for a Future, available ~~HERE~~; for both and other information, including edibility: Michigan State University, available ~~HERE~~; Grow, Forage, Cook, Ferment, available ~~HERE~~; Natural Living Ideas, available ~~HERE~~; Edible Wild Food, available ~~HERE~~. |

Red / Purple Dead-Nettles:

|

50)

Chickweed (Stellaria media):

With your extremely petite, shimmering quintet of bifid white petals like stars rising up from long stretching, slight fuzzy, somewhat rosy stems that bear little pointy-tipped oval leaves, I find you far more lovely than your demotion being “as synonymous with ‘lawn weed’ as the common dandelion.”* Sure, you are not native here—your origins are in Europe and Asia—and you are rather prolific, not minding nearly any light condition or soil type, especially disturbed grounds, reseeding rapidly and spreading as well vegetatively by the nodes along your sprawling stems. Although you can self-pollinate, your pollen and nectar do, however, attract a number of small bees and flies, occasionally butterflies and wasps, and various larvae and adult beetles and moths (being larval host for the Venerable Dart and the especially lovely pink-dotted, yellow winged Chickweed Geometer moths), not to mention rabbits, groundhogs, and deer, will munch your leaves, while they and your seeds are also enjoyed by a number of doves, sparrows, and grouse. Unfortunately, you also host spider mites and, perhaps, tomato spotted wilt and cucumber mosaic viruses.**

Chickweed, it should be noted, has a long medicinal and gustative history. David Allen and Gabrielle Hatfield, in their Medicinal Plants in Folk Tradition, rightfully point out that the “cosmopolitan weed” Stellaria media and its frequent neighbor Senecio vulgaris “perhaps because of their very commonness as weeds and therefore ready availability … are alike in having been employed for an impressive diversity of ailments.”*** The chief benefit of Chickweed, called Indian Chickweed and Starwort in the tall, narrow, and long 1930’s herbal and retail guide by Joseph E. Meyers—and almost musically describes as a common European and American plant “growing in fields and around dwellings, in moist, shady places. It flowers from the beginning of spring ‘til the last of autumn”—is as a “cooling demulcent,” something that relieves inflammation, when its fresh bruised leaves are applied as a poultice or mixed with lard for an ointment.† (The Healthline site’s linking of medical articles suggests support for the old herbals.††) There is an even more fantastic description in The Old English Herbarium that reads: “This plant shines at night like the stars in the skies, and those who see it without knowing that, say they have seen an apparition, and, this frightened, they are ridiculed by shepherds and those who know more about the power of the plant”—however, there is long scholarly debate as to whether it applies to asters or chickweed, with a certain Grieve arguing for it to be the latter for its “flowers open about nine a.m. and are said to remain open for twelve hours, thus, into the night.”†††

Chickweed, having, according to Gail Harland’s Edible Weeds, a “mild grassy taste … more acceptable to children than many other wild greens,” and especially good when used like cress in egg sandwiches or in recipes calling for spinach, is rich in magnesium for all its tasters, but was specifically named for its gastronomical favor by birds and reportedly sold in Victorian London for a half penny per bunch for feeding caged songbirds.◊ Kenneth Thompson’s The Book of Weeds: How to Deal with Plants that Behave Badly, grudgingly confirms that chickweed—dully described as a “rather limp, pale-green annual”—“has a long history as food for chickens and caged birds,” and is edible for humans, too, “but it’s difficult to collect enough, or to gather leaves without a mud garnish,” hence recommends “Hoeing is effective,” although “It’s easy and rather satisfying to pull up handfuls.”◊◊

With your extremely petite, shimmering quintet of bifid white petals like stars rising up from long stretching, slight fuzzy, somewhat rosy stems that bear little pointy-tipped oval leaves, I find you far more lovely than your demotion being “as synonymous with ‘lawn weed’ as the common dandelion.”* Sure, you are not native here—your origins are in Europe and Asia—and you are rather prolific, not minding nearly any light condition or soil type, especially disturbed grounds, reseeding rapidly and spreading as well vegetatively by the nodes along your sprawling stems. Although you can self-pollinate, your pollen and nectar do, however, attract a number of small bees and flies, occasionally butterflies and wasps, and various larvae and adult beetles and moths (being larval host for the Venerable Dart and the especially lovely pink-dotted, yellow winged Chickweed Geometer moths), not to mention rabbits, groundhogs, and deer, will munch your leaves, while they and your seeds are also enjoyed by a number of doves, sparrows, and grouse. Unfortunately, you also host spider mites and, perhaps, tomato spotted wilt and cucumber mosaic viruses.**

Chickweed, it should be noted, has a long medicinal and gustative history. David Allen and Gabrielle Hatfield, in their Medicinal Plants in Folk Tradition, rightfully point out that the “cosmopolitan weed” Stellaria media and its frequent neighbor Senecio vulgaris “perhaps because of their very commonness as weeds and therefore ready availability … are alike in having been employed for an impressive diversity of ailments.”*** The chief benefit of Chickweed, called Indian Chickweed and Starwort in the tall, narrow, and long 1930’s herbal and retail guide by Joseph E. Meyers—and almost musically describes as a common European and American plant “growing in fields and around dwellings, in moist, shady places. It flowers from the beginning of spring ‘til the last of autumn”—is as a “cooling demulcent,” something that relieves inflammation, when its fresh bruised leaves are applied as a poultice or mixed with lard for an ointment.† (The Healthline site’s linking of medical articles suggests support for the old herbals.††) There is an even more fantastic description in The Old English Herbarium that reads: “This plant shines at night like the stars in the skies, and those who see it without knowing that, say they have seen an apparition, and, this frightened, they are ridiculed by shepherds and those who know more about the power of the plant”—however, there is long scholarly debate as to whether it applies to asters or chickweed, with a certain Grieve arguing for it to be the latter for its “flowers open about nine a.m. and are said to remain open for twelve hours, thus, into the night.”†††

