Jean-Paul Sartre ... Nausea ...

Brief Biographical Sketch:

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980):

Born in Paris, Sartre’s father died when he was young; Jean-Paul had a troubled youth, but he was very bright and clever. Despite having to retake his examinations, he graduated from the Ecole Normale Supérier—where he met and became involved for his life, albeit not monogamously, with Simone de Beauvoir, whom we demarcate as the Mother of Feminism—to then take a job teaching at Le Havre. He was not fond of Le Havre at all, and much of the setting of Nausea’s Bouville is said to be based on his impressions of the town. He was then conscripted into the military during WWII as a meteorologist. He was taken prisoner and, interned at a POW camp, finished writing his epic philosophical work, Being and Nothingness (1943). Upon his release, he returned to France and joined the French Resistance. These experiences influenced him deeply, and we see the strong expression of a concern for freedom and humanity in all of his writings. After Liberation, Sartre acquired great fame for his many fiction and philosophical writings, including The Flies, No Exit, Being and Nothingness, Existentialism and Humanism (1945), etc. In 1964 he won, but refused to accept, the Noble Prize in Literature. Towards the end of his life, he experienced increasing blindness (had always had a lazy eye); he left the remaining, planned two volumes of his five-volume set of writings on Flaubert unfinished, passing away in 1980. His funeral was attended by over 50,000 people.

Further Resources:

{{ Biographic & Philosophic Overview }} {{ Another Biographic & Philosophic Overview }}

{{ On His Nobel Prize }}

{{ BBC Podcast on Sartre }} {{ BBC Podcast on Existentialism }}

Born in Paris, Sartre’s father died when he was young; Jean-Paul had a troubled youth, but he was very bright and clever. Despite having to retake his examinations, he graduated from the Ecole Normale Supérier—where he met and became involved for his life, albeit not monogamously, with Simone de Beauvoir, whom we demarcate as the Mother of Feminism—to then take a job teaching at Le Havre. He was not fond of Le Havre at all, and much of the setting of Nausea’s Bouville is said to be based on his impressions of the town. He was then conscripted into the military during WWII as a meteorologist. He was taken prisoner and, interned at a POW camp, finished writing his epic philosophical work, Being and Nothingness (1943). Upon his release, he returned to France and joined the French Resistance. These experiences influenced him deeply, and we see the strong expression of a concern for freedom and humanity in all of his writings. After Liberation, Sartre acquired great fame for his many fiction and philosophical writings, including The Flies, No Exit, Being and Nothingness, Existentialism and Humanism (1945), etc. In 1964 he won, but refused to accept, the Noble Prize in Literature. Towards the end of his life, he experienced increasing blindness (had always had a lazy eye); he left the remaining, planned two volumes of his five-volume set of writings on Flaubert unfinished, passing away in 1980. His funeral was attended by over 50,000 people.

Further Resources:

{{ Biographic & Philosophic Overview }} {{ Another Biographic & Philosophic Overview }}

{{ On His Nobel Prize }}

{{ BBC Podcast on Sartre }} {{ BBC Podcast on Existentialism }}

On Nausea (1938):

Sketchy Outline:

Outline, per Roquentin’s Diary Entries:

{pp. 1-178 , per pagination of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea, trans. Lloyd Alexander (NY: New Directions, 1969), isbn: 978-0811217002}

{pp. 1-178 , per pagination of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea, trans. Lloyd Alexander (NY: New Directions, 1969), isbn: 978-0811217002}

- Editor’s note (p.1):

- Starting the diary (pp.1-3):

- Monday, 29 January, 1932 (4-6): change;

- Tuesday, 30 Jan (6-11): witness; can’t pick up paper; lack of freedom;

- Thursday Morning in the Library (11) & Thursday Afternoon (12-4): Lucie; questions proof;

- Friday (14-8) & 5.30 (18-27): face in mirror; first full case of nausea, Madeleine & Adolphe in bar; music; Lucie on street;

- Thursday, 11.30 (27-9) & 3.00 p.m. (29-30): beginning at beginnings; Self-Taught Man’s reading method;

- Friday, 3.00 p.m. (30-8): loss of sense of time; stories and pictures of adventures; beginnings;

- Saturday noon (38-40): on living

- Sunday (40-56): people on streets (Rue Tournebride); people in café; back to streets

- Monday (56-7) & 7.00 p.m. (57-8) & 11.00 p.m. (59): caution of literature versus pure description;

- Shrove Tuesday (59-70): letter from Anny;

- Wednesday & Thursday (70):

- Friday (70-81): fear M. Fasquelle (barman) is dead; panic in streets; reduction of objects by gaze; stops Self-Taught Man from ‘flashing’;

- Saturday Morning (81) & Afternoon (82-94): museum; duty and rights;

- Monday (94-103): quits writing book on Rollebon; nothingness; existence; nausea; music;

- Tuesday (103) & Wednesday (103-126): humanism; nausea, park;

- 6.00 p.m. (126-35): absurdity; contingency;

- Night (135) & Friday (135) & Saturday (135-54): decision; Anny;

- Sunday (154-6):

- Tuesday, in Bouville (156-60): freedom; absurdity;

- Wednesday, My last day in Bouville (160-9) & One Hour Later (169-78): Self-Taught Man pedophilia; intentionality; epoché; choice and values; music.

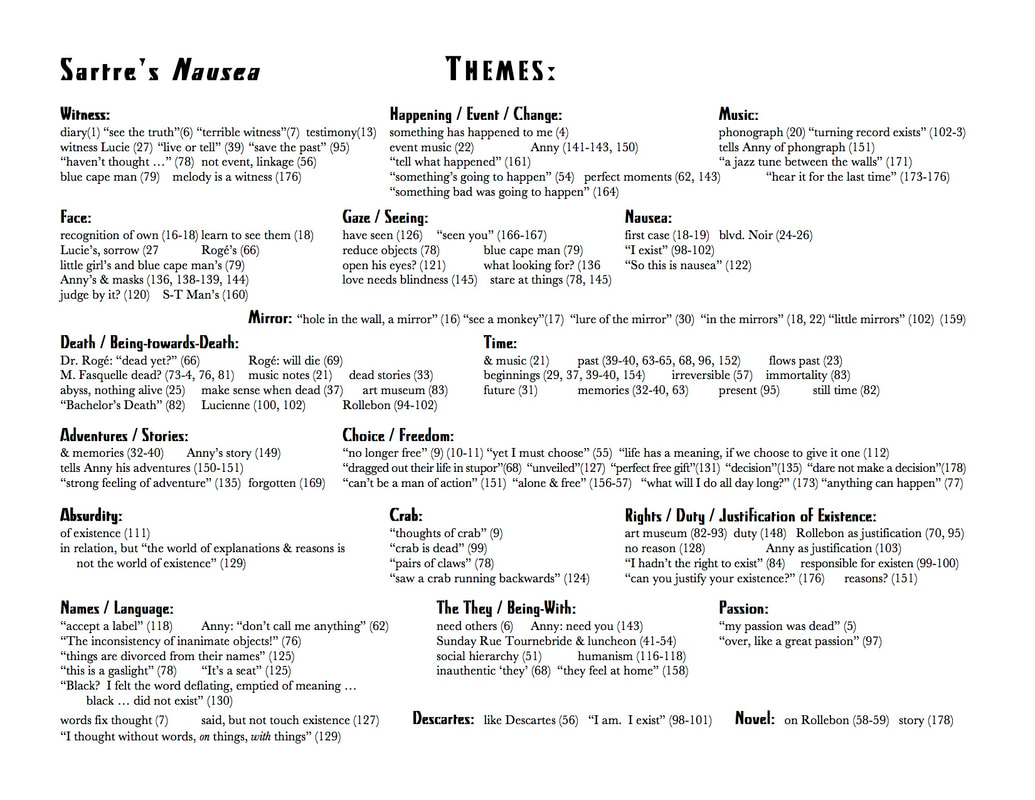

Themes:

Main & Minor Characters:

- Antoine Roquentin: The author of the diary.

- Marquis de Rollebon: The “historical” marquis and subject of Roquentin’s book (p.58); ugly but seductive (12).

- The Self-Taught Man: Ogier P. A man met in the library (4), he is reading all of the books in the library in alphabetical order (30), he is a socialist and a humanist (115-23), he desires adventure (34-6).

- The Man from Rouen: Small, clean man with a black moustache and wig, a commercial traveler who stays in the same hotel as Roquentin (3).

