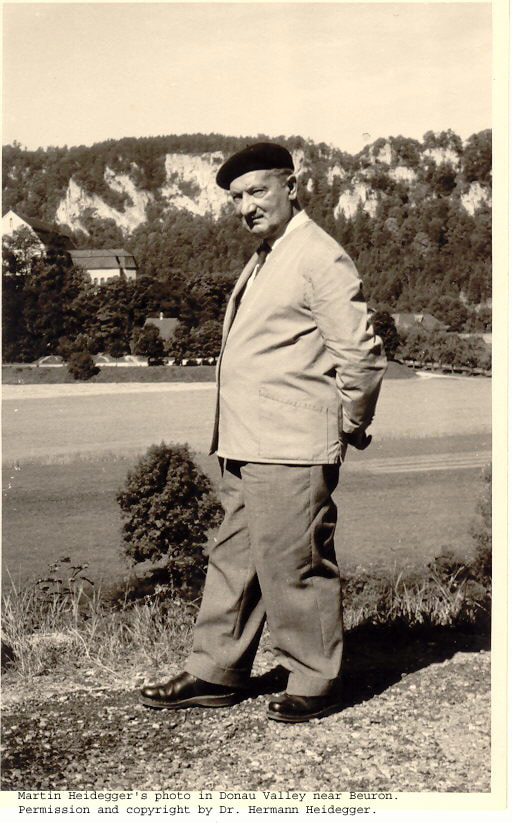

On Martin Heidegger (1889-1976)

“Da-sein is a being

that does not simply occur among other beings.

Rather it is ontically distinguished by the fact that

in its being

this being is concerned about its very being”

--Heidegger, Being and Time, 12

Martin Heidegger was an infinitely influential 20th c. Continental philosopher, notably furthering studies of phenomenology, his philosophical work grounding the development of existentialism, hermeneutics, and postmodernism, aiding the furtherance of critical theory, Marxist philosophy, feminism, race theory, cultural studies, postcolonial studies, and birthing unique fields within aesthetics, environmental philosophy (deep ecology), and architecture. In many ways, however, Heidegger is not an innovator, but leads us to a return to the ancient Greek ideal of philosophy’s intimacy with living the good life that feeds the question of the meaning of Being—a return guided by phenomenological insights as to the cooperative construction of meaning and ways to ask the questions of value. His is a return—but one that is both innovative and profound.

There is a great bias against Heidegger, however, which comes from many fronts (his frustratingly complex style of writing and thinking, his coinage of terms, etc.), but primarily due his blind nationalism: his joining and public endorsement (during a speech given upon receiving an academic position) of the Nazi party. This disgrace is most vivid and all the more indefensible given his long-term love affair with Hannah Arendt, the political philosopher, and his eminent teacher, Edmund Husserl, the father of phenomenology—both Jewish—and the greater clarity his Nazi-sympathetic thoughts have proved to be given the fairly recent publication (spring 2014) of his “black notebooks,” private journals he kept for years in small black-bound writing pads, which contain a few of his attempts to apply his philosophy to Nazi ideological claims about Germans and Jews. The final insult to his critical audience was Heidegger’s complete withdrawal (to a hut in the woods) after the war and his public silence and lack of apology.

While philosophy ought be studied for the value of the ideas themselves--e.g., not throw away Machiavelli for the tyrants who adopt his ideas, Kant or Hegel for their racism, Nietzsche for his use and abuse by the Nazis or his and Otto Weininger’s misogyny, C. S. Pierce for his dissolute life, Bataille or Foucault for their sexual preferences, etc.—it is arguably just as unwise to entirely ignore the person and life from which these ideas come … especially when one is considering thinkers like Heidegger whose phenomenological, ontological, and existential philosophy precisely springs from being subjects embedded in concretely lived lives.

And especially as Heidegger has written: “every metaphysical question can be asked only in such a way that the questioner as such is present together with the question, that is, is placed in question” (“What is Metaphysics?,” Basic Writings, 93), and “We are like plants which—whether we like to admit it to ourselves or not—must with our roots rise out of the earth in order to bloom in the ether and bear fruit” (“Memorial Address,” Discourse on Thinking, 47, wherein he is paraphrasing the poet Johann Peter Hebel), and, most poignantly, “I work concretely and factically out of my ‘I am,’ out of my intellectual and wholly factic origin, milieu, life-contexts, and whatever is available to me from these as a vital experience in which I live” (letter to Karl Löwith, 8/19/1921).