Chickweed, having, according to Gail Harland’s Edible Weeds, a “mild grassy taste … more acceptable to children than many other wild greens,” and especially good when used like cress in egg sandwiches or in recipes calling for spinach, is rich in magnesium for all its tasters, but was specifically named for its gastronomical favor by birds and reportedly sold in Victorian London for a half penny per bunch for feeding caged songbirds.◊ Kenneth Thompson’s The Book of Weeds: How to Deal with Plants that Behave Badly, grudgingly confirms that chickweed—dully described as a “rather limp, pale-green annual”—“has a long history as food for chickens and caged birds,” and is edible for humans, too, “but it’s difficult to collect enough, or to gather leaves without a mud garnish,” hence recommends “Hoeing is effective,” although “It’s easy and rather satisfying to pull up handfuls.”◊◊

* Minnesota Wildflowers, available ~~HERE~~.

** Illinois Wildflowers, available ~~HERE~~, and Clemson Cooperative Extension, available ~~HERE~~.

*** David E. Allen and Gabrielle Hatfield, Medicinal Plants in Folk Tradition: An Ethnobotany of Britain and Ireland (Portland: Timber Press, 2004), 91-92.

† Joseph E. Meyer, The Herbalist (Hammond, IN: Hammond Book Company, 1934), 133.

†† “Chickweed: Benefits, Side Effects, Precautions, and Dosage,” Healthline, available ~~HERE~~.

††† Anne Van Arsdall, Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine, chapter five: “A New Translation of the Old English Herbarium” (New York: Routledge, 2002), 176, and n.181.

◊ Gail Harland, Edible Weeds, 76.

◊◊ Kenneth Thompson, The Book of Weeds: How to Deal with Plants that Behave Badly (DK Publishing, 2009), 98.

** Illinois Wildflowers, available ~~HERE~~, and Clemson Cooperative Extension, available ~~HERE~~.

*** David E. Allen and Gabrielle Hatfield, Medicinal Plants in Folk Tradition: An Ethnobotany of Britain and Ireland (Portland: Timber Press, 2004), 91-92.

† Joseph E. Meyer, The Herbalist (Hammond, IN: Hammond Book Company, 1934), 133.

†† “Chickweed: Benefits, Side Effects, Precautions, and Dosage,” Healthline, available ~~HERE~~.

††† Anne Van Arsdall, Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine, chapter five: “A New Translation of the Old English Herbarium” (New York: Routledge, 2002), 176, and n.181.

◊ Gail Harland, Edible Weeds, 76.

◊◊ Kenneth Thompson, The Book of Weeds: How to Deal with Plants that Behave Badly (DK Publishing, 2009), 98.

51)

|

Crow Garlic (Allium vineale):

In the earliest days of spring—winter, really, wishfully thinking—I decided to commit to crafting (cease overly-deliberating on) a wildflower and weed zone out of a semi-circle of “lawn” around my berry pots. I trenched a 30-foot arced edge, built a rickety fig branch knee-high fence, and grumbled about the tufts of grass all over (the “lawn” was seeded with only clover, which never took, so all its growth has been fully volunteer)—then looked closer … some of those clumps were especially peculiar, graced with a more blueish hue, tall and thread-like … some sort of Allium! Crow Garlic, Field Garlic, Wild Garlic, Stag’s Garlic, False Garlic, Onion Grass, Wild Onion, or Compact Onion—your common names are many, and you are a common discovery in sunny lawns and disturbed places (perhaps in vineyards, too, as suggested by your species name), from your native lands through Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and western Asia, and colonial-era introduced to and now naturalized across much of the eastern and southern U.S. (the eastern side of Canada, too, |

as well as the U.S.’s west coast states). You appear, from small bulbs, in the earliest of spring looking so very much like clumps of grass (several inches to nearly three feet tall) until close inspection—revealing your leaves are thin, hollow, chive-like tubes, and smell pronouncedly of garlic when crushed, proving you no grass or sedge, but a member of the Amaryllidaceae (lily) family—and go dormant after the early summer, sometimes returning in the early fall. Spreading by seeds, aerial bulbils, and offsets from your bulbs, you are an aggressive spreader, quite repugnant to browsing deer (and if grazed by cows, their milk may taste horrid), quite recalcitrant to hand pulling (as the bulbs may be quite deep and bulblets will break off easily and quickly re-flourish), and quite resistant to pre-emergent herbicides.

