Herbert Marcuse’s The Aesthetic Dimension

(Collected in Ross, A&S, pp.548-57)

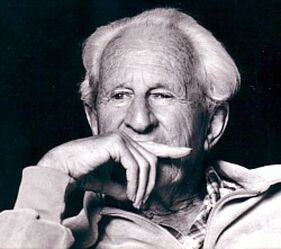

On Herbert Marcuse:

On Critical Theory:

Herbert Marcuse is one of the key figures in Critical Theory. Critical Theory is, most properly, the name of thought produced by the Frankfurt School, which was a 20th c. tradition predominately composed of German philosophers and social theorists whose intellectual areas of study were diverse (including the natural and social sciences), yet shared a basis of Marxist philosophy (most were dissident Marxists who envisioned its improvement) and strong influence by the philosophy of Kant, Hegel, Freud, Weber, and Lukács. They were initially based in the Institute for Social Research (founded in 1923) at the University of Frankfurt; For them, “Critical” Theory had a practical command that traditional theory had neglected: to better the conditions of humans by freeing them from what oppresses and enslaves them. (Although, the term “critical theory” is also used today to designate a method of doing philosophy—typically in applied fields, like gender studies, race studies, etc.—that is inspired by the Frankfurt School.)

Thus, the aims of Critical Theory are to explain the current social reality along with the circumstances of oppression, to be practical, that is, to provide a theory by which to change the current reality, and to be normative, that is, to provide the norms by which it can be criticized and can provide goals for social change. Key figures of or associated very closely to the Frankfurt School include Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin, Herbert Marcuse, Erich Fromm, and, later, Jürgen Habermas.

On Critical Theory:

Herbert Marcuse is one of the key figures in Critical Theory. Critical Theory is, most properly, the name of thought produced by the Frankfurt School, which was a 20th c. tradition predominately composed of German philosophers and social theorists whose intellectual areas of study were diverse (including the natural and social sciences), yet shared a basis of Marxist philosophy (most were dissident Marxists who envisioned its improvement) and strong influence by the philosophy of Kant, Hegel, Freud, Weber, and Lukács. They were initially based in the Institute for Social Research (founded in 1923) at the University of Frankfurt; For them, “Critical” Theory had a practical command that traditional theory had neglected: to better the conditions of humans by freeing them from what oppresses and enslaves them. (Although, the term “critical theory” is also used today to designate a method of doing philosophy—typically in applied fields, like gender studies, race studies, etc.—that is inspired by the Frankfurt School.)

- “Unlike most contemporary theories of society, whose primary aim is to provide the best description and explanation of social phenomenon, critical theories are chiefly concerned with evaluating the freedom, justice, and happiness of societies. In their concern with values they show themselves more akin to moral philosophy than to predictive science” (David Ingram, “Introduction,” in Critical Theory: The Essential Readings (New York: Paragon House, 1992), xx).

Thus, the aims of Critical Theory are to explain the current social reality along with the circumstances of oppression, to be practical, that is, to provide a theory by which to change the current reality, and to be normative, that is, to provide the norms by which it can be criticized and can provide goals for social change. Key figures of or associated very closely to the Frankfurt School include Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin, Herbert Marcuse, Erich Fromm, and, later, Jürgen Habermas.

Background for our selection from Marcuse's The Aesthetic Dimension:

This selection from Marcuse’s The Aesthetic Dimension is perhaps too brief and a bit too choppy, as it is drawn from two different sections of a long, later book. Nevertheless, there are many rich points to draw from the work, and connections to be made with Plato, Tolstoy, Kant, Benjamin, and Adorno, as well as serving to be a nice foreshadowing to the Artist Manifestos we will read as the week moves along.

Given the brevity and choppiness, let me briefly fill out a few important aspects:

- First, Marcuse is grounded in Marxist theory, but he is a severe critic who worked to reject what needed rejection in Marxism, refine what needed refinement, and supplement the gaps so as to improve the theoretical stance. Thus, make sure that you catch how the six delineated points in the first two pages of the selection are Marxist theses, to which Marcuse commands that they must “become again the topic of critical reexamination” (548).

- Second, this ties to a reminder about how Marcuse (like Benjamin and Adorno) are Critical Theorists—the type of philosophical thinking that they do is one that utilizes critique, a negating practice, to produce productive thought that concretely impacts and betters the world. Their task is to use negation productively—keep saying “no!” to sedimented thought and practices that harm, hinder, and oppress; keep saying “no!” so as to inspire movement to a better result. Thus, the frequent language concerning the “critical,” “negation,” and “pessimism” should be read as something that is positive by way of critique.