Hence, a brief sketch of his life: Martin Heidegger was born on September 26, 1889 in the Black Forest, in the conservative and rural town of Messkirch, Germany, to a father who was a sexton (caretaker) for the grand St. Martin Church. Heidegger himself entered the seminary to be a Jesuit priest in 1909, but only lasted there for two weeks. His explanation for leaving has been recorded as concerning his heart not being strong enough, and, interestingly, this has led some biographers to say it was his faith that was too weak, others to say it was his physical health that caused the departure (although, he was not unfamiliar with farm labor and loved to ski and hike, forever preferring the country to the city). Immediately after, he entered the University of Freiburg to study theology. Within two years he switched his studies to philosophy. Even before his change of studies, he already had been introduced to philosophy, namely through reading Franz Brentano on Aristotle’s different interpretations of Being and the theologian Carl Braig, also on Being. These studies propelled him to study Aristotle and his medieval interpreters, then Kant and neo-Kantian thinkers on the history of philosophy, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, and then to discover and be entranced by Wilhelm Dilthey’s emphasis on historicity and interpretation and Husserl’s Logical Investigations (1900). His two required theses for his degree were: The Theory of Judgment in Psychologism: A Critical-Positive Contribution to Logic (1913) and Duns Scotus’ Theory of Categories and Meaning (1916). Shortly after graduating, Heidegger married Elfride Petri, his wife for life (despite his known affair with Hannah Arendt in the 1920’s) and mother of his two sons Jörg and Hermann.

There is a great bias against Heidegger, however, which comes from many fronts (his frustratingly complex style of writing and thinking, his coinage of terms, etc.), but primarily due his blind nationalism: his joining and public endorsement (during a speech given upon receiving an academic position) of the Nazi party. This disgrace is most vivid and all the more indefensible given his long-term love affair with Hannah Arendt, the political philosopher, and his eminent teacher, Edmund Husserl, the father of phenomenology—both Jewish—and the greater clarity his Nazi-sympathetic thoughts have proved to be given the fairly recent publication (spring 2014) of his “black notebooks,” private journals he kept for years in small black-bound writing pads, which contain a few of his attempts to apply his philosophy to Nazi ideological claims about Germans and Jews. The final insult to his critical audience was Heidegger’s complete withdrawal (to a hut in the woods) after the war and his public silence and lack of apology.

While philosophy ought be studied for the value of the ideas themselves--e.g., not throw away Machiavelli for the tyrants who adopt his ideas, Kant or Hegel for their racism, Nietzsche for his use and abuse by the Nazis or his and Otto Weininger’s misogyny, C. S. Pierce for his dissolute life, Bataille or Foucault for their sexual preferences, etc.—it is arguably just as unwise to entirely ignore the person and life from which these ideas come … especially when one is considering thinkers like Heidegger whose phenomenological, ontological, and existential philosophy precisely springs from being subjects embedded in concretely lived lives.

And especially as Heidegger has written: “every metaphysical question can be asked only in such a way that the questioner as such is present together with the question, that is, is placed in question” (“What is Metaphysics?,” Basic Writings, 93), and “We are like plants which—whether we like to admit it to ourselves or not—must with our roots rise out of the earth in order to bloom in the ether and bear fruit” (“Memorial Address,” Discourse on Thinking, 47, wherein he is paraphrasing the poet Johann Peter Hebel), and, most poignantly, “I work concretely and factically out of my ‘I am,’ out of my intellectual and wholly factic origin, milieu, life-contexts, and whatever is available to me from these as a vital experience in which I live” (letter to Karl Löwith, 8/19/1921).

Hence, a brief sketch of his life: Martin Heidegger was born on September 26, 1889 in the Black Forest, in the conservative and rural town of Messkirch, Germany, to a father who was a sexton (caretaker) for the grand St. Martin Church. Heidegger himself entered the seminary to be a Jesuit priest in 1909, but only lasted there for two weeks. His explanation for leaving has been recorded as concerning his heart not being strong enough, and, interestingly, this has led some biographers to say it was his faith that was too weak, others to say it was his physical health that caused the departure (although, he was not unfamiliar with farm labor and loved to ski and hike, forever preferring the country to the city). Immediately after, he entered the University of Freiburg to study theology. Within two years he switched his studies to philosophy. Even before his change of studies, he already had been introduced to philosophy, namely through reading Franz Brentano on Aristotle’s different interpretations of Being and the theologian Carl Braig, also on Being. These studies propelled him to study Aristotle and his medieval interpreters, then Kant and neo-Kantian thinkers on the history of philosophy, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, and then to discover and be entranced by Wilhelm Dilthey’s emphasis on historicity and interpretation and Husserl’s Logical Investigations (1900). His two required theses for his degree were: The Theory of Judgment in Psychologism: A Critical-Positive Contribution to Logic (1913) and Duns Scotus’ Theory of Categories and Meaning (1916). Shortly after graduating, Heidegger married Elfride Petri, his wife for life (despite his known affair with Hannah Arendt in the 1920’s) and mother of his two sons Jörg and Hermann.

