Saint Augustine

Augustine's influence was immense through the medieval philosophy and theology, continued to deeply impact modern and contemporary thought, as well as having profound influence in many other disciplines. In particular, his Confessions is considered the first and an otherwise exemplar of autobiography. Augustine is a remarkable figure for philosophy as he was the principle lead in the merging of Greek philosophy, predominately Neoplatonism, with Abrahamic religious traditions.

In addition to his Confessions (397-401), Augustine left us an enormous amount of writing—over 100 works, over 200 letters, and nearly 400 sermons—some of his other most notable writings include: Contra Academicos [Against the Academicians, 386-7], De Libero Arbitrio [On the Free Choice of the Will, written over a long period, ca. 387-95], De Magistro [On the Teacher, 389], and De Civitate Dei [On the City of God, 413-27].

In addition to his Confessions (397-401), Augustine left us an enormous amount of writing—over 100 works, over 200 letters, and nearly 400 sermons—some of his other most notable writings include: Contra Academicos [Against the Academicians, 386-7], De Libero Arbitrio [On the Free Choice of the Will, written over a long period, ca. 387-95], De Magistro [On the Teacher, 389], and De Civitate Dei [On the City of God, 413-27].

Contents:

- Augustine's Life

- Augustine's Philosophy

- On Augustine's Confessions

- Textual Analysis of Confessions

- Key Ideas and Questions

1. Augustine's Life

Saint Augustine was born Aurelius Augustinus in Thagaste (a municipality now in Algeria, then under Roman rule) in 354 C.E. to parents Monica (a Christian) and Patricius (a pagan public official), and died in Hippo in August of 430 C.E. (just as Vandals were attacking the gates of the city).

Augustine, by Sandro Botticelli

Augustine, by Sandro Botticelli

Childhood: He was born and first studied at Thagaste, a municipality now in Algeria (then under Roman rule), to become public official like his father, Patricius. Monica, his mother, was Christian and provided his mild exposure to Christ, while his father was Pagan. In his infancy, he determined that words are signs of things, we speak so that our will might be obeyed. The adult Augustine begs that the innocent errors of children should be corrected; as example of such an error, he remarks that he preferred God’s creatures to God. We also learn that he preferred grammar to literature.

At about 11 years old, Augustine was sent to Madauras (from about 365-369) to continue his studies (ars gammatica, reading Greek history and myth, Pagan authors), and admits that he loved the Latin classics, especially Virgil, but was quite turned off by the Greeks.

At about 11 years old, Augustine was sent to Madauras (from about 365-369) to continue his studies (ars gammatica, reading Greek history and myth, Pagan authors), and admits that he loved the Latin classics, especially Virgil, but was quite turned off by the Greeks.

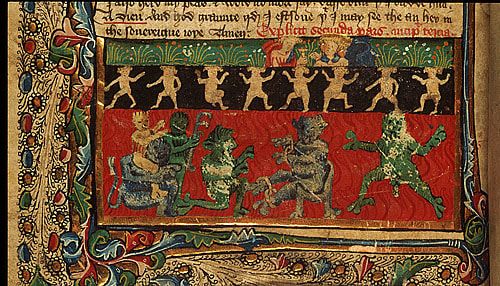

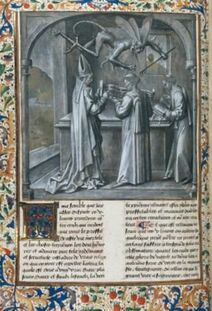

Medieval Illuminated Manuscript showing St. Augustine before the demons.

Medieval Illuminated Manuscript showing St. Augustine before the demons.

During a break from school, at about 16 years old, Augustine was back in Thagaste and hand an experience that marked his early life and epitomized his life's spiritual, intellectual, and religious quests: with a gang of his friends, he breaks into a neighbor's garden where they steal pears--the boys had no desire to eat them, only to steal them, or, as he repeats, to sin out of lust. This experience leads Augustine to seek to define sin so to understand why he did it. Definitions he explores include: reflections on how people like what is least good and thereby turn from things of greatest good, God; that people do not sin for the sake of sin, but for some end; and that sinning is a perverse imitation of God. He eventually concludes that sin proves God is the creator; that evil is done by humans' free will; and that the whole avoidance of evil by God’s grace.

As Augustine approaches about 18 years old, ca. 370, we learn that he loved theatrical shows, which lead him to question why people find pleasure in feeling sorrow while watching tragedy. He is now a student of rhetoric at Carthage and most momentously reads Cicero’s Hortensius (only fragments of this work survive) and was greatly moved and inspired by its wisdom. This is his first conversion, in a sense, one to philosophy. Philosophy, for Augustine, was whole pursuit of wisdom, and his obsession with the question of evil was a personal and very visceral question about how to best live one’s life. Sometime around this period he began a 13-year monogamous relationship with a woman who gave him his son, Adeodatus (born 372).

Intellectually and existentially, Augustine deeply questions during this period why Christ is missing in Cicero. He reads the Scriptures, but is unconvinced, finds them simple, too humble. Monica, his mother, dreams he will find his path and she ought to direct him.

In his 20’s Augustine became a Manichaean (remaining one for 9-15 years, depending on accounts), eventually abandoning the belief due to rational inconsistencies), while teaching rhetoric in Thagaste and Carthage, where he had child (Adeodatus, born 372) by his 13-year monogamous mistress. After abandoning Manichaeism, he takes up a teaching position in Rome around 381 (at about 29 years old). It was a risky journey, but he was seeking the ‘better’ students rumored to be there; he is there exposed to the philosophical schools of skepticism, and, his students, while he found them somewhat better, they had the habit of refusing to pay for lessons, and so he leaves Rome. He then moves to Milan, encountering St. Ambrose and Neoplatonism (namely in the vein of Plotinus). He learns four important things from Ambrose: 1) the Scriptures need not be interpreted as literal; 2) that spiritual reality has nothing to do with matter; 3) that evil is nothing, a privation; and 4) that moral evil is from free will, not an evil principle. These lessons move him more towards Christianity--helping him to better understand the problem of evil and how to think God as non-substantial--but, though his mind was ready to convert, his will was not, especially due to his desire for his mistress. Either for this reason, or, because during this time he was encouraged to consider an arranged marriage, he separated from his mistress and son. Soon after, he abruptly resigned his teaching post (ca. 386) and renounced his academic ambitions. Further inspiring encounters follow: he learns about Victorinus’ conversion (an African rhetor converted to Christianity) and then about two court attendants who met ascetics, read St. Anthony, and converted on the spot. Augustine then reads Paul (which aids his complete separation from the mistress and from all sexual relations). In a dramatic scene with his friend in his mother's garden, both desperate for conversion, he hears a child’s voice in a nearby garden calling out "tolle, legge," to pick it up and read it, and interprets it as a command from God. He picks up, opens up the Bible, and his conversion to Christianity happens.

Thereafter, he completely abandons rhetoric, yet spends four months at Cassiciacum writing his earliest works that survive. His son, Adeodatus, dies at age 17. Augustine baptized by Bishop Ambrose on Easter Sunday in 387 at 33 years old. He then moves, in the Confessions, to recall his life and reflect upon the death of his mother Monica at Ostia, outside of Rome. Augustine then returns to Thagaste.

In 391, he was ordained as a priest in Hippo, in North Africa, soon after becoming the Bishop of Hippo. Eventually he was named a Doctor and Saint of the Roman Catholic Church. He died there in Hippo in August of 430 (just as Vandals were attacking the gates of the city).

2) Augustine's Philosophy

There are two key philosophical issues to be explored in Augustine’s work: (1) The interplay of faith and reason and (2) the problem of evil. These will be explored in depth below, but can be summed up here as an introduction:

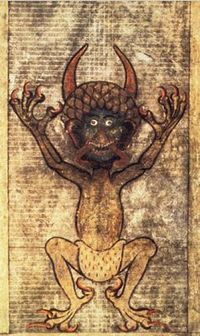

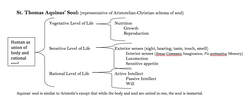

Augustine teaching two clerks as a demon flies overhead

Augustine teaching two clerks as a demon flies overhead

(1) The Interplay of Faith and Reason:

Augustine, like Plato, privileged non-dogmatic reason (our ability to know): The highest truth, for Plato, was a grasp of the form of the Good. Augustine’s interpretation of the Good is either God or the Happy Life.

