Al-Ghazzali

On Knowing Yourself and God [Alchemy of Happiness]

(I) Biographical Sketch & Background:

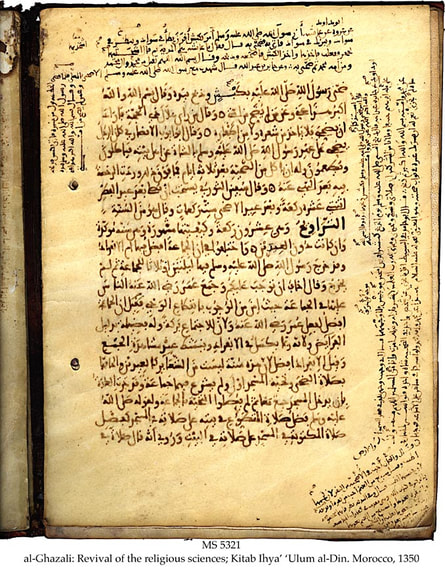

Abu Hamid Al-Ghazzali [Al-Ghazali] (ca. 1058-1111):

Born in Tabaran [a town in the district of Tus, in the province of Khorasan, in Persia], in what is now northwestern Iran, he remained there for 27 years intensely studying Islamic philosophy and religion, which led to his moving to Baghdad, where he was appointed a professor at Nizamiyyah College. His main work was in Islamic jurisprudence and had significant political connections. Four years into his position, he underwent a spiritual crisis that led to his leaving Baghdad and renouncing teaching. He felt that his knowledge was useless in comparison to gnosis, the experiential, spiritual knowledge and that the political life was not compatible with a truly virtuous religious life. To be free of worldly distractions he arranged the care of his family and set off wandering through Syria (notably Damascus), Israel/Palestine (notably Jerusalem), and Mecca. He eventually returned to his hometown of Tus, where he founded a private school and Sufi convent and remained five years before his death at 53. At his death, he left over 400 works. We remember him today as an Islamic jurist, theologian, and philosopher. He was strongly influenced by Aristotle and also a mystic in the Sufi tradition of Sunni Islam [while this may seem a disparity, the Arabic philosophy (falsafa, from the Greek philosophia, was a movement of Christian, Muslim, and pagan philosophers, later in the 12th c., including Jewish scholars) he studied was the translation of Greek philosophy and science into Arabic in the 8th to 10th c., and predominately Aristotle’s ideas expressed in Neoplatonic language (most notably, a compilation of Plotinus’ Enneads was called Theology and attributed to Aristotle)]. He immensely influenced Latin medieval philosophy—mainly on the reconciliation of reason and revelation, and through the works of Avveroes (Ibn Rushd, 1126-98) and diverse Jewish thinkers.

Links:

Sufism:

The etymology of the name sufi is uncertain, perhaps tracing back to the Arabic safa, purity, or to suf, wool, referring to the simple wool cloaks the early Islamic ascetics wore; a medieval Iranian scholar, Abu Rayhan al-Biruni, argued that the name came from the Greek sophia, wisdom. It is the mystical branch of Islam; it advocates a spiritual exercise to purify the heart and focus it on God. In addition to traditional ascetic practices, classical Sufism practiced dhikr, an activity of repeating the names of God. There are both Sunni and Shite orders of Sufism, with others being their mixture and still others claiming no allegiance to one or the other; all sects trace their original tenets back to the Prophet Mohammad (Al-Ghazali supported this view, noting the Quran as Sufism’s origin; however, some scholars argue that Sufism began before the rise of Islam and some Muslims argue that Sufism is not Islam). Sufis believe that it is possible to draw closer to God in this life, as opposed to only in Paradise after death and judgment. This is possible through embracing the divine presence, possible after conditioning oneself or restoring oneself to a primordial state (fitra, one’s condition, instinctual state, or a mystical intuitive state) of pure obedience to God obtained by pure love and purity. In this state, one has abandoned all dualistic notions and sense of self and embraced the divine unity of all. This state is attained by a stoic practice of purifying the base parts of the self and purifying the higher parts of the self, one’s heart, with contemplation of esoteric knowledge. The purification is guided by two laws, an outer law, concerning practice (civic rules), and an inner law, concerned with the heart (repentance, virtue). Beginning Sufi practice required one to find a teacher, true masters tracing their intellectual lineage back to Mohammad; the instruction is said to be by divine light to the pupil’s heart, not worldly knowledge that is transmitted from mouth to ear. Many branches of Sufism reject all book learning; Al-Ghazali scoffed at this anti-intellectualism, importantly denoting the differences between worldly knowledge and spiritual knowledge, the latter not be incommensurable with books. However, in general, Sufism encourages spiritual practice and its goal of immediate spiritual experience lends its transmission to needing poeticism and indirection, parable and metaphor.

Dhikr:

a prayer-like activity described as the remembrance of God commanded for all Muslims in the Quran that consists of repeating the names of God primarily, but may also include the repetition of the supplications and aphorism from the Quran and hadith literature (collections of sayings of the Prophet Mohammad and of acts approved of or criticized by him). It can also specify a broader state of awareness of God, a practiced consciousness of the Divine Presence and love, and the activity of attaining a state of “godwariness” (Mohammad was referred to as the embodiment of dhikr of God in the Quran). Dhikr ceremonies are called sema; these include practices of recitation, singing, music, dance, and meditation.

|

|

|

|

|

Gnosis:

Greek noun meaning “knowledge,” but the term for Al-Ghazali (and most philosophy of religion) means an intuitively experiential spiritual knowledge that is attained through interior reflection and/or mystical experience. Gnosticism is the knowledge born from religious experience; being mystical, this knowledge rarely can be expressed accurately in logical treatises, but often utilizes language drawn from philosophy, theology, myth, and poetry to express its truths. Do keep in mind that Gnosticism is both an umbrella term encompassing diverse mystical teachings, indicating a way of being philosophic-religious, and is a more specific collective of early Christian sects—there is great overlap between Christian Gnosticism and everything else referred to as Gnostic, but one should not presume a perfect equation between them all.