- Lucie: A woman who lives in the building of Roquentin, has a miserable home life, bound by her fate and her husband, polishes steps, complains (11), experiences misery in the dark street (27).

- M. Fasquelle: The owner of the Café Mably (6).

- Mme. Florent: The red haired cashier who is rotting quietly under her skirts in the Café Mably (55).

- Françoise: Woman owner of the Railwaymen’s Rendezvous, sleeps with Roquentin (6-7, 59).

- Madeleine: Waitress/bartender at Railwayman’s Rendezvous, plays the record for Roquentin (18, 173).

- Adolphe: Madeleine’s cousin, a barkeep at Railwaymen’s Rendezvous, purple suspenders (19).

- Anny: Old lover of Roquentin, he constantly has memories of her, receives letter from her to meet again (7, 33, 57, 60-1).

- Doctor Rogé: Man in the café (65).

- M. Achille: Man in the café (64).

- The Blue Cape Man: The flasher lurking the streets (75, 77, 79).

Antoine Roquentin… who, what, where, when, why, how?

Who: historian, writer, neither a real young nor real old man, French, world traveler who spent six years traveling before settling (for three years) in Bouville doing research for his book. Early in the story he takes pride in his travels, later he questions the meaning of experience and adventure. He lives alone, and has very little interaction with people (6).

What: historian, writer, a man who questions

Where: Bouville, France* and then later Paris; staying at Hotel Printania (9).

When: In Bouville for three years, approximately January 1932

Why: for research and to finish his book on the Marquis de Rollebon.

How: The first thing we notice about the story is that it begins with “editors” who claim they have published intact the diary of one Antoine Roquentin. Why this literary device?* Is there an intent for Sartre to distance himself, allow a story to be told through the diary of Roquentin that may or may not depict an existentialist 'hero'? Scientific objectivity in itself put to a test? Device has a long history, i.e. Kierkegaard, could it be a homage or use its allusions to carry in philosophical premises? etc. etc.

What: historian, writer, a man who questions

Where: Bouville, France* and then later Paris; staying at Hotel Printania (9).

- * Bouville is a real place in the Alsace region, but Sartre is inventing the city for his character based upon his experience teaching in Le Harve. Ville de boue, the city of mud

When: In Bouville for three years, approximately January 1932

Why: for research and to finish his book on the Marquis de Rollebon.

How: The first thing we notice about the story is that it begins with “editors” who claim they have published intact the diary of one Antoine Roquentin. Why this literary device?* Is there an intent for Sartre to distance himself, allow a story to be told through the diary of Roquentin that may or may not depict an existentialist 'hero'? Scientific objectivity in itself put to a test? Device has a long history, i.e. Kierkegaard, could it be a homage or use its allusions to carry in philosophical premises? etc. etc.

- * compare, e.g., to its famous use by Søren Kierkegaard, the Danish philosopher and theologian (existentialist forebearer). Kierkegaard wrote most of his philosophic works under pseudonyms, often using several names at the same time. For example, in his famous tome Either/Or, has a pseudonymous editor who has collected three pseudonymous collections, “A’s” essays are first, then there is a famous “Seducer’s Diary,” said to be the diary of a man given to another man, then found in a desk, and then edited by two publishers, and finally letters from “B” to “A.” This means that Kierkegaard himself is three to five places to removed from the writing of the work.

To bear WITNESS to himself ...

“Witness” comes from the Old English word “wit” which means knowledge. So a witness is a person with a knowledge of something—wherein, knowledge is intentional, unlike wisdom; it dictates a relation of a subject and object.

Is witnessing certain? (“Seeing is believing?”) Often, several witnesses to a single crime report seeing different things; later, they may remember more or differently. Psychologically, we call this “closure,” when the mind fills in the gaps in the story to make it complete. So, can we say that a witness imparts his/her own truth? This relativity of truth is discordant to the minds of scientists or historians who are looking for facts or philosophers who are looking for ‘Truth’ … Although perhaps is the most widespread notion today … Roquentin wants The Truth … Nevertheless, Roquentin notes: “… you’d make a terrible witness” (7). Roquentin describes himself as having had a life where all events just flow, in his past it seems that he got caught in the flow of them, and now they just flow past him. He says he would make a terrible witness (7).

The larger question: Can one even be a witness to oneself? Can a diary be a self-witnessing? Doesn’t the whole idea of ‘witness’ mean that there is a seer and a seen; how can one person be both? To be both requires duplicity: the self needs to be an other to itself. Psychologically, we would call this “disassociation” or “Schizophrenia” or “multiple personality disorder” or madness … But … Roquentin rules out insanity (2). To be a witness to the self may be the most essential human command. We will read about Socrates’ divine instruction: “know thyself.”

Roquentin wants to know: What is Changing … At first he blames change on external things--his hands, the fork, the doorknob (4) that feel different; but his fear tells us it is he who is changing.

He wants to find, from the diary exercise, something certain for him to hold on to--a fact, a truth … he grasps on to routine, repetition, for stability; he watches the trams come and go, listens for the commercial traveler to come to the hotel just like normal, etc. to convince himself all is normal. This prompts the question: is observation and description ever wholly objective? Or, does the fact of seeing something and describing it, change what it means and what it is? There is a possibility of this objectivity, as when he sees Lucie in the street (pp.26-7): he is on the “objective” outside witnessing her transfiguration. However, the rarity of observation having no impact, and his inability to easily grasp some certainty or fixed truth, leads him to question the very nature of all facts and the premises of history itself (13).

Finally, though, he has to admit that it is he himself who has changed (4). His fear is that he is no longer free. He wants to do things, for example, when he wants to throw a stone in the water and cannot (2), or when he wants to pick up a piece of paper from the ground and finds himself unable to (9). He cannot understand why, just that he no longer feels free (freedom is an important theme throughout), no longer able to do what he wills (9-10).

He ends this thought by saying: “Objects should not touch because they are not alive” (p.10). This invokes one of the radical claims of phenomenology. The natural attitude posits us as the ones full of blood and DNA, spirit and soul and life and mind—objects are supposed to be inanimate. A table cannot speak to you; a piece of paper cannot touch you. But, when we suspend these presumptions, look at the table or paper with naked eyes, it is not subject looking at object; instead, it is two subjects engaging each other. The paper presents itself to us as actively as we present ourselves to it.

Roquentin is sensing that things have as much or maybe more ‘will’ than he does right now. He wants to view them only as inanimate useful things, as tools, which one uses and puts away and away they should stay. But instead, they are touching him. These things are calling forth his attention as a person would. They are giving him nausea.

Is witnessing certain? (“Seeing is believing?”) Often, several witnesses to a single crime report seeing different things; later, they may remember more or differently. Psychologically, we call this “closure,” when the mind fills in the gaps in the story to make it complete. So, can we say that a witness imparts his/her own truth? This relativity of truth is discordant to the minds of scientists or historians who are looking for facts or philosophers who are looking for ‘Truth’ … Although perhaps is the most widespread notion today … Roquentin wants The Truth … Nevertheless, Roquentin notes: “… you’d make a terrible witness” (7). Roquentin describes himself as having had a life where all events just flow, in his past it seems that he got caught in the flow of them, and now they just flow past him. He says he would make a terrible witness (7).

The larger question: Can one even be a witness to oneself? Can a diary be a self-witnessing? Doesn’t the whole idea of ‘witness’ mean that there is a seer and a seen; how can one person be both? To be both requires duplicity: the self needs to be an other to itself. Psychologically, we would call this “disassociation” or “Schizophrenia” or “multiple personality disorder” or madness … But … Roquentin rules out insanity (2). To be a witness to the self may be the most essential human command. We will read about Socrates’ divine instruction: “know thyself.”

Roquentin wants to know: What is Changing … At first he blames change on external things--his hands, the fork, the doorknob (4) that feel different; but his fear tells us it is he who is changing.

He wants to find, from the diary exercise, something certain for him to hold on to--a fact, a truth … he grasps on to routine, repetition, for stability; he watches the trams come and go, listens for the commercial traveler to come to the hotel just like normal, etc. to convince himself all is normal. This prompts the question: is observation and description ever wholly objective? Or, does the fact of seeing something and describing it, change what it means and what it is? There is a possibility of this objectivity, as when he sees Lucie in the street (pp.26-7): he is on the “objective” outside witnessing her transfiguration. However, the rarity of observation having no impact, and his inability to easily grasp some certainty or fixed truth, leads him to question the very nature of all facts and the premises of history itself (13).

