Heidegger's Being and Time

Division One, Chapters One and Two

{Part I:--later editions cut out this designation as 'part one' is the only part finished}

The Interpretation of Dasein in Terms of Temporality and the Explication of Time

as the Transcendental Horizon of the Question of Being

Division One:

The Preparatory Fundamental Analysis of Dasein

The Interpretation of Dasein in Terms of Temporality and the Explication of Time

as the Transcendental Horizon of the Question of Being

Division One:

The Preparatory Fundamental Analysis of Dasein

- Chapter One: will offer an exposition of the existential analysis of Dasein and delimitation of that from parallel investigations.

- Chapter Two: will offer an analysis of the fundamental structure of Dasein: being-in-the-world (which is the “a priori” of Dasein, and is a primordially whole and complete structure).

- Chapter Three: will analyze the worldliness of the world.

- Chapter Four: will offer a study of being-in-the-world as being a self and being with others.

- Chapter Five: will look into being-in as such.

- And Chapter Six: will then offer the whole picture, a preliminary demonstration of the being of Dasein wherein its existential meaning is care (H.p.41).

Chapter One:

The Exposition of the Task of a Preparatory Analysis of Da-sein:

§9

Da-sein is: the focus of our phenomenological-ontological analysis; is always the “I” itself; has the being that is mine; Da-sein’s being is related to its Being, entrusted to its Being; it is the being who is concerned about its own Being. Heidegger then discerns two fundamental points that follow from this:

(1) {existentia over essentia} “The ‘essence’ of this being lies in its to be” (H.p.42)--it helps to read the “to be” as the translation of “Sein,” wherein instead of translating it as “Being,” we transliterate as “to be” to suggest that we are interested in the meaning of its being, that dynamic meaning, not substance.

Da-sein’s “whatness,” its objective presence (Vorhandenheit), its “essence,” its “essentia” must be understood in terms of its being (existentia). That is, we can only understand what Da-sein IS (its essence) by seeking to understand its existence, its existing (as itself). “The ‘essence’ of Da-sein lies in its existence” (H.p.42).

(2) {always-being-mine} “The being which this being is concerned about in its being always my own” (H.p.42).

“Thus, Da-sein is never to be understood ontologically as a case and instance of a genus of beings as objectively present” (H.p.42). Remember this idea from the three prejudices in the Introduction I: Being is not a genus. So, this is not the Being as the highest category of distinction of which all those other things are species of it. Discussions of Da-sein should use the personal pronouns (e.g., I am, you are, we are, etc.). This follows from (1), above, because to understand the essence, we must understand existence.

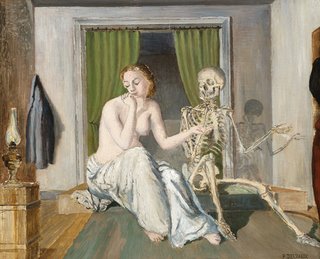

Da-sein is my own. “The being which is concerned in its being about its being is related to its being as its truest possibility. Da-sein is always its possibility. It does not ‘have’ that possibility only as a mere attribute of something objectively present. And because Da-sein is always its possibility, it can ‘choose’ itself in its being, it can win itself, it can lose itself, or it can never and only ‘apparently’ win itself. It can only have lost itself and it can only have not yet gained itself because it is essentially possible as authentic, that is, it belongs to itself” (H.pp.42-3).

To embrace the existence (rather than starting with some essence), we embrace the dynamic possibility of Da-sein, of the being that is my own, in its full range of possibility. Possibilities are not attributes of a thing--e.g., that being could have brown hair or bad genes or good teeth—instead, they are Da-sein. All Da-sein is possible of choosing its way of being itself, authentically or inauthentically.

Now … in addition to always choosing itself … Da-sein also already, somehow, understands itself (H.p.43). In the same way one might say you live in your own skin, so even if you haven’t thought really long and hard about what you mean, you do, by the fact of being you, have some degree of self-understanding.

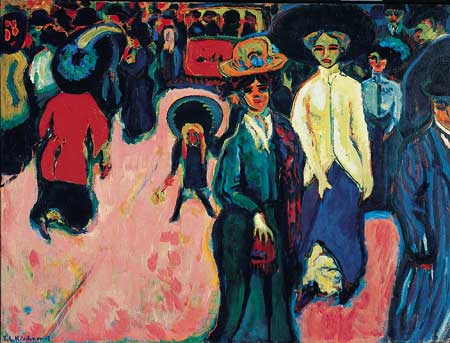

Now, just because Da-sein has the character of being mine, and is studied in its existence, not essence, and because there is a natural understanding of it … this does not mean that Da-sein is Billy or Suzy or Zelda or Hans: “… this cannot mean that Da-sein is to be construed in terms of a concrete possible idea of existence” (H.p.43). Studied concretely, yes—in the sense of phenomenologically embedded in existence; but, not as a particular human being. Instead of differentiating one being to be Da-sein, we begin by looking indifferently … maybe a better way to say this is by saying we study a generic being who questions his or her own being. This is Heidegger’s “indifference of the everydayness of Da-sein,” the “averageness” of Da-sein (H.p.43).

