Jean-François Lyotard's The Differend . . . << chapters four & five >>

|

For earlier materials, select desired from buttons to right:

|

(I) Review & Overview

Chapter One (“Differend”) showed us what was at risk: the ontological status of the witness (how can one be a witness, which means ‘one with the knowledge of something,’ if one’s knowledge is denied) due to the revisionist’s “logic” requiring crude ontological evidence (‘prove/show it exists,’ which the witness cannot do).

So, Chapter Two (“Referent, Name”) explores what is indicated by the ontological: the referent (that about which a phrase is referring) and the name (a denomination of the referent). In this chapter, we see the many failures in the attempt to verify ontological phrases through linkages with phrases from other genres of discourse; despite all these failures, it ends with the introduction of how the ‘phrase event’ leaves us with a “complex feeling” about that which we have failed to validate.

Chapter Three (“Presentation”), following Two’s succession of failures, begins all over again from One’s problem, like a reset, and explores a different way to verify what we haven’t been able to about the ‘phrase event.’ Instead of trying out a new genre of discourse to express it, it (1) reconsiders how the ‘phrase event’ happens (that the ‘presentation of a phrase’ is an ‘event’ that happens that then requires its ‘situation’); then, (2) realizes that the ontological designations only occur in that subsequent situation; thus, (3) explores if the ‘happening’s happening’ (the eventing of the event or presenting of the presentation) can prove a certain foundation (every event happens TO a subject), and thereby validate the ontological status of the witness; however, (4) discovers how this fails (because the subject does not pre-exist before the event); and therefore (5) establishes how the first two steps (a) involve questions on time because of the before/after of ‘happening’ and ‘situation,’ and how, because of the third step, (b) one must ‘situate’ the happening through linkages, and thus, (c) because the presentation of the phrase is a nebulous event prior to ‘situation,’ and no one situation will capture its entirety, ‘feeling’ needs to lead our attempts at its expression.

Chapter Four (“Result”), like Three, doesn’t exactly pick up from where the previous chapter left off; unlike Three, though, it is not exactly a reset, but a circling around to readdress a dismissed attempt to express what has been silenced: dialectics. In Chapter One’s “Plato Notice,” Socratic dialectics or his style of argument in dialogue was suggested to fail this expression because (in part) it relied upon seduction, persuasion, something more like poetics than the form of verification required by the cognitive genre (the sort required by the tribunal). Chapter Four, then, picks up two variants of dialectics: Hegel’s (speculative dialectics) and then Adorno’s (negative dialectics). In brief, consider Hegel’s to be a three step argumentative form wherein a thesis (A is X) is countered by an antithesis (A is Y), and initiates their mediation in order to establish a synthesis (A is Z, which harmonizes an answer that incorporates aspects of X and Y), which can then become a new thesis, and the cycle goes on. In contrast, Adorno’s argumentative form amplifies the ‘work of the negative’ (i.e., all dialectics make progress by the negative, by the conflict of X’s and Y’s) so as to keep the argument moving without accepting any positivity (so, the synthesis is never an affirmative ‘A is Z’, but always an ‘A is neither X or Y, so … let’s find the Q, R, S, and T that it is also not’). The purpose of exploring dialectics again is because it is so successful, despite the fact it fails (per ideas in Plato Notice); so, Lyotard tries out these two types of dialectics to see if they can be more successful. Hegel’s model is shown to lead to dire consequences, despite its power to move argument on and better address differends; Adorno’s model is shown to avoid many of the pitfalls of Hegel’s, however, it also ultimately fails because it keeps the argument going, but prohibits it from ever actually getting to a solution that would allow us to undo differends. Showing how dialectics keep argument going reveals them to be formative of “narratives.” Narratives are the strongest way to ‘deal with’ differends, albeit, not solve them. These are utterly important, then, to explore because they can cause differends as well as being able to cover them over. Seeing them as narratives reveals a lot of important insights into how the differend between the survivor and revisionist happens, and how such conditions will keep happening even if we shoot down one revisionist after another, hence underscores the importance of doing this work Lyotard is doing. Some of the key insights we learn are ...