Consider the Platonic idea of the Good, such is universally and eternally true and, while experience can mislead us (being only mere representations of the form), the employment of reason can permit one to know the Good to some degree. Since Augustine was a strong adherent to Neoplatonism, we would assume that he would privilege the side of Reason over Faith. We receive a strong sense of this necessity for reason when he is defending religious convictions against those who do not believe, for example, as he writes:

However, the problem is more complex and rarely does he rely upon reason alone. In fact, the Confessions reveals his reliance on reason as the greatest hindrance to his full acceptance of faith.

The complexity may be understood by considering his Neoplatonist inheritance. The forms may be universal, knowable truths, but that does not mean we have perfect knowledge of them. Socrates personifies the theory of the forms by explaining our souls have contact with them prior to embodiment and after our bodily deaths; not all souls have full access because one’s access to the forms depends upon the life that one has lived, if one has trained the mind properly to ‘see’ the forms.

So, like how the dialogues’ instructional wisdom rests in their conclusion in aporia, the beauty of the forms is representing the possibility humanity has to know truth though instruction and reflection.

Likewise, in Augustine: In On the Free Choice of the Will, II, he quotes Isaiah, “Unless you believe, you shall not understand” (11). Further, he says,

For Augustine, the foundational premise for the Good, for the Happy Life, is FAITH: “Unless you believe, you shall not understand.” BUT, Reason is that tool which permits understanding of that truth in which we believe. Reason extends and deepens faith. And reason can initiate faith: for the disbeliever may use reason alone to start moving toward God—thus, making reason a preparation for faith.

This interplay of faith and reason is not just an intellectual endeavor for both Plato and Augustine.

The interesting undercurrent to this struggle for understanding, which must be conducted through both reason and faith, is that one struggles against desires by the strength of one’s desire. Augustine describes what happens when LUST dominates the mind:

The first three “storms” caused by the reign of lust are TERROR, DESIRE, and ANXIETY; these storms distract us from “enlightenment,” or understanding the truth, from faith in God. But, as we will see in the Confessions, the REIGN OF LUST produces the same emotional and spiritual ill-ease that is born out of the PURSUIT OF KNOWLEDGE (as understood as living).

Could Augustine attain understanding, attain faith, without knowing the struggles of lust? Does one not need to be able to see the symmetry between desiring good and ill? Socrates claimed that his wisdom was his acknowledgement of his own ignorance; only if one recognizes one’s ignorance can one know what knowledge to look for. The only positive statement he ever made about his wisdom was to claim he knew the art of seduction. This is the same lesson we find in the etymology of “educate” and “seduce” as both born from the Latin root ducere, “to lead.” The abbreviated ex in educere renders its meaning “to lead out” and the se of seducere “to lead away.” Presumably, what one is led out of or away from is ignorance.

This gives us a new insight into this paradox of banishing desires by one’s desire and this struggle most central to one’s life in this world not only suggests the complexity of the interplay between faith and reason, but it also reveals Augustine’s central concern: Augustine was haunted by the Problem of Evil.

Augustine, like Plato, privileged non-dogmatic reason (our ability to know): The highest truth, for Plato, was a grasp of the form of the Good. Augustine’s interpretation of the Good is either God or the Happy Life.

Consider the Platonic idea of the Good, such is universally and eternally true and, while experience can mislead us (being only mere representations of the form), the employment of reason can permit one to know the Good to some degree. Since Augustine was a strong adherent to Neoplatonism, we would assume that he would privilege the side of Reason over Faith. We receive a strong sense of this necessity for reason when he is defending religious convictions against those who do not believe, for example, as he writes:

- I presented my arguments against these men [the Manicheans] … it was impossible to bring up the authority of Sacred Writ in opposition to such perversion … By means of irrefutable argumentation (which I actually accomplished without direct appeal to the truth of any part of the Holy Writ) I showed that God should be praised for all things, and that there are no grounds at all for their belief that there exists two co-eternal natures, one good, one evil … (Augustine, De dono perseverantiae 6).

However, the problem is more complex and rarely does he rely upon reason alone. In fact, the Confessions reveals his reliance on reason as the greatest hindrance to his full acceptance of faith.

The complexity may be understood by considering his Neoplatonist inheritance. The forms may be universal, knowable truths, but that does not mean we have perfect knowledge of them. Socrates personifies the theory of the forms by explaining our souls have contact with them prior to embodiment and after our bodily deaths; not all souls have full access because one’s access to the forms depends upon the life that one has lived, if one has trained the mind properly to ‘see’ the forms.

So, like how the dialogues’ instructional wisdom rests in their conclusion in aporia, the beauty of the forms is representing the possibility humanity has to know truth though instruction and reflection.

Likewise, in Augustine: In On the Free Choice of the Will, II, he quotes Isaiah, “Unless you believe, you shall not understand” (11). Further, he says,

- "… do you think there is anything more excellent than a rational and wise mind? [Evodius answers:] Nothing, I think, except God. [Augustine says:] This is my opinion too. But though we accept this with the strongest faith, understanding it is a very difficult matter" (Augustine, On the Free Choice of the Will, bk. II).

For Augustine, the foundational premise for the Good, for the Happy Life, is FAITH: “Unless you believe, you shall not understand.” BUT, Reason is that tool which permits understanding of that truth in which we believe. Reason extends and deepens faith. And reason can initiate faith: for the disbeliever may use reason alone to start moving toward God—thus, making reason a preparation for faith.

This interplay of faith and reason is not just an intellectual endeavor for both Plato and Augustine.

- For Plato: To use reason to come to know/understand the truth of the FORMS is the utmost struggle one undertakes in life. In his dialogues, Socrates is always presented as the “Gad Fly” (an aimlessly wandering, buzzing, annoying insect), pestering Athens’ citizens; his interlocutors always begin pompously declaring their wisdom concerning X and end having their ignorance put on display before them as they quickly run away from Socrates and further dialogue. Socrates was put on trial and sentenced to death partially for this essential disagreeableness Athens found with his pursuit of wisdom insofar as it involved questioning themselves. At his trial, he says, “the unexamined life is not worth living.” This examination of life is the reflection upon the forms so as to know and know how to pursue the Good Life.

- Likewise For Augustine: Understanding is both difficult—as in the quote above and when he remarks, “… mind can be present in man, and yet not have control” (ibid.)--and an absolutely necessary endeavor. In his On the Free Choice of the Will and in the Confessions we see his profound struggle with coming to know the truth. The texts reveal how easy it is have the mind seduced by the lower faculties of soul and become disordered. There are many unhappy ones who seek those temporal things as opposed to the eternal; who seek those things which can be lost against one’s will and lead one to despair and away from understanding truth. The texts also advise the wise ones to cultivate the four cardinal virtues (prudence, fortitude, temperance, and justice) to avoid evil willing. So Augustine, like Plato, saw the attainment of the Happy/Wise Life as a difficult and necessary struggle.

The interesting undercurrent to this struggle for understanding, which must be conducted through both reason and faith, is that one struggles against desires by the strength of one’s desire. Augustine describes what happens when LUST dominates the mind:

- "… the reign of lust rages tyrannically and distracts the life and whole spirit of man with many conflicting storms of terror, desire, anxiety, empty and false happiness, torture because of the loss of something that he used to love, eagerness to possess what he does not have, grievances for injuries received, and fires of vengeance" (Augustine, On the Free Choice of the Will, Bk.I).

The first three “storms” caused by the reign of lust are TERROR, DESIRE, and ANXIETY; these storms distract us from “enlightenment,” or understanding the truth, from faith in God. But, as we will see in the Confessions, the REIGN OF LUST produces the same emotional and spiritual ill-ease that is born out of the PURSUIT OF KNOWLEDGE (as understood as living).

Could Augustine attain understanding, attain faith, without knowing the struggles of lust? Does one not need to be able to see the symmetry between desiring good and ill? Socrates claimed that his wisdom was his acknowledgement of his own ignorance; only if one recognizes one’s ignorance can one know what knowledge to look for. The only positive statement he ever made about his wisdom was to claim he knew the art of seduction. This is the same lesson we find in the etymology of “educate” and “seduce” as both born from the Latin root ducere, “to lead.” The abbreviated ex in educere renders its meaning “to lead out” and the se of seducere “to lead away.” Presumably, what one is led out of or away from is ignorance.