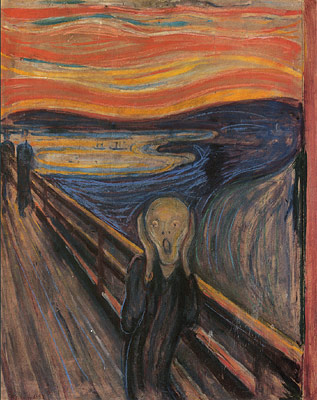

We begin in this ontic everydayness …which Heidegger reemphasizes through quoting Augustine (“But what is closer to me than myself?”) and underscores the intensely anxious Saint’s response (“Assuredly I labor here and I labor within myself: I have become to myself a land of trouble and inordinate sweat”) (H.pp.43-4). This everydayness is the “a priori” of our study … it is not just a mere aspect of Da-sein, but the fundamental is-ness of it to which it always relates, either by embracing or fleeing.

Now, Heidegger turns again to the differentiation of studying the ‘whatness’ (Vorhandenheit, the objective presence, the substance ontology he wants to depart from) versus the ‘thatness’ or ‘who’ (the existentials, the ontic-ontological phenomenological approach):

First, there is the easy distinction:

He includes here the interesting etymological cruise through “categories” (think in terms of Aristotle and Kant) understood more ontologically:

In this quote, Heidegger is not referring us back to the Introduction’s discussion of legein and logos … instead, he is meaning that right here, now, in the world, when we undertake discussions with being, we have already presented ourselves. We have given ourselves as a ‘what’/‘who’ and demanded a revelation of their ‘what’/‘who’ … we can use “what” so long as we understand that this seemingly objective presentation isn’t so objective, but showing that conceals. Hence, our address of another is a self-showing of ourselves that asks the other to self-show him/herself. This address is a serious demand because the self-showing we ask for is as it/she/he is in itself already, always, and for all. A stunning passage … but Heidegger doesn’t help clarify that this sense is different from the sort of category used in substance ontology, in that type of study of being that he wants to get over and away from. He immediately then switches back to show how ‘what’ and ‘categories’ refer to the objective presence that we, beings, can be, but only when considered as things. (In the next chapter, we will see Heidegger working to rid us of any simple subject-object dichotomy, hence, I use this idea of ‘thingliness’ here carefully.)

§10

Heidegger then moves to differentiate the analytic of Da-sein from the sciences of anthropology, psychology, and biology. Essentially, none of these fields understand Da-sein at all. They chop up aspects and never ask the fundamental questions. Heidegger underlines this by again critiquing Descartes for not asking about the “sum,” about being, when naming us as the “thing that thinks” (H.pp.45-6). He also accuses us of dragging along this sort of unquestioned presumptions “no matter how energetic one’s ontic protestations against the ‘substantial soul’ or the ‘reification of consciousness’” (H.p.46) … is he cracking a joke here? Can’t we see the poor philosopher he disdains so much waving about his arms saying no, no, no, there is no ‘soul,’ even as his thesis has presumed the same exact structure, just now has called it ‘geist’ or ‘flux’ or what have you?

Then, while psychology gets is just as wrong as anthropology and biology, Heidegger is complementary of Scheler and Husserl’s attempt to move away from psychology and, instead, adopt a notion of the person or psyche as the “immediately co-experienced unity of ex-periencing” (H.p.47), or, easier said, as neither a thing, nor a substance, nor even an object. However, even this does not go as far as Heidegger himself will go with his radical notion of Da-sein.

Anthropology’s biggest problems are two: interpreting the human as the rational animal or as the theological one (H.pp.48-9). To do either of these is to fall prey to the prejudices against being raised in the Introduction I.

Biology goes wrong because it reduces the study to “life.” Surely, life has a kind of being, but we can only access what this is through the fundamental analytic of Da-sein. And, life is neither Da-sein itself, nor some simple attribute of Da-sein (H.p.50).

§11

Now, returning to anthropological sort of concerns, Heidegger needs to clarify that his average everydayness is fundamental, natural, and simple, but certainly not the same as “primitive” in the sense of ancient cave people, etc.: “Everydayness is not the same thing as primitiveness” (H.p.50). So, when we uncover these essential structures of Da-sein, we are not going to be dealing with some pre-evolutionary traits, instincts, etc.

Heidegger then ends the section and chapter remarking on the “world,” which is of utmost importance to understand in order to understand Da-sein. “World” itself will be constitutive of Da-sein, it is what makes Da-sein who Da-sein is, and it is what will reveal the structures. This world is not made clearer at all by simply laying out a bunch of information (geographical, statistical, poetic, or otherwise).

The Exposition of the Task of a Preparatory Analysis of Da-sein:

§9

Da-sein is: the focus of our phenomenological-ontological analysis; is always the “I” itself; has the being that is mine; Da-sein’s being is related to its Being, entrusted to its Being; it is the being who is concerned about its own Being. Heidegger then discerns two fundamental points that follow from this:

(1) {existentia over essentia} “The ‘essence’ of this being lies in its to be” (H.p.42)--it helps to read the “to be” as the translation of “Sein,” wherein instead of translating it as “Being,” we transliterate as “to be” to suggest that we are interested in the meaning of its being, that dynamic meaning, not substance.