Outline:

So, Chapter Two (“Referent, Name”) explores what is indicated by the ontological: the referent (that about which a phrase is referring) and the name (a denomination of the referent). In this chapter, we see the many failures in the attempt to verify ontological phrases through linkages with phrases from other genres of discourse; despite all these failures, it ends with the introduction of how the ‘phrase event’ leaves us with a “complex feeling” about that which we have failed to validate.

Chapter Three (“Presentation”), following Two’s succession of failures, begins all over again from One’s problem, like a reset, and explores a different way to verify what we haven’t been able to about the ‘phrase event.’ Instead of trying out a new genre of discourse to express it, it (1) reconsiders how the ‘phrase event’ happens (that the ‘presentation of a phrase’ is an ‘event’ that happens that then requires its ‘situation’); then, (2) realizes that the ontological designations only occur in that subsequent situation; thus, (3) explores if the ‘happening’s happening’ (the eventing of the event or presenting of the presentation) can prove a certain foundation (every event happens TO a subject), and thereby validate the ontological status of the witness; however, (4) discovers how this fails (because the subject does not pre-exist before the event); and therefore (5) establishes how the first two steps (a) involve questions on time because of the before/after of ‘happening’ and ‘situation,’ and how, because of the third step, (b) one must ‘situate’ the happening through linkages, and thus, (c) because the presentation of the phrase is a nebulous event prior to ‘situation,’ and no one situation will capture its entirety, ‘feeling’ needs to lead our attempts at its expression.

Chapter Four (“Result”), like Three, doesn’t exactly pick up from where the previous chapter left off; unlike Three, though, it is not exactly a reset, but a circling around to readdress a dismissed attempt to express what has been silenced: dialectics. In Chapter One’s “Plato Notice,” Socratic dialectics or his style of argument in dialogue was suggested to fail this expression because (in part) it relied upon seduction, persuasion, something more like poetics than the form of verification required by the cognitive genre (the sort required by the tribunal). Chapter Four, then, picks up two variants of dialectics: Hegel’s (speculative dialectics) and then Adorno’s (negative dialectics). In brief, consider Hegel’s to be a three step argumentative form wherein a thesis (A is X) is countered by an antithesis (A is Y), and initiates their mediation in order to establish a synthesis (A is Z, which harmonizes an answer that incorporates aspects of X and Y), which can then become a new thesis, and the cycle goes on. In contrast, Adorno’s argumentative form amplifies the ‘work of the negative’ (i.e., all dialectics make progress by the negative, by the conflict of X’s and Y’s) so as to keep the argument moving without accepting any positivity (so, the synthesis is never an affirmative ‘A is Z’, but always an ‘A is neither X or Y, so … let’s find the Q, R, S, and T that it is also not’). The purpose of exploring dialectics again is because it is so successful, despite the fact it fails (per ideas in Plato Notice); so, Lyotard tries out these two types of dialectics to see if they can be more successful. Hegel’s model is shown to lead to dire consequences, despite its power to move argument on and better address differends; Adorno’s model is shown to avoid many of the pitfalls of Hegel’s, however, it also ultimately fails because it keeps the argument going, but prohibits it from ever actually getting to a solution that would allow us to undo differends. Showing how dialectics keep argument going reveals them to be formative of “narratives.” Narratives are the strongest way to ‘deal with’ differends, albeit, not solve them. These are utterly important, then, to explore because they can cause differends as well as being able to cover them over. Seeing them as narratives reveals a lot of important insights into how the differend between the survivor and revisionist happens, and how such conditions will keep happening even if we shoot down one revisionist after another, hence underscores the importance of doing this work Lyotard is doing. Some of the key insights we learn are ...

Outline:

(II) Lyotard's The Differend, Ch.4: "RESULT"

§152-53: (Hegel’s) (Speculative) Dialectics vs. (Adorno’s) Negative Dialectics

* (Hegel’s) (Speculative) Dialectics: this dialectics has no true discussions

- i.e., envision this as thesis meeting antithesis, mediation happening, creation of synthesis, and repeat wherein the synthesis becomes a new antithesis … in this spiral, Lyotard argues that the thesis-antithesis collision is no true discussion (there are no genuine objections brought forth) because they are in service to ‘sublation,’ the work of mediation wherein synthesis is forged.