Gnosis: spiritual knowledge

Pistis: faith

Alchemy:

From the Greek chemeia (the art of metal-working), the Arabic al-kimia, and Latin alchimia. Alchemy was said to have been born over 2000 years before the common era in ancient Egypt and Babylonia but our record mainly speaks of antiquity around 600 years before the common era seeing its creation independently in China, India, and Greece (then spreading from Hellenistic (Greco-Roman) Egypt through the Islamic world to medieval Europe) in both mythical and scholarly practices. Alexandria, in particular, became its locus in the 8-9th c., wherein Pythagoreanism, Neoplatonism, Stoicism, and Gnosticism mixed with Aristotelian ideas; the 12th c. saw its revival with the translation of Arabic works into Latin). Medieval alchemy was scientific, philosophic, and mystical; its concerns were holistic, demanding a purity of mind, body, and spirit. Its principle belief is that all matter is composed of four elements (earth, air, fire, and water), and the right mixture of elements permitted the creation of any substance through a transmutation of one substance to another. Some alchemical practice was aimed at curing disease (and advancement of all medical sciences; notably Paracelsus), some at prolonging life (finding the “Philosopher’s Stone”), some at creation of life, some at practical transmutation, such as the cliché of “turning lead into gold.”

- Philosopher’s Stone: lapis philosophorum; the central symbol and goal of most alchemy (it gives us the phrase Magnum opus, the Great Work), it was a substance said to be able to turn base metals into gold or silver and be an elixir of life, rejuvenating and granting immortality (powers also attributed to it: reviving dead plants, creating flexible glass, turning crystals into diamonds, creating forever-burning lamps, and the creation of a golem). Its existence was assumed to be both or either literal or allegorical, the latter making it a symbol of enlightenment. Its first known mention is in Zosimos of Panopolis’ (ca. 300 c.e.) Cheirokmeta, although many alchemists look to Plato’s Timaeus as its source, Christian alchemical writers attributed its origin back to Adam (who acquired the knowledge directly from God), Jewish alchemists to Solomon, etc.. Legend has it that the 13th c. philosopher Albertus Magnus discovered the stone and left it, at his death, to his student Aquinas (Magnus’ writings note his witnessing the creation of gold by transmutation). A 17th c. mystical “text,” Mutus Liber, the “wordless text,” contained only 15 illustrations said to be a symbolic manual for creating the philosopher’s stone.

|

Links to more on the Philosopher's Stone & Alchemy:

|

Alchemy had exoteric, practical applications and esoteric, theoretical applications. It began the study of chemistry, and identified elements and chemicals used today, including arsenic, bismuth, hydrochloric acid, nitric acid, potash, sodium carbonate, gun powder (Roger Bacon was the first European to describe the process), etc., as well as laboratory devices and practices (such as the extraction of metals from ore) still in use (Isaac Newton’s theory of gravity was said to have been inspired by his alchemical studies). Alchemy also inspired aesthetics, due to its reliance on symbols, and it was also a theological study; Saint Aquinas studied alchemy before it was deemed heretical by the Church, Pope Clement IV and Pope Innocent VIII supported its study, and Martin Luther deemed it beneficial for and consistent with Christian teachings.

Theoretically, alchemy’s idea of turning one substance into another, for example, lead into gold, was thought to have a parallel to transforming oneself, that is, purifying oneself into a more perfect form. The alchemical mission became an analogy for spiritual exercise. For the relation to Al-Ghazali, keep in mind this relation of transmutation as a purification to a more perfect state; for the relation of this and Al-Ghazali to earlier readings in the course, keep in mind Boethius’ Lady Philosophy as a doctor who was to cure him of his disease of sickly anxiety and Augustine’s references to God as the Divine Physician whose contemplation and grace cured his sickly, sinful soul and troubled, confused mind. The transformation is a purification and a remedying of sickliness.

Al-Ghazzali's Alchemy of Happiness

Al-Ghazzali's Alchemy of Happiness

(II) Textual Analysis:

Al-Ghazzali’s On Knowing Yourself and God, a translation of his Alchemy of Happiness, from the Persian, by Muhammad Nur Abdus Salam (Chicago: Great Books of the Islamic World, KAZI Publications, Inc., 2002).

Divided into two parts: On Knowing Yourself (pp.7-40) and On Knowing God (pp.41-64).

(II) Textual Analysis:

Al-Ghazzali’s On Knowing Yourself and God, a translation of his Alchemy of Happiness, from the Persian, by Muhammad Nur Abdus Salam (Chicago: Great Books of the Islamic World, KAZI Publications, Inc., 2002).

Divided into two parts: On Knowing Yourself (pp.7-40) and On Knowing God (pp.41-64).

(Part One) On Knowing Yourself (pp.7-40)

“Know that the key to the knowledge of God, may He be honored and glorified, is knowledge of one’s own self,” the text begins, telling us immediately the content herein and the central mission of his work and the faithful’s (7). There is nothing more intimate to oneself than oneself, he tells us, and without knowing oneself, how could anyone know anything else? But, we discover, few truly know themselves, hence the need for this guide. We must learn to look beyond the body and animalistic impulses, and seek the essential truth of the self that he designates as embodying the knowledge of the questions: “What sort of a thing are you? Where did you come from? Where are you going? Why have you come to this stopping place? For what purpose were you created? What is your happiness and in what does it lie? What is your misery and in what does that lie?” (7). These last two questions are the key here. Strongly reminiscent of Aristotle’s Ethics and Plato’s dialogues, we have a brief treatise of numbered and titled sections that identify our greatest good as “happiness,” in the Abrahamic tradition of this being Godliness and/or God, and the “alchemical” part being the process of how to achieve it through delineations of parts of the self/soul. Hence, the work’s original title, Alchemy of Happiness.