Perhaps your best control are hungry humans, as you are a bit tough and excessively garlicky, but thoroughly edible, despite containing sulfides that may undo some, and usable like chives or garlic. Your leaves are accused of being a bit stringy (hence the keen tip from one forager to use them as a bouquet garni removed from a broth before serving), but, raw or cooked, serve as a fine garlic-substitute, or tossed lightly in a salad, as does your bulb or little bulbils. Eating the bulbs raw has been said to aid high blood pressure and ease shortness of breath, and a tincture of them is used for preventing worms and colic in kids, as well as remedying croup, and an overall tonic for the digestive and circulatory systems. Spilling a little bulb juice or strewing a few whole plants is also effective at ridding places of moths, or, slathered upon the skin, repelling biting insects. While wool-eating moths and biting flying bugs may dislike you, your nectar does attract some small bees and flower-attracted flies.

While you are aggressive to broaching invasive, your edibility does speak in your favor, along with your simply unusual aesthetics: describing your flower is a challenge. Arising tall from a naked central stalk, your flower, often, is not so much a typical Allium-umbel, but an explosion of green to red bulbils, or, a flower becoming such a hairy top of bulbils, or, a shag-top topped with a few flowers, or, when not bulbil-full, more typical Allium flowers that are quite showy, two to three inches wide, and varying in color from white to green to purples ranging from lavender to muddy wine. (The descriptions and photographs of your floral variety has ensured my saving you from the compost pile—for now, at least—for these I have got to see, so, photos of blooms hopefully forthcoming.)*

* Cf., North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, available ~~HERE~~; Native Plant Trust, Go Botany, available ~~HERE~~; Plants for a Future, available ~~HERE~~; Backyard Forager, available ~~HERE~~; Purdue University Landscape Report, available ~~HERE~~; Illinois Wildflowers, available ~~HERE~~; Invasive Plant Atlas, available ~~HERE~~; Missouri Plants, available ~~HERE~~.

Perhaps your best control are hungry humans, as you are a bit tough and excessively garlicky, but thoroughly edible, despite containing sulfides that may undo some, and usable like chives or garlic. Your leaves are accused of being a bit stringy (hence the keen tip from one forager to use them as a bouquet garni removed from a broth before serving), but, raw or cooked, serve as a fine garlic-substitute, or tossed lightly in a salad, as does your bulb or little bulbils. Eating the bulbs raw has been said to aid high blood pressure and ease shortness of breath, and a tincture of them is used for preventing worms and colic in kids, as well as remedying croup, and an overall tonic for the digestive and circulatory systems. Spilling a little bulb juice or strewing a few whole plants is also effective at ridding places of moths, or, slathered upon the skin, repelling biting insects. While wool-eating moths and biting flying bugs may dislike you, your nectar does attract some small bees and flower-attracted flies.

While you are aggressive to broaching invasive, your edibility does speak in your favor, along with your simply unusual aesthetics: describing your flower is a challenge. Arising tall from a naked central stalk, your flower, often, is not so much a typical Allium-umbel, but an explosion of green to red bulbils, or, a flower becoming such a hairy top of bulbils, or, a shag-top topped with a few flowers, or, when not bulbil-full, more typical Allium flowers that are quite showy, two to three inches wide, and varying in color from white to green to purples ranging from lavender to muddy wine. (The descriptions and photographs of your floral variety has ensured my saving you from the compost pile—for now, at least—for these I have got to see, so, photos of blooms hopefully forthcoming.)*

* Cf., North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, available ~~HERE~~; Native Plant Trust, Go Botany, available ~~HERE~~; Plants for a Future, available ~~HERE~~; Backyard Forager, available ~~HERE~~; Purdue University Landscape Report, available ~~HERE~~; Illinois Wildflowers, available ~~HERE~~; Invasive Plant Atlas, available ~~HERE~~; Missouri Plants, available ~~HERE~~.

52)

Little-leaf or Fig-leaf Buttercup (Ranunculus abortivus):

All the other buttercups—a brief mystery buttercup, creeping buttercup, and early buttercup—are featured on The Weed Inventory’s first page, at listing 15 … but it ran long, and was well added to already before my back yard erupted with five spectacular new-to-here buttercups—so!, a new listing: hello Little-Leaf Buttercup (R. abortivus)!

All the other buttercups—a brief mystery buttercup, creeping buttercup, and early buttercup—are featured on The Weed Inventory’s first page, at listing 15 … but it ran long, and was well added to already before my back yard erupted with five spectacular new-to-here buttercups—so!, a new listing: hello Little-Leaf Buttercup (R. abortivus)!

|

Admittedly, I was utterly uncertain that you were buttercups … what unusual specimens you are, most distinct from your brethren. You are a North American native, partial to richly and moistly-soiled woods or shadier and disturbed areas, and go by several common names: little-leaf, kidney-leaf, or early wood buttercup, or small-flower crowfoot. (Your species name from the Latin for aborted, suggesting your ‘missing’ flashy petals.) As your names suggest, your flowers are especially small, as are your unusual leaves. Your one to several quarter-inch petite flowers are a bit bulbous, bobbling at the ends of naked, branching stems, but do bear the normal five petals, albeit paler than most, and ring of brighter yellow stamens looping around a bludging bright yellow-green center. It was the Ides of March when you were in full bloom here, although you reportedly tend to bloom for a month or two mid-spring through the early summer. Your low basal leaves are large (nearly two inches long a bit wider) and range from round to tri-lobing kidney-shaped with daintily scalloped edges—although the first to show could easily be mistaken for a young violet or creeping charlie—while your upper alternatively-attached leaves are mostly long and skinny (perhaps an occasional long, skinny lobe cut), mostly smooth margins, and hardly stalked to your green, smooth stems. Here, your height has varied from barely six inches to the tallest at maybe fourteen, although you can reportedly grow up to a good two feet. Your nectar, and sometimes pollen, is attractive to ladybird beetles and small bees and flies, while the wood duck, turkeys, and cottontail rabbits are said to not mind a munch of