Da-sein’s “whatness,” its objective presence (Vorhandenheit), its “essence,” its “essentia” must be understood in terms of its being (existentia). That is, we can only understand what Da-sein IS (its essence) by seeking to understand its existence, its existing (as itself). “The ‘essence’ of Da-sein lies in its existence” (H.p.42).

- Note: This (radically) reverses the tradition … we no longer seek Being’s essence and then, thereby, know its existence; instead, we can only know its essence by knowing its actual existence. Hence … the key premise: existence precedes essence.

(2) {always-being-mine} “The being which this being is concerned about in its being always my own” (H.p.42).

“Thus, Da-sein is never to be understood ontologically as a case and instance of a genus of beings as objectively present” (H.p.42). Remember this idea from the three prejudices in the Introduction I: Being is not a genus. So, this is not the Being as the highest category of distinction of which all those other things are species of it. Discussions of Da-sein should use the personal pronouns (e.g., I am, you are, we are, etc.). This follows from (1), above, because to understand the essence, we must understand existence.

Da-sein is my own. “The being which is concerned in its being about its being is related to its being as its truest possibility. Da-sein is always its possibility. It does not ‘have’ that possibility only as a mere attribute of something objectively present. And because Da-sein is always its possibility, it can ‘choose’ itself in its being, it can win itself, it can lose itself, or it can never and only ‘apparently’ win itself. It can only have lost itself and it can only have not yet gained itself because it is essentially possible as authentic, that is, it belongs to itself” (H.pp.42-3).

To embrace the existence (rather than starting with some essence), we embrace the dynamic possibility of Da-sein, of the being that is my own, in its full range of possibility. Possibilities are not attributes of a thing--e.g., that being could have brown hair or bad genes or good teeth—instead, they are Da-sein. All Da-sein is possible of choosing its way of being itself, authentically or inauthentically.

- (These terms will be explored at length later … here, just note that they can be thought of as ‘freely choosing’ and ‘avoiding choice’ and that the latter is not any lesser being, just a different way of being.)

Now … in addition to always choosing itself … Da-sein also already, somehow, understands itself (H.p.43). In the same way one might say you live in your own skin, so even if you haven’t thought really long and hard about what you mean, you do, by the fact of being you, have some degree of self-understanding.

Now, just because Da-sein has the character of being mine, and is studied in its existence, not essence, and because there is a natural understanding of it … this does not mean that Da-sein is Billy or Suzy or Zelda or Hans: “… this cannot mean that Da-sein is to be construed in terms of a concrete possible idea of existence” (H.p.43). Studied concretely, yes—in the sense of phenomenologically embedded in existence; but, not as a particular human being. Instead of differentiating one being to be Da-sein, we begin by looking indifferently … maybe a better way to say this is by saying we study a generic being who questions his or her own being. This is Heidegger’s “indifference of the everydayness of Da-sein,” the “averageness” of Da-sein (H.p.43).

We begin in this ontic everydayness …which Heidegger reemphasizes through quoting Augustine (“But what is closer to me than myself?”) and underscores the intensely anxious Saint’s response (“Assuredly I labor here and I labor within myself: I have become to myself a land of trouble and inordinate sweat”) (H.pp.43-4). This everydayness is the “a priori” of our study … it is not just a mere aspect of Da-sein, but the fundamental is-ness of it to which it always relates, either by embracing or fleeing.

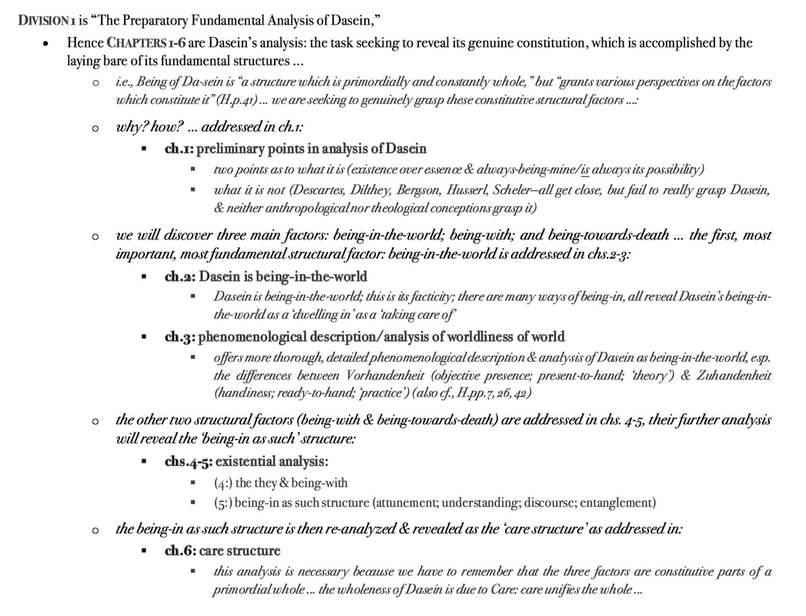

Now, Heidegger turns again to the differentiation of studying the ‘whatness’ (Vorhandenheit, the objective presence, the substance ontology he wants to depart from) versus the ‘thatness’ or ‘who’ (the existentials, the ontic-ontological phenomenological approach):

First, there is the easy distinction:

- ‘whatness’ is best directed to things (tables, decanters, guitars)*;

- ‘whoness’ is best directed to being (the being of beings) (H.p.44).

