Lars von Trier & Thomas Vinterberg’s “Dogma 95 Manifesto”

(Read a copy: ~here~)

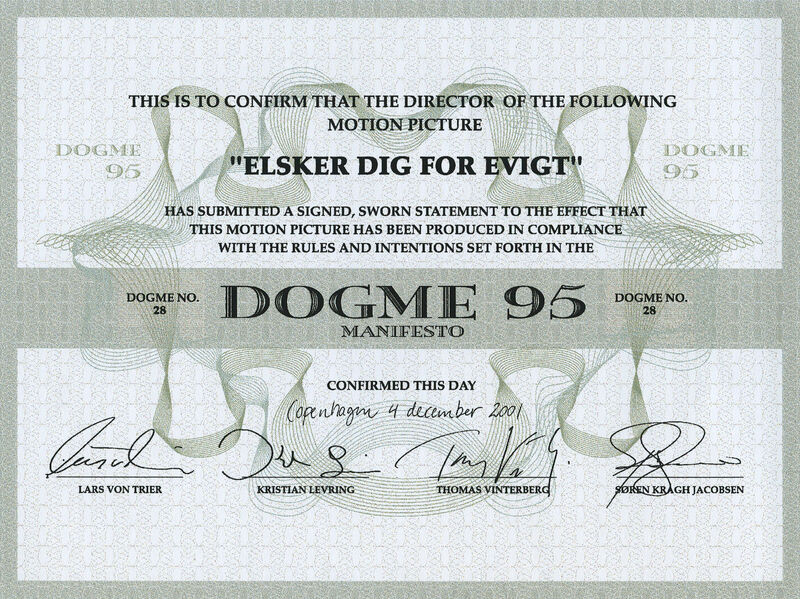

Dogma 95: a “collection of film directors founded in Copenhagen in spring 1995” (all quotes from the Manifesto at the above web address unless noted) and the style of filming that followed from their creation of the school, sometimes called the Dogma 95 Collective. The principle directors founding the school included the Danish Lars von Trier, Thomas Vinterberg, Kristian Levring, and Søren Kragh-Jacobsen. The manifesto was initiated (via printed red pamphlets) by von Trier at a 1995 Parisian conference (Le cinema vers son deusième siècle) that was reconsidering the first 100 years of film and explore what the future held for cinema. They started as a reaction to ‘contemporary tendencies in [New Wave*] film,’ conceiving themselves as undertaking “a rescue action!” (Although, they purposefully mimic the wording of François Truffaut’s “Une certaine tendance du cinema français,” a New Wave manifesto of 1954.) Thus, they claim, the first reactionary move was made in 1960’s New Wave movement, but the Dogma 95 group deemed that movement as having the right goal, but accomplishing it by the wrong means (“The new wave proved to be a ripple that washed ashore and turned to muck.”)

Dogma 95: a “collection of film directors founded in Copenhagen in spring 1995” (all quotes from the Manifesto at the above web address unless noted) and the style of filming that followed from their creation of the school, sometimes called the Dogma 95 Collective. The principle directors founding the school included the Danish Lars von Trier, Thomas Vinterberg, Kristian Levring, and Søren Kragh-Jacobsen. The manifesto was initiated (via printed red pamphlets) by von Trier at a 1995 Parisian conference (Le cinema vers son deusième siècle) that was reconsidering the first 100 years of film and explore what the future held for cinema. They started as a reaction to ‘contemporary tendencies in [New Wave*] film,’ conceiving themselves as undertaking “a rescue action!” (Although, they purposefully mimic the wording of François Truffaut’s “Une certaine tendance du cinema français,” a New Wave manifesto of 1954.) Thus, they claim, the first reactionary move was made in 1960’s New Wave movement, but the Dogma 95 group deemed that movement as having the right goal, but accomplishing it by the wrong means (“The new wave proved to be a ripple that washed ashore and turned to muck.”)