|

your leaves, and the chipmunks and voles may eat your seeds. Like all your family members, your foliage is irritating and unpalatable to mildly toxic to grazing animals.* While most sites call you rather weedy, and all note how easy it is to overlook your sparse, small flowers, I find you to be quite an attractive new comer with your unusual variation on the classic buttercup flower and unique two-style leaves—it also did not hurt when you jumped into the fig bed, coming up to bloom your little bulging hearts out surrounded by a mass of dark purple violets.

* Cf., Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, available ~~HERE~~; Minnesota Wildflowers, available ~~HERE~~; Illinois Wildflowers, available ~~HERE~~; Native Plant Trust Go Botany, available ~~HERE~~; Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden, available ~~HERE~~.

53)

Smallflower Baby Blue Eyes (Nemophila aphylla):

Native and endemic to the southeastern U.S., you have lovely names, though so little is written about you—despite your range seeming just as large as the more chronicled Baby Blue Eyes, the “most charming” wildflower of the West Coast. Your genus name was granted in 1822 by Thomas Nuttall from the conjunction of the Greek nemos, a glade, and phileo, to love, hence naming your “affinity for groves.” The ‘smallflower’ of your common name is an understatement—miniscule is more like it, perhaps three millimeters maximum from side to side, top to bottom of your five petals surrounding a pin-prick sized center, but described by one gardening site as nevertheless “showy.” The ‘baby blue’ part could be slightly misleading if not qualified as basically white with maybe, maybe a slightest staining of a pale, pale hint of cloudy blue. Your bright spring-green leaves are wonderfully wildly shaped in clusters of three to five irregularly lobed parts coming to globular, almost points, and dramatically covered in notable white hairs. Overall petite, your heights range from two to six inches, and spread of six to eight with rather weak stems. A springtime annual, you are fond of moist soils, and are, thus reasonably so, tolerant of high humidity, often appearing in woodlands—except, for me, you seem to prefer the cracks in the south-facing garden flagstone path and a few spots in the more back, shadier hydrangea bed. I have witnessed no one paying you any mind, but you are reportedly eaten by the owlet moth named Oligia marina.*

You belong to the Hydrophyllaceae, Waterleaf, family (summed up by one site as “small, hairy plants with parts in fives, united,” with long-stamened flowers whose stalks that ten to curl over, “like a scorpion tail,” named for the pale leaf mottling suggestive of watermarks on paper, and inclusive of about 20 genera, 16 of which are North American natives, notably the tall Virginia Waterleaf (Hydrophyllum virginianum)), which is actually a subfamily of the Boraginaceae, Borage or Forget-Me-Not, family (also noted as “hairy plants with flower parts in fives,” except its fruits forming four nutlets, and comprised of over 100 genera, mostly astringent medicinal plants like Borage (Borago officinalis) and Comfrey (Symphytum officinale), as well as Heliotrope (Heliotropium), Virginia Bluebell (Mertensia virginica), and Lungwort (Pulmonaria)).**

* Cf., Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, available ~~HERE~~; Wildflower Search, available ~~HERE~~; Encyclopedia of Life, available ~~HERE~~; The National Gardening Association Plants Database, available ~HERE~~; 2bnTheWild’s Wildflowers of the Southeastern U.S., available ~HERE~~.

** Cf., Wildflowers and Weeds, available ~~HERE~~ and ~~HERE~~; Britannica, available ~~HERE~~ and ~~HERE~~.

Native and endemic to the southeastern U.S., you have lovely names, though so little is written about you—despite your range seeming just as large as the more chronicled Baby Blue Eyes, the “most charming” wildflower of the West Coast. Your genus name was granted in 1822 by Thomas Nuttall from the conjunction of the Greek nemos, a glade, and phileo, to love, hence naming your “affinity for groves.” The ‘smallflower’ of your common name is an understatement—miniscule is more like it, perhaps three millimeters maximum from side to side, top to bottom of your five petals surrounding a pin-prick sized center, but described by one gardening site as nevertheless “showy.” The ‘baby blue’ part could be slightly misleading if not qualified as basically white with maybe, maybe a slightest staining of a pale, pale hint of cloudy blue. Your bright spring-green leaves are wonderfully wildly shaped in clusters of three to five irregularly lobed parts coming to globular, almost points, and dramatically covered in notable white hairs. Overall petite, your heights range from two to six inches, and spread of six to eight with rather weak stems. A springtime annual, you are fond of moist soils, and are, thus reasonably so, tolerant of high humidity, often appearing in woodlands—except, for me, you seem to prefer the cracks in the south-facing garden flagstone path and a few spots in the more back, shadier hydrangea bed. I have witnessed no one paying you any mind, but you are reportedly eaten by the owlet moth named Oligia marina.*