Finally, though, he has to admit that it is he himself who has changed (4). His fear is that he is no longer free. He wants to do things, for example, when he wants to throw a stone in the water and cannot (2), or when he wants to pick up a piece of paper from the ground and finds himself unable to (9). He cannot understand why, just that he no longer feels free (freedom is an important theme throughout), no longer able to do what he wills (9-10).

He ends this thought by saying: “Objects should not touch because they are not alive” (p.10). This invokes one of the radical claims of phenomenology. The natural attitude posits us as the ones full of blood and DNA, spirit and soul and life and mind—objects are supposed to be inanimate. A table cannot speak to you; a piece of paper cannot touch you. But, when we suspend these presumptions, look at the table or paper with naked eyes, it is not subject looking at object; instead, it is two subjects engaging each other. The paper presents itself to us as actively as we present ourselves to it.

Roquentin is sensing that things have as much or maybe more ‘will’ than he does right now. He wants to view them only as inanimate useful things, as tools, which one uses and puts away and away they should stay. But instead, they are touching him. These things are calling forth his attention as a person would. They are giving him nausea.

The Reflection of his FACE ...

The Reflection of his FACE … the question of IDENTITY … a prelude to nausea …

On pages 16-18, Roquentin’s face becomes a foreign thing torturing him; it is him, yet it is not a firm enough truth. He experiences, variously, indifference, confusion, boredom, disgust (31), and sheer terror over this reflection of his face. Why? What does a face represent?

Social scientists will tell us that the face is intimately linked to identity: a face is the person. The body is important, but it is the face that contains the most expression (physical and mental). The face reveals the mind and body. Darwin’s book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animal. According to scientists and animal behaviorists, only chimps and humans can recognize a mirror reflection of a face as their own. (Smokey fighting and loving his mirror).

Nothing firm about his face; it does not make sense to him:

Roquentin cannot see his face as anything certain: as his own, as beautiful or ugly, as anything, it does not make sense to him (16-7).

Roquentin stares at his face in the mirror, he presses closer and closer to it, pressing the mirror. He is experiencing an extreme close-up of his face.*

What would make something seem human? Recognition: Recognizing another as human is an ethical act. Even if the recognition leads to aggression, this is still ethical—it is a recognition of your humanity; would you have any need to fight or love a tree stump? No, emotive responses are mostly shown to other humans). We will read Hegel and Nietzsche on this later, about how all civilization begins with the desire for recognition as a human.

Roquentin admits that he is put to sleep by the reflection of his face:

On the one hand, he is mesmerized by the incomprehensibility of his face. On the other hand, he is bored by it, a face is supposed to engage you, his does not. His is not firm enough to express anything he desires it too.

He says that people who live in society must learn how to see faces.

He lives alone; he has not learned how to see faces. When people are very public, they learn to see their own faces in a mirror as other people see their faces; to read themselves through how other people read their face. Their faces become that through which they interact with the world of people (18). Deleuze proposed that the face is like a MAP.

Roquentin’s face doesn’t give him any directions.

“The unexamined life is not worth living” (Socrates, Plato’s Apology).

Witness:

Nausea and Music:

On pages 16-18, Roquentin’s face becomes a foreign thing torturing him; it is him, yet it is not a firm enough truth. He experiences, variously, indifference, confusion, boredom, disgust (31), and sheer terror over this reflection of his face. Why? What does a face represent?

Social scientists will tell us that the face is intimately linked to identity: a face is the person. The body is important, but it is the face that contains the most expression (physical and mental). The face reveals the mind and body. Darwin’s book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animal. According to scientists and animal behaviorists, only chimps and humans can recognize a mirror reflection of a face as their own. (Smokey fighting and loving his mirror).

Nothing firm about his face; it does not make sense to him:

Roquentin cannot see his face as anything certain: as his own, as beautiful or ugly, as anything, it does not make sense to him (16-7).

Roquentin stares at his face in the mirror, he presses closer and closer to it, pressing the mirror. He is experiencing an extreme close-up of his face.*

- * Face as a SCREEN of the movie of the person … THE CLOSE-UP: did we ever really see the face before the photograph, or especially, before film where the extreme close-up shot allowed us to see the face in a way we had never before?

What would make something seem human? Recognition: Recognizing another as human is an ethical act. Even if the recognition leads to aggression, this is still ethical—it is a recognition of your humanity; would you have any need to fight or love a tree stump? No, emotive responses are mostly shown to other humans). We will read Hegel and Nietzsche on this later, about how all civilization begins with the desire for recognition as a human.

Roquentin admits that he is put to sleep by the reflection of his face:

On the one hand, he is mesmerized by the incomprehensibility of his face. On the other hand, he is bored by it, a face is supposed to engage you, his does not. His is not firm enough to express anything he desires it too.

He says that people who live in society must learn how to see faces.

He lives alone; he has not learned how to see faces. When people are very public, they learn to see their own faces in a mirror as other people see their faces; to read themselves through how other people read their face. Their faces become that through which they interact with the world of people (18). Deleuze proposed that the face is like a MAP.

Roquentin’s face doesn’t give him any directions.

“The unexamined life is not worth living” (Socrates, Plato’s Apology).

Witness:

- Identity.

- Diary (witness to self) (p.1).

- Witness to Lucie in the street (p.27).

- Witness to self, Quotes around underwater lines (p.78).

- Melody is a witness (p.176).

Nausea and Music:

- Identity.

- Lack of Freedom/Will (Existence precedes Essence; Authenticity & Inauthenticity).

- Music: Is the medium by which we can express the most powerful and essential reflections.

- Time: Beginnings (music/adventure). Struggles with writing (living paradox). Being-towards-death. Structures our consciousness.

- Language: Naming: Structures our identity as time structures our consciousness.

Being-in-the-World, Bring-towards-Death, and Being-With ...

Moving from the exploration of how Roquentin’s existential anxiety is like a humanization of the phenomenological shift from the natural attitude (where we live in the world not theorizing) to the phenomenological attitude (where we bracket all bias and see our interaction with the world through new eyes) ...

To fill this humanization out a little more, think about the characterization of existence--its fundamental structures--given us by Martin Heidegger: Being-in-the-World, Bring-towards-Death, and Being-With.

Being-in-the-World is the feeling of our “thrownness” into the world. We are suddenly tossed, without meaning or design, into existence—this is the opposite of the enlightenment ideal of the all-powerful man over nature, conquering attitude and the opposite of the idea of the active subject in the passive world--recall Roquentin’s feeling that things are touching him instead of he touching things.

We will come back to the idea of Being-towards-Death shortly when we consider the role of music …

Being-With is a characteristic that acknowledges how much the other effects the definition of the self—we do not exist like a solitary ego in the world, we are formed by our interaction with others, especially through discourse.

BUT… We learn that Roquentin lives by himself and has little contact with other people (6): his girlfriend is long gone; his current affair is a catharsis, but not love or connection or passionate; the Self-Taught Man, whom he talks with the most, still cannot be described as a friend; he has more invested in the Marquis de Rollebon than any living being--recall that he called the dark and abandoned streets the ultimate purity (pp.24-7).

But this does not entirely condemn Roquentin because Being-With has a double edge: As much as the world and others form who we are, if we are entirely wrapped up in the world with other people, it is harder to step outside of the everydayness and look at the world, self, and other differently.

Not just the obvious social relationships but also LANGUAGE itself makes it harder to think otherwise—on page 7 Roquentin lets himself slip away from language, he doesn’t try to think about words. WHAT DO WORDS DO? They define things, classify, explain, grant more stable existence to things.

So… WHAT HAS HAPPENED? Roquentin is experiencing a break from the Natural Attitude. He is experiencing a change he cannot understand, and is trying to write about it to understand it—trying to rationalize, put into words what is going on. He is loosing touch with his IDENTITY—the identity that is constructed by the world and others.

To fill this humanization out a little more, think about the characterization of existence--its fundamental structures--given us by Martin Heidegger: Being-in-the-World, Bring-towards-Death, and Being-With.

Being-in-the-World is the feeling of our “thrownness” into the world. We are suddenly tossed, without meaning or design, into existence—this is the opposite of the enlightenment ideal of the all-powerful man over nature, conquering attitude and the opposite of the idea of the active subject in the passive world--recall Roquentin’s feeling that things are touching him instead of he touching things.

We will come back to the idea of Being-towards-Death shortly when we consider the role of music …

Being-With is a characteristic that acknowledges how much the other effects the definition of the self—we do not exist like a solitary ego in the world, we are formed by our interaction with others, especially through discourse.