- * French New Wave Film: these filmmakers grew up with limited selections of film in 1940’s occupied France; the censors banned all American films, leaving only light German and a handful of French pictures. After liberation, the film industry exploded in France, accompanied by numerous film clubs and journals dedicated to film theory. The young filmmakers involved in this explosion became the leading figures of French New Wave, notably François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Alain Resnais, Jacques Rivette, Claude Chabrol, Roger Vadim, Pierre Kast, and a few older filmmakers like Eric Rohmer and Andre Bazin (also René Clement and Marcel Carne) and aestheticians like Alexandre Astruc. The leading characteristics of New Wave are an intense disdain for mainstream cinema’s tradition of adapting very ‘safe’ literary works, using old-fashioned studio filming techniques, and sticking too close to screenplays and not freely adapting and improvising. An influx of money into the film industry led to developments in new cameras, which were lighter and handheld, required less light and worked with portable sound equipment, hence, filmmaking could go out into the streets; despite the influx of money, this led to budget filmmaking since the equipment was cheaper to procure, thus opening doors to less professional filmmakers and great experimentation. Most New Waves films are labeled “passionate and irreverent.” The passion of these filmmakers helped ignite the French riots of 1968 (which were as aesthetically motived as they were political)—many of these beginning in the cinema clubs, especially the most famous, the Cinématheque Francaise, whose leader was fired by the Minister of Culture, sparking a riot and sustained protests in the streets that turned violent. Mayhem at the Cannes film festival (from French and international directors) eventually led to the reinstatement of the head of the Cinématheque and cessation of the riots.

The principle objective for Dogma 95 was to simplify and purify filmmaking, which practically meant the elimination of artificially created effects and typical post-production modifications. The aim was to more fully engage the audience in the film, redirecting their attention to the internal atmosphere of the work and narrative.

Despite the ideals of freedom to which the movement held, their critique of the New Wave was a perceived lack of unifying focus and shared commitments: “The wave was up for grabs, like the directors themselves.” Given this lack of unity and unified vision, Dogma 95 accused the New Wave of beginning as anti-bourgeois and yet succumbing to the bourgeoisie (i.e., they fell prey to what they had been fighting against) because their starting place was rooted within “the bourgeois perception of art.”

Fighting this error, Dogma 95 commands itself to be “not individual!” This is seen practically in various aspects like a lack of credit given to the directors and titles that were mere numbers, rather than meaningful descriptors (although, the number of times these were adhered to is limited).

In a claim remarkably similar to ideas heard in Benjamin, Adorno, and Marcuse, the Manifesto proclaims: “Today a technological storm is raging, the result of which will be the ultimate democratization of the cinema. For the first time, anyone can make movies. But the more accessible the medium becomes, the more important the avant-garde.” Like the Critical Theorists, we hear the desire for democratization along with the warning of how it may become merely populist (“cosmeticized to death”) and lack any rigor and originality. Hence, Dogma 95 calls for discipline—the strict, militant adherence to set avant-garde rules.

The rules against the over-individualism of film (which leads to bourgeois cinema wherein the directors only try to “fool the audience” and yields “barren” films that are each an “illusion of pathos and an illusion of love”) are complied in their “Vow of Chastity.” By the rules of this vow, Dogma 95 wishes to counter “the film of illusion” in which decadent filmmakers use technology to eliminate raw truth.

The Vow of Chastity (in essence):

Most interestingly is what follows the delineation of commands:

This is a rather dramatic departure from any Kantian idea of the genius of the work of art as it is a departure from Tolstoy’s personal communication of the artist’s emotions to the spectator. It is equally a departure from Benjamin’s idea of the aura of a work of art and the Futurists’ embrace of the whole atmosphere.

In 2002, the Dogma 95 Collective declared their manifesto to have become a genre formula against all their best intentions, and officially pronounced its death. What the movement caused, however, was a strong legitimization of “low-budget” filmmaking that reinvigorated the excitement of early experimentation in film through what could be described as “guerrilla-style” filmmaking.