You belong to the Hydrophyllaceae, Waterleaf, family (summed up by one site as “small, hairy plants with parts in fives, united,” with long-stamened flowers whose stalks that ten to curl over, “like a scorpion tail,” named for the pale leaf mottling suggestive of watermarks on paper, and inclusive of about 20 genera, 16 of which are North American natives, notably the tall Virginia Waterleaf (Hydrophyllum virginianum)), which is actually a subfamily of the Boraginaceae, Borage or Forget-Me-Not, family (also noted as “hairy plants with flower parts in fives,” except its fruits forming four nutlets, and comprised of over 100 genera, mostly astringent medicinal plants like Borage (Borago officinalis) and Comfrey (Symphytum officinale), as well as Heliotrope (Heliotropium), Virginia Bluebell (Mertensia virginica), and Lungwort (Pulmonaria)).**

* Cf., Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, available ~~HERE~~; Wildflower Search, available ~~HERE~~; Encyclopedia of Life, available ~~HERE~~; The National Gardening Association Plants Database, available ~HERE~~; 2bnTheWild’s Wildflowers of the Southeastern U.S., available ~HERE~~.

** Cf., Wildflowers and Weeds, available ~~HERE~~ and ~~HERE~~; Britannica, available ~~HERE~~ and ~~HERE~~.

54)

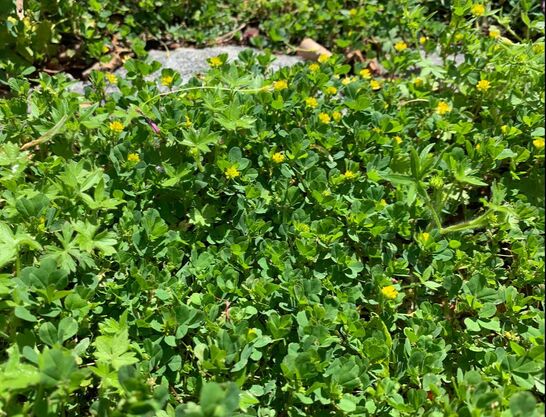

Black Medic (Medicago lupulina)

From your Eurasian native lands to the United States—imported for agricultural uses, be it for hungry livestock or field repair, in the early 1800’s—you are a clover-leafed-looking little winter or summer annual in the Fabaceae (bean) family, and have garnered a number of foes. Besides ‘Black Medic,’ you have been known to go by names like: Yellow Trefoil, Black Nonesuch, Blackweed, Black Clover, Hop Clover, and Japanese Clover. Your stems are both and between prostrate (capable of reaching a foot or two in length) and ascending, light green to reddish green, the young ones fuzzy with white hairs, and an occasional branch from your base; these support alternate, deeply green trifoliate leaves—petite, but, again, looking quite like baby clover—with very fine lateral, light green veins, and the slightest of fine dentate cutting around the edges. Your typically April to July and some places over and over February to December flowers complete the fine picture: slightly elongated-globe-shaped heads formed by dense clusters of barely three millimeter long pale to nearly buttercup-yellow flowers. When they are fully open, a very, very close inspection can reveal their pea-shape with an upper standard and lower keel structure; the base of each a pale green, five-toothed calyx. When they fade, they are replaced with numerous black seed pods, dark, hairy, curled, and containing just a single amber-colored kidney-shaped seed (each plant capable of producing more than 1,000 seeds, with one source claiming 6,600 and with a soil viability rate of several years). Under ground, your roots are a fairly shallow tap with branches, and can form nodules; like your bean kin, they are nitrogen-fixing. Despite your overall delicate appearance, you are an aggressive little one, capable of forming large colonies across zones 3a to 9b, and are pretty flexible as to soil

From your Eurasian native lands to the United States—imported for agricultural uses, be it for hungry livestock or field repair, in the early 1800’s—you are a clover-leafed-looking little winter or summer annual in the Fabaceae (bean) family, and have garnered a number of foes. Besides ‘Black Medic,’ you have been known to go by names like: Yellow Trefoil, Black Nonesuch, Blackweed, Black Clover, Hop Clover, and Japanese Clover. Your stems are both and between prostrate (capable of reaching a foot or two in length) and ascending, light green to reddish green, the young ones fuzzy with white hairs, and an occasional branch from your base; these support alternate, deeply green trifoliate leaves—petite, but, again, looking quite like baby clover—with very fine lateral, light green veins, and the slightest of fine dentate cutting around the edges. Your typically April to July and some places over and over February to December flowers complete the fine picture: slightly elongated-globe-shaped heads formed by dense clusters of barely three millimeter long pale to nearly buttercup-yellow flowers. When they are fully open, a very, very close inspection can reveal their pea-shape with an upper standard and lower keel structure; the base of each a pale green, five-toothed calyx. When they fade, they are replaced with numerous black seed pods, dark, hairy, curled, and containing just a single amber-colored kidney-shaped seed (each plant capable of producing more than 1,000 seeds, with one source claiming 6,600 and with a soil viability rate of several years). Under ground, your roots are a fairly shallow tap with branches, and can form nodules; like your bean kin, they are nitrogen-fixing. Despite your overall delicate appearance, you are an aggressive little one, capable of forming large colonies across zones 3a to 9b, and are pretty flexible as to soil