The self is composed of many attributes, which he describes using numerous metaphors and analogies throughout (keep in mind the mystical tradition of esoteric, spiritual knowledge needing its conveyance through poetic language and indirection). These attributes are first presented to us those of beasts of burden, those of predatory animals, those of demons, and those of the angels.

The attributes of the beasts of burden find their nourishment and happiness in eating, sleeping, and copulating. Those of predatory animals find their nourishment and happiness in tearing apart, killing, and rage. Those of demons find their nourishment and happiness in encouraging evil treachery, and deceit. And those of the angels find their nourishment and happiness in the contemplation of the Divine Presence. Al-Ghazali is schooling us to discover of what nature we have, which of these attributes controls us. The last, the angelic, is obviously our ideal and goal. To be this sort of being, we must liberate ourselves from the “grip of anger and lust” and “strive to come to know the Divine Presence and open yourself to the contemplation of Its Beauty” (8).

We must understand all of these attributes within us and strive to have them all working for good and under the control by the good. “When you have obtained that seed of happiness, place those (those tools) underfoot and turn your face to the resting place of your own (spiritual) happiness, that resting place for which the elite expression is the Divine Presence and for which the common expression is ‘Paradise’” (8). This, then, is the goal; to achieve it, we must learn about the self.

The text continues to school us in the Outer Form and the Inner Spirit, which is called Heart, how the Heart rules over the outer, bodily forms, where good and bad come from, how to guard ourselves against the latter, more about the Heart and its connection to Heaven, how this goodness is innate within us all, how to exercise it through power, and then about the nature of prophets and saints. This leads to a description of how the way to these states is veiled and the knowledge that is required to achieve it. This knowledge is intellectual (in the sense of gnostic, spiritual knowledge) and concerns the bodily, invoking long explications of anatomy, and ending in an explanation of our weakness and the imperfection in the world.

On knowing yourself: this is key to knowing God; this leads to happiness …

Knowledge of God via knowledge of his handiwork, all of creation (cf p.12); the heart’s work is to seek happiness. Happiness found in gnosis of God. Alchemical part is to become happy via knowing, which inspires and requires purification (cf p.32).

outline of part one: On Knowing Yourself

closer textual analysis

Introductory passage: On Attributes: (pp.7-8)

Sec. 1 (p.9)

Outer Form: seen by eye, visible world: flesh is tool for heart, limbs are soldiers of heart.

Inner Form: aka: nafs, soul; jan, vital principle; dil, heart; seen by inner vision; stranger and wayfarer to this world; monarch of the body.

Sec. 2 (10)

Must first know that it (the heart) is, then what it is –recognize existence then its nature. Then come to know specifics, i.e., number of its armies (the bodily aspects it controls, the acts it can do). Then come to know its relationship to those armies. Then come to know its character, i.e., how it attains knowledge of God and its own spiritual happiness.

Sec. 3 (10-12)

World of Creation: affected by measurement, the visible world.

World of Command: the human spirit. Spirit has no amount or quantity, thus cannot be divided. But, this spirit is created; it is of both worlds, created and creating, or of the latter world of command.

But, a bit unclear what indivisible means here, is he adopting the Aristotelian or Platonic tripartite soul? Sounds as if, given the attributes (pp.7-8)… cleared up below …

Spirit is not pre-existence (Anti-Plato); it is not accidental (Aristotle).

Thus … vital principle cannot be divided, but there is within us the “animating spirit,” which is divisible and even possessed by other animals. “Heart” (vital principle, essence) had only by humans.

Note the next information: “[This gnosis (marifat)] is not needed at the beginning for travelling the way of religion. The beginning of the way of religion is, rather, the greater struggle (mujahadat). If a person makes this greater struggle a prerequisite, this gnosis will come to him of itself, without hearing it from anyone else” (11).

He concludes the section with a reminder that this is esoteric knowledge, not intended for the uninitiated, those who have not gone through the greater struggle.

Sec. 4 (12-13)

The work of the heart is to seek happiness.

Happiness is in the gnosis of God.

It attains this knowledge of God through knowing His handiwork, all of creation.

Body described as army for heart.

Has external army, hands, feet, stomach, etc.

Has internal army, appetite, lust, anger.

Has senses, which are internal and external.

All these armies at command of the heart.

Sec. 5 (13-14)

Metaphor of body as a nation and limbs and organs are its workers.

Sec. 6 (14-15) Sovereignty of the heart

Lust and anger created for the nourishment and preservation of the body; they are servants to the body; food and drink are the fodder for the body.

Body created to bear the senses; senses created for intelligence to gather information. They serve as net to catch information so as to know the handiwork of God, by which we know God. Senses are servants to reason. Reason is servant to the heart.

The heart must not kill any rebels, because they are all needed, but must seek to bring them under his proper control.

Sec. 7 (15-17)

There is a connection between all of the armies and the heart. Good and bad qualities come from these armies. The qualities can be grouped into four types (attributes described pp.7-8):

Can describe these as:

Sec. 8 (17-19)

Must guard oneself against bad qualities. “Recognize truly that from every move you make, a trait is acquired by the heart which remains with you and accompanies you to (the next) world” (17). These traits: morals. They come from these four qualities.

“The heart is like a bright mirror; repugnant traits are like smoke and darkness which, when they touch it, darken it so that tomorrow one will not see the Divine Presence and it will become veiled (to one’s view). Good traits are the light which reaches the heart and wipes away the darkness of sin” (18).