BUT… We learn that Roquentin lives by himself and has little contact with other people (6): his girlfriend is long gone; his current affair is a catharsis, but not love or connection or passionate; the Self-Taught Man, whom he talks with the most, still cannot be described as a friend; he has more invested in the Marquis de Rollebon than any living being--recall that he called the dark and abandoned streets the ultimate purity (pp.24-7).

But this does not entirely condemn Roquentin because Being-With has a double edge: As much as the world and others form who we are, if we are entirely wrapped up in the world with other people, it is harder to step outside of the everydayness and look at the world, self, and other differently.

Not just the obvious social relationships but also LANGUAGE itself makes it harder to think otherwise—on page 7 Roquentin lets himself slip away from language, he doesn’t try to think about words. WHAT DO WORDS DO? They define things, classify, explain, grant more stable existence to things.

So… WHAT HAS HAPPENED? Roquentin is experiencing a break from the Natural Attitude. He is experiencing a change he cannot understand, and is trying to write about it to understand it—trying to rationalize, put into words what is going on. He is loosing touch with his IDENTITY—the identity that is constructed by the world and others.

“Existence precedes essence” & Authenticity and Inauthenticity

Like Heidegger, Sartre denies that there is an essence predetermining our existence. This means that Sartre denies that there is any sort of telos (Greek, “end,” “purpose,” or “goal”), like a predefined human essence, a soul, a philosophy of determinism, etc. which could determine our meaning, what we should do, or who we are.

Instead, he believes that our existence is what determines our essence, or, who we are.

In the story, we see Roquentin beginning to realize that he had thought his socially defined existence WAS his essence—his OWN identity. Now this “essence” is crumbling.

For Sartre, without determinism (pre-given essence to define us) we experience existential angst (for 2 reasons):

1) Nothing outside of ourselves tells us what to do, or even makes it the case that we should do one thing rather than another.

2) We do not know what will happen to us once we are gone.

Existential Angst has been characterized by Kierkegaard and Heidegger as like the experience of being hung out over a great ABYSS. We look down, the feeling is beyond fear; we feel deep, dark anxiety. It makes us dizzy, nauseous.

The only way to pull oneself back from this dizzying abyss is to accept the paradox of meaning and existence; to freely choose in awareness of the possible meaninglessness of your choice.

What does this mean? Look at Roquentin: he thought he knew who he was (a historian, a world traveler, a 30-something redheaded French man), but … he is becoming aware that this existence is inauthentic--his essence is not determined by his work, his age, his nationality, his gender, etc. …

His real essence is unknown to him because he has not yet made his essence; he must make his essence by how he lives; to do this authentically, he needs to be the one to resolutely choose his way of existing.

BUT … This awareness of one’s own inauthenticity makes one also aware of the great paradox of existence: he did not freely choose who he is but actual free choice may be meaningless despite the absolute requirement that one must take responsibility for the self and choose one’s identity or else one cannot live an authentic life.

But … no matter how many scientists or psychologists or philosophers or theologians or television commercials tell us to CHOOSE, to BE AUTHENTIC … This is neither easy nor common … in fact, as we see for Roquentin, it is TERRIFYING.

Instead, he believes that our existence is what determines our essence, or, who we are.

In the story, we see Roquentin beginning to realize that he had thought his socially defined existence WAS his essence—his OWN identity. Now this “essence” is crumbling.

For Sartre, without determinism (pre-given essence to define us) we experience existential angst (for 2 reasons):

1) Nothing outside of ourselves tells us what to do, or even makes it the case that we should do one thing rather than another.

- i.e., things are not embedded with values (return money).

- i.e., things do not derive value from human nature or God.

- Instead, we make values and ourselves by choices.

2) We do not know what will happen to us once we are gone.

- The fear for the unknown.

- Being-towards-death (we know we are not god, hence we are mortal, we will die; But, we do not know when or where or how; this obsesses us, and it scares us).

Existential Angst has been characterized by Kierkegaard and Heidegger as like the experience of being hung out over a great ABYSS. We look down, the feeling is beyond fear; we feel deep, dark anxiety. It makes us dizzy, nauseous.

- Kierkegaard is led to this abyss by the question of faith.

- Heidegger is led to the abyss by the question of being.

- Roquentin is at the edge of the abyss, nauseous, for more than the question of being in general; he is there for the question of being-in-the-world, for living.

The only way to pull oneself back from this dizzying abyss is to accept the paradox of meaning and existence; to freely choose in awareness of the possible meaninglessness of your choice.

What does this mean? Look at Roquentin: he thought he knew who he was (a historian, a world traveler, a 30-something redheaded French man), but … he is becoming aware that this existence is inauthentic--his essence is not determined by his work, his age, his nationality, his gender, etc. …

His real essence is unknown to him because he has not yet made his essence; he must make his essence by how he lives; to do this authentically, he needs to be the one to resolutely choose his way of existing.

BUT … This awareness of one’s own inauthenticity makes one also aware of the great paradox of existence: he did not freely choose who he is but actual free choice may be meaningless despite the absolute requirement that one must take responsibility for the self and choose one’s identity or else one cannot live an authentic life.

But … no matter how many scientists or psychologists or philosophers or theologians or television commercials tell us to CHOOSE, to BE AUTHENTIC … This is neither easy nor common … in fact, as we see for Roquentin, it is TERRIFYING.

Nausea:

Let us look specifically at the terror; at pages 18-27, which explicate Roquentin’s first full case of nausea that we see. He enters the bar hoping to meet with Françoise for a little loving--his affair may lack passion but does seems to be a catharsis. When he learns that she is not there, he begins to feel a wave of nausea sweep over him.

He sits in the bar unable to deal with the thing that is his beer mug as men play cards next to him. For a while Roquentin cannot take his eyes off of the barman, Cousin Adolphe, and his purple suspenders against his blue shirt. He watches the colors and things roll into one another. The suspenders make themselves visible to him (they “touch” him, re: p. 10).

Bottom of page 19: “The Nausea is not inside me: I feel it out there in the wall, in the suspenders, everywhere around me. It makes itself one with the café, I am the one who is within it.” Nausea (capitalized) is not merely a symptom of the stomach, but a way of being in the world (19-20).

He sits in the bar unable to deal with the thing that is his beer mug as men play cards next to him. For a while Roquentin cannot take his eyes off of the barman, Cousin Adolphe, and his purple suspenders against his blue shirt. He watches the colors and things roll into one another. The suspenders make themselves visible to him (they “touch” him, re: p. 10).

Bottom of page 19: “The Nausea is not inside me: I feel it out there in the wall, in the suspenders, everywhere around me. It makes itself one with the café, I am the one who is within it.” Nausea (capitalized) is not merely a symptom of the stomach, but a way of being in the world (19-20).

Music & Time & Being-Towards-Death:

Pages 21-23 reveal the POWER OF MUSIC over his nausea.*

For Roquentin, the music is connected to memory. Like memory, he can know the tune, but cannot hold on to the notes, on to the event. The notes are born and die. He says he must not only accept their death, but also will it. Without willing their death he has only notes and no melody. Melody is what is created as the notes die, it needs them having passed in order to be a continuum of a melody line.

Isn’t this a fair depiction of TIME? Each note is like a “now” that must past in order for there to be a future and a past. But, further, what if we exist like these notes? What if our being is always Being-Towards-Death, that life can only make sense at the end of it, looking back, but, no one is able to experience their own death. We are forever pointed to the impossible future possibility of knowing what it all means.

Roquentin is intimately tied to TIME: He’s a historian: PAST; He’s keeping a diary: PRESENT; He’s fascinated by beginnings (begin in order to end): FUTURE… BUT… around page 30 his tie to time is slowly being loosened:

READ (“I see the future…”) ¶ on Page 31:

Watching woman walk, reveals Roquentin loosing all sense of time. He cannot separate the future and past and present. Temporal sequence confused.

READ (“For a hundred dead…) ¶ on Page 33:

Telling stories; shows his memories disintegrating by being taken over by words. The sensations of memory are aged to words (hence the past does not exist in and of itself. The thing we call the past is just what we talk about in the grammatical past tense)…

We see this disintegration intensely in the scenes on pp.94-96 where he is trying to write about the Marquis but cannot… he asks: where is the division between the present and the past? Does the present exist? How can it be something that exists that you cannot grab?

On page 95, he says that to be forgotten is to be forsaken in the present. This is a negation of existence to be forgotten.

READ (“I looked anxiously …) end p.95-96.