conditions, wet to dry, loam to clay to gravel, and partially to fully sunny, but also amenable to shade cast by tall prairie plants or food crops. Your aggressiveness, and propensity to muscle through lawns, hop into field crops, as well as crowd out beneficial native species in wild areas, have won you many enemies, with numerous extension services advising on your removal—hand-pulling pre-seeding is advised, or dousing you with broad-leaf weed killer, or letting animals munch you away, although too much of you can cause bloating in cattle, they say. However, there are a few reasons your weediness may be welcomed (or, at least, not so reviled.) Besides your nitrogen-fixing powers, hence making a fine green manure crop, mammal critters quite enjoy munching you, and your flowers’ nectar and pollen attract flies and small butterflies, and numerous bees. In the medicine cabinet, you reportedly have antibacterial properties and have served useful as a mild laxative and to increase blood clotting. In the kitchen, you are indeed an edible, with European and Asian accounts of your high-protein leaves cooked like spinach (raw, you are reportedly a bit overly bitter, and some wonder if your close relation to alfalfa could indicate you, too, have a dangerous level, when uncooked, of L-canavanine amino acid that can harm blood counts), and Depression-era Native Americans roasting your seeds and grinding them into flour.*

* Cf., Illinois Wildflowers, available ~~HERE~~; North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, available ~~HERE~~; Gardening Know How, available ~~HERE~~; U.S. Federal Invasive Plants and Weeds of the National Forests and Grasslands in the SW Region, available ~~HERE~~; Washington State University Extension, available ~~HERE~~; University of California Agricultural and Natural Resources, available ~~HERE~~; Eat the Weeds, available ~~HERE~~.

* Cf., Illinois Wildflowers, available ~~HERE~~; North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, available ~~HERE~~; Gardening Know How, available ~~HERE~~; U.S. Federal Invasive Plants and Weeds of the National Forests and Grasslands in the SW Region, available ~~HERE~~; Washington State University Extension, available ~~HERE~~; University of California Agricultural and Natural Resources, available ~~HERE~~; Eat the Weeds, available ~~HERE~~.

55)

Black Cherry (Prunus serotina):

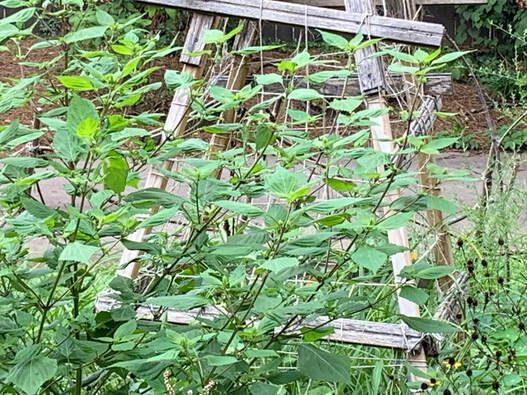

Another tree to whom I must apologize for the “weed” designation—but, you have been rather widely called a weedy invader, and five of you did appear in my hydrangea bed quite uninvited. You appeared last summer, but as such small and scrappy seedlings, you were quite challenging to identify. I had a hunch, but needed to wait for you to acquire a little more size, hence, this spring, finally, with over a half a dozen leaves on your largest of newcomers, I think my hunch is accurate: hello Wild Black Cherry!, what am I going to do with you? Had I ample acres, I’d have a rich and wildly diverse, dense, moody woodland; had I even just a touch more room for tree planting here than I do, I would be planting Dwarf Chinkapin Oak (Quercus prinoides), but, admittedly, Wild Black Cherry (Prunus serotina), you were very near the top of my list well before you five arrived (perhaps not second, as you average 60-80 feet tall and wide, but close to, surely), mainly sealed in the high slot by your being a host to so many butterflies and productive of much loved songbird fruit. While your size (especially given your saplings’ chosen positions) was warning me off like air raid sirens coming through headphones, I was warmed up to you by Douglas Tallamy’s repeated mentions of you through his Bringing Nature Home—granted, the first two were a touch unsettling to my hyper plant empathy: a photo of your thoroughly eaten leaves and mention of your complete defoliation by tent caterpillars, no matter that his point was to champion how amenable you are to supporting native insects; this positive point was repeatedly enforced with numeric data (common natives like you producing four times more biomass for herb-munchers than alien species and thus supporting three point two times more of those herbivores) and keen illustrative examples (narratively and by stunning photographs showing that you and your genus are the third most ranking supporters of Lepidoptera—including the Red-Spotted Purple (Limenitis arthemis), a delightful glimmering aqua-lapis beauty with orange spots I’ve frequently spotted flittering about the yard—as well as supporting numerous birds with your fruits).* The Audubon Society’s Native Plant database further promotes you for attracting all of my favorite feathery visitors: wrens, wood warblers, nuthatches, woodpeckers, mockingbirds, thrashers, cardinals, grosbeaks, crows, jays orioles, vireos, waxwings, chickadees, titmice, sparrows, and thrushes.**

So, who are you?: a native tree (predominately the eastern half of the U.S., but also varieties specific to the southwest) beloved by birds and butterflies, carpenters—the human sort, for your wood is lovely, richly toned and finely grained, gorgeous in all things from furniture to musical instruments—and homemakers—as your bitter cherries make fine jams and wine and uniquely flavored rum in Appalachian pioneer days, and your bark has been used by Native Americans and settlers alike for a tonic, cough syrup, and sedative … even while you are quite disliked for being terribly poisonous—everything but your cherry fruits are dangerous, especially wilted leaves and twigs and seeds, keen carriers of cyanide—or just messy, aggressively weedy, and rife with disease and insect problems. You also earn the rare distinction of being one of the few New World species turned invasive in the Old World, for as early as 1629 you were imported into English gardens due your fine looks—gorgeous drooping white flowers, fine and shiny red-to-black fruits, brilliant autumnal gold, and attractive bark—and are now deemed highly invasive there (too, in northern South America, have you taken over).