--note connection to Augustine, Marguerite Porete, Marguerite d’Oignt, etc. “mirror”

Sec. 9 (19-20)

We have these qualitites, but at origin, we are created with the essence of angels. The perfection within us is the highest quality and the reason for which we have been created.

His example: horse is more noble than donkey … it can carry, like donkey, but made for running, warfare, etc., the increased perfections over the donkey.

We were not created for mere animal, base acts (eating, sleeping, copulating), and look at how creatures can do these things better than us (camels eat more, sparrows reproduce more). We are superior to them in matters of having heart.

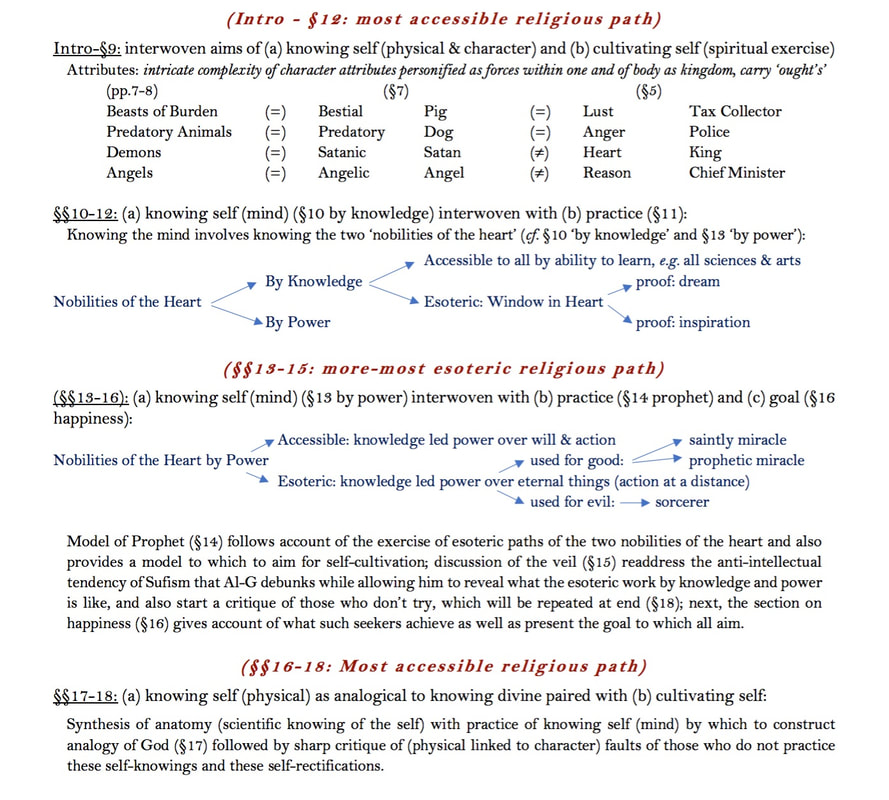

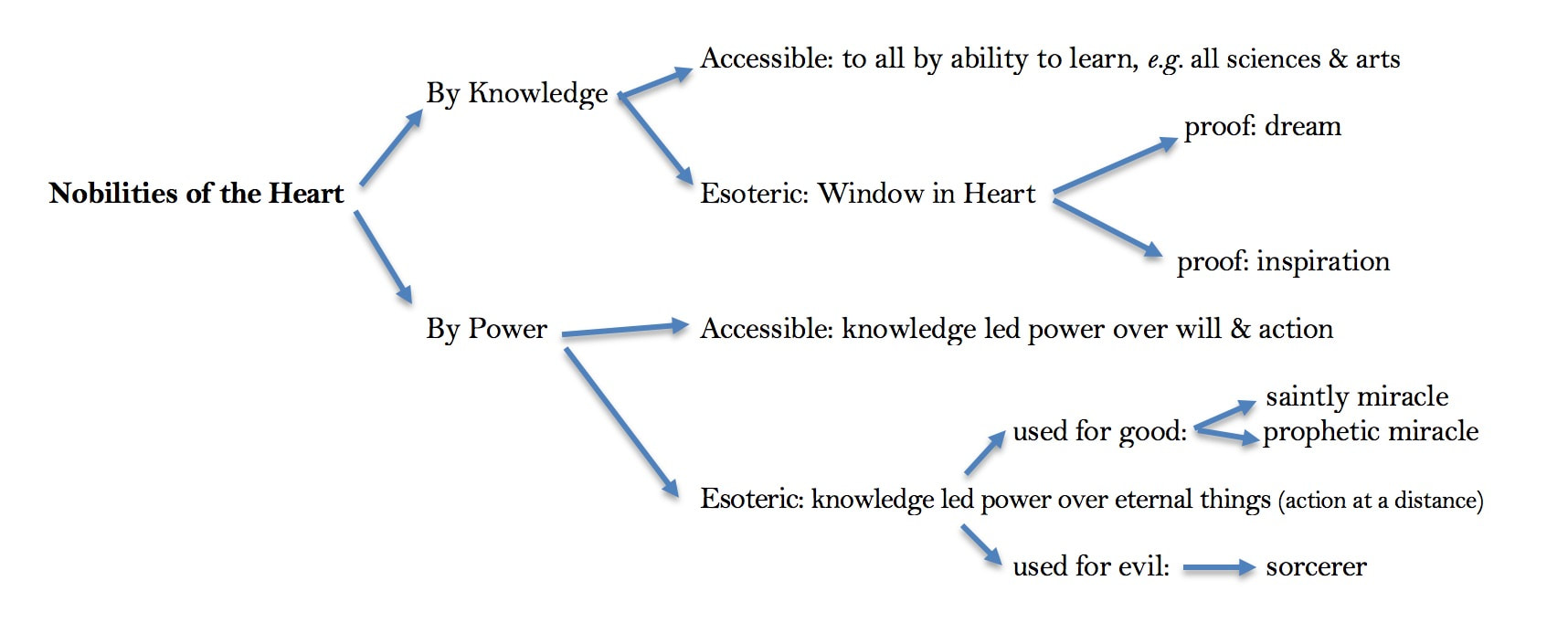

Image: Schema for §§10-13:

- Beasts of Burden

- Predatory Animals

- Demons

- Angels

Sec. 1 (p.9)

Outer Form: seen by eye, visible world: flesh is tool for heart, limbs are soldiers of heart.