- Third, in addition to his basis in Marx, Marcuse is also grounded in Freudian psychoanalysis. (Freud himself took much of his inspiration and actual terms and ideas from G. W. F. Hegel, who was the most important guide for Marx.) The Freudian influences we see in this selection include the following:

- An emphasis on emotions and passions (also hearkening Tolstoy): there are frequent mentions of these as positive and overly neglected, especially for their radical and liberating potential, cf. “subjectivity,” 549-50.

- Sublimation: the repression and redirection of base instincts (sex, violence, etc.) to more appropriate avenues (e.g., instead of punching his brother who was teasing him, Billy went outside and chopped all the firewood; instead of committing adultery, Suzy redirects her passion to raising her children, etc.)

- Eros and Thanatos: borrowing them from the Greek pantheon, these become the two basic, primitive, instinctual drives that animate humanity: the erotic/sex drive and the death drive. These are as fundamental to humans as the fight-or-flight instincts are to all animals, and are a spectrum-like dichotomy like the other, too (you do not have the erotic impulse free of all self-destructive impulses and vice versus just like you have something of the very same intensity fueling the fight as the flight).

- Catharsis (an idea much older than Freud, but popularized by him): a release; a cleansing or purification of the self/psyche by releasing repressed emotions; something like a ecstatic purging of what one had bottled up inside which leaves one feeling better, drained in a good way.

Textual Analysis:

- “In a situation where the miserable reality can be changed only through radical political praxis, the concern with aesthetics demands justification” (548).

With this opening quote, we see the intense socio-political dimension Marcuse’s aesthetic theory rests in and his concern to show how aesthetics is practical and utterly beneficial to those drastic climes wherein “radical political praxis” (praxis: practical action) is the only solution. We can imagine the doubt many may have: given the horror about us, we need to mobilize, get into the streets, protest, fight … not make or think about art! Marcuse rejects this. Art is needed for positive political transformation: “art expresses a truth, an experience, a necessity which, although not in the domain of radical praxis, are nevertheless essential components of revolution” (548). Remember, “political” comes from the Greek word polis, a city-state or the citizens therein. The political is about people; art affects people; art thereby affects the polis.

Marcuse then delineates six theses held by Marxist aesthetics. These are the keys that demand a critical reexamination. This is not to say that they are wrong, but Marcuse will submit them to an intense critique and rejection or refinement as needed. In essence, they include:

- (1) art’s connection to the material, hence role in production, which guides social/power structures (bourgeoisie and proletariat, rulers and the oppressed); given art’s connection, it becomes part of the ideology and can lag behind or predict social change.

- (2) art’s connection to class structure (bourgeoisie and proletariat); only proletariat art is authentic.

- (3) the coinciding between aesthetics and politics is between quality and content, respectively (i.e., the how is aesthetic, the what is political).

- (4) artists (the only true ones being proletariat) have an obligation to express the needs of the proletariats.

- (5) the bourgeoisie only produce “decadent art,” which is not authentic.

- (6) realism is the only correct art form because it concretely expresses social relations.

These dictate how the social relations expressed in art must be inherent to art itself (these must inspire and make the work, not be imposed upon it as interpretation after the fact, thus, the artist must be true to these relations, have the proletariat spirit).

Marcuse then explains how these principles from Marx (and Friedrich Engels) have been falsely made into a rigid, falsifying schema (a set of necessary, strict norms or rules) that blindly labels all art as right or wrong, good or bad, emancipatory or oppressive.

When these principles are imposed rigidly and blindly, we have a complete “devaluation” (removing the value from) of subjectivity. In other words, there is a complete loss of the subject, of the people, of humans, and everything that makes us human. “Thereby a major prerequisite of revolution is minimized, namely the fact that the need for radical change must be rooted in the subjectivity of individuals themselves, in their intelligence and their passions, their drives and their goals” (549). Making the rules for art so rigid results in blindness as to what actually drives rebellion: people thinking, knowing, and feeling that conditions, for them, for the ones they love, are wrong and ought to be changed.

Marcuse says some Marxists even think that subjectivity is simply a bourgeois notion--i.e., the bourgeois can see themselves as Billy or Suzy, as free and powerful, but the proletariats must see themselves united as one—and that this is absurd. Not only is it historically inaccurate, but even if it was bourgeois, it would be self-defeating: having a sense of subjectivity (being in touch with your self) is a dangerous, unsettling force that will invalidate any blind-herd mentality. (Hence, the danger of studying philosophy, whose guiding premise is the Socratic “know thyself.”)