* But our project necessitates discussion: there is a phrase and we must link … hence, Lyotard explores Adorno’s negative dialectics to see it if is better …

* (Adorno’s) Negative Dialectics: this dialectics allows more productivity in our project, but will ultimately fail to solve the problem because it refuses us anything but silence

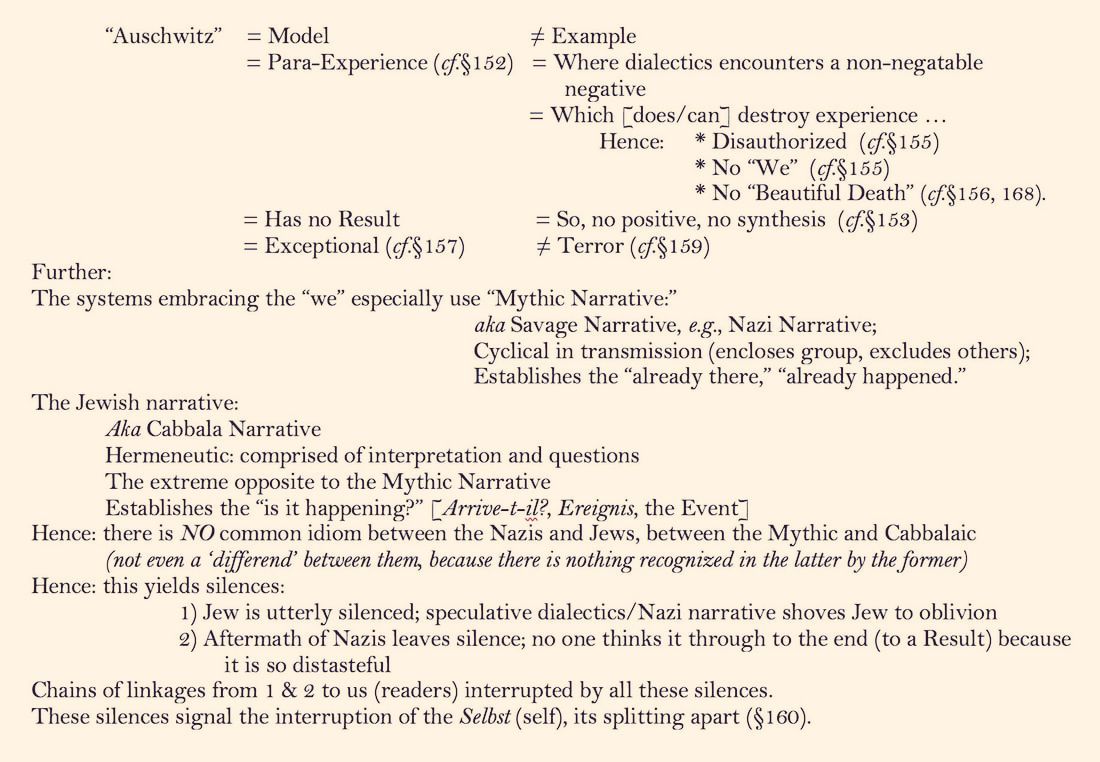

- i.e., §152: the main difference from Hegel’s dialectic is that Adorno refuses ‘positivity’ (true synthesis) to come from the work of the ‘negative’ (the force of mediation). This is beneficial because it permits us the idea of ‘hope’ (because a synthesis doesn’t just move us beyond questions), illuminates ‘micrologies’ (allows us to look at specimens instead of generalized concepts), which leads us to identify the issue be about the Proper Name (“Auschwitz”), and shows how ‘models’ are not ‘examples’ (“Auschwitz” as a model is not just one more example of injustice or genocide, etc., hence, keeps us from blurring all cases together), which shows us that “Auschwitz” names a “para-experience, where dialectics would encounter a non-negatable negative” (§152; i.e., it is exceptional, a ‘true’ differend is encountered here, and it will have the power to crack the speculative genre).

- §153: As ‘experience,’ the speculative genre can transcend so as to convert negative into being; as ‘para-experience,’ “Auschwitz” cannot because it has no ‘result’—but, this forbids us to speak, to link … so, Lyotard asks: is there some other type of phrase possible?

- §154: Lyotard shows why Hegel deserves the critique of Adorno (affirms the power of the negative, but then backtracks to still affirm positive), and explains ‘Result’ for the positive (it is determined content), and for the skeptical (result makes the nothing into a determinate in the form of the negation of specific determinations). This ‘skeptical result’ gives us a half way between Hegel and Adorno, which Lyotard will pursue.