To him, everything else does not exist. The past does not exist. We believe in it just because it is so hard to imagine nothingness. Things are exactly as they appear, and there is nothing behind them (95-6). –there is no essential meaning embedded in things–

We have already seen (p.68, last ¶) how he talks, almost longingly about those people who can condense their memories, their lived time, down into something to be passed off as wisdom.

This ability is as close as one can come to summarizing one’s life; to be able to look back at a life lived and give it meaning. To give it meaning means to give it closure—the paradox of Being-Towards-Death.

Phenomenology and Time:

Husserl analyzed time as the subjective structure of all human consciousness; it structures as a dynamic flow with interspersed stable positions (the now’s), but it does not flow like a river, forever moving on, instead:

We “live” in the Now that is always slowly moving forward with our ability of Protention (anticipation) and Retention (retained information). All of the immediately attained and retained data is sensuous and always moving backwards.

Heidegger humanizes this model. He agrees that time is subjective [even clock time, which we think is “objective” time is really subjective because it was created by us]. But, he goes further to say that WE (as Dasein) are temporal; we exist as ec-stasis, as a standing-outside of ourselves. We are future oriented.

Sartre copies this idea and calls this way of living pro-jected (forward pushed).

This makes time necessary to our existence, but difficult to explain how it exists. The future, that which IS not yet has more existence to us than the now, which cannot be held on to and more than the past, which becomes re-presented to us.

Roquentin and Time:

Roquentin’s struggle with characterizing time illustrates this paradox. But… when Roquentin damns the past as not existent he kills the Marquis de Rollebon again. He had been living inside of Roquentin for three years, and now he was killed by the realization of the past’s nonexistence. Rollebon returned to his nothingness (96).

Roquentin tries to recall him, but cannot. He only gets an image, a fiction of Rollebon (97). This means that the reason for Roquentin’s existence, for the last three years, has just vanished:

“M. de Rollebon was my partner; he needed me in order to exist and I needed him so as not to feel my existence.” (98).

Now he feels the full force of his existence. We are beginning to see how this feeling is the Nausea:

But first…

Let’s go back to the medicating effects of the Music:

Page 22 brings us to the climax of the music for Roquentin, to the vocal line. The woman’s voice is not necessarily what he craves, but for the event that all of the notes have been building towards. It is like the awaited event that time has been forging towards.

He remarks, “Nothing can interrupt it yet all can break it.” (22). Anything can make the phonograph stop playing, but nothing can stop the voice from singing because it is not a real thing here and now. Its existence is not necessarily spatial.

I think it is also worthwhile to take note of the particular song he chooses. It is the ragtime tune of “Some of These Days.” The words he quotes are: “Some of these days / You’ll miss me honey / And when you leave me.” (22-3).*

It is the first couplet that makes his nausea subside. His body hardens. He is in the music. He is swallowed by the music. His arm reaches for his beer, it looks to him like it is dancing. He takes his beer and drinks. He is happy.

As he listens to the music he defines himself as he who sat on the banks of the Tiber, he who was in Rome, in Barcelona, he who was in Cambodia looking a temple bound by tree roots, he who is sitting here in this bar listening to the woman sing. It is interesting that he is here defining himself, naming his being as a person who has done X, Y, and Z. His image of himself is he who has done a number of things.

Early in the book, this self-definition works (somewhat) to calm his nausea.

The curative powers of this description of his identity dissolves around the same time as he looses the power to keep time in order.

This parallels Time as the structure of consciousness to Language (naming, description) as the structure of identity.

Sartre is proposing either a critique of phenomenology or a “next step.”

Husserl’s goal of the epoché was to describe all that appeared (essence), thus to know it.

Heidegger’s goal may be to use the description to (1) un-do the self in order to (2) come to know the essential self.

Sartre’s goal may be to use the description to (1) un-do the self in order to (2) make the self.

- * Sartre’s influence likely from Nietzsche’s analysis of its transformative powers born from Greek thought. In one aphorism in the Gay Science, Nietzsche has an innovator say to a disciple that he has a thirst for a composer who would take his ideas and turn them into music because music is the most powerful medium, “With music one can seduce men to every error and every truth: who could refute a tone?” (106).

For Roquentin, the music is connected to memory. Like memory, he can know the tune, but cannot hold on to the notes, on to the event. The notes are born and die. He says he must not only accept their death, but also will it. Without willing their death he has only notes and no melody. Melody is what is created as the notes die, it needs them having passed in order to be a continuum of a melody line.

Isn’t this a fair depiction of TIME? Each note is like a “now” that must past in order for there to be a future and a past. But, further, what if we exist like these notes? What if our being is always Being-Towards-Death, that life can only make sense at the end of it, looking back, but, no one is able to experience their own death. We are forever pointed to the impossible future possibility of knowing what it all means.

Roquentin is intimately tied to TIME: He’s a historian: PAST; He’s keeping a diary: PRESENT; He’s fascinated by beginnings (begin in order to end): FUTURE… BUT… around page 30 his tie to time is slowly being loosened:

READ (“I see the future…”) ¶ on Page 31:

Watching woman walk, reveals Roquentin loosing all sense of time. He cannot separate the future and past and present. Temporal sequence confused.

READ (“For a hundred dead…) ¶ on Page 33:

Telling stories; shows his memories disintegrating by being taken over by words. The sensations of memory are aged to words (hence the past does not exist in and of itself. The thing we call the past is just what we talk about in the grammatical past tense)…

We see this disintegration intensely in the scenes on pp.94-96 where he is trying to write about the Marquis but cannot… he asks: where is the division between the present and the past? Does the present exist? How can it be something that exists that you cannot grab?

- On the one hand, he looks at the words he wrote, they look to him as if anyone could have written those lines. As soon as he put them down, they are in the past (95).

On page 95, he says that to be forgotten is to be forsaken in the present. This is a negation of existence to be forgotten.

- On the other hand, in his nervousness he looks around him, and is assaulted by the present. The present, and only the present lurks there, revealing its true nature to him. It is what exists.

READ (“I looked anxiously …) end p.95-96.

To him, everything else does not exist. The past does not exist. We believe in it just because it is so hard to imagine nothingness. Things are exactly as they appear, and there is nothing behind them (95-6). –there is no essential meaning embedded in things–

We have already seen (p.68, last ¶) how he talks, almost longingly about those people who can condense their memories, their lived time, down into something to be passed off as wisdom.

This ability is as close as one can come to summarizing one’s life; to be able to look back at a life lived and give it meaning. To give it meaning means to give it closure—the paradox of Being-Towards-Death.

Phenomenology and Time:

Husserl analyzed time as the subjective structure of all human consciousness; it structures as a dynamic flow with interspersed stable positions (the now’s), but it does not flow like a river, forever moving on, instead:

We “live” in the Now that is always slowly moving forward with our ability of Protention (anticipation) and Retention (retained information). All of the immediately attained and retained data is sensuous and always moving backwards.

Heidegger humanizes this model. He agrees that time is subjective [even clock time, which we think is “objective” time is really subjective because it was created by us]. But, he goes further to say that WE (as Dasein) are temporal; we exist as ec-stasis, as a standing-outside of ourselves. We are future oriented.

Sartre copies this idea and calls this way of living pro-jected (forward pushed).

This makes time necessary to our existence, but difficult to explain how it exists. The future, that which IS not yet has more existence to us than the now, which cannot be held on to and more than the past, which becomes re-presented to us.

Roquentin and Time:

Roquentin’s struggle with characterizing time illustrates this paradox. But… when Roquentin damns the past as not existent he kills the Marquis de Rollebon again. He had been living inside of Roquentin for three years, and now he was killed by the realization of the past’s nonexistence. Rollebon returned to his nothingness (96).

Roquentin tries to recall him, but cannot. He only gets an image, a fiction of Rollebon (97). This means that the reason for Roquentin’s existence, for the last three years, has just vanished:

“M. de Rollebon was my partner; he needed me in order to exist and I needed him so as not to feel my existence.” (98).

Now he feels the full force of his existence. We are beginning to see how this feeling is the Nausea:

- “The thing which was waiting was on the alert, it has pounced on me, it flows through me, I am filled with it. It’s nothing: I am the Thing. Existence, liberated, detached, floods over me. I exist. I exist.” (98).

But first…

Let’s go back to the medicating effects of the Music:

Page 22 brings us to the climax of the music for Roquentin, to the vocal line. The woman’s voice is not necessarily what he craves, but for the event that all of the notes have been building towards. It is like the awaited event that time has been forging towards.