Inner Form: aka: nafs, soul; jan, vital principle; dil, heart; seen by inner vision; stranger and wayfarer to this world; monarch of the body.

- Attributes: knowledge of God; witnessing beauty of Divine Presence.

- Burden of Duty: addressed, chastised, punished.

- Real source and final return: Divine Presence.

- Know the inner form and one has the key to knowing God.

Sec. 2 (10)

Must first know that it (the heart) is, then what it is –recognize existence then its nature. Then come to know specifics, i.e., number of its armies (the bodily aspects it controls, the acts it can do). Then come to know its relationship to those armies. Then come to know its character, i.e., how it attains knowledge of God and its own spiritual happiness.

Sec. 3 (10-12)

World of Creation: affected by measurement, the visible world.

World of Command: the human spirit. Spirit has no amount or quantity, thus cannot be divided. But, this spirit is created; it is of both worlds, created and creating, or of the latter world of command.

But, a bit unclear what indivisible means here, is he adopting the Aristotelian or Platonic tripartite soul? Sounds as if, given the attributes (pp.7-8)… cleared up below …

Spirit is not pre-existence (Anti-Plato); it is not accidental (Aristotle).

Thus … vital principle cannot be divided, but there is within us the “animating spirit,” which is divisible and even possessed by other animals. “Heart” (vital principle, essence) had only by humans.

Note the next information: “[This gnosis (marifat)] is not needed at the beginning for travelling the way of religion. The beginning of the way of religion is, rather, the greater struggle (mujahadat). If a person makes this greater struggle a prerequisite, this gnosis will come to him of itself, without hearing it from anyone else” (11).

He concludes the section with a reminder that this is esoteric knowledge, not intended for the uninitiated, those who have not gone through the greater struggle.

Sec. 4 (12-13)

The work of the heart is to seek happiness.

Happiness is in the gnosis of God.

It attains this knowledge of God through knowing His handiwork, all of creation.

Body described as army for heart.

Has external army, hands, feet, stomach, etc.

Has internal army, appetite, lust, anger.

Has senses, which are internal and external.

- Internal: imagination, thought, memory, recall, conjecture

- External: nose, eyes, ears, taste, touch

All these armies at command of the heart.

Sec. 5 (13-14)

Metaphor of body as a nation and limbs and organs are its workers.

- Lust: tax collector

- Anger: policeman

- Heart: King

- Reason: King’s chief minister

Sec. 6 (14-15) Sovereignty of the heart

Lust and anger created for the nourishment and preservation of the body; they are servants to the body; food and drink are the fodder for the body.

Body created to bear the senses; senses created for intelligence to gather information. They serve as net to catch information so as to know the handiwork of God, by which we know God. Senses are servants to reason. Reason is servant to the heart.

The heart must not kill any rebels, because they are all needed, but must seek to bring them under his proper control.

Sec. 7 (15-17)

There is a connection between all of the armies and the heart. Good and bad qualities come from these armies. The qualities can be grouped into four types (attributes described pp.7-8):

Can describe these as:

- Bestial, dog

- Predatory, pig

- Satanic, Satan

- Angelic. Angel

Sec. 8 (17-19)

Must guard oneself against bad qualities. “Recognize truly that from every move you make, a trait is acquired by the heart which remains with you and accompanies you to (the next) world” (17). These traits: morals. They come from these four qualities.

“The heart is like a bright mirror; repugnant traits are like smoke and darkness which, when they touch it, darken it so that tomorrow one will not see the Divine Presence and it will become veiled (to one’s view). Good traits are the light which reaches the heart and wipes away the darkness of sin” (18).

--note connection to Augustine, Marguerite Porete, Marguerite d’Oignt, etc. “mirror”

Sec. 9 (19-20)

We have these qualitites, but at origin, we are created with the essence of angels. The perfection within us is the highest quality and the reason for which we have been created.

His example: horse is more noble than donkey … it can carry, like donkey, but made for running, warfare, etc., the increased perfections over the donkey.

We were not created for mere animal, base acts (eating, sleeping, copulating), and look at how creatures can do these things better than us (camels eat more, sparrows reproduce more). We are superior to them in matters of having heart.

Image: Schema for §§10-13:

Sec. 10 (21-23)

Marvels of the worlds of the heart:

Heart’s nobility has two degrees:

One by way of knowledge, (knowable by masses) –ability to learn all things.

Other by way of power, (knowable by some) --‘window’ in heart that opens to kingdom of heaven … can know this two ways:

Sec. 11 (23-4)

This window to heaven is not only accessible in death and sleep – we can also strive to see through it in our waking life.

We do this by practicing spiritual discipline … remove the heart beyond grip of anger, lust, ill nature, and all necessities of this world. Sit in secluded place, recite the names of God with the heart, and the heavens will be shown to you.

To do this, must cut oneself off from the world and give oneself to God. This is instruction in spiritual practice and is the way of saints, the way of prophet-hood.

The other way is acquiring knowledge by academic learning. This too is great, he says, but is trivial in comparison to spiritual learning (taken in by the hearts from the prophets).

Sec. 12 (24-6)

Innate nature in all … knowledge of divine in all … note openness.