|

In 1919, Heidegger became Husserl’s assistant at Freiburg and then taught at the University of Marburg (1923-28), where he became a phenomena amongst the students (Hannah Arendt reported “the rumor of a hidden king” and Hans-Georg Gadamer claimed “the boldness and radicality of [his] questioning took one’s breath away”), but was unable to attain a full position twice at the latter due to his lack of publications, but accepted a post at the former when Husserl retired in 1928. Just one year prior, Heidegger published his Being in Time. Its publication was rushed due to his attempt to acquire a full time position, so the first edition contained only two divisions of his planned first part and none of his planned second part; while he pursued many of these same ideas and themes for his entire life, he never completed the work. For the seventh German edition, Heidegger’s preface announced that the notation of “First Half” was deleted, as he knew he would not complete the second half, for it could not be done, he said, without rewriting the entire work. However, he added, the first part’s “path still remains a necessary one even today if the question of being is to move our Dasein” (Being and Time, xxvii).

After the publication of Being and Time, Heidegger’s reputation as a brilliant new force was solidified and renowned widely. Nevertheless, recognition only fueled his personal dissatisfaction with his ideas and his drive to push them further. Unfortunately, his intense desire for intellectual progress was at its height when the National Socialists came to power in 1933. He was recognized as a Nazi-approved rector of the University of Freiburg, and while his dissatisfaction grew quickly (he largely rejected the racism of the ideology, despite there being evidence of his own unexamined prejudices, instead viewing the revolution akin to what was needed philosophically for the question of metaphysics—this period saw his works on Nietzsche and the end of metaphysics and on Hölderlin and the vision of a new order for humanity in the world—hence, he did not support public shows of mindless obedience) and he stepped down from the post a year later, he never officially gave up his membership in the Nazi party. He remained a professor at the University until the war’s end when he was forced out by the French denazification trials of public institutions. He withdrew, sought psychological consultation, and eventually reclaimed his international recognition (perhaps even greater than his first wave of fame) and the right to teach in 1949.

In 1951-52, his first course back in his position at Freiburg was entitled “What is Called Thinking?,” which informed an essay which we will read later in the semester, and signaled the depth and difference of his later thought, which is referred to as the Kehre, the “turn.” (Heidegger himself uses the term Kehre in several different ways, but all far more theoretically than as the label scholars use to simply designate his intellectual changes in his later writings.) In this period, his writing takes on a more poetic, radical but saddened voice about the over-technological obfuscations of basic philosophical questions and ways of life. Jean Beaufret, a French scholar, befriended him and righted his reputation amongst French intellectuals, and was the one who prompted Heidegger to write his “Letter on Humanism” (1947), in which he directly critiques existentialism’s misrepresentations of his philosophy. He also turns his attention to Asian philosophy (he had read Karl Jasper’s translation of Chuang Tzu around 1930, but post-war, he focused more greatly on Chinese philosophy), even working with a Chinese scholar named Hsiao on a translation of the Tao Te Ching (although, Hsiao later reported great concern that Heidegger’s translation was far too interpretative, and he ultimately killed the project).

In his late years, Heidegger spent much of his time in his mountain cabin, travelling (notably several times to Greece), giving a few interviews, and approving the archiving and publication of his Gesamtausgabe, his complete writings. A few days before his death, he wrote down the motto for his collected volumes as “Ways, not works,” and explained that they are a “field of paths of the self-transforming asking of the many-sided question of Being. … The point is to awaken the confrontation about the question concerning the topic of thinking” (Petzet, Encounters and Dialogues, 224). Martin Heidegger died at the age of 86 in 1976. Reportedly, his last living word was “thanks.”

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by MacHighway