- *Heidegger does later add that ‘whatness’ can be turned to beings who are studied as things.

He includes here the interesting etymological cruise through “categories” (think in terms of Aristotle and Kant) understood more ontologically:

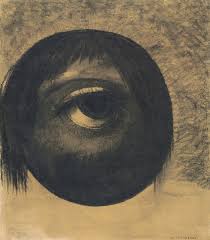

- “The being of these beings, however, must become comprehensible in a distinctive λεγειν [legein] (a letting be seen), so that this being is comprehensible from the very beginning as what it is and already is in every being. In the discussion (λογος [logos]) of beings, we have always already previously addressed ourselves to being; this addressing is kategoreisthai. That means, first of all: to accuse publically, to say something to someone directly and in front of everyone. Used ontologically, the term means: to say something to a being, so to speak, right in the face, to say what it always already is as a being; that is, to let it be seen for everyone in its being” (H.p.44).

In this quote, Heidegger is not referring us back to the Introduction’s discussion of legein and logos … instead, he is meaning that right here, now, in the world, when we undertake discussions with being, we have already presented ourselves. We have given ourselves as a ‘what’/‘who’ and demanded a revelation of their ‘what’/‘who’ … we can use “what” so long as we understand that this seemingly objective presentation isn’t so objective, but showing that conceals. Hence, our address of another is a self-showing of ourselves that asks the other to self-show him/herself. This address is a serious demand because the self-showing we ask for is as it/she/he is in itself already, always, and for all. A stunning passage … but Heidegger doesn’t help clarify that this sense is different from the sort of category used in substance ontology, in that type of study of being that he wants to get over and away from. He immediately then switches back to show how ‘what’ and ‘categories’ refer to the objective presence that we, beings, can be, but only when considered as things. (In the next chapter, we will see Heidegger working to rid us of any simple subject-object dichotomy, hence, I use this idea of ‘thingliness’ here carefully.)

§10

Heidegger then moves to differentiate the analytic of Da-sein from the sciences of anthropology, psychology, and biology. Essentially, none of these fields understand Da-sein at all. They chop up aspects and never ask the fundamental questions. Heidegger underlines this by again critiquing Descartes for not asking about the “sum,” about being, when naming us as the “thing that thinks” (H.pp.45-6). He also accuses us of dragging along this sort of unquestioned presumptions “no matter how energetic one’s ontic protestations against the ‘substantial soul’ or the ‘reification of consciousness’” (H.p.46) … is he cracking a joke here? Can’t we see the poor philosopher he disdains so much waving about his arms saying no, no, no, there is no ‘soul,’ even as his thesis has presumed the same exact structure, just now has called it ‘geist’ or ‘flux’ or what have you?

Then, while psychology gets is just as wrong as anthropology and biology, Heidegger is complementary of Scheler and Husserl’s attempt to move away from psychology and, instead, adopt a notion of the person or psyche as the “immediately co-experienced unity of ex-periencing” (H.p.47), or, easier said, as neither a thing, nor a substance, nor even an object. However, even this does not go as far as Heidegger himself will go with his radical notion of Da-sein.

Anthropology’s biggest problems are two: interpreting the human as the rational animal or as the theological one (H.pp.48-9). To do either of these is to fall prey to the prejudices against being raised in the Introduction I.

Biology goes wrong because it reduces the study to “life.” Surely, life has a kind of being, but we can only access what this is through the fundamental analytic of Da-sein. And, life is neither Da-sein itself, nor some simple attribute of Da-sein (H.p.50).

§11

Now, returning to anthropological sort of concerns, Heidegger needs to clarify that his average everydayness is fundamental, natural, and simple, but certainly not the same as “primitive” in the sense of ancient cave people, etc.: “Everydayness is not the same thing as primitiveness” (H.p.50). So, when we uncover these essential structures of Da-sein, we are not going to be dealing with some pre-evolutionary traits, instincts, etc.

Heidegger then ends the section and chapter remarking on the “world,” which is of utmost importance to understand in order to understand Da-sein. “World” itself will be constitutive of Da-sein, it is what makes Da-sein who Da-sein is, and it is what will reveal the structures. This world is not made clearer at all by simply laying out a bunch of information (geographical, statistical, poetic, or otherwise).

|

... Interlude ...

A somewhat absurd SUMMARY of what we know so far about ~~ Dasein ~~ from the two Introduction Chapters and Chapter One: Dasein is:

|

Chapter Two:

Being-in-the-World in General as the Fundamental Constitution of Da-sein

{ ... notes will be polished up a bit and expanded, soon ... }

§12

A Preliminary Sketch of Being-in-the-World in Terms of the Orientation toward Being-in as such:

Heidegger begins by summing up Da-sein as the being who is concerned (related understandingly) in its being toward that being … this emphasizes the fact that the formal aspect of Da-sein that we are talking about is its existence … and, that this existence is mine, that being which I myself always already am … and that this mineness relates to existing Da-sein as the condition of its possibility of authenticity and inauthenticity (which are modes in which Da-sein exists even if and when it pays no attention to them).