So … no, in fact, subjectivity should not be eliminated from aesthetics and/or politics! Thus, subjectivity becomes “liberating subjectivity:” “Liberating subjectivity constitutes itself in the inner history of the individuals—their own history, which is not identical with their social existence” (550). Liberating subjectivity can be alive in any class, and, in fact, works to explode class divisions. “It is all too easy to relegate love and hate, joy and sorrow, hope and despair to the domain of psychology, thereby removing them from the concerns of radical praxis” (550)—all too easy, and yet, Marcuse is telling us, we must not see the emotional, full psychic being of individuals as disconnected from political action. These are the true forces that constitute reality. (This may remind us of Tolstoy’s privilege of emotion in aesthetics.)

Now, we move to and through Marcuse’s own thesis:

- “the radical qualities of art, that is to say, its indictment of the established reality and its invocation of the beautiful image … of liberation are grounded precisely in the dimensions where art transcends its social determination and emancipates itself from the given universe of discourse and behavior while preserving its overwhelming presence” (550).

That is, art has radical qualities—it foments revolution by indicting the way things are by means of conjuring the beautiful, the way things can be. It inspires liberation when it transcends what it is supposed to be (e.g., something pretty to match the couch or sell more cars). In its transcendence, it frees itself from the everyday that is given us, even as it remains before us as awe-inspiring (i.e., it doesn’t transcend so much as to be absent in our world, but remains as something other, yet here before us). Continuing his thesis:

- “Thereby art creates the realm in which the subversion of experience proper to art becomes possible: the world formed by art is recognized as a reality which is suppressed and distorted in the given reality” (550)

By its fact of being other, yet breathtakingly present, it creates its own realm wherein it breaks down our biases and lets us experience art the way it ought to be experienced. For example, no matter how jaded we may be that everything is a commodity, we can experience entering a museum or a going to a show wherein it breaks us free of thoughts about popularity, dress, ticket prices, etc.; it throws us in a state wherein we give ourselves over to the experience of the art, and thereby makes us realize how that ‘world outside’ does put prices and ranks on everything, cheapens and buys and sells everything.

- “This experience culminates in extreme situations (of love and death, guilt and failure, but also joy, happiness, and fulfillment) which explode the given reality in the name of a truth normally denied or even unheard” (550).

This sort of art-experience makes us feel, feel intensely—it affects us in a very basic, human, emotional way (all those emotions we tend to not show in the day to day business of life). To be made to feel serves to explode given reality—we “wake up,” we see how artificial the rat race truly is—we wake up because we are experiencing the truth the rest of life shutters away.

- “The inner logic of the work of art terminates in the emergence of another reason, another sensibility incorporated in the dominate social institutions” (550).

The work of art completes what it is by releasing us from it to go back to the world, but releases us somewhat transformed—we have been given a new perspective, one which we will take with us and work into our everyday experience. And, with this, we have seen his thesis—art is radical: it is something other against the sameness of given reality; it enraptures us, makes us feel, makes us see the falsity of the sameness, and as it releases us, it changes us.

Art has a dimension/function of sublimation and another of criticism (negation):

- Art’s sublimating function: immediate content is taken in and stylized or redirected as directed by the art form—thus, the content of death is drawn so as to be entwined with the need for hope. This gives us the affirmative dimension of art (that which anchors us, gives us a “yes,” a foundation to affirm).

- Art’s critical function: within its very sublimation, the seeds of the critical function rest: by making even death have an aspect of life-affirmation, art gives us a picture different than the one we actually experience on the street or in the war—it gives us a picture to contrast our given reality against, gives us the tools to say “wait, hold on, I want the picture, not this, I will act to change it.” This gives us the critical/negating dimension of art (that which calls us to wake up and shake up the oppressing status quo): “[it] opens a new dimension of experience: rebirth of the rebellious subjectivity” (551).

Aesthetic form: “the result of the transformation of a given content (actual or historical, personal or social fact) into a self-contained whole: a poem, play, novel, etc. … The critical function of art, its contribution to the struggle for liberation, resides in the aesthetic form” (551).

What makes a work of art authentic? For Marcuse, it is not just its content (i.e., does it correctly present the conditions of social oppression or liberation), nor is it just its pure form (i.e., in the pure Kantian sense of the entwining vines free from all concepts); instead, it is “by the content having become form” (551)—by the whole work coming out of the transformed given to be something wholly itself as a work of art, with all of these self-transformative power that creation contains, too. So … art is neither just realistic works of political action nor just of apolitical design.