This gives us a new insight into this paradox of banishing desires by one’s desire and this struggle most central to one’s life in this world not only suggests the complexity of the interplay between faith and reason, but it also reveals Augustine’s central concern: Augustine was haunted by the Problem of Evil.

(2) The Classic Problem of Evil:

The problem arises from the conflicts that come from three of God’s most essential attributes:

Specifically, the conflict comes from the questions that thus follow: If God is all-good, and evil exists, and he neither is nor does evil, how can he know evil? If God is all-good, and evil exists, and he neither is nor does evil, then how can he be all-powerful?

Further, God’s omnipotence determines him to be the creator of everything. However, God is also absolutely good; so, if he created everything, than he must have created evil, but if he is all-good, then he cannot have created evil. Therefore, since there is evil in the world, either God did not create it, thus not all-powerful, or he did create evil and he is thus not all good.

Thus, how can evil have come to be and still exist in the world without diminishing God?

This problem drives Augustine’s long and torturous path to religious conversion ... hence, it is sensible to now turn to Confessions:

The problem arises from the conflicts that come from three of God’s most essential attributes:

- God is omniscient (sees/knows all),

- omnipotent (all-powerful), and

- omnibenevolent (all-good).

Specifically, the conflict comes from the questions that thus follow: If God is all-good, and evil exists, and he neither is nor does evil, how can he know evil? If God is all-good, and evil exists, and he neither is nor does evil, then how can he be all-powerful?

Further, God’s omnipotence determines him to be the creator of everything. However, God is also absolutely good; so, if he created everything, than he must have created evil, but if he is all-good, then he cannot have created evil. Therefore, since there is evil in the world, either God did not create it, thus not all-powerful, or he did create evil and he is thus not all good.

Thus, how can evil have come to be and still exist in the world without diminishing God?

This problem drives Augustine’s long and torturous path to religious conversion ... hence, it is sensible to now turn to Confessions:

3) On Augustine's Confessions

The Confessions is Augustine's autobiographical exploration of his anxiety-ridden religious conversion to Christianity written in thirteen books, or chapters, where the first nine span his memories of his past from infancy to about age 33, book ten is an examination of memory, and books eleven to thirteen discuss his philosophy of time, eternity, and an exegesis on the opening book of Genesis.

- Bks. I-IX: Present time of things past: Memory of Past:

- Conversion journey from infancy to 33

- Bk. X: Present time of things present: Intuition of Present:

- Current difficulties as recalling past events and discussion of memory

- Bks. XI-XIII: Present time of things future: Expectation of Future:

- Exegesis on Genesis and on time and eternity

This layout strikes some as strange if the work is considered only an autobiography about a Saint’s search for happiness (conceived as a state of ease and lack of anxiety) and truth that lead to his religious conversion. Book X, however, reveals a way for us to consider the form of his text as a demonstration of his philosophy of memory and time. Remembering that the theme “a quest to know God” in many ways epitomizes medieval philosophy, Augustine's Confessions can easily be seen as its preeminent examination, as the work that thoroughly delineates and embodies the knowing, the act of seeking this knowledge.

The Confessions begins: “How can I seek you God if I do not remember you?”—it thus begins as a present memory of his past (infancy) in which he tries to remember in his life that which he had forgotten—God.

In the mystical tradition, Augustine will reveal that the self is essentially a relation to God: the more we delve into the self, the closer we come to God. Thus, his reflection upon his life is movement towards God. Autobiography is a form necessarily situated within time through memory, whose material is one’s ontic existence.

“Oh, in the name of all your mercies, O Lord my God, tell me what you are to me!

Say into my soul: I am thy salvation. Speak so that I can hear.

See, Lord, the ears of my heart are in front of you. Do not hide your face from me.

Let me die, lest I should die indeed; only let me see your face.”

—Saint Augustine, Confessions, Bk. I, Ch.5.

4) Textual Analysis of Augustine's Confessions

Book I: Infancy and childhood

Chapters 1 - 5:

The Confessions begins: “How can I seek you God if I do not remember you?” Incessant questions—it thus begins as a present memory of his past (infancy) in which he tries to remember in his life that which he had forgotten—God.

The incessant questions: Note how these focus upon the quest to know God. They invoke the dilemma of the interplay of faith and reason:

They also beseech God for His permission to seek Him by seeking knowledge:

Chapters two and three invoke the Neoplatonist emanation theory –recall this from our discussions of Boethius--it is the idea of creation being a procession or a pouring forth or overflowing of/from God of all things into creation and is then followed cyclically with a desire in all things to return back (reversion) to one’s source. The text reveals this through the questioning of how all is from God, and thus in Him, and how He is in all things, as creator (i.e., all in God and God in all things—note, however, that this avoids pantheism because God is also transcendent of all things). The text also reveals this theory in its language and imagery in chapter three: “filled them,” “pour that surplus of yourself,” “contain all things and it is by containing things that you fill them,” “vessels,” “poured out over us,” “scattered … brought together,” “fill everything,” etc. The most common image of emanation is the cycle of water, pouring down and evaporating back up to the source.

These chapters also invoke the Neoplatonist inheritance of mereology –again, recall Boethius discussions—mereology is the study of parts and wholes, which we see through the questioning of the one and the many. We see this in the text through questions of God being wholly present in all things or partially in all things, and if all things are in Him wholly or partially: “Or can we say that, because all things together are unable to contain you wholly, therefore each thing contains only a part of you? Does everything contain the same part? Or are there different parts …” (I, 3).

Chapter four then asks “what” is God, and reveals an intense delineation of His attributes. Note that this follows logically from discussions of mereology because there will be debate if the attributes are parts of God, or if these parts can also be considered His whole, even if inadequate to encompass all that He is. These questions are crucial because these different attributes can clearly contradict or limit one another; thus, understanding how they are what God is is crucial to understanding God, and thus being able to pay homage to him through faith. Also notice in this delineation of attributes that Augustine does not permit God any of the lacks of attributes, for example, “You love, but with no storm of passion; you are jealous, but with no anxious fear …” (I, 4). Thus, He has everything in Him, since everything is of/from Him, yet not in a corrupt way or as a privation.

Notice herein, too, the consideration of “speaking.” He asks, “What does any man succeed in saying when he attempts to speak of you? Yet woe to those who do not speak of you at all, when those who speak most say nothing” (I, 4). These questions are also critical to his work, since it is his “confession.” He is speaking/writing himself to God. To confess, confessus, comes from the Latin past participle of confiteri, to acknowledge, and can be understood as a pubic pronouncement of faith or an admission of guilt where the latter can be religious or civil. [Confiteri is from com-, together, and fatus, the past participle of fateri, to admit (fari, to say or to speak), thus we see the connection between speaking and confessing.] But, we can see this text is about much more than a mere delineation of his wrongs.

Book II, Ch. 3 has a further comment about why and to whom he is writing: “But to whom am I relating this? Not to you, my God. But I am telling these things un your presence to my own kind …. And my object in doing so is simply this: that both I myself and whoever reads what I have written may think out of what depths we are to cry unto Thee. For nothing comes nearer to your ears than a confessing heart and a life of faith” (II, 3). (X, 2 has further passages on the question of to whom and why.)

So, the Confessions is addressed dually: to God and to witnesses. But, why confess to an omniscient God? He knows without you giving testimony, for you are testimony in your being insofar as He is your creator. One is one’s confession: “testimony” is from the Latin testimonium, evidence or proof, where testis is witness and monium signifies an action, condition, or state of being (the term is implicitly religious, it initially designated the Ten Commandments).

It is further peculiar that Augustine is confessing because his Confessions reveals him as a seeker readily pronouncing ignorance:

Finally, note how chapter five takes on a very desperate tone, almost a bit presumptuous: “Oh, that you would come into my heart and so inebriate it that I would forget my own evils …” (I, 5); “What are you to me? Have mercy on me that I may speak. What am I to you that you should demand to be loved by me?” (I, 5); “Oh, in the name of all your mercies, O Lord my God, tell me what you are to me! Say into my soul: I am thy salvation. Speak so that I can hear. See, Lord, the ears of my heart are in front of you. Do not hide your face from me. Let me die, lest I should die indeed; only let me see your face” (I, 5); and “It is in a state of collapse; will you not rebuild it?” (I, 5). Here, we sense that Augustine, in his love for God, is being a rather tempestuous lover, and rather demanding.