§155: WE:

“After ‘Auschwitz’” lacks a result because it lacks determination; it lacks determination because it is the name of a ‘para-experience’ that is the destruction of experience; in destroying experience, the possibility of a “we” is eliminated. This requires exploration of:

- Deauthorization & Authorization:

- In authorization, “we the people” permits substitution (any I can be this we); but, this operates on two heterogeneities:

- Heterogeneity of the pronoun: ‘we’ who decree is not ‘we’ who obey.

- Heterogeneity of the phrase: the normative phrase that acts as a performative effectuates the legitimation; BUT the prescriptive phrase does not, it requires another phrase linked to it to effectuate any legitimacy.

- In authorization, “we the people” permits substitution (any I can be this we); but, this operates on two heterogeneities:

§156: Beautiful Death:

Can the decreed obligation “die” be authorized? Yes: One may order me to die, and I take on this phrase as its own addressor (order myself to die) IF it is modalized into a “die because” that presents a choice between alternatives. In these cases, an even tighter bond is formed between the ‘we.’

§157: Exception:

“Auschwitz” names the forbiddance of the “beautiful death” (self-authorized).

This means it is an “Exception” (it is a model, not an example).

This cracks the ability for speculative reason (Hegel’s dialectics) to synthesize the ‘we’ of nazi with the ‘we’ of Jews; there is nothing but the former’s obliteration of the name of the latter (no mediation, no preservation of antithesis into synthesis).

§158: Third Party?

Speculative reason tries again to be able to grapple with this … but in order for the speculative to synthesize anything, it would require a third party outside of the nazi-Jew (non-)relation; this third party could never mediate their dispute, the best it could do is report about it to a fourth party (we who read about it).

§159: Without a Result:

Terror is inclusive: all must recognize it for it to be effective.

“Auschwitz” is not terror; it is an exception; the Nazis require no recognition from Jews.

§160: Return:

Mythic Narrative (c.f., funeral oration in Plato Notice, p.20): this form of discourse encircles those chosen within and allows/necessitates slippage of names (all named within the system); this is the genre the Nazis use, too.

Cabbala ‘narrative’: this is the Jewish other-extreme from the above; it operates within the “is it happening?” (the event); its phrase is obliterated by the mythic. Only silence left.

(III) Lyotard's The Differend, Ch.5: "OBLIGATION"

Review / Overview:

The end of Chapter Four (“Result”) revealed how vast the abyss and great the heteronomy between the narratives used by the Nazis (repurposing the mythic narrative) and Jews (using the hermeneutic or ‘Cabbala narrative form’) resulted in not a conflict that could be fought out, but an utter silencing. This silencing works on two levels: first, within “Auschwitz” the Jew is utterly silenced because speculative dialectics stuck in Nazi narrative shoves the Jew to oblivion; second, “After Auschwitz,” so, in the aftermath of the Nazis, silence persists because no one thinks the event of the first level through to the end (to a Result), in part, it may be because thinking the totality of it is impossible, and in part because it is so distasteful. So all of the chains of linkages from this first level to the second and then to us (readers, all in history afterwards) are interrupted by all these silences. Lyotard says that these silences signal the interruption of the Selbst (self), its splitting apart (§160). If this is the case, this is an obstacle more severe than all the failures we have seen through the first four chapters.