Another tree to whom I must apologize for the “weed” designation—but, you have been rather widely called a weedy invader, and five of you did appear in my hydrangea bed quite uninvited. You appeared last summer, but as such small and scrappy seedlings, you were quite challenging to identify. I had a hunch, but needed to wait for you to acquire a little more size, hence, this spring, finally, with over a half a dozen leaves on your largest of newcomers, I think my hunch is accurate: hello Wild Black Cherry!, what am I going to do with you? Had I ample acres, I’d have a rich and wildly diverse, dense, moody woodland; had I even just a touch more room for tree planting here than I do, I would be planting Dwarf Chinkapin Oak (Quercus prinoides), but, admittedly, Wild Black Cherry (Prunus serotina), you were very near the top of my list well before you five arrived (perhaps not second, as you average 60-80 feet tall and wide, but close to, surely), mainly sealed in the high slot by your being a host to so many butterflies and productive of much loved songbird fruit. While your size (especially given your saplings’ chosen positions) was warning me off like air raid sirens coming through headphones, I was warmed up to you by Douglas Tallamy’s repeated mentions of you through his Bringing Nature Home—granted, the first two were a touch unsettling to my hyper plant empathy: a photo of your thoroughly eaten leaves and mention of your complete defoliation by tent caterpillars, no matter that his point was to champion how amenable you are to supporting native insects; this positive point was repeatedly enforced with numeric data (common natives like you producing four times more biomass for herb-munchers than alien species and thus supporting three point two times more of those herbivores) and keen illustrative examples (narratively and by stunning photographs showing that you and your genus are the third most ranking supporters of Lepidoptera—including the Red-Spotted Purple (Limenitis arthemis), a delightful glimmering aqua-lapis beauty with orange spots I’ve frequently spotted flittering about the yard—as well as supporting numerous birds with your fruits).* The Audubon Society’s Native Plant database further promotes you for attracting all of my favorite feathery visitors: wrens, wood warblers, nuthatches, woodpeckers, mockingbirds, thrashers, cardinals, grosbeaks, crows, jays orioles, vireos, waxwings, chickadees, titmice, sparrows, and thrushes.**

So, who are you?: a native tree (predominately the eastern half of the U.S., but also varieties specific to the southwest) beloved by birds and butterflies, carpenters—the human sort, for your wood is lovely, richly toned and finely grained, gorgeous in all things from furniture to musical instruments—and homemakers—as your bitter cherries make fine jams and wine and uniquely flavored rum in Appalachian pioneer days, and your bark has been used by Native Americans and settlers alike for a tonic, cough syrup, and sedative … even while you are quite disliked for being terribly poisonous—everything but your cherry fruits are dangerous, especially wilted leaves and twigs and seeds, keen carriers of cyanide—or just messy, aggressively weedy, and rife with disease and insect problems. You also earn the rare distinction of being one of the few New World species turned invasive in the Old World, for as early as 1629 you were imported into English gardens due your fine looks—gorgeous drooping white flowers, fine and shiny red-to-black fruits, brilliant autumnal gold, and attractive bark—and are now deemed highly invasive there (too, in northern South America, have you taken over).

Nearly everyone on the long list of birds keen on your fruits are frequent feathery friends found in my yard and, according to the Department of Agriculture’s thorough report on you, songbirds are responsible for a modest amount of your seed distribution, thus nearly any of the avian cherry-eaters could have been responsible for your arrival in my hydrangea bed. The question remains: what do I do with you? Cyanide aside, your benefits are many and aesthetics fine. Your chosen sites are crowded, however, and mostly shaded by the neighbor’s line of old, tall hackberries, and while you are keen to germinate in shady, moist soils, this is not ideal situation for your permanent growth. Granted, this may be your salvation here: according to the Department of Agriculture, cherry seedlings under a dense canopy may be short-lived and grow just a half a foot, so perhaps with the hydrangea bed’s morning sun you can grow, but just not terribly tall. Otherwise, I am also heartened by the suggestion, in the North Carolina Extension Gardener’s Plant Toolbox page, that cutting you to the ground every two to three years can keep you at shrub size. For now, then, Black Cherry, you can stay.***

* Douglas W. Tallamy, Bringing Nature Home: How You Can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2007), 14-15, 52, 59, 156-61.

** Audubon Native Plants Database, available ~~HERE~~.

*** Cf., U.S. Department of Agriculture, Southern Research Station publication, available ~~HERE~~; U.S. Department of Agriculture Fire Effects Information System Species Information, available ~~HERE~~; Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, available ~~HERE~~; Illinois Wildflowers, available ~~HERE~~; North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, available ~~HERE~~; Native Plant Trust Go Botany, available ~~HERE~~; Florida Native Plant Society, available ~~HERE~~.