Chapters 6 –7:

Infancy. Innocent errors of children should be corrected. His mistake was that he paid attention to God’s creatures and not to God.

Chapter six gives us a wonderful genealogy of knowledge: he came into the world (via mother and via God) knowing only “… how to suck, to be content with bodily pleasure, and to be discontented with bodily pain; that was all” (I, 6). Then, began to smile, then to become conscious, then desired to express himself, which he did through his “limited forms of communication,” since his whole desire hinged upon making his “feelings intelligible to others” (I, 6). (This genealogy continues in chapter eight.)

Chapters 8-16:

Schooling. Not like lessons. Not like Greek, liked Latin. He approves of grammar more than of literature (Homer) where immoral people are given divine attributes and this hides their vice. (ch.9, knots of language). (ch. 11 baptism).

Chapter eight continues the genealogy of knowledge by relating how he learned to speak. This chapter was quite influential on developmental models and the philosophy of language, and perhaps most famous as its citation and sharpest critique by Wittgenstein in the beginning of his Philosophical Investigations (also critiqued in de Saussure’s theory of the arbitrariness of the sign). Essentially, Augustine argues that he learned language through his own use of reason (given him by God), but having the pre-existing inner feelings that he desired to express in an intelligible manner; thus, he observed how adults communicated and slowly learned that the words they said corresponded to things in the world; he then practiced making these sounds, and was, finally, then able to speak.

These chapters also lay out, at length, the varieties of his sins, thus, most closely representing a true confession.

Chapter 11 reveals that his mother had “marked [him] with the sign of the Lord’s cross” when he was born and he goes on to wonder about youth or adult baptism, questioning why baptism should be delayed, and if this does not just offer one free rein within which to sin before commitment to God.

We also learn a lot about his love of Latin literature and his dislike for Greek and other studies. His criticism against school teachers and the literati is intense; it is also curious that he so dismisses rhetoric (which he gave up before his conversion), yet his work is beautifully written and relies on a number of persuasive tactics (see below).

Chapters 16 –20:

Language, Words. Words are signs of things and we are prompted to learn how to speak so that our will will be obeyed. Doing good involves doing it willingly and not accidentally.

These remaining chapters have the clearest condemnation of the persuasive power of words, as he expresses it, speaking hyperbolically for schools, “This is where you can learn words. This is where you can learn that art of eloquence which is so essential for gaining your own ends and for expressing your own opinions” (I, 16). Again, I wonder why the intensity—he was a rhetor early, and while he gave it up before his conversion, he was made priest and then bishop, he gave many, many sermons, and he wrote this text, clearly saying it is both for God and for other witnesses who may read it and benefit from it. The Confessions is a persuasive and artfully crafted work. Do we wonder, then, if his dismissal should be read a little like Socrates’, who proclaimed, in the Apology, that the lie he was most offended at was that Meletus, et al, accused him of being a crafty or clever speaker, and that he was not, but would speak in his everyday style …? Is there an irony, then, for dismissing the persuasive power of speech? And, does this also, perhaps, reflect upon that interplay of faith and reason? On which side would we put persuasion? (Recall, also, a similar discussion we had with Boethius about the dismissal of the muses of poetry by the muse of Philosophy—who still used poetry!)

Chapters 1 - 5:

The Confessions begins: “How can I seek you God if I do not remember you?” Incessant questions—it thus begins as a present memory of his past (infancy) in which he tries to remember in his life that which he had forgotten—God.

The incessant questions: Note how these focus upon the quest to know God. They invoke the dilemma of the interplay of faith and reason:

- “For how can one pray to you unless one knows you? If one does not know your, one may pray not to you, but to something else. Or is it rather the case that we should pray to you in order that we may come to know you?” (I, 1).

- “And how shall I pray to my God …” (I, 2) and “How can I call you when I am already in you” (Ibid.).

- “What, then, is my God?” (I, 4).

- —which unleashes a delineation of His attributes (e.g., highest, best, all-powerful, merciful, just, etc.).

They also beseech God for His permission to seek Him by seeking knowledge:

- “Let me seek you, Lord, by praying to you and let me pray believing in you; since to us you have been preached” (I, 1)—which suggests seeking by demonstration of faith, but the seeking is done in knowing.

Chapters two and three invoke the Neoplatonist emanation theory –recall this from our discussions of Boethius--it is the idea of creation being a procession or a pouring forth or overflowing of/from God of all things into creation and is then followed cyclically with a desire in all things to return back (reversion) to one’s source. The text reveals this through the questioning of how all is from God, and thus in Him, and how He is in all things, as creator (i.e., all in God and God in all things—note, however, that this avoids pantheism because God is also transcendent of all things). The text also reveals this theory in its language and imagery in chapter three: “filled them,” “pour that surplus of yourself,” “contain all things and it is by containing things that you fill them,” “vessels,” “poured out over us,” “scattered … brought together,” “fill everything,” etc. The most common image of emanation is the cycle of water, pouring down and evaporating back up to the source.

These chapters also invoke the Neoplatonist inheritance of mereology –again, recall Boethius discussions—mereology is the study of parts and wholes, which we see through the questioning of the one and the many. We see this in the text through questions of God being wholly present in all things or partially in all things, and if all things are in Him wholly or partially: “Or can we say that, because all things together are unable to contain you wholly, therefore each thing contains only a part of you? Does everything contain the same part? Or are there different parts …” (I, 3).

Chapter four then asks “what” is God, and reveals an intense delineation of His attributes. Note that this follows logically from discussions of mereology because there will be debate if the attributes are parts of God, or if these parts can also be considered His whole, even if inadequate to encompass all that He is. These questions are crucial because these different attributes can clearly contradict or limit one another; thus, understanding how they are what God is is crucial to understanding God, and thus being able to pay homage to him through faith. Also notice in this delineation of attributes that Augustine does not permit God any of the lacks of attributes, for example, “You love, but with no storm of passion; you are jealous, but with no anxious fear …” (I, 4). Thus, He has everything in Him, since everything is of/from Him, yet not in a corrupt way or as a privation.

Notice herein, too, the consideration of “speaking.” He asks, “What does any man succeed in saying when he attempts to speak of you? Yet woe to those who do not speak of you at all, when those who speak most say nothing” (I, 4). These questions are also critical to his work, since it is his “confession.” He is speaking/writing himself to God. To confess, confessus, comes from the Latin past participle of confiteri, to acknowledge, and can be understood as a pubic pronouncement of faith or an admission of guilt where the latter can be religious or civil. [Confiteri is from com-, together, and fatus, the past participle of fateri, to admit (fari, to say or to speak), thus we see the connection between speaking and confessing.] But, we can see this text is about much more than a mere delineation of his wrongs.

Book II, Ch. 3 has a further comment about why and to whom he is writing: “But to whom am I relating this? Not to you, my God. But I am telling these things un your presence to my own kind …. And my object in doing so is simply this: that both I myself and whoever reads what I have written may think out of what depths we are to cry unto Thee. For nothing comes nearer to your ears than a confessing heart and a life of faith” (II, 3). (X, 2 has further passages on the question of to whom and why.)

So, the Confessions is addressed dually: to God and to witnesses. But, why confess to an omniscient God? He knows without you giving testimony, for you are testimony in your being insofar as He is your creator. One is one’s confession: “testimony” is from the Latin testimonium, evidence or proof, where testis is witness and monium signifies an action, condition, or state of being (the term is implicitly religious, it initially designated the Ten Commandments).

It is further peculiar that Augustine is confessing because his Confessions reveals him as a seeker readily pronouncing ignorance:

- “Let me know you, my known, let me know Thee even as I am known” (X, 1),

- and “how shall I find you if I do not remember you” (X, 17),

- and “how can one pray to you unless one knows you” (I, 1)?