Sec. 13 (26-7)

Nobility by power … not shared by animals, but unique to humans. All have this power to control their own selves, but some have this power that controls others around him/her (e.g., his awe will affect a lion, who will become tame to him). We have evidence of this in everyday world, e.g., evil eye, sorcery, miracles, etc. Al-Ghazali affirms these are real.

Marvels of the worlds of the heart:

Heart’s nobility has two degrees:

One by way of knowledge, (knowable by masses) –ability to learn all things.

Other by way of power, (knowable by some) --‘window’ in heart that opens to kingdom of heaven … can know this two ways:

- By dreaming, sleep not en cumbered with sensory intake from physical world (and another reference to mirrors);

- Inner voice of inspiration, don’t know where it comes from, but not from perception or senses.

Sec. 11 (23-4)

This window to heaven is not only accessible in death and sleep – we can also strive to see through it in our waking life.

We do this by practicing spiritual discipline … remove the heart beyond grip of anger, lust, ill nature, and all necessities of this world. Sit in secluded place, recite the names of God with the heart, and the heavens will be shown to you.

To do this, must cut oneself off from the world and give oneself to God. This is instruction in spiritual practice and is the way of saints, the way of prophet-hood.

The other way is acquiring knowledge by academic learning. This too is great, he says, but is trivial in comparison to spiritual learning (taken in by the hearts from the prophets).

Sec. 12 (24-6)

Innate nature in all … knowledge of divine in all … note openness.

Sec. 13 (26-7)

Nobility by power … not shared by animals, but unique to humans. All have this power to control their own selves, but some have this power that controls others around him/her (e.g., his awe will affect a lion, who will become tame to him). We have evidence of this in everyday world, e.g., evil eye, sorcery, miracles, etc. Al-Ghazali affirms these are real.

(Part Two) On Knowing God (pp.41-64).

The theoretical crux of this second part is his initial revelation of the spiritual knowledge of the self is the key to the spiritual knowledge of God. He cites the common prophetic saying: “He who knows himself knows his Lord” (41)—this knowing is “obligatory” (41). This self knowledge is named a “mirror of gnosis” (41), and has two parts, an esoteric meaning that the masses cannot grasp, and a simple meaning, all can grasp and use to glorify the Lord (§1).

This simple knowing is encompassed in using self-knowledge as an analogical tool to know God’s attributes, but not in a literal sense, thinking his form is like our form, but beginning with the recognition of the perfection of the design of the body as fulfillment of its function. For example, considering all of our attributes and every part of the body fulfilling its many different functions, we understand the perfection of the Creator’s knowledge (e.g., we are a multi-faceted, complex creation perfectly designed in all our many, many details). He cites the example of how perfectly our hands are designed to do so many different activities and how no other design of a hand could be better (43). Thus, in this way, we see all of the different aspects of God’s perfection: perfect knowledge, design/creation, power, goodness, etc.

Recognizing these perfections is an act of self-purification (stand in awe and respect for selves and desire to be the best we can be) and an act of glorifying God (§2: pp.44-6). But, of course, God’s perfection and His essence surpasses what we can know of Him. However, even the ineffable and inscrutable knowledge of God can be grasped (that there is such) by contemplation of our own selves (45). For example, “if a person were to seek the true nature of sound, … of smell, … of taste their nature and quality—he will be incapable of doing so” (45) because our knowledge of these things comes through our senses, and each sense controls different provinces (e.g., the eye sees, it does not hear), thus our knowledge is compositions of facets received through mediums, transmitted to other faculties, etc.

Thus, through analogy, knowledge of the self can tell us about knowledge of God and of what we cannot have knowledge. “The point is that a person can come to know the ineffability and inscrutability of himself from the ineffability and inscrutability of God …” (46). These levels of the unknowable that are knowable through circular analogy (use analogy from us to Him and from Him to us) about God concern His essence, His attributes, and also His rule or management of His kingdom. This, too, we know by analogy of how we rule and are ruled in everyday life (46-51). (Why? Because “Verily God Most High created man in His image” (46)—remember emanation theory: all that is is in God before it is in being, and there is nothing in being that is not of and from God).

So, how do we know God’s management of His kingdom (§3)? How does he rule? This is called the “gnosis of the Acts,” and is also known through self-examination and analogical thinking. Thus, we must examine how we know our acts.

From here, the text turns to a critique of those who misunderstand Divine gnosis. The first attack comes as a comparison of the naturalist and astrologer to ants (51-3), followed by a section on why there are disputes on truth amongst people (53-4). The next comparison is the likeness of stars and the signs of the zodiac to a royal establishment (54-6).

This is followed by an explication of the four glorifications of God (“Glory be to God,” “Praise be to God,” “there is no god but God,” and “God is greater”) (56-7). These 'glorifications' are frequently called Al-Tasbihat al-Arba'a or shortened to Tasbih, a practice of Dhikr consisting of the repetition of short sayings that glorify God--although Tasbih is also used specifically as a name of the first (Glory be to God), alongside Tahmid (praise be to God), Tawhid (God is one, or there is no god but God), and Takbir (God is greater). They are used to promote one's God-wariness, attuning oneself to contemplation of the divine. For Al-Ghazzali, these glorifications are condensations of all the gnosis of God. This is followed by a warning to follow religious law in the purification of the self.

Then, he ends on a return to a critique, now against the libertines and their seven ignorances that lead them to violate God’s will. To correct these violations, like one who is ill, one must first diagnose the ignorance within oneself that has led to the violation and cure this ill.