So, Chapter Five (“Obligation”) reveals the ‘interlocutor’ (Lyotard, us, anyone thinking though this) fighting really hard to find a way to grasp the silencing and use silence as a way to prompt an address to the problem. Hence, its first two sections (§161-62) explore how the split self could expose injustice, destroy presumptuousness and how we could ask if the speculative non-sense of “Auschwitz” (i.e., how “Auschwitz” does not validate sense (meaning) by the rules of that genre of language) could conceal a ‘Paradox of Faith.’ This question invokes Søren Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, which analyzes the case of Abraham’s command by God to sacrifice his son Isaac to show the incommensurability between reason and faith (the former being validation acceptable in a court and the latter being a validation acceptable by the religious). Lyotard works through this chapter to show how the stance of faith is “obligation” and this is not “obedience” (the key: in the latter, one questions ‘why?’, deliberates, decides; in the former, there are none of these, instead, just automatic action). This stance of faith’s obligation is then identified as “the ethical genre of discourse;” this genre gives the addressee a non-thinkable certainty (one feels it), and such is utterly private; it cannot be experientially shared and cannot explained in a way that others would accept (it cannot be translated into phrases verifiable by the cognitive or tribunal’s rules, e.g., according to religion, Abraham was willing to sacrifice Isaac; according to the court, Abraham was willing to murder Isaac). So, according to the court, to the ‘obedience’ stance, which will be linked to the political (rule by laws), “obligation should be described as a scandal” (§170). While the ‘interlocutor’ still tries to make the faith stance valid (§§171-73), Lyotard shows how the cognitive genre (tribunal) won’t accept it (§§174-77), but, then moves into the closing Kant 2 Notice, which shifts us into the political genre, to show how Kant’s philosophy offers legitimation that only needs an “as if” foundation for its justification. This “as if” foundation reveals the abyss between the genres of discourse, but it also offers us a way to forge a “passage” between them in order to guide the construction of a community (of the political, the polis, the people).

§161-62:

The split self could expose injustice, destroy presumptuousness … But … we could ask if the speculative non-sense of “Auschwitz” could conceal a ‘Paradox of Faith’ …? This is to invoke Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, the case of Abraham and Isaac, and the issue of the incommensurability between reason and faith (a court and the religious).

§163:

This is not an issue of obedience, but of Obligation (to the call). Connection to Prescription.

§164:

Interlocutor: cases are different! Lyotard: their sameness is in the role/position of authority (cf. §155) and that the request is taken as law.

§165:

Obligation: a phrase is obligated if the addressee is obligated. Obligation ≠ “Why?”

“Why” is not the obligation genre. “I’s” Blindness: obligation is not explanation (“why?”)

§166:

Blindness: description ≠ prescription; “is” ≠ “ought”

Abraham: there is no cognitive here, no totality graspable.

§167:

Angels blind (challenge God, why give water to who will betray you)

God neither has grasp of totality in His justness.

§168:

“Holocaust” from the Greek holokauston, from the Hebrew olah, meaning “completely burnt offering,” a “sacrifice to God” … hence, implies an underlying guilt in the victims. The name implies a serious of specious questions that are, nevertheless, not falsifiable (cf. “beautiful death,” §156), but they are also not legitimate (i.e., they do not legitimate or authorize what happened, cf. §155).

§169:

Blindness: put the “I” in the place of the other, neutralization of the other’s transcendence; anything from this yields cognitive and is a crime against ethics.

§170:

Obligation as Scandal: –but this makes it a psychoanalytic and/or phenomenological, of a dispossessed or cloven consciousness (cf., §160: split self). The split presupposes totality, result.

The split self could expose injustice, destroy presumptuousness … But … we could ask if the speculative non-sense of “Auschwitz” could conceal a ‘Paradox of Faith’ …? This is to invoke Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, the case of Abraham and Isaac, and the issue of the incommensurability between reason and faith (a court and the religious).

§163:

This is not an issue of obedience, but of Obligation (to the call). Connection to Prescription.

§164:

Interlocutor: cases are different! Lyotard: their sameness is in the role/position of authority (cf. §155) and that the request is taken as law.

§165:

Obligation: a phrase is obligated if the addressee is obligated. Obligation ≠ “Why?”

“Why” is not the obligation genre. “I’s” Blindness: obligation is not explanation (“why?”)

§166:

Blindness: description ≠ prescription; “is” ≠ “ought”

Abraham: there is no cognitive here, no totality graspable.

§167:

Angels blind (challenge God, why give water to who will betray you)

God neither has grasp of totality in His justness.

§168:

“Holocaust” from the Greek holokauston, from the Hebrew olah, meaning “completely burnt offering,” a “sacrifice to God” … hence, implies an underlying guilt in the victims. The name implies a serious of specious questions that are, nevertheless, not falsifiable (cf. “beautiful death,” §156), but they are also not legitimate (i.e., they do not legitimate or authorize what happened, cf. §155).

§169:

Blindness: put the “I” in the place of the other, neutralization of the other’s transcendence; anything from this yields cognitive and is a crime against ethics.

§170:

Obligation as Scandal: –but this makes it a psychoanalytic and/or phenomenological, of a dispossessed or cloven consciousness (cf., §160: split self). The split presupposes totality, result.