Now … we must understand this idea of Da-sein as “a priori grounded upon that constitution of being which we call being-in-the-world” (H.p.53).

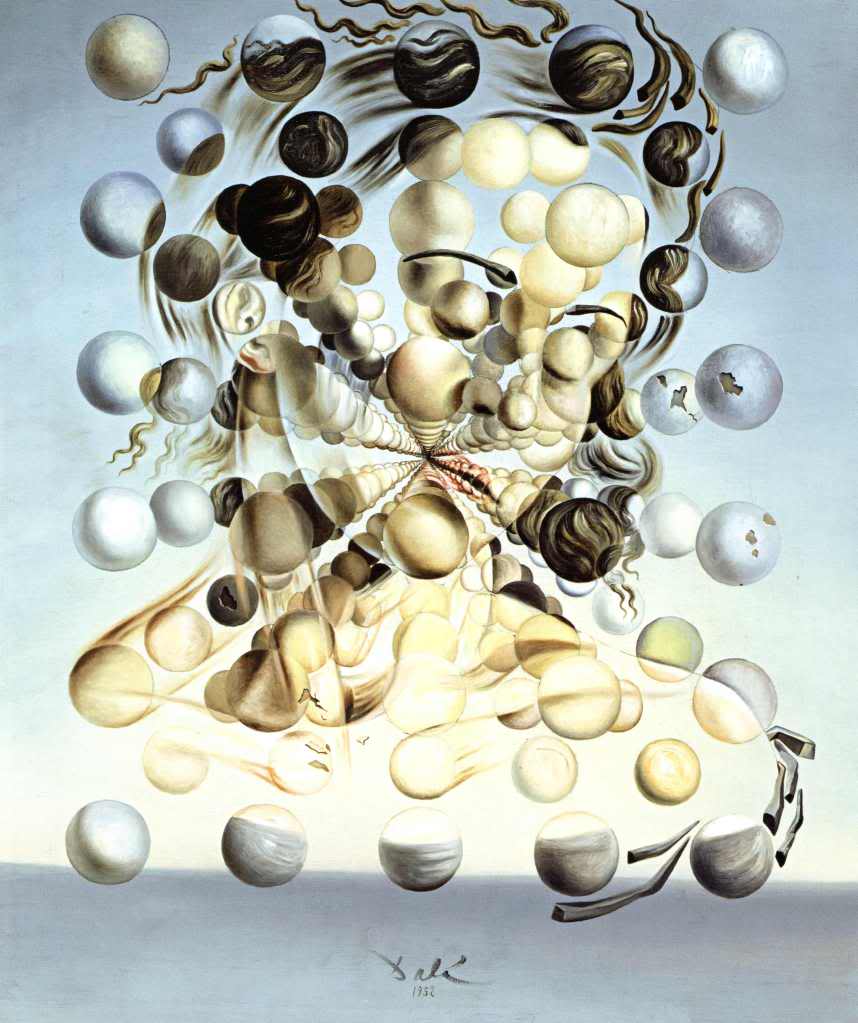

“Being-in-the-World” indicates a “unified phenomenon” (H.p.53) … we will come to see how experience is that which unifies the diversity of being-nesses into a singular, multi-dimensional phenomenon (presentation). We will not break up its unity to look at each facet, but we can come to see how it has several constitutive structural factors (i.e., there are various structures that make up this unity).

Specifically, we will see three perspectives from this unified phenomenon of being-in-the-world:

To examine any one of these three elements will also reveal the other two, for this is, remember, a unified phenomenon. Understanding these three perspectives reveal the a priori foundation of Da-sein, but they certainly don’t give us the entire picture of the meaning of being.

So … what does “Being-in” mean?

To start understanding it, we think of being-in something, hence we supplement the phrase with the “the world:” being-in-the-world. All of the spatial situatedness given by “in’s” show us the kind of being of objective presence (the whatness, Vorhandenheit)—e.g., the water is in the cup, which is on the table, which is in the kitchen, which is in the house, which is in Nashville, etc. If we consider this theoretically (ontologically), we have identified the categorical relation (cf. categories versus existentials and the etymology of Kategoreisthai, H.pp.44-45) of this sort of being as thing, but this doesn’t at all tell us about the being specific to Da-sein.

So … we need to understand the existential being-in, which will be a constitution of the being of Da-sein. This will not be the spatial what-ness of a thing. Heidegger leads us to understanding this through etymology:

“Being-in is thus the formal existential expression of the being of Da-sein which has the essential constitution of being-in-the-world” (H.p.54).

Heidegger then moves to expounding “Being together with the world,” which is in the sense of being absorbed in the world. Like above, he first explains this negatively—what it is not.

So … “Being together with the world” is not a “being-objectively-present-together of things” (H.p.55). Tables and chairs can be objectively present in the sense of the chair is by the table. This is one thing spatially by another thing. He takes this idea of “next to” to the level of “touching,” then says that “Strictly speaking, we can never talk about ‘touching’” … first, because there will always be space (in the physics sense) between one thing and another thing … but, even if there wasn’t any space at all, this “touching” would presumptively be the chair encountering the table … and things can never encounter things. Only the kind of being that has Being-in as its fundamental existential structure and has, thereby, a world, can encounter. Objectively present things, on the contrary, are worldless; they cannot touch, they cannot encounter.