Finally, note how chapter five takes on a very desperate tone, almost a bit presumptuous: “Oh, that you would come into my heart and so inebriate it that I would forget my own evils …” (I, 5); “What are you to me? Have mercy on me that I may speak. What am I to you that you should demand to be loved by me?” (I, 5); “Oh, in the name of all your mercies, O Lord my God, tell me what you are to me! Say into my soul: I am thy salvation. Speak so that I can hear. See, Lord, the ears of my heart are in front of you. Do not hide your face from me. Let me die, lest I should die indeed; only let me see your face” (I, 5); and “It is in a state of collapse; will you not rebuild it?” (I, 5). Here, we sense that Augustine, in his love for God, is being a rather tempestuous lover, and rather demanding.

Chapters 6 –7:

Infancy. Innocent errors of children should be corrected. His mistake was that he paid attention to God’s creatures and not to God.

Chapter six gives us a wonderful genealogy of knowledge: he came into the world (via mother and via God) knowing only “… how to suck, to be content with bodily pleasure, and to be discontented with bodily pain; that was all” (I, 6). Then, began to smile, then to become conscious, then desired to express himself, which he did through his “limited forms of communication,” since his whole desire hinged upon making his “feelings intelligible to others” (I, 6). (This genealogy continues in chapter eight.)

Chapters 8-16:

Schooling. Not like lessons. Not like Greek, liked Latin. He approves of grammar more than of literature (Homer) where immoral people are given divine attributes and this hides their vice. (ch.9, knots of language). (ch. 11 baptism).

Chapter eight continues the genealogy of knowledge by relating how he learned to speak. This chapter was quite influential on developmental models and the philosophy of language, and perhaps most famous as its citation and sharpest critique by Wittgenstein in the beginning of his Philosophical Investigations (also critiqued in de Saussure’s theory of the arbitrariness of the sign). Essentially, Augustine argues that he learned language through his own use of reason (given him by God), but having the pre-existing inner feelings that he desired to express in an intelligible manner; thus, he observed how adults communicated and slowly learned that the words they said corresponded to things in the world; he then practiced making these sounds, and was, finally, then able to speak.

These chapters also lay out, at length, the varieties of his sins, thus, most closely representing a true confession.

Chapter 11 reveals that his mother had “marked [him] with the sign of the Lord’s cross” when he was born and he goes on to wonder about youth or adult baptism, questioning why baptism should be delayed, and if this does not just offer one free rein within which to sin before commitment to God.

We also learn a lot about his love of Latin literature and his dislike for Greek and other studies. His criticism against school teachers and the literati is intense; it is also curious that he so dismisses rhetoric (which he gave up before his conversion), yet his work is beautifully written and relies on a number of persuasive tactics (see below).

Chapters 16 –20:

Language, Words. Words are signs of things and we are prompted to learn how to speak so that our will will be obeyed. Doing good involves doing it willingly and not accidentally.

These remaining chapters have the clearest condemnation of the persuasive power of words, as he expresses it, speaking hyperbolically for schools, “This is where you can learn words. This is where you can learn that art of eloquence which is so essential for gaining your own ends and for expressing your own opinions” (I, 16). Again, I wonder why the intensity—he was a rhetor early, and while he gave it up before his conversion, he was made priest and then bishop, he gave many, many sermons, and he wrote this text, clearly saying it is both for God and for other witnesses who may read it and benefit from it. The Confessions is a persuasive and artfully crafted work. Do we wonder, then, if his dismissal should be read a little like Socrates’, who proclaimed, in the Apology, that the lie he was most offended at was that Meletus, et al, accused him of being a crafty or clever speaker, and that he was not, but would speak in his everyday style …? Is there an irony, then, for dismissing the persuasive power of speech? And, does this also, perhaps, reflect upon that interplay of faith and reason? On which side would we put persuasion? (Recall, also, a similar discussion we had with Boethius about the dismissal of the muses of poetry by the muse of Philosophy—who still used poetry!)

Confessions, Book II, age 16

Overview Bk. II: Age 16 in Thagaste with ‘debased’ boys—stole pears and fed them to pigs. Committed theft out of no need or enjoyment of the things themselves (pears not attractive in appearance or taste).

Chapter 1 - 3:

He begins by saying that he wants to recall his “past impurities,” not because he is proud of them, but to confess them out of his love of God (1). His past impurities consisted in loving and being loved in the sense of the “muddy cravings of the flesh;” his lust is awakened, and beneath the flowered prose, we can assume that he discovered the fairer sex through fornication (some may well argue that is was not really pears that the young boys stole) (2-3). Augustine is back in his hometown of Thagaste (from Madaura and before going to Carthage) and befriends a group of ‘debased’ boys (3). He confesses that he sought their approval and love instead of God’s. He bemoans his family for not having married him off to keep him from such lust (2) and demands why did God remain silent while his lust took him further and further from God (3)? Although, he does admit that now he sees his mother’s warnings to have been the command of God coming through his mother (3).

Chapter 4-10:

The pear tree was in a neighbor’s yard, and their theft was a forbidden act. The young boys stole the fruits, not to eat, but just to steal them, ultimately feeding them to some pigs. They committed the theft out of no need or enjoyment of the things themselves, as the pears were not attractive in appearance or taste, which leads the ashamed, adult Augustine to struggle to come to a definition of sin, so as to be able to explain why he sinned.

In Book II, Augustine raises at least seven possible reasons for why he sinned:

“and yet I still could not understand clearly and distinctly what was the cause of evil” (VII.3)

“But I still asked: ‘What is the origin of evil?” (VII.7):

For Comparison, Consider EVIL for Socrates and Aristotle:

Overview Bk. II: Age 16 in Thagaste with ‘debased’ boys—stole pears and fed them to pigs. Committed theft out of no need or enjoyment of the things themselves (pears not attractive in appearance or taste).

Chapter 1 - 3:

He begins by saying that he wants to recall his “past impurities,” not because he is proud of them, but to confess them out of his love of God (1). His past impurities consisted in loving and being loved in the sense of the “muddy cravings of the flesh;” his lust is awakened, and beneath the flowered prose, we can assume that he discovered the fairer sex through fornication (some may well argue that is was not really pears that the young boys stole) (2-3). Augustine is back in his hometown of Thagaste (from Madaura and before going to Carthage) and befriends a group of ‘debased’ boys (3). He confesses that he sought their approval and love instead of God’s. He bemoans his family for not having married him off to keep him from such lust (2) and demands why did God remain silent while his lust took him further and further from God (3)? Although, he does admit that now he sees his mother’s warnings to have been the command of God coming through his mother (3).

Chapter 4-10:

The pear tree was in a neighbor’s yard, and their theft was a forbidden act. The young boys stole the fruits, not to eat, but just to steal them, ultimately feeding them to some pigs. They committed the theft out of no need or enjoyment of the things themselves, as the pears were not attractive in appearance or taste, which leads the ashamed, adult Augustine to struggle to come to a definition of sin, so as to be able to explain why he sinned.

In Book II, Augustine raises at least seven possible reasons for why he sinned:

- 1) Out of need or enjoyment of the things themselves (“I had no wish to enjoy what I tried to get by theft” (II.4); “all I tasted in them was my own iniquity” (II.6).).

- 2) Due to a lack or despise of a proper feeling or presence of an improper feeling (“I lacked and despised proper feeling and was stuffed with iniquity” (II.4); “all I tasted in them was my own iniquity” (II.6).)

- 3) Sin to enjoy the act of sin (no reason for it: “The evil was foul, and I loved it; I loved destroying myself; I loved my sin …” (II.4); “I only took these ones in order that I might be a thief” (II.6); “loved crime for crime’s sake” (II.7); “love nothing except the theft itself” (II.8). The hardest to fathom (re: II.5, 6).)

- 4) Sin to attain an end (a lower good) or avoid losing something (immoderate liking for material things—“desire for gaining or a fear of losing some of these goods we have described as ‘lower’” (II.5)—as a turning away from eternal things; “Yet for all these things … sin is committed. For there are goods of the lowest order, & we sin if, while following them with too great an affection, we neglect those goods which are better & higher …” (II.5).)

- 5) Sin to imitate acts found only in God (seek to imitate God’s omnipotence: “did I imitate my Lord?… producing a darkened image of omnipotence?” (II.6)—thereby perverting it; e.g., pride imitates loftiness of mind, ambition seeks honor, wanton sexuality imitates love, curiosity imitates desire for knowledge.)