Misc. Other Outside Resources:

The theoretical crux of this second part is his initial revelation of the spiritual knowledge of the self is the key to the spiritual knowledge of God. He cites the common prophetic saying: “He who knows himself knows his Lord” (41)—this knowing is “obligatory” (41). This self knowledge is named a “mirror of gnosis” (41), and has two parts, an esoteric meaning that the masses cannot grasp, and a simple meaning, all can grasp and use to glorify the Lord (§1).

- --On the “mirror,” cf., pp. 18, 22.

This simple knowing is encompassed in using self-knowledge as an analogical tool to know God’s attributes, but not in a literal sense, thinking his form is like our form, but beginning with the recognition of the perfection of the design of the body as fulfillment of its function. For example, considering all of our attributes and every part of the body fulfilling its many different functions, we understand the perfection of the Creator’s knowledge (e.g., we are a multi-faceted, complex creation perfectly designed in all our many, many details). He cites the example of how perfectly our hands are designed to do so many different activities and how no other design of a hand could be better (43). Thus, in this way, we see all of the different aspects of God’s perfection: perfect knowledge, design/creation, power, goodness, etc.

- --We know that our essence comes from our existence, thereby we know analogically that God’s essence exists.

- --We exist; we know that before we existed, we were non-existent; we know we cannot create even a hair, hence we know we did not create ourselves; we know, then we have a creator; hence we know the essence of God as creator (41-2).

- --We know by our own attributes, analogically, the attributes of God.

- --Considering ourselves internally, we understand our attributes … (see below).

- --We know by our own self-control of our bodies, analogically, the control God exercises over the whole world.

- --Considering ourselves internally and externally, we see the power of our creator.

- --Considering further, we see that each attribute and limb was created for a purpose; seeing purpose, we see the perfection of our creator.

- --Considering, for example, the hands, we see their perfection, hence we see “that the knowledge of the Creator encompasses this person and He is aware of everything. Thus, there is wisdom in each part of a person” (43).

- --When we see our own needs (for food, clothing, shelter, etc.), we see the grace and mercy of the Creator (hence, some of His attributes) (§1).

- --Further attributes we can know: His incomparability and Sanctity by our own purity and sanctity (§2)—hence, to know this, we must become it, hence …

Recognizing these perfections is an act of self-purification (stand in awe and respect for selves and desire to be the best we can be) and an act of glorifying God (§2: pp.44-6). But, of course, God’s perfection and His essence surpasses what we can know of Him. However, even the ineffable and inscrutable knowledge of God can be grasped (that there is such) by contemplation of our own selves (45). For example, “if a person were to seek the true nature of sound, … of smell, … of taste their nature and quality—he will be incapable of doing so” (45) because our knowledge of these things comes through our senses, and each sense controls different provinces (e.g., the eye sees, it does not hear), thus our knowledge is compositions of facets received through mediums, transmitted to other faculties, etc.

Thus, through analogy, knowledge of the self can tell us about knowledge of God and of what we cannot have knowledge. “The point is that a person can come to know the ineffability and inscrutability of himself from the ineffability and inscrutability of God …” (46). These levels of the unknowable that are knowable through circular analogy (use analogy from us to Him and from Him to us) about God concern His essence, His attributes, and also His rule or management of His kingdom. This, too, we know by analogy of how we rule and are ruled in everyday life (46-51). (Why? Because “Verily God Most High created man in His image” (46)—remember emanation theory: all that is is in God before it is in being, and there is nothing in being that is not of and from God).

So, how do we know God’s management of His kingdom (§3)? How does he rule? This is called the “gnosis of the Acts,” and is also known through self-examination and analogical thinking. Thus, we must examine how we know our acts.

- --Writing: Desire and will surface in heart to write; motion and movement occurs in heart; motion as “tenuous substance” called spirit travels to brain; content of writing appears as an image before the brain (from imagination); this result is transferred to the nerves; nerves activate the fingers; fingers move the pen; pen moves the ink; the writing appears on paper (47-8). The initiator of this writing is desire.

- --Likewise (analogically) with God: first effect of His will appears on the Throne, then goes other places; God’s “spirit,” which moves the desired will, is the angel, spirit, or Holy Spirit; the form first appears on “the Preserved Tablet” (cf. 21-2, 49--see selection at very end on Preserved Tablet from another Al-G text); then to the four temperaments (hot, cold, moist, dry); then these move (like the pen moves ink) the elements of the compounds; then there is creation and rule (48-9).

From here, the text turns to a critique of those who misunderstand Divine gnosis. The first attack comes as a comparison of the naturalist and astrologer to ants (51-3), followed by a section on why there are disputes on truth amongst people (53-4). The next comparison is the likeness of stars and the signs of the zodiac to a royal establishment (54-6).

- See <~here~> for a wikipedia article on the blind men and elephant tale (re: §6)

- See <~here~> for an article on Islamic astrology, astronomy, and zodiac in art from The Met (re: §7)

- See <~here~> for a brief article overview on cosmology in Sufism, Hermeticism, and Islam (re: §7)

- And <~here~> for an article on Ibn Arabi's comparable use of astrology (re: §7)

This is followed by an explication of the four glorifications of God (“Glory be to God,” “Praise be to God,” “there is no god but God,” and “God is greater”) (56-7). These 'glorifications' are frequently called Al-Tasbihat al-Arba'a or shortened to Tasbih, a practice of Dhikr consisting of the repetition of short sayings that glorify God--although Tasbih is also used specifically as a name of the first (Glory be to God), alongside Tahmid (praise be to God), Tawhid (God is one, or there is no god but God), and Takbir (God is greater). They are used to promote one's God-wariness, attuning oneself to contemplation of the divine. For Al-Ghazzali, these glorifications are condensations of all the gnosis of God. This is followed by a warning to follow religious law in the purification of the self.

- See <~here~> for a wikipedia overview of Tasbih;

- See <~here~> for another brief encyclopedia overview of Al-Tasbihat al-Arba'a;

- See <~here~> for a commentary on the prayer.