He remarks, “Nothing can interrupt it yet all can break it.” (22). Anything can make the phonograph stop playing, but nothing can stop the voice from singing because it is not a real thing here and now. Its existence is not necessarily spatial.

I think it is also worthwhile to take note of the particular song he chooses. It is the ragtime tune of “Some of These Days.” The words he quotes are: “Some of these days / You’ll miss me honey / And when you leave me.” (22-3).*

- * “Some of These Days” Music and Words by: Shelton Brooks, a Canadian; sung by Sophia Tucker: c.1906 or 1910. Also performed by (sometimes credited to Jimmy Rushing and the Buck Clayton Big Band). Rag time song; it actually has a happy ending to the song, but in its popularity, the happy end was ignored and it became a model for a heart-break song—it is a warning, not a lament. So, obviously Sartre got it wrong when he has Roquentin ponder the lives of the Jewish-American songwriter and African-American singer in NYC; but, nonetheless for the factual mistakes, the image still works well for the story (p.176).

It is the first couplet that makes his nausea subside. His body hardens. He is in the music. He is swallowed by the music. His arm reaches for his beer, it looks to him like it is dancing. He takes his beer and drinks. He is happy.

As he listens to the music he defines himself as he who sat on the banks of the Tiber, he who was in Rome, in Barcelona, he who was in Cambodia looking a temple bound by tree roots, he who is sitting here in this bar listening to the woman sing. It is interesting that he is here defining himself, naming his being as a person who has done X, Y, and Z. His image of himself is he who has done a number of things.

Early in the book, this self-definition works (somewhat) to calm his nausea.

The curative powers of this description of his identity dissolves around the same time as he looses the power to keep time in order.

This parallels Time as the structure of consciousness to Language (naming, description) as the structure of identity.

Sartre is proposing either a critique of phenomenology or a “next step.”

Husserl’s goal of the epoché was to describe all that appeared (essence), thus to know it.

Heidegger’s goal may be to use the description to (1) un-do the self in order to (2) come to know the essential self.

Sartre’s goal may be to use the description to (1) un-do the self in order to (2) make the self.

more on music’s relation to time in Nausea:

Initially, we see how music soothes Roquentin’s nausea by provoking his memory:

What has just happened is that the Nausea has disappeared. When the voice was heard in the silence, I felt my body harden and the Nausea vanish…

I am in the music…

I have had real adventures. I can recapture no detail but I perceive the rigorous succession of circumstances…

Yes, I who loved so much to sit on the banks of the Tiber at Rome, or in the evening, in Barcelona, ascend and descend the Ramblas a hundred times, I, who near Angkor, on the island of Baray Prah-Kan, saw a banyan tree knot its roots about a Naga chapel, I am here, living in the same second as these card players, I listen to a Negress sing while outside roves the feeble night…

The record stops… (p.22-3).

At this point in the story, memory can calm his anxiety because it, like the ability to fix names to objects or to recognize his face, restores “reality,” the however inauthentic reality of his everyday life.

In everyday life, we are intimately connected to time; Roquentin, likewise: He’s a historian (PAST); He’s keeping a diary (PRESENT); He’s fascinated by beginnings (begin in order to end) (FUTURE)…

BUT… around page 30 his tie to time is slowly being loosened:

READ (“I see the future…”) ¶ on Page 31:

Watching old woman walk, reveals Roquentin loosing all sense of time. He cannot separate the future, past, and present: temporal sequence confused.

READ (“For a hundred dead…) ¶ on Page 33:

Telling stories; shows his memories disintegrating by being taken over by words. The sensations of memory are aged to words (hence the past does not exist in and of itself. The thing we call the past is just what we talk about in the grammatical past tense)…

READ (“I looked anxiously…) end Pages 95-96:

Here we see this disintegration intensely when he is trying to write about the Marquis but cannot… he asks: where is the division between the present and the past? Does the present exist? How can it be something that exists that you cannot grab?

Sickness floods over him; it is not Nausea. Instead, he realizes: “Nothing more was left now… It was my fault: I had spoken the only words I should not have said: I had said that the past did not exist. And suddenly, noiseless, M. de Rollebon had returned to his nothingness” (p.96).

The past does not exist. We believe in it just because it is so hard to imagine nothingness. Things are exactly as they appear, and there is nothing behind them (95-6).

Roquentin has just come to realize the existential provocation that there is no essential meaning embedded in things; all meaning is created by human action.

This shift in the story, this realization of the illusion of the past permits Roquentin further enlightenment:

What has just happened is that the Nausea has disappeared. When the voice was heard in the silence, I felt my body harden and the Nausea vanish…

I am in the music…

I have had real adventures. I can recapture no detail but I perceive the rigorous succession of circumstances…

Yes, I who loved so much to sit on the banks of the Tiber at Rome, or in the evening, in Barcelona, ascend and descend the Ramblas a hundred times, I, who near Angkor, on the island of Baray Prah-Kan, saw a banyan tree knot its roots about a Naga chapel, I am here, living in the same second as these card players, I listen to a Negress sing while outside roves the feeble night…

The record stops… (p.22-3).

At this point in the story, memory can calm his anxiety because it, like the ability to fix names to objects or to recognize his face, restores “reality,” the however inauthentic reality of his everyday life.

In everyday life, we are intimately connected to time; Roquentin, likewise: He’s a historian (PAST); He’s keeping a diary (PRESENT); He’s fascinated by beginnings (begin in order to end) (FUTURE)…

BUT… around page 30 his tie to time is slowly being loosened:

READ (“I see the future…”) ¶ on Page 31:

Watching old woman walk, reveals Roquentin loosing all sense of time. He cannot separate the future, past, and present: temporal sequence confused.

READ (“For a hundred dead…) ¶ on Page 33:

Telling stories; shows his memories disintegrating by being taken over by words. The sensations of memory are aged to words (hence the past does not exist in and of itself. The thing we call the past is just what we talk about in the grammatical past tense)…

READ (“I looked anxiously…) end Pages 95-96:

Here we see this disintegration intensely when he is trying to write about the Marquis but cannot… he asks: where is the division between the present and the past? Does the present exist? How can it be something that exists that you cannot grab?

- On the one hand, he looks at the words he wrote, they look to him as if anyone could have written those lines. As soon as he put them down, they are in the past (95).

- On the other hand, in his nervousness he looks around him, and is assaulted by the present. The present, and only the present lurks there, revealing its true nature to him. It is what exists. “The true nature of the present revealed itself: it was what exists, and all that was not present did not exist. The past did not exist” (95-96).

Sickness floods over him; it is not Nausea. Instead, he realizes: “Nothing more was left now… It was my fault: I had spoken the only words I should not have said: I had said that the past did not exist. And suddenly, noiseless, M. de Rollebon had returned to his nothingness” (p.96).

The past does not exist. We believe in it just because it is so hard to imagine nothingness. Things are exactly as they appear, and there is nothing behind them (95-6).

Roquentin has just come to realize the existential provocation that there is no essential meaning embedded in things; all meaning is created by human action.

This shift in the story, this realization of the illusion of the past permits Roquentin further enlightenment:

pp. 98 – 100 : existence : Body & Thought ...

The past’s death—the Marquis de Rollebon’s death permits Roquentin to see that his existence had been given over to Rollebon. Roquentin now becomes aware of his own existence.

“I exist. It’s sweet, so sweet, so slow” (98). He reverts, like a child, to wonderment at his own body, his tongue, his hand on the table before him. The wonderment slowly becomes sinister: he feels the heat of his thigh, the weight of his hand, his sweat, his obesity …

He jumps up, desperate to stop thinking (99). Aware, now, that HE is also his thought, not just this newly seen body. Cogito:

My thought is me: that’s why I can’t stop. I exist because I think… and I can’t stop myself from thinking. At this very moment—it’s frightful—if I exist, it is because I am horrified at existing. I am the one who pulls myself from the nothingness to which I aspire: the hatred, the disgust of existing, there are as many ways to make myself exist, to thrust myself into existence (99-100).

René Descartes’ Cogito Ergo Sum… (1596-1650) Meditations on First Philosophy

For Descartes, the Cogito is a liberating miracle of the power of reason. It is the greatest praise to God for giving us this greatest of all gifts of reason. It affirms the greatness of our existence.

For Sartre, for Roquentin, the Cogito is the most terrifying of realizations. It is indeed liberating, but it reveals that most people do not want to be liberated … recall: ignorance is bliss, the Matrix movie (do you want to know the ugly truth) … Freedom is a burden.