(Sure, Da-sein could understand itself as objectively present, but this presupposes that it is a being-in fundamentally that is then adopting a different perspective whereby to view its thingliness.)

“Da-sein understands its ownmost being in the sense of a certain ‘factual objective presence.’ And yet the ‘factuality’ of the fact of one’s own Da-sein is ontologically totally different from the factual occurrence of a kind of stone. The factuality of the fact Da-sein, as the way in which every Da-sein actually is, we call its facticity” (H.p.56).

(So … the “factuality” of Da-sein is its “facticity.”)

Now … this facticity leads us to many, many mistaken presumptions about how we are IN the world.

We cannot at all understand the sort of facticity of Da-sein, of Da-sein’s spatiality, in terms of thinking of some spiritual quality as our being-in-the-world and some sort of bodily quality as our spatial being. We cannot have a dualism of mind/body or spirit/body to think our ‘in-ness.’

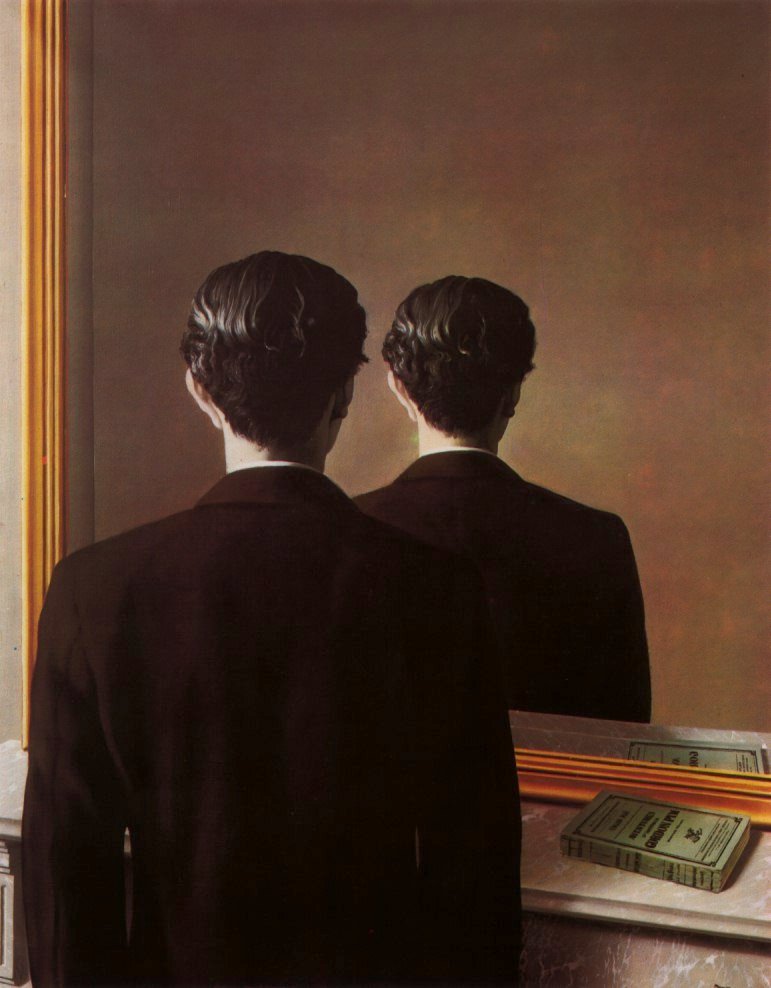

So … some will then think of our in-ness through definite, different ways of being in in the ontic sense: having to do with something, to produce, to order, to take care of, to use, to get lost, to accomplish, to find out, to ask, etc., etc., etc. These are different ontic understandings of how we are in the world (in it as using it, as lost in it, etc.), but these are only ways of “taking care of,” which is a kind of being of being-in, but must be understood ontologically. In other ways … these everyday language ways of thinking being-in point to “taking care of;” this is very important, but so long as we think ontically, it won’t help us understand anything meaningful. So …

Taking-care-of can, in the everyday ontic sense, mean things like: carrying something out, settling something up, getting it for oneself, etc.

In the ontological sense, taking care will be a fundamental structure of Da-sein, it will designate the being of a possible being-in-the-world. “… the being of Da-sein itself is understood to be made visible as care” (H.p.57). Because Being-in-the-world belongs fundamentally to Da-sein, its being towards the world is essentially taking care.

So … back to “being-in” … It is not a quality had by being. It is not something being sometimes has and sometimes doesn’t. It is not that being first is and then it is in. It is not a relation Da-sein has to something. Any relations at all are only, ever possible because Da-sein first is being-in (H.p57). Relations never come about because something in the world meets up with you, bumps up against you; instead, such meeting is only ever possible for a being who is the kind of being that is being-in.

“Environment” is a pretty good term for this sort of world (as is “surroundings”), but Heidegger disdains it a bit because of how we use those terms … typically as something one has, which is utterly opposite to his idea of world.

He then comments on how and why he uses so many negative definitions (what being-in is not) … explaining that this is because of the very ontic nature of Da-sein itself that is initially and fundamentally understanding in some basic way of its in-ness and world. Unfortunately, these everyday understandings lead to all sorts of mistaken views of our being in the world. Typically, and the most dangerous mistake is presuming a subject-object dichotomy. This mistake, he says, is FATAL (H.p.58). We are led to this mistake because we misunderstand “knowing.”