* Douglas W. Tallamy, Bringing Nature Home: How You Can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2007), 14-15, 52, 59, 156-61.

** Audubon Native Plants Database, available ~~HERE~~.

*** Cf., U.S. Department of Agriculture, Southern Research Station publication, available ~~HERE~~; U.S. Department of Agriculture Fire Effects Information System Species Information, available ~~HERE~~; Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, available ~~HERE~~; Illinois Wildflowers, available ~~HERE~~; North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, available ~~HERE~~; Native Plant Trust Go Botany, available ~~HERE~~; Florida Native Plant Society, available ~~HERE~~.

56)

|

Perilla (Perilla frutescens): Sometimes called the beefsteak plant (as some specimens, especially when purchased as seedling or specialty seed, are thoroughly ruby or raw steak colored), more often just perilla, this square-stemmed (hence Lamiaceae, mint, family member) is not unattractive, and human but not grazing cows or horses edible—but it is a non-native (Himalayan and Southeast Asian origins) and quite invasive (found across the eastern half of the U.S., invasive in many mid-Atlantic and mid-South states) volunteer. Several appeared in scrawny form under my birdfeeders, in my Hydrangea bed, and, in a grand and lovely towering form, my weed and wildflower bed. While hardy in zones 10-11, most places finds the perilla as a speedy-growing annual that can reach up to four feet, but more often half that height. Tolerant of mediocre soils, heat, and drought, they suffer almost no insect or disease issues, are avoided by most foraging wildlife, and reseed heartily. The stems are ruby streaked and hairy squares, the leaves have a tinge of purple beneath, solid, basic lush green above with their central vein carrying this hint of red from tip to end. Growing opposite, the largest leaves reach up to six, more often around four inches long and three wide, ovals ending in a point, margins serrated. Small, pale cream to sometimes pink flowers cluster on racemes at the branch ends and in axials at the main stem in late summer, attracting bees.

Widely used in Asian medicines—for its rich phytochemicals and showing (in some studies mostly on lab animals) effects against cancers of the colon and asthma (for its trachea soothing flavone luteolin), discouraging inflammation and microbial activity (namely blautia, which can cause glucose disturbance, and thereby aiding Lactobacillus growth, to aid the conversion of sugars to lactic acid, which may be helpful for diabetics), providing antioxidants (potentially higher than popular chia and flax seeds) and aiding the heart—and kitchens—Vitamin A, C, and riboflavin rich leaves are used as wraps, stuffed, pan fried, deep fried, sauteed, or pickled; the seeds, replete with fiber, calcium, magnesium, phosphorous, iron, niacin, protein, and thiamine, are used as seasoning or pressed for oil. (A close relation, the Perilla frutescens var. crispa, commonly known as shiso, is more well-known for its important use in Japanese cuisine.) Despite the potential medical and gustative virtues, the frequency of perilla’s appearance in my yard and the immense stature and lushness, and numerous buds thus soon seeds, on the example in my weed bed encourages me to send this one to the compost pile.* |

* North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, available ~~HERE~~; Missouri Botanical Garden, available ~~HERE~~; Native Plant Trust Go Botany, available ~~HERE~~; Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal article, available ~~HERE~~; Invasives.org page, available ~~HERE~~.

57)

Oriental False Hawksbeard (Youngia japonica): From a rosette of leaves (both sowthistle and dandelion-like, but hairy, and with a milky sap), your roughly foot-tall branching flowerstalk trumpets out small (barely a half-inch wide) copper budded, yellow daisy-shaped flowers (apt, as you are a member of the Asteraceae family) that fade out to mini-dandelion-esque white poofs of flyable seeds (similarly, again, your young leaves are edible raw or cooked). Here in Nashville, you are likely to flower just in late spring or early summer, but further south you may bloom all year. While attractive (to the Burnsius (checkered skipper) butterflies and this human’s eyes), you are ever more troublesomely invasive. (East Asia, and possibly Australia, is your homeland; you have been introduced throughout Africa, the Americas (as early as 1864 in Hawaii and 1933 in southeastern states), the Canary, Caribbean, and Pacific Islands.) While an annual or biennial, your seeds are many and equipped to fly far and wide, and boast an impressively high seed-set rate (80%) in controlled experiments. You are a fan of disturbed soils and the abandoned ones, wastelands, roadsides, cultivated fields and lawns, as well as natural, undisturbed areas, and will grow in nearly any soil, from clay to sand, acid to alkaline, from zone 5a to 10b, you prefer more moist and shadier sites, those well-dappled or with just partial

sun.* So, sadly—for you have a neat alt-dandelion look—you must go; not only are you already noted as invasive and potentially invasive, you have all the features—being so abundant in your wide native range, where you have also shown herbicide resistance; being so very adaptable to all cultural conditions; speedy to come, grow, and reproduce, hoisting your long-viable, prolific seeds aloft or afloat with highly effective flying fluff; and (albeit wonderfully for the literary imagery) are also and/or therefore deemed “gregarious”—that are devilish inclinations for weeds and spell massive problems for far more than my little yard.

* North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, available ~~HERE~~; CABI Digital Library, available ~~HERE~~ ; Invasive.Org, available ~~HERE~~ ; |

58)

Ranunculus sardous:

To Return to Page One of the Weed Inventory:

|

© Mélanie Walton, 2022

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by MacHighway