Then, he ends on a return to a critique, now against the libertines and their seven ignorances that lead them to violate God’s will. To correct these violations, like one who is ill, one must first diagnose the ignorance within oneself that has led to the violation and cure this ill.

- --Notice the increasing severity! To the point of: “Therefore, dealing with such people [the seventh form of ignorance: lust] is done better by the sword than by the argument of reason” (64). Hence, we see that some can have doubts in speech and be corrected—in fact, these, we ought to correct; but, some can have doubts from other sources and not be corrects, and these we ought to kill.

Misc. Other Outside Resources:

Al-Ghazzali's

THE PEN AND THE PRESERVED TABLET (LAWH AL-MAHFUZ)

"It has been possible to conceive of the existence of the Seven Heavens and Paradise and Hell all written on a small “Preserved Tablet” or a small piece of paper and preserved in a minute part of the heart and seen with a part of the eyeball, not exceeding the size of a lentil seed, without the Heavens and Earth, Paradise and Hell actually existing in the eyeball or the heart or the tablet or the paper. It is not necessary that the pen and the tablet should be the same, as we know, for they are formless and only God can know what they really are. In spite of our selfless efforts, we miserably fail to imagine the feature of God’s fingers with which He writes on the “Preserved Tablet”. We also fail to understand how the tablet receives impressions like a hard and broad body upon which writing is inscribed, as children write upon a slate. For the multiplicity of this writing requires something extended on which to write. And if the writing is infinite, the material bearing it will be likewise infinite. Apparently, infinite body and infinite lines on a single body are inconceivable. It is also possible to conceive of the speech of God as being read with tongues preserved in the hearts and written in books without the actual existence of that speech in these things. For if the very speech of God should actually exist on the leaves of a book, God Himself, through the writing of His name on these leaves, would exist actually thereon. Similarly, the very fire of Hell, through the writing of His name on the leaves, would exist actually thereon and the leaves would be consumed. In like manner God is seated upon the throne in the sense which He willed by that state of equilibrium - a state which is not inconsistent with the quality of grandeur to which the symptoms of origination and annihilation do not permeate. If these things cannot be explained in terms of the power of a powerful being, how then can they be explained at all? It is essential, therefore, that we should believe in them in accordance with religion. As a result of the deep search into the problem of essence and attributes, it has been found that God is the only reality; we are but phenomenal. Human attributes are only impressions and ephemeral mirroring faintly God’s attributes which are eternal. Whatever the mind conceives is definite in so far as it is limited by place and time, but God is not a space-filling body and His life is timeless. The difference between God’s knowledge and power and human knowledge and power is greater than the difference between any two things, for He is not composed of bodies within whose limits powers are diffused. His power and will and knowledge are one and the same as His essence. His life is not like ours, which needs for its completion the two different powers which are manifested through our knowledge and action. On the contrary, His life is identical with His essence. If His attributes are attributed to us, we would not understand them. Death is the separation of soul from the body, which is reunited at the command of God on the Day of Resurrection"

--Al-Ghazzali, The Mysteries of the Human Soul (AL-MADNUN BIHI `ALA GHAIR AHLIHI), Ch.III, available <~here~>.

THE PEN AND THE PRESERVED TABLET (LAWH AL-MAHFUZ)

"It has been possible to conceive of the existence of the Seven Heavens and Paradise and Hell all written on a small “Preserved Tablet” or a small piece of paper and preserved in a minute part of the heart and seen with a part of the eyeball, not exceeding the size of a lentil seed, without the Heavens and Earth, Paradise and Hell actually existing in the eyeball or the heart or the tablet or the paper. It is not necessary that the pen and the tablet should be the same, as we know, for they are formless and only God can know what they really are. In spite of our selfless efforts, we miserably fail to imagine the feature of God’s fingers with which He writes on the “Preserved Tablet”. We also fail to understand how the tablet receives impressions like a hard and broad body upon which writing is inscribed, as children write upon a slate. For the multiplicity of this writing requires something extended on which to write. And if the writing is infinite, the material bearing it will be likewise infinite. Apparently, infinite body and infinite lines on a single body are inconceivable. It is also possible to conceive of the speech of God as being read with tongues preserved in the hearts and written in books without the actual existence of that speech in these things. For if the very speech of God should actually exist on the leaves of a book, God Himself, through the writing of His name on these leaves, would exist actually thereon. Similarly, the very fire of Hell, through the writing of His name on the leaves, would exist actually thereon and the leaves would be consumed. In like manner God is seated upon the throne in the sense which He willed by that state of equilibrium - a state which is not inconsistent with the quality of grandeur to which the symptoms of origination and annihilation do not permeate. If these things cannot be explained in terms of the power of a powerful being, how then can they be explained at all? It is essential, therefore, that we should believe in them in accordance with religion. As a result of the deep search into the problem of essence and attributes, it has been found that God is the only reality; we are but phenomenal. Human attributes are only impressions and ephemeral mirroring faintly God’s attributes which are eternal. Whatever the mind conceives is definite in so far as it is limited by place and time, but God is not a space-filling body and His life is timeless. The difference between God’s knowledge and power and human knowledge and power is greater than the difference between any two things, for He is not composed of bodies within whose limits powers are diffused. His power and will and knowledge are one and the same as His essence. His life is not like ours, which needs for its completion the two different powers which are manifested through our knowledge and action. On the contrary, His life is identical with His essence. If His attributes are attributed to us, we would not understand them. Death is the separation of soul from the body, which is reunited at the command of God on the Day of Resurrection"

--Al-Ghazzali, The Mysteries of the Human Soul (AL-MADNUN BIHI `ALA GHAIR AHLIHI), Ch.III, available <~here~>.

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by MacHighway