§13:

Da-sein and the world are NOT subject and object (H.p.60).

Knowing is not an objective presence … it is not some catalogue of aspects of things, it is not a knowing of external characteristics. Because we presume it is, we then fall into the trap of thinking how does my knowing (which is IN me) know what is OUT there. And then we fall into a sticky trap of how can I know if what I know in here accurately corresponds to what is out there. Get rid of all these presumptions.

Instead, “Knowing is a mode of being of Da-sein as being-in-the-world, and has its ontic foundation in this constitution of being” (H.p.61).

“… knowing itself is grounded beforehand in already-being-in-the-world which essentially constitutes the being of Da-sein” (H.p.61). This knowing is NOT a staring at things. “Being-in-the-world, as taking care of things, is taken in by the world which it takes care of. In order for knowing to be possible as determining by observation which is objectively present, there must first be a deficiency of having to do with the world and taking care of it” (H.p.61).

In other words, knowing as a knowing about things is only, only possible when we step outside of our actual selves, step outside of our natural practice and dwelling within the world, and theorize about things abstractly. This ‘looking’ is a mode of being we can take on; therein things can present themselves, we can address them and discuss them as an activity of perception, which becomes definition, which can then be put into propositions about them and stored away as information. This is not the same inside/outside problem, but it IS a being-outside-of-the-self-already-as-a-self-being-in-the-world (H.p.62).

This gives us a new perspective of the world that is and was always already discovered in Da-sein. Hence, “Knowing is a mode of Da-sein which is founded in being-in-the-world. Thus, being-in-the-world, as a fundamental constitution, requires a prior interpretation” (H.p.62).

click on the following to go to ~ CHAPTER Three NOTES ~

Being-in-the-World in General as the Fundamental Constitution of Da-sein

{ ... notes will be polished up a bit and expanded, soon ... }

§12

A Preliminary Sketch of Being-in-the-World in Terms of the Orientation toward Being-in as such:

Heidegger begins by summing up Da-sein as the being who is concerned (related understandingly) in its being toward that being … this emphasizes the fact that the formal aspect of Da-sein that we are talking about is its existence … and, that this existence is mine, that being which I myself always already am … and that this mineness relates to existing Da-sein as the condition of its possibility of authenticity and inauthenticity (which are modes in which Da-sein exists even if and when it pays no attention to them).

Now … we must understand this idea of Da-sein as “a priori grounded upon that constitution of being which we call being-in-the-world” (H.p.53).

“Being-in-the-World” indicates a “unified phenomenon” (H.p.53) … we will come to see how experience is that which unifies the diversity of being-nesses into a singular, multi-dimensional phenomenon (presentation). We will not break up its unity to look at each facet, but we can come to see how it has several constitutive structural factors (i.e., there are various structures that make up this unity).

Specifically, we will see three perspectives from this unified phenomenon of being-in-the-world:

- (1) “In-the-world”—which will, in our study, reveal the worldliness of the world (cf. chapter three);

- (2) “The being which always is in the way of being-in-the-world”—which will reveal the “who-ness” of the being, that is, the average everydayness of Da-sein (cf. chapter four);

- (3) “Being in as such”—which will reveal the ontological constitution of the “in-ness” (cf. chapter five)

To examine any one of these three elements will also reveal the other two, for this is, remember, a unified phenomenon. Understanding these three perspectives reveal the a priori foundation of Da-sein, but they certainly don’t give us the entire picture of the meaning of being.

So … what does “Being-in” mean?

To start understanding it, we think of being-in something, hence we supplement the phrase with the “the world:” being-in-the-world. All of the spatial situatedness given by “in’s” show us the kind of being of objective presence (the whatness, Vorhandenheit)—e.g., the water is in the cup, which is on the table, which is in the kitchen, which is in the house, which is in Nashville, etc. If we consider this theoretically (ontologically), we have identified the categorical relation (cf. categories versus existentials and the etymology of Kategoreisthai, H.pp.44-45) of this sort of being as thing, but this doesn’t at all tell us about the being specific to Da-sein.

So … we need to understand the existential being-in, which will be a constitution of the being of Da-sein. This will not be the spatial what-ness of a thing. Heidegger leads us to understanding this through etymology:

- “In” stems from innan-, to live, habitare, to dwell.

- “An” means I am used to, familiar with, I take care of something (it means “colo” (dwell, live, inhabit) in the sense of habito (live, abide, reside, lodge) and diligo (love, value, distinguish by choosing).

- The “In” part of Being-in, then, is a familiar dwelling in concernfully.

- He then links the German “bin” (am) with “bei” (near, by, with), understanding “Ich bin” (I am) as “I dwell, I stay near”) (H.p.54).

- The “Being” part of Being-in, then, is a nearness of dwelling, the familiar world that is mine.

“Being-in is thus the formal existential expression of the being of Da-sein which has the essential constitution of being-in-the-world” (H.p.54).

Heidegger then moves to expounding “Being together with the world,” which is in the sense of being absorbed in the world. Like above, he first explains this negatively—what it is not.