Thus, we see aesthetic form, freedom, and truth connected. “The truth of art lies in its power to break the monopoly of established reality … to define what is real” (551). It has an emancipatory function and a transformative one—it frees us and it makes our reality a better place.

So … art has the affirmative and negative dimensions (via sublimation and criticism) … Marcuse’s next point is to show that these have no connection to class distinction (i.e., the bourgeoisie say yes, the proletariats say no), but instead relate to something essential in art itself: art’s catharsis. Art provides us this tremendous relief by its power to demystify us—to pull back the curtains about everyday reality and let us see things as they truly are. Affirmation and negation work together in this process—we need both. Another source of the affirmative power of art is in its connection to Eros (the erotic drive, the sex drive, that life-affirming, productive, vehement instinctual drive in us). But, again, “Art stands under the law of the given, while transgressing this law” (552): the affirmative and negative powers must be taken together in a recognition of the power of art.

Marcuse then moves to a reflection on how many will charge that this reading is not accurate to Marx and Engel’s, or that his critique is unfair. (He cites a debate between Adorno and Goldmann as to whether we should “think” art politically/socially or simply take it in, cf. p. 553).

In his critique of the critiques against him, he restates the utter importance of art for political praxis, going so far as calling the necessity of revolution an a priori for art (553). (Remember the term a priori from Kant: it is that which is before experience, an inherent, necessary, pre-given rule.)

He then explains the first main step traditional Marxist aesthetics must take:

- Marxist aesthetics assumes that art is somehow conditioned by class/power/production relations; Marcuse says that it must figure out what this “somehow” is: “that is to say, of the limits and modes of this conditioning” (553). It cannot dismiss the endurance of types of art as some sort of seeing where it all began—it needs to explain why things like Greek tragedy (which held extreme class distinctions) and Medieval epics (which held to ideals of feudalism) are still viewed as beautiful. So, what is the universal “something” these works contain? This universality cannot be explained by class relations. Marxists should not ignore nature in its theory—inherent in this nature they ought to study is the “domain of the primary drives: of libidinal and destructive energy” (554), which are the aforementioned Eros and Thanatos, the sex drive and death drive. “Marxism has too long neglected the radical political potential of this dimension, though the revolutionizing of the instinctual structure is a prerequisite for a change in the system of needs …” (554).

- “In the aesthetic form, the autonomy of art constitutes itself” (554).

We have seen this point earlier in his statement of his own thesis and following definition of “aesthetic form:” it is that result of the everyday reality being transformed and given as a self-contained whole. However, he now adds to this (to hearken his point in the very opening statement of the work) that despite its autonomy, society remains present in the autonomous realm of art. Art is not so “other” that it cannot be beheld in everyday life. ...

... There are three ways that society remains present in art:

- (1) as all of the “stuff” that is transformed in art’s representation (the content that is transformed in the work of art).

- (2) as the scope of possibilities for struggle and liberation.

- (3) as the specific position of art in the divisions of labor, especially between the intellectual and manual, through which art has become something by and for the elites.

These are the ways that we see society in the autonomous realm of art; they are the objective limitations of the autonomy of art, and where we see class divisions. And, these are all areas that demand our critical investigation. The class privilege of an artist does not, for Marcuse, deny the truth or aesthetic quality of his/her art. Neither does the presence or absence of class issues in the content of his/her work deny it its truth and quality. Marcuse writes: “The criteria for the progressive character of art are given only in the work itself as a whole: in what it says and how it says it” (555).

Note how Marcuse leans a little bit in the direction of sounding like Kant here: Art gives itself its own rule by which to judge it. However, Kant would limit the statement more to the “how” than the “what” of its expression. A slight hint of Kant can also be heard in the next lines:

- “In this sense art is ‘art for art’s sake’ inasmuch as the aesthetic form reveals tabooed and repressed dimensions of reality: aspects of liberation” (555).

Marcuse then elaborates this by discussing Benjamin’s intense analyses of Poe, Proust, Valéry, and especially in Baudelaire. In each, there is an expression of “a ‘consciousness of crisis’ … a pleasure in the anomic—the secret rebellion of the bourgeois against his own class” (555). This “secret rebellion” or “secret protest” springs from, according to Benjamin and, more so, Marcuse, the “primary erotic-destructive forces [Eros and Thanatos] which explode the normal universe of communication and behavior” (555)—they are intimately social.

So … we see this radical nature of art, but, note the ending lines of our selection: “Art cannot abolish the social division of labor which makes for its esoteric character, but neither can art ‘popularize’ itself without weakening its emancipatory impact” (556)—and here, we see the same sort of warning broached that was focused upon in Adorno’s essay.

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by MacHighway