- (1) shoot on location without brought-in props and sets;

- (2) sound must be natural to the scenes shot (i.e., not dubbed in after);

- (3) only hand-held cameras;

- (4) color film only without artificial lighting;

- (5) filters or optic tricks not permitted;

- (6) no superficial action;

- (7) film must embrace the here and now (no time/space alienation);

- (8) no genre movies;

- (9) must use 35 mm film;

- (10) the director cannot be credited.

Most interestingly is what follows the delineation of commands:

- “I swear as a director to refrain from personal taste! I am no longer an artist. I swear from creating a ‘work,’ as I regard the instant as more important than the whole. My supreme goal is to force the truth out of my characters and settings.”

This is a rather dramatic departure from any Kantian idea of the genius of the work of art as it is a departure from Tolstoy’s personal communication of the artist’s emotions to the spectator. It is equally a departure from Benjamin’s idea of the aura of a work of art and the Futurists’ embrace of the whole atmosphere.

In 2002, the Dogma 95 Collective declared their manifesto to have become a genre formula against all their best intentions, and officially pronounced its death. What the movement caused, however, was a strong legitimization of “low-budget” filmmaking that reinvigorated the excitement of early experimentation in film through what could be described as “guerrilla-style” filmmaking.

Links to Outside Readings (hover over the seemingly blank spots to find clickable links):

(Click ~here~ to read an article by Patrick Kingsley, “How the Dogme manifesto reinvented Denmark”)

(Click ~here~ for a list of ten Dogme 95 Films)

(Click ~here~ for a list of 20 Dogme 95 Films)

(Click ~here~ for a link to Film-Philosophy Journal, with open-access articles)

Some examples of (more or less) Dogma 95 films (and those inspired by it):

Please be advised: many of the films are very explicit and emotionally troubling; anyone with sensitivities to brutally frank adult content should carefully read about the films before viewing.

Lars von Trier: Europa (1991); Breaking the Waves (1996); The Idiots (1998) [called Dogma 2]; Dancer in the Dark (2000); Dogville (2003); Manderlay (2005); Melancholia (2011)

Thomas Vinterberg: The Celebration (1998) [called Dogma 1]

Søren Kragh-Jacobsen: Mifune’s Last Song (1999) [called Dogma 3]

Kristian Levring: The King is Alive (2000)

Jean-Marc Barr: Lovers (1999)

Lone Scherfig: Italian for Beginners (2001)

Susanne Bier: Open Hearts (2002)

Harmony Korine: Julien Donkey-Boy (1999)

(Click ~here~ to read an article by Patrick Kingsley, “How the Dogme manifesto reinvented Denmark”)

(Click ~here~ for a list of ten Dogme 95 Films)

(Click ~here~ for a list of 20 Dogme 95 Films)

(Click ~here~ for a link to Film-Philosophy Journal, with open-access articles)

Some examples of (more or less) Dogma 95 films (and those inspired by it):

Please be advised: many of the films are very explicit and emotionally troubling; anyone with sensitivities to brutally frank adult content should carefully read about the films before viewing.

Lars von Trier: Europa (1991); Breaking the Waves (1996); The Idiots (1998) [called Dogma 2]; Dancer in the Dark (2000); Dogville (2003); Manderlay (2005); Melancholia (2011)

Thomas Vinterberg: The Celebration (1998) [called Dogma 1]

Søren Kragh-Jacobsen: Mifune’s Last Song (1999) [called Dogma 3]

Kristian Levring: The King is Alive (2000)

Jean-Marc Barr: Lovers (1999)

Lone Scherfig: Italian for Beginners (2001)

Susanne Bier: Open Hearts (2002)

Harmony Korine: Julien Donkey-Boy (1999)

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by MacHighway