So … “Being together with the world” is not a “being-objectively-present-together of things” (H.p.55). Tables and chairs can be objectively present in the sense of the chair is by the table. This is one thing spatially by another thing. He takes this idea of “next to” to the level of “touching,” then says that “Strictly speaking, we can never talk about ‘touching’” … first, because there will always be space (in the physics sense) between one thing and another thing … but, even if there wasn’t any space at all, this “touching” would presumptively be the chair encountering the table … and things can never encounter things. Only the kind of being that has Being-in as its fundamental existential structure and has, thereby, a world, can encounter. Objectively present things, on the contrary, are worldless; they cannot touch, they cannot encounter.

(Sure, Da-sein could understand itself as objectively present, but this presupposes that it is a being-in fundamentally that is then adopting a different perspective whereby to view its thingliness.)

“Da-sein understands its ownmost being in the sense of a certain ‘factual objective presence.’ And yet the ‘factuality’ of the fact of one’s own Da-sein is ontologically totally different from the factual occurrence of a kind of stone. The factuality of the fact Da-sein, as the way in which every Da-sein actually is, we call its facticity” (H.p.56).

(So … the “factuality” of Da-sein is its “facticity.”)

Now … this facticity leads us to many, many mistaken presumptions about how we are IN the world.

We cannot at all understand the sort of facticity of Da-sein, of Da-sein’s spatiality, in terms of thinking of some spiritual quality as our being-in-the-world and some sort of bodily quality as our spatial being. We cannot have a dualism of mind/body or spirit/body to think our ‘in-ness.’

So … some will then think of our in-ness through definite, different ways of being in in the ontic sense: having to do with something, to produce, to order, to take care of, to use, to get lost, to accomplish, to find out, to ask, etc., etc., etc. These are different ontic understandings of how we are in the world (in it as using it, as lost in it, etc.), but these are only ways of “taking care of,” which is a kind of being of being-in, but must be understood ontologically. In other ways … these everyday language ways of thinking being-in point to “taking care of;” this is very important, but so long as we think ontically, it won’t help us understand anything meaningful. So …

Taking-care-of can, in the everyday ontic sense, mean things like: carrying something out, settling something up, getting it for oneself, etc.

In the ontological sense, taking care will be a fundamental structure of Da-sein, it will designate the being of a possible being-in-the-world. “… the being of Da-sein itself is understood to be made visible as care” (H.p.57). Because Being-in-the-world belongs fundamentally to Da-sein, its being towards the world is essentially taking care.

So … back to “being-in” … It is not a quality had by being. It is not something being sometimes has and sometimes doesn’t. It is not that being first is and then it is in. It is not a relation Da-sein has to something. Any relations at all are only, ever possible because Da-sein first is being-in (H.p57). Relations never come about because something in the world meets up with you, bumps up against you; instead, such meeting is only ever possible for a being who is the kind of being that is being-in.

“Environment” is a pretty good term for this sort of world (as is “surroundings”), but Heidegger disdains it a bit because of how we use those terms … typically as something one has, which is utterly opposite to his idea of world.

He then comments on how and why he uses so many negative definitions (what being-in is not) … explaining that this is because of the very ontic nature of Da-sein itself that is initially and fundamentally understanding in some basic way of its in-ness and world. Unfortunately, these everyday understandings lead to all sorts of mistaken views of our being in the world. Typically, and the most dangerous mistake is presuming a subject-object dichotomy. This mistake, he says, is FATAL (H.p.58). We are led to this mistake because we misunderstand “knowing.”

§13:

Da-sein and the world are NOT subject and object (H.p.60).

Knowing is not an objective presence … it is not some catalogue of aspects of things, it is not a knowing of external characteristics. Because we presume it is, we then fall into the trap of thinking how does my knowing (which is IN me) know what is OUT there. And then we fall into a sticky trap of how can I know if what I know in here accurately corresponds to what is out there. Get rid of all these presumptions.

Instead, “Knowing is a mode of being of Da-sein as being-in-the-world, and has its ontic foundation in this constitution of being” (H.p.61).

“… knowing itself is grounded beforehand in already-being-in-the-world which essentially constitutes the being of Da-sein” (H.p.61). This knowing is NOT a staring at things. “Being-in-the-world, as taking care of things, is taken in by the world which it takes care of. In order for knowing to be possible as determining by observation which is objectively present, there must first be a deficiency of having to do with the world and taking care of it” (H.p.61).

In other words, knowing as a knowing about things is only, only possible when we step outside of our actual selves, step outside of our natural practice and dwelling within the world, and theorize about things abstractly. This ‘looking’ is a mode of being we can take on; therein things can present themselves, we can address them and discuss them as an activity of perception, which becomes definition, which can then be put into propositions about them and stored away as information. This is not the same inside/outside problem, but it IS a being-outside-of-the-self-already-as-a-self-being-in-the-world (H.p.62).

This gives us a new perspective of the world that is and was always already discovered in Da-sein. Hence, “Knowing is a mode of Da-sein which is founded in being-in-the-world. Thus, being-in-the-world, as a fundamental constitution, requires a prior interpretation” (H.p.62).

click on the following to go to ~ CHAPTER Three NOTES ~

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by MacHighway