Levinas Notice (and §171):

Levinas’ Marvel (§171): the other as other (i.e., not other from self or self from other (p.110)).

- Levinas’ ethics begin from his radical rethinking of the canon’s insistence on ‘recognition;’

- (e.g., for Hegel, one only becomes self-conscious (hence, not mere conscious being, but a fully self-conscious being, a ‘human’) by confronting an other who is not ‘I;’ in the confrontation, after a stage of mirroring that is like a figuring out that ‘it’ is ‘not me,’ a “life or death struggle” ensues, both place an ideal (‘recognize me as me!’) over physical survival, and one steps down (becomes “bondsman”) and one wins (becomes “lord/master”), and the dialectic continues.

- e.g., for Husserl, he proposes that the self comes to know others through a phenomenological process where one first ‘reduces’ the world down to one’s ‘sphere of ownness’ (what is most genuinely me?), and then engages an ‘analogical apperception’ (apperception is one’s consciousness of one’s self, and then the self makes this an analogy for what it must be like for others to be themselves), hence, to ‘know others’ is kind of like using empathy (I know what it is like for me to be me, so, by analogy, you must know yourself in a similar way, hence, I can know you as someone who is not-me but like me).)

- For Levinas, he rejects knowing the other as of-me, from-me, or like-me. Instead, he posits that the other is wholly other, hence he calls the other a “marvel.”

- This means that the encounter with the other (a first step to any sort of “knowing” of the other) doesn’t begin by thinking sameness, identity, or likeness/analogy. Instead: “The other can only befall the ego, like a revelation, through a break-in” (p.110). To encounter the other is a horrific shock. To describe this, he uses language like “violence,” and that the horrifying appearance of the other takes the self “hostage.” Hence, encountering the other is not cognitive; we think nothing, know nothing, deduce nothing, etc.; we “experience” this only by a feeling (like the “complex feeling” of §93, etc., it is a feeling of the impossible); this event/feeling invokes immediate obligation (we do not reason through whether we should obey, instead, it is immediate (no mediating thought) obligation—this is “The Ethical Genre of Discourse.”

- Ethical Genre: prohibits discourse (obligation ≠ “why”)

- Obligation presupposes liability: we are liable for the other (and there is no “because,” just immediate surety felt as to this responsibility and accountability to and before the other).

- Obligation’s presupposition of liability also implies: there is a fracture in the ego’s fortress (i.e., the absolute otherness of the self from all others also inherently has a crack that makes it open to being cracked open by the appearance of the other).

- For Levinas, this is the whole of Ethics (i.e., not an origin or aspect, but the whole entirety of what it is); another way to say this is that this means Ethics is entirely: freedom and persecution.

- Arrival of the other suppresses the “I” as a subject of experience (i.e., this break-in by the other and consequent immediate obligation to the other wholly depletes the self of subjectivity, of the experience of being a self, because it cuts off any possibility of reason; one does not think or explain, one simply is obligated).

- (If we draw out the conclusions we see the inherent paradox: this account of ethics places obligation outside of the bounds of deliberation, decision, intentional action, freedom to choose/will, etc.; if this is what ethics is, how does ethical judgment justly judge when action is not voluntarily chosen?)

Gnostics’ Alien-ness (§171):

- The gnostics are the mystics; mystical “experience” is immediate, direct, intuitive knowledge of God or ultimate reality attained through personal religious experience, which may be as a complete return back to The One or one’s origin or via a single or series of brief encounters, dreams, or visions wherein their continuum of contact is proportionate to their yielded received knowledge (i.e., complete divine union can yield indubitable “knowledge” to the briefest mystical event yielding scant or veiled insight).

- Lyotard’s point here is that in the mystical experience/divine union is the whole loss of one’s own ego (the self is escaped or given up or destroyed in the act of one uniting with The One). This, he says, citing another scholar, gives the sense of Umheimlichkeit, literally, the not-at-home-ness (cf., §218 on heim … this topic reappears importantly later in book), more commonly translated as the “Uncanny.” (This was a prevailing theme/feeling analyzed by Heidegger’s Being and Time, which launched existentialism, and also deeply studied by Freud and subsequent psychoanalysts).

|

To Continue on Chapters Six & Seven ... select the button, right:

|

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by MacHighway