If I exist because I think … there is no superior, divine, ultimate reason for existence, no intelligent nature or being who made us and looks out for us … we are all alone. We have no fates to blame. We are responsible for our own existence.

Notice, how, once he has figured out that his Nausea is tied to the realization of his own responsibility for existing (100, 122), once his reason has figured it out, named its cause, the terror that he feels alternates with shame and disgust.

For example, when he is out to eat with the Self-Taught Man, who has just revealed that he had been a prisoner of war:

He is going to tell me his troubles … I am only too glad to feel pity for other people’s troubles, that will make a change. I have no troubles, I have money like a capitalist, no boss, no wife, no children; I exist, that’s all. And that trouble is so vague, so metaphysical that I am ashamed of it (p.105).

Nevertheless, we have been reading his diary all along. If we give him the benefit of our doubt, and take his words as truth, then we have been witness to his intense terror brought on by the Nausea.

Does knowing Nausea’s cause cure it?

No, certainly not.

Their further dinner conversation is very revealing … yet, also puzzling: The Self-Taught Man offers many remarks that are remarkably close to the premises of existentialism, while Roquentin expresses a version of existentialist thought that is far more pessimistic than many of Sartre’s ideas …

Roquentin has come to the realization that values are not embedded in things, in the world, or in him in any essential, preordained way. In short, Roquentin has come to realize that there is no reason for existing (112).

Outside of religious arguments to the contrary, there is a very strong secular argument against this declaration of valuelessness:

“I exist. It’s sweet, so sweet, so slow” (98). He reverts, like a child, to wonderment at his own body, his tongue, his hand on the table before him. The wonderment slowly becomes sinister: he feels the heat of his thigh, the weight of his hand, his sweat, his obesity …

He jumps up, desperate to stop thinking (99). Aware, now, that HE is also his thought, not just this newly seen body. Cogito:

My thought is me: that’s why I can’t stop. I exist because I think… and I can’t stop myself from thinking. At this very moment—it’s frightful—if I exist, it is because I am horrified at existing. I am the one who pulls myself from the nothingness to which I aspire: the hatred, the disgust of existing, there are as many ways to make myself exist, to thrust myself into existence (99-100).

René Descartes’ Cogito Ergo Sum… (1596-1650) Meditations on First Philosophy

For Descartes, the Cogito is a liberating miracle of the power of reason. It is the greatest praise to God for giving us this greatest of all gifts of reason. It affirms the greatness of our existence.

For Sartre, for Roquentin, the Cogito is the most terrifying of realizations. It is indeed liberating, but it reveals that most people do not want to be liberated … recall: ignorance is bliss, the Matrix movie (do you want to know the ugly truth) … Freedom is a burden.

If I exist because I think … there is no superior, divine, ultimate reason for existence, no intelligent nature or being who made us and looks out for us … we are all alone. We have no fates to blame. We are responsible for our own existence.

Notice, how, once he has figured out that his Nausea is tied to the realization of his own responsibility for existing (100, 122), once his reason has figured it out, named its cause, the terror that he feels alternates with shame and disgust.

For example, when he is out to eat with the Self-Taught Man, who has just revealed that he had been a prisoner of war:

He is going to tell me his troubles … I am only too glad to feel pity for other people’s troubles, that will make a change. I have no troubles, I have money like a capitalist, no boss, no wife, no children; I exist, that’s all. And that trouble is so vague, so metaphysical that I am ashamed of it (p.105).

Nevertheless, we have been reading his diary all along. If we give him the benefit of our doubt, and take his words as truth, then we have been witness to his intense terror brought on by the Nausea.

Does knowing Nausea’s cause cure it?

No, certainly not.

Their further dinner conversation is very revealing … yet, also puzzling: The Self-Taught Man offers many remarks that are remarkably close to the premises of existentialism, while Roquentin expresses a version of existentialist thought that is far more pessimistic than many of Sartre’s ideas …

Roquentin has come to the realization that values are not embedded in things, in the world, or in him in any essential, preordained way. In short, Roquentin has come to realize that there is no reason for existing (112).

Outside of religious arguments to the contrary, there is a very strong secular argument against this declaration of valuelessness:

Out to Lunch ... Humanism:

The Self-Taught Man is the epitome of a humanist (whose humanism is born from war, where humanity replaces God as the object of faith in and after the war camps p.105, 113-4, although he seems to encompass ideas from diverse strains of humanism).

So, when Roquentin muses, in a fit of sardonic laughter, about the absurdity of all these people in the café, eating and drinking, when there is no reason for existence, the S-T Man understands this outburst to be the declaration that there is no value or purpose in life … a pessimism … which he counters with declaring the goal to be humanity … (p.111-2). But this is not exactly Roquentin’s point …

The S-T Man is expressing the view that each person has innate value b/c they are a person; thus, the link of humanity is an essential value (this view led him to socialism, 115, and prevented his suicide).

Roquentin’s view is that essential values are baseless and that they do not exist.

He holds a certain disdain for humanism and, more so, a recognition of the S-T Man’s lack of true faith in the very ideals he is espousing (116-7):

“Is it my fault if, in all that he tells me, I recognize the lack of the genuine article? Is it my fault if, as he speaks, I see all the humanists I have known rise up?” (116)

He delineates the radical humanist, the ‘left’s’ humanist, the communist, the Catholic humanist or the humanism of angels, “Those are the principle roles. But there are others, a swarm of others…” (117); there is the humanist philosopher, the happy humanist, the sober humanist, “They all hate each other: as individuals, naturally not as men” (117).

Why does he have such disdain for humanism?

They are social roles … they are not authentic choices … they place faith blindly.

The S-T Man becomes aggressive, sensing Roquentin’s disdain (117).

He asks why Roquentin writes, asking for whom he writes, he tries to label Roquentin: humanist, misanthrope, anti-humanist … something. He seeks to pin a name onto Roquentin like Roquentin had sought to pin names on his beer mug, his hand, his face, the street lamps … Why do we try to pin names to things? To help us better understand them? To brush them off as known, and not needing further question? To try to fix their existence in or as one identifiable something? Do we not reduce things of their individuality, strip them of their being unique, and thus misname them when we do so?

… skipping ahead …

We see Roquentin try one last time to fix reality with a name … He gets on the Saint-Elémir tram, READ p. 125: “I lean my hand on the seat …”

Several pages before, at p. 122, Roquentin affirms his suspicion: Nausea is existence …

Now, he jumps from the tram (p.126) and finds himself in the PARK:

So, when Roquentin muses, in a fit of sardonic laughter, about the absurdity of all these people in the café, eating and drinking, when there is no reason for existence, the S-T Man understands this outburst to be the declaration that there is no value or purpose in life … a pessimism … which he counters with declaring the goal to be humanity … (p.111-2). But this is not exactly Roquentin’s point …

The S-T Man is expressing the view that each person has innate value b/c they are a person; thus, the link of humanity is an essential value (this view led him to socialism, 115, and prevented his suicide).

Roquentin’s view is that essential values are baseless and that they do not exist.

He holds a certain disdain for humanism and, more so, a recognition of the S-T Man’s lack of true faith in the very ideals he is espousing (116-7):

“Is it my fault if, in all that he tells me, I recognize the lack of the genuine article? Is it my fault if, as he speaks, I see all the humanists I have known rise up?” (116)

He delineates the radical humanist, the ‘left’s’ humanist, the communist, the Catholic humanist or the humanism of angels, “Those are the principle roles. But there are others, a swarm of others…” (117); there is the humanist philosopher, the happy humanist, the sober humanist, “They all hate each other: as individuals, naturally not as men” (117).

Why does he have such disdain for humanism?

They are social roles … they are not authentic choices … they place faith blindly.

The S-T Man becomes aggressive, sensing Roquentin’s disdain (117).

He asks why Roquentin writes, asking for whom he writes, he tries to label Roquentin: humanist, misanthrope, anti-humanist … something. He seeks to pin a name onto Roquentin like Roquentin had sought to pin names on his beer mug, his hand, his face, the street lamps … Why do we try to pin names to things? To help us better understand them? To brush them off as known, and not needing further question? To try to fix their existence in or as one identifiable something? Do we not reduce things of their individuality, strip them of their being unique, and thus misname them when we do so?

… skipping ahead …

We see Roquentin try one last time to fix reality with a name … He gets on the Saint-Elémir tram, READ p. 125: “I lean my hand on the seat …”

Several pages before, at p. 122, Roquentin affirms his suspicion: Nausea is existence …

Now, he jumps from the tram (p.126) and finds himself in the PARK:

The Park Scene ...