- 6) Sin to enjoy the crime and association (if he was alone he would not have done it: “friendship, knotted in affection, is a sweet thing …” (II.5); “a pleasure occasioned by the company of others who were sinning with me” (II.8); “nor would I have got any pleasure out of it by myself, nor would I have done it by myself” (II.9)).

- 7) Cannot be known; doesn’t truly understand his own sins (“Who can disentangle this most twisted and most inextricable knottiness?” (II.10)). (Is this proposing a Platonic account of evil caused by ignorance? Augustine seems to favor an Aristotelian akrasia—one can know X is evil, but still desire to and do it.)

“and yet I still could not understand clearly and distinctly what was the cause of evil” (VII.3)

“But I still asked: ‘What is the origin of evil?” (VII.7):

- “free will is the cause of our doing evil and your just judgment the cause of our suffering it” (VII.3).

- --“act of willing was mine … here was the cause of my sin” (VII.3)

- --but, “things which I did unwillingly … I was suffering rather than doing … such things to be my punishment … you as just…I was not being punished unjustly. But then I asked: ‘Who made me? Was it not my God,…goodness itself? How then could it be that I should will evil and refuse my assent to good, so that it would be just for me to be punished?” (VII.3).

- “If the devil is responsible, then where did the devil come from?” (VII.3).

- “the incorruptible was better than the corruptible” (VII.4).

- “I searched for the origin of evil and I searched for it in an evil way … I put the whole creation in front of the eyes of my spirit …” (VII.5).

- --“Where, then, is evil? Where did it come from and how did it creep in here? What is its root and seed? Or does it simply not exist?” (VII.5).

- –“where:” substances occupy space; “creep:” “[heathens]shall lick dust as a serpent; as creeping things of earth they shall be disturbed, or troubled, [out] of their houses; they shall not desire our Lord God” (Micah 7:17); “root and seed:” dormant potential, perhaps unforeseen—“was there some evil element in the material of creation, & did God shape & form it, yet still leave in it something … He did not change into good?” (VII5).

- --“Where, then, is evil? Where did it come from and how did it creep in here? What is its root and seed? Or does it simply not exist?” (VII.5).

- God: “I am that I am” vs. “other things … neither are nor are not in existence” (VII.10-11).

- --“things which are subject to corruption are good. They would not be subject to corruption if they were either supremely good or not good at all: for, if they were supremely good, they would be incorruptible, and, if there was nothing good in them, there would be nothing which could be corrupted” (VII.12).

- --“all things which suffer corruption are deprived of something good in them” (VII.12).

- --“Therefore, so long as they exist, they are good. Therefore all things that are, are good, and as to that evil … it is not a substance, since if it were a substance, it would be good” (VII.12).

- “To you then, there is no such thing at all as evil. And the same is true … [for] your whole creation” (VII.13).

- –“But in some of its parts there are some things which are considered evil because they do not harmonize with other parts; yet with still other parts they do harmonize and are good and they are good in themselves. And all these things which do not fit in with each other do fit in with that lower part of creation which we call the earth” (VII.13: God’s eye view)

- “‘What is wickedness?’ … it is not a substance but a perversity of the will turning away from you, God … toward lower things—casting away, as it were, its own insides and swelling with desire for what is outside it” (VII.16).

- –Genealogy of knowledge/Ladder of judgments (VII.17) describes making correct judgments re: evil, but also model for ordering the self and, hence, to keep from evil.

For Comparison, Consider EVIL for Socrates and Aristotle:

- Evil for Socrates:

- Socrates proposes that Virtue is Knowledge; for him to be able to hold this position, one has to understand the nature of virtue’s opposite: vice is ignorance.

- By our being essentially knowing beings, our natures, then, are naturally virtuous. Naturally virtuous, we do not naturally desire evil. And, if virtue is knowledge, than evil, its opposite, cannot be knowledge, it must be ignorance. So, if it is not known, one cannot knowingly choose it. In other words, beneath the claim that virtue is knowledge are two premises:

- (1) No one desires evil — what we want is the good, if we do desire evil, it is b/c we think it is good.

- (2) No one deliberately does evil — they are just ignorant of what the good really is.

- Evil for Aristotle:

- Aristotle rejects Plato’s idea that we can never knowingly desire evil. This becomes apparent in his explanation of Akrasia (incontinence, or the lack of virtue) in his Nicomachean Ethics, in which all character virtues are the means between two extremes, for example, the virtue of courage is that which is neither cowardice nor foolhardiness. These extremes are vices. However, he has a category of wrong that is not vice, but neither is it virtue: Akrasia. This is the conflict born from the desire for pleasure that has the power to overcome our reasoning about the right choice. So, this lack of virtue that is not wholly vice is a passionate power that overwhelms the mind and makes us do evil even when we know it is not the good.

- So, Akrasia, incontinence, is the weakness of will. This is not ignorance of the good; rather, it is ignoring the good: I may know that eating fifteen cherry pies is the vice of overindulgence, and that it is better to only eat one slice, yet, I choose to eat all fifteen pies anyway.

- Is either of these models closest to why Augustine may have sinned?

- - - The Intervening Books: III to VI - - -

Book III: Later Youth

Augustine becomes skilled at rhetoric, generating a great vanity in the young man. He was notably influenced by Cicero’s Hortensius, which sparked his interest in philosophy and may be considered his first “conversion,” and intellectual one.

This conversion inspires his desire of wisdom over the pleasures of the senses. He was impressed by the content and rhetoric of the Hortensius but something…he later identifies as the name of Christ--was missing. Scripture seemed unworthy to him so he turned to Manichaeism: this is his second “conversion:”

The adult Augustine decides that the Manicheans spoke of Christ and Holy Spirit but it was not in their hearts; they searched for God through the senses instead of intellectual understanding.

Book IV: Augustine as a Manichean (from 19 to 28).

He taught rhetoric for lawyers and had a child. Reads Aristotle’s Categories and he included God under the categories. He tries to understand God as a body.

Book V: Rome and Milan (age 29 and up).

The attempt to find oneself can help one to find God.

Begins to doubt Astronomy/Astrology; they may speak truthfully about creatures, but not about God. Yet, astronomical truths established mathematically contradicted some of Mani’s teachings and force Mani to declare natural science sacrilegious in the face of disagreement. This begins to spark doubt in Manichaeism; this is further ignited when Faustus, said to be a very wise Manichee, was unable to answer any of his questions about its relation to natural science. A further point of doubt was about the lack of ethical responsibility born from their theory of sin, which was due to some different nature within us.

Augustine leaves Cartage and goes to Rome.

At this point he comes across the Skeptics of the Academy and they seem to him to be the wisest of all.

Meets St. Ambrose; was impressed by his content on God, but not his style. Ambrose instructed him to interpret the Bible metaphorically, that evil as a privation and not a substance, and that there is free will (deliberately doing evil). While he saw that the Catholic faith could be defended against Manicheanism, and this is enough to make him leave the Manichean position, he is not ready to convert to Christianity. It takes Augustine many more books before he is able to understand and accept these lessons.

Book VI: Years of Struggle.

Book III: Later Youth

Augustine becomes skilled at rhetoric, generating a great vanity in the young man. He was notably influenced by Cicero’s Hortensius, which sparked his interest in philosophy and may be considered his first “conversion,” and intellectual one.

This conversion inspires his desire of wisdom over the pleasures of the senses. He was impressed by the content and rhetoric of the Hortensius but something…he later identifies as the name of Christ--was missing. Scripture seemed unworthy to him so he turned to Manichaeism: this is his second “conversion:”

- Manichaeism:

- was a dominating and wide-spread, organized religion between, approximately, the 3rd and 16th centuries. It was founded by the Babylonian prophet Mani (ca. 210-276 ce, within the Persian empire), who composed arguably six to eight sacred texts, of which only fragments survive, said to be the complete teachings only partially revealed by the Buddha, Jesus, and Zoroaster (who promoted a similar dualism between truth and lie, albeit not a cosmological explanation, and whose priesthood was said to have put Mani to death ca. 276). The main character of the religion was its dualism; his central tenet posited two contrasting forces, light and dark, which roughly correspond to good and evil, peace and violence, and spirit and matter. All things are a combination of these elements, so there is no fully omnipotent God. Humanity, as the preeminent combination of the corruptible and incorruptible (body and soul), is the central ground where these forces do battle and can overcome the darkness by complete union with the incorruptible aspect.

The adult Augustine decides that the Manicheans spoke of Christ and Holy Spirit but it was not in their hearts; they searched for God through the senses instead of intellectual understanding.

Book IV: Augustine as a Manichean (from 19 to 28).

He taught rhetoric for lawyers and had a child. Reads Aristotle’s Categories and he included God under the categories. He tries to understand God as a body.

Book V: Rome and Milan (age 29 and up).

The attempt to find oneself can help one to find God.

Begins to doubt Astronomy/Astrology; they may speak truthfully about creatures, but not about God. Yet, astronomical truths established mathematically contradicted some of Mani’s teachings and force Mani to declare natural science sacrilegious in the face of disagreement. This begins to spark doubt in Manichaeism; this is further ignited when Faustus, said to be a very wise Manichee, was unable to answer any of his questions about its relation to natural science. A further point of doubt was about the lack of ethical responsibility born from their theory of sin, which was due to some different nature within us.

Augustine leaves Cartage and goes to Rome.

At this point he comes across the Skeptics of the Academy and they seem to him to be the wisest of all.

Meets St. Ambrose; was impressed by his content on God, but not his style. Ambrose instructed him to interpret the Bible metaphorically, that evil as a privation and not a substance, and that there is free will (deliberately doing evil). While he saw that the Catholic faith could be defended against Manicheanism, and this is enough to make him leave the Manichean position, he is not ready to convert to Christianity. It takes Augustine many more books before he is able to understand and accept these lessons.

Book VI: Years of Struggle.

Lions, from a medieval bestiary

Lions, from a medieval bestiary

Augustine’s inability to understand how God as spirit could not be corporeal if man was made in his image converts him to skepticism. He wants to be certain of invisible and immaterial things as he was certain of mathematics. The adult Augustine explains that faith is necessary for reason and knowledge, and that he did not yet have any.

He wants joy in truth. He still clings to worldly honors. Thinks about monastic life. His wife leaves and leaves his son with him, he gets another woman. He abandons carnal pleasures due to fear of God’s judgment. He opposes Epicurean hedonism which makes sense only if there is no afterlife and judgment.

He wants joy in truth. He still clings to worldly honors. Thinks about monastic life. His wife leaves and leaves his son with him, he gets another woman. He abandons carnal pleasures due to fear of God’s judgment. He opposes Epicurean hedonism which makes sense only if there is no afterlife and judgment.

Book VII: Growing to Manhood: Preamble to his Conversion. --Incorporeality & Evil--

Chapter 1:

Growing into manhood, the problem that plagued Augustine, and kept him from converting to Christianity, was understanding the nature of God as noncorporeal: “I was unable to form an idea of any kind of substance other than what my eyes are accustomed to see” (p.124).

He understood, rationally, that God had to be incorporeal because had he matter, he would be subject to corruption; but, he found himself unable to conceive of God as noncorporeal … how can God, which is, exists, thus, exists as some thing, be nothing and yet be (p.124-5)? So, he figured, that the whole world must be finite and God, in infinity, is infused throughout all that is (which is arguably either pantheism—all that is, is God—or pandeism—God is before creation, cause of creation and its creator, and is all that is); he knew that this was error, and posed the logical argument that if it were the case, than the elephant would be more perfect than the sparrow because the elephant has more of God within it, and that this is an absurd argument, yet he could not overcome the material-ness of God (126). Nb.: ‘corruptibility’: Aristotelian theme; ‘sun,’ ‘enlightened’: Platonic imagery.

Chapter 2: finally breaks from Manichees

- Argument against Manichaeism (posed first by Nebridius, his close friend from Carthage and Milan):

- Manichees pose darkness in an eternal fight against light; but, what would the darkness do if the light refused to fight? Well, the dark would do the light harm, then. But, then the light would suffer injury and corruption; and violate the premise that it is the pure side, incorruptible. So, if the dark would not do the light harm, than why would the fighting have continued eternally? The light is to be all-knowing as well, and should have known this, stop fighting, and then be all-powerful in the resultant peace.

Chapter 3:

Yet, he still could not convert to Christianity. His dominant block was the cause of evil.

The adult Augustine offers a definition that he will eventually adopt at the bottom of p.127:

“…free will is the cause of our doing evil and your just judgment is the cause of our suffering it…” (127). In addition, he acknowledges that his will is entirely his own. But, he ‘knows’ this without, yet, understanding it.

Chapter 4:

Reason alone had taught him that the incorruptible is better than the corruptible, and he needed to find the reason that would show him the cause of evil. He came to the conclusion that the incorruptible was better because no one can conceive of anything more supreme and more good than God and the same for the incorruptible, so God must be incorruptible.

Chapter 5:

“I searched for the origin of evil and I searched for it in an evil way, and I did not see the evil in the very method of my search” (p.129)--because he conceived of everything as things, as bodies. And even the lowliest bodies are good, as they are created by God, so where did evil come from?

Chapter 6:

He breaks his belief in astronomy/astrology: He hears a story from Firminus (who did believe) about his father and his friend who were ardent believes in astrology who kept meticulous records about events and the stars, including records about one’s wife and one’s slave who conceived children at the exact same moment and gave birth at the exact same moment, thus, both children had identical horoscopes. But, one child, of high birth, achieved a good life while the slave child could not. Thus, their horoscopes could not both be the same and both be right (132-5).

Note that Augustine’s final reason for splitting from Astrology is born from reason.

Chapter 7:

So, he still searches for the origin of evil. “And you were listening, though I did not know it. When in silence I strongly urged my question, the quiet contrition of my soul was a great cry to your mercy” (135).

“How could they [his friends] hear the tumult of my soul when I had neither time nor language sufficient to express it?” (135): Augustine felt what he could not say but he could not yet believe what he could not express through reason.

Chapter 8:

God’s not angry for his questioning.

Chapter 9:

Augustine discovers Neo-Platonism. He found all the truths about God that he had come to learn in the philosophy, but found nothing about Jesus.

“Thus hiddest these things from the wise, and revealedst them to babes…” (138).

Through what was missing from the philosophy, Augustine was able to move towards an embrace of God.

Chapter 10:

“I was admonished by all this to return to my own self, and, with you to guide me, I entered into the innermost part of myself, and I was able to do this because you were my helper” (139). True to Plato, philosophy is effective if it provokes the self to take it up unto oneself… and recall, for Augustine, that the self is essentially a relation to God: the more we delve into the self, the closer we come to God. This movement was inspired by philosophy.

Note: Chapters 10-16 address the topic of evil ... 10 & 11 also directly address the existential distinction of existence and essence: within 10, there is the divine equation (I am that I am) with existence as essence and vice versus, whereas chapter 11 is the human distinction (Other things neither are nor are not) with existence not equalling essence.

Chapter 11:

God is highest reality.

Chapter 12:

The corruptible: even the corruptible is good; it is not supremely good b/c it is not God, but it is not not good b/c then it would not be b/c God does not create not-good things ... So … God made all things very good. This linkage of corruption to deprivation shows the idea of 'proportionate privation' wherein if something is, it is good to some degree.

Chapter 13:

“To you, then, there is no such thing at all as evil. And the same is true not only of you but of your whole creation; since there is nothing outside it to break in and corrupt the order which you have imposed upon it” (p.141). There is no such thing as evil. Note: the importance of hierarchy herein.

Chapter 14:

Manicheanism had posited two substances in order to understand good and evil. Augustine realizes this was his madness and sickness believing it.

Chapter 15:

Everything is from you, God, not any other source. This chapter shows the equation of 'Existence = good = true.' Its argumentation also uses the idea of material falsity, that 'X is' when it is not.

Chapter 16:

Definition of EVIL:

- “And I asked: ‘What is wickedness?’ and found that it is not a substance but a perversity of the will turning away from you, God, the supreme substance, towards lower things—casting away, as it were, its own insides and swelling with desire for what is outside it” (143).

Chapter 17:

Augustine loved and believed in God, “But I did not stay in the enjoyment of my God; I was swept away to you by your own beauty, and then I was torn away from you by my own weight and fell back groaning toward these lower things. Carnal habit was this weight” (p.143). The carnal is libido / lust / eros, all 'lack'.

How judgments are made, i.e., how knowledge is and how it leads to his knowledge gained of God:

- Compare this to Plato's 'ladder of love' (Symposium): like Plato’s forms, Augustine realizes there is an unchangeable realm above the changeable world here around us. In this world, there are bodies that perceive by bodily senses; these senses send along perceptions of the external world to the inner power of the soul that, through the faculty of reason, discerns them so as to create a judgment. (i.e., compare the ladder of love to the genealogy of knowledge he develops in I.6, 8.)

Augustine finds that he has raised himself beyond habit to understanding to form a perfect judgment of the truth of the unchangeable realm: “in the flash of a trembling glance, my mind arrived at That Which Is” (144).

But, he could not keep his eye trained to this knowledge.

Chapter 18:

Doesn’t have the strength to fully convert.

Chapter 19:

Still doesn’t understand Jesus as more than man. Reveals that he still sees the Scriptures as literal. Note: his portrait of Jesus as role model re-invokes the question(s) ‘to whom and why does Augustine write?’

Chapter 20:

Further reading of the Neo-Platonists revealed to him the validity of incorporeal truth. Figures God showed him these books at this perfect time to prepare him for conversion.

Chapter 21:

Reads the Scriptures, namely, Apostle Paul. He discovers all of the truth that he had found through reason and in the Platonists in Paul plus the glorification of God, which all other truths had lacked. Shows movement to faith from faith; an ascent to “trembling.”

Book VIII: Conversion

Chapter 1:

Still bound by his need of woman--knew there were those who became eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven, but was not yet himself capable of this … (p.151).

Chapter 2:

Went to Simplicianus (father of Ambrose) and confessed his desire that kept him from conversion; told him he had read the Platonists.

Simplicianus said Platonists were good, they had the word of God therein, but other philosophers were full of fallacies.

Simplicianus conveyed the story of Victorinus—scholar, philosopher, teacher of senators—who converted to Christianity. Initially he was ashamed to go to church, demanding of Simplicianus whether entry beyond its walls made one a Christian? But, he did fear and feel shame for not publicly being Christian and feared that God would deny him. Thus, one day, he asked Simplicianus to take him along to Church and make him a Christian. He goes, publicly converts.

Chapter 3:

“O good God, what is it in men that makes them rejoice more when a soul that has been despaired of and is in very great danger is saved than when there has always been hope and the danger has been so serious?” (154-5).

The victorious general has a triumph, which necessitates that he had a battle; and the more triumphant if the more dangerous a one (155). All emotions seem more powerful when they have more adversity—a man may take women for granted until he has been made to wait, sighing, for one. Why is this God?

Chapter 4:

“… Thou hast chosen the weak things of the world, to confound the strong, and the base things of this world, and the things despised hast Thou chosen, and those things which are not, that Thou mightest bring to nought things that are” (157).

Chapter 5:

Augustine’s Psychology of the Perverse and the Spiritual Will:

- Augustine longs to give himself to religion: “This was just what I longed for myself, but I was held back, and I was held back not by fetters put on me by someone else, but by the iron bondage of my own will. The enemy held my will and made a chain out of it and bound me with it. From a perverse will came lust, and slavery to lust became a necessity. These were like links, hanging each to each (which is why I called it a chain), and they held me fast in a hard slavery” (158).

He longed for God, but this new will was not strong enough against his old will:

- Will one: spiritual

- Will two: carnal

Psychology of Perverse Will:

- Lust is made out of perverse will;

- When one becomes bound to lust, lust becomes habit;

- When lust becomes habit (habit not resisted), lust becomes necessity;

- When lust is a necessity, this is Carnal Will.

“… the flesh lusteth against the spirit and the spirit against the flesh …” (158).

Augustine’s spiritual will conflicts with his carnal will; he has as much fear of being freed from his lust as he had for being lustful.

He likens himself to someone asleep: one doesn’t want to sleep forever, yet it is so hard to awaken… he could sense God calling him to awaken, yet he, like a half-sleep person, wanted to sleep just a little longer (159).

Chapter 6:

In case we were unsure why he wanted to stay asleep, it was because of his bondage of desire for sex… oh, yeah, and fetters to the affairs of the world.

His friend Alypius and he were visited by a man named Ponticianus (from Africa); Ponticianus sees they have a copy of Paul’s writings, he admits he is a baptized Christian. He proceeded to tell them about an Egyptian monk named Antony: two men, friends of Ponticianus, came across the written account of Antony’s life and instantly converted—one paused, reading, felt ful of anxiety and fear, kept reading, and the fear and anxiety faded to peace and resoluteness—and the men dedicated their lives to God; even their fiancés, upon hearing about the men, instantly converted as well.

Chapter 7:

Augustine knew that God was speaking through Ponticianus, showing him to himself: “I could see how foul a sight I was—crooked filthy, spotted, and ulcerous” (164). But, he could still not convert: “Make me chaste and continent, but not yet” (164).

“As Ponticianus went on with his story, I was lost and overwhelmed in a terrible kind of shame” (165).

Chapter 8:

The shame boils over as they sit in the garden together: “My looks were as disordered as my mind as I turned on Alypius and cried out to him: ‘What is wrong with us? What is this which you have just heard? The unlearned rise up and take heaven by force, while we, (look at us!) with all our learning are wallowing in flesh and blood. Is it because they have gone ahead that we are ashamed to follow? And do we feel no shame at not even following at all?’” (165).

He flails about, angered, waiting to see if his will can will him to convert; his will must be resolute and sincere, not twisted like his (166).

Chapter 9:

His mind can easily will the body, but the mind cannot easily will the will to do anything.

Chapter 10:

This duality of will does not mean that humanity has two natures (good and evil). One will (one soul) will feel the same impulses.

Chapter 11:

He feels he is close; the desperate pleading of his vice became a whisper behind his back, asking how he could do without, forever… “I pray you in your mercy to keep such things from the soul of your servant. How filthy, how shameful were these things they were suggesting!” (171).

In contrast, he sees the “chaste dignity of Continence; she was calm and serene, cheerful without wantonness, and it was in truth and honor that she was enticing me to come to her without hesitation, stretching out to receive and to embrace me with those holy hands of hers…” (172).

Chapter 12:

Augustine throws himself under a fig tree and cries. Asking how long? Then, suddenly, he hears the singsong voice of a child repeating “Tolle, lege,” “take it and read it” (173). He cannot fathom this as a game, and understands that it must be a divine command, remembering Antony being led by a passage from the Gospels. So Augustine hurries back to where Alypius was still sitting, picked up the writings of Paul and opened it at random and read (Romans 13:13-14):

- Not in rioting and drunkenness, not in chambering and wantonness, not in strife and envying: but put ye on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make not provision for the flesh in concupiscence (174).

He stopped reading and told Alypius what he had gone through. Alypius told his of his own inner turmoil and asked to read the passage; he read further:

- Him that is weak in the faith, receive (174)

And he applied these words to himself and calmly and resolutely joined Augustine in conversion.

They immediately went from there to tell Monica, Augustine’s mother; this made her happy.

Book IX- The New Catholic

The converted Augustine follows God’s will instead of his own. Abandons his career as a rhetoric teacher since it is a mere selling of words. His son Adeodatus dies at 17 and Augustine is baptized at 387 at age 33. Recalls the life and death of his mother.

The converted Augustine follows God’s will instead of his own. Abandons his career as a rhetoric teacher since it is a mere selling of words. His son Adeodatus dies at 17 and Augustine is baptized at 387 at age 33. Recalls the life and death of his mother.

Confessions Book X: Memory

- Outline:

- Chs.1-5: Why confession?

- Chs.6-7: Loving and knowing

- Chs.8-9: Treasure house of memory

- Chs.10-12: Knowing and learning

- Chs.13-15: False things and feelings

- Chs.16-19: Forgetting and beyond memory

- Chs.20-24: Happy life

Chapter 1:

“Let me know you, my known, let me know Thee even as I am known” (202).

You love the truth, and coming into the truth is coming into your love; this is what I want my confessions to be, a coming into the truth by my heart and before witnesses in my writings.

Chapter 2:

But isn’t the notion of confession odd to a God who is all knowing? Then, is confession only for the confessor?