Page 126: Roquentin pushes and jumps from the subway. He pushes through a gate. Then he realizes that he is in the park. He drops down to a bench, taking note of the tree trunks, the tree roots, great black knotty hands reaching to the sky and down into the earth. He would like to escape, to fall asleep, but he cannot, he is suffocating. Existence is suffocating him.

“And suddenly, suddenly, the veil is torn away, I have understood, I have seen” (126).

{veil of maya: Maya is the Hindu deity who perpetuates illusion in the phenomenal world; her “veil” is all of the illusions that we take to be real … that is, everything we take as reality. Most importantly, it deludes us by making us believe that the self is independent and individual, thus, hiding the truth that it is part of Brahman, the universal from which Atman, the true self, comes and is part. In Hinduism, the illusions must be seen through in order to achieve Moksha, enlightenment. (For a comparison, see Siddhartha excerpt below ...)}

“And suddenly, suddenly, the veil is torn away, I have understood, I have seen” (126).

{veil of maya: Maya is the Hindu deity who perpetuates illusion in the phenomenal world; her “veil” is all of the illusions that we take to be real … that is, everything we take as reality. Most importantly, it deludes us by making us believe that the self is independent and individual, thus, hiding the truth that it is part of Brahman, the universal from which Atman, the true self, comes and is part. In Hinduism, the illusions must be seen through in order to achieve Moksha, enlightenment. (For a comparison, see Siddhartha excerpt below ...)}

Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse

(tr. H. Rosner). 1951, NY: New Directions; 1971, NY: Bantam Books.

“Siddhartha had one single goal—to become empty, to become empty of thirst, desire, dreams, pleasure and sorrow—to let the Self die. No longer to be Self, to experience the peace of an emptied heart, to experience pure thought—that was his goal. When all the Self was conquered and dead, when all passions and desires were silent, then the last must awaken, the innermost of Being that is no longer Self—the great secret!” (p.14).

“Siddhartha learned a great deal from the Samanas; he learned many ways of losing the Self. He travelled along the path of self-denial through pain, through voluntary suffering and conquering of pain, through hunger, thirst and fatigue… He lost his Self a thousand times and for days on end he dwelt in non-being. But although the paths took him away from Self, in the end they always led back to it … and was again Self and Siddhartha, again felt the torment of the onerous life cycle.” (p.15-6).

“‘Do you think we are any further? Have we reached our goal? … It does not appear so to me, my friend. What I have so far learned from the Samanas, I could have learned more quickly and easily in every inn in a prostitute’s quarter’ … ‘What is meditation? What is abandonment of the Self? … It is a flight from the Self, it is a temporary escape from the torment of the Self.” (p.15-6).

“… I will no longer try to escape from Siddhartha … I will no longer mutilate and destroy myself in order to find a secret behind the ruins … I will learn from myself, be my own pupil; I will learn from myself the secret of Siddhartha. He looked around himself as if seeing the world for the first time. The world was beautiful … and in the midst of it, he, Siddhartha, the awakened one, on the way to himself … It was no longer the magic of Mara, it was no longer the veil of Maya, it was no longer meaningless and the chance diversities of the appearances of the world …” (p.39).

“Siddhartha reached the long river in the wood … He stopped at this river and stood hesitatingly on the bank … Why should he go any further, where, and for what purpose? There was no more purpose; there was nothing more than a deep, painful longing to shake off this whole confused dream … to make an end of this bitter, painful life. There was a tree on the river bank … Siddhartha leaned against it, placed his arm around the trunk and looked down into the green water which flowed beneath him … and was completely filled with the desire to let himself go and be submerged in the water … to destroy the form that he hated! … Then from a remote part of his soul, from the past of his tired life, he heard a sound. It was one word, one syllable, which without thinking he spoke indistinctly, the ancient beginning and ending of all Brahmin prayers, the holy Om, which had the meaning of ‘the Perfect One’ or ‘Perfection.’ At that moment, when the sound of Om reached Siddhartha’s ears, his slumbering soul suddenly awakened and he recognized the folly of his actions … But it was only for a moment … Siddhartha sank down at the foot of the cocoanut tree … he laid his head on the tree roots and sank into a deep sleep … When he awakened … the past now seemed to him to be covered by a veil, extremely remote, very unimportant. He only knew that his previous life … was finished, that it was so full of nausea and wretchedness that he has wanted to destroy it, but that he had come to himself by a river, under a cocoanut tree, with the holy word Om on his lips.” (p.88-90).

(tr. H. Rosner). 1951, NY: New Directions; 1971, NY: Bantam Books.

“Siddhartha had one single goal—to become empty, to become empty of thirst, desire, dreams, pleasure and sorrow—to let the Self die. No longer to be Self, to experience the peace of an emptied heart, to experience pure thought—that was his goal. When all the Self was conquered and dead, when all passions and desires were silent, then the last must awaken, the innermost of Being that is no longer Self—the great secret!” (p.14).

“Siddhartha learned a great deal from the Samanas; he learned many ways of losing the Self. He travelled along the path of self-denial through pain, through voluntary suffering and conquering of pain, through hunger, thirst and fatigue… He lost his Self a thousand times and for days on end he dwelt in non-being. But although the paths took him away from Self, in the end they always led back to it … and was again Self and Siddhartha, again felt the torment of the onerous life cycle.” (p.15-6).

“‘Do you think we are any further? Have we reached our goal? … It does not appear so to me, my friend. What I have so far learned from the Samanas, I could have learned more quickly and easily in every inn in a prostitute’s quarter’ … ‘What is meditation? What is abandonment of the Self? … It is a flight from the Self, it is a temporary escape from the torment of the Self.” (p.15-6).

“… I will no longer try to escape from Siddhartha … I will no longer mutilate and destroy myself in order to find a secret behind the ruins … I will learn from myself, be my own pupil; I will learn from myself the secret of Siddhartha. He looked around himself as if seeing the world for the first time. The world was beautiful … and in the midst of it, he, Siddhartha, the awakened one, on the way to himself … It was no longer the magic of Mara, it was no longer the veil of Maya, it was no longer meaningless and the chance diversities of the appearances of the world …” (p.39).

“Siddhartha reached the long river in the wood … He stopped at this river and stood hesitatingly on the bank … Why should he go any further, where, and for what purpose? There was no more purpose; there was nothing more than a deep, painful longing to shake off this whole confused dream … to make an end of this bitter, painful life. There was a tree on the river bank … Siddhartha leaned against it, placed his arm around the trunk and looked down into the green water which flowed beneath him … and was completely filled with the desire to let himself go and be submerged in the water … to destroy the form that he hated! … Then from a remote part of his soul, from the past of his tired life, he heard a sound. It was one word, one syllable, which without thinking he spoke indistinctly, the ancient beginning and ending of all Brahmin prayers, the holy Om, which had the meaning of ‘the Perfect One’ or ‘Perfection.’ At that moment, when the sound of Om reached Siddhartha’s ears, his slumbering soul suddenly awakened and he recognized the folly of his actions … But it was only for a moment … Siddhartha sank down at the foot of the cocoanut tree … he laid his head on the tree roots and sank into a deep sleep … When he awakened … the past now seemed to him to be covered by a veil, extremely remote, very unimportant. He only knew that his previous life … was finished, that it was so full of nausea and wretchedness that he has wanted to destroy it, but that he had come to himself by a river, under a cocoanut tree, with the holy word Om on his lips.” (p.88-90).

Back to Roquentin's Veil-Lifting ... What does he understand? What has he seen?

Suddenly, the veil is torn away ... he understands, he has seen ... the nausea is not gone, but he now understands it, the nausea is the I, it is his existence.

Page 127:

The words for things had vanished. Their uses vanished. Our points of reference, our means to make sense out of things around us, all had vanished.

Roquentin has a vision. This vision is an awakening into the meaning of being. That before he understood “to be” as “belonging,” as a classification of things: he saw things as tools. He now realizes that the diversity and individuality of things an illusion, a veneer. Existence unveiled itself and he saw it all as the “very paste of things.” Now everything was just brutish masses, naked, frightful, obscene. He wishes that they would exist more politely, less strongly, with more reserve.

Page 128:

Flaunting the abundance of existence. “We are a heap of living creatures, irritated, embarrassed at ourselves, we hadn’t the slightest reason to be there, none of us, each one, confused, vaguely alarmed, felt in the way in relation to the others. In the way: it was the only relation I could establish. …